The fading beams of my flashlight sweep the cavernous reinforced concrete laterals of Malinta Tunnel, barely illuminating my passage. Vintage wires and fixtures, timber trusses, and piles of rubble flare into focus in fleeting camera flashes, then vanish, frustratingly, in the blackness. Nevertheless, it’s an enlightening moment: I realize that seeing Corregidor, the tadpole-shaped bastion of crumbling bunkers and silent seacoast guns on which roughly 15,000 besieged American and Filipino troops weathered the worst of the early Pacific War, is literally only half the battle. One must enlist all the senses, not to mention the imagination, to experience—to truly feel—what war was like on the famed fortress island.

The fading beams of my flashlight sweep the cavernous reinforced concrete laterals of Malinta Tunnel, barely illuminating my passage. Vintage wires and fixtures, timber trusses, and piles of rubble flare into focus in fleeting camera flashes, then vanish, frustratingly, in the blackness. Nevertheless, it’s an enlightening moment: I realize that seeing Corregidor, the tadpole-shaped bastion of crumbling bunkers and silent seacoast guns on which roughly 15,000 besieged American and Filipino troops weathered the worst of the early Pacific War, is literally only half the battle. One must enlist all the senses, not to mention the imagination, to experience—to truly feel—what war was like on the famed fortress island.

Especially inside Malinta Tunnel. Blasted and bored deep into the island by U.S. Army engineers, the bombproof 830-foot tunnel was the inner command sanctum of the United States Army Forces, Far East; its 400-foot ventilated shafts were hospital wards and stores of food, fuel, and ammunition (see “Hard Time on the Rock,” May/June 2012). The laterals now serve as subterranean wormholes to the desperate days in early 1942 when Japanese bomb and shell concussions rocked these recesses in mad, seismic, light-flickering tremors. I imagine the stinging odors of gasoline and gangrenous flesh, the din of diesel generators and of jeeps and ambulances growling through the overcrowded main corridor.

A more subtle historic echo in the eerie tunnels is the tapping of trans-Pacific radio transmissions. It was from one of these laterals that perhaps the most poignant message in U.S. military history originated. In his final broadcast to the president, General Jonathan M. Wainwright, commander of Allied forces in the Philippines, radioed: “With broken heart and head bowed in sadness, but not in shame, I report that today I must arrange terms for the surrender…. Please say to the nation that my troops and I have accomplished all that is humanly possible and that we have upheld the best tradition of the United States and its army. With profound regret and with continued pride in my gallant troops, I go to meet the Japanese commander.”

As I exit through giant black vault doors, the blinding tropical sunlight reveals that Corregidor itself has yet to surrender—thanks to the stewardship of the Corregidor Foundation and the six-square-mile island’s roughly 175 inhabitants, most of whom are seasonal workers. Corregidor is the best-preserved battlefield of the Pacific, if not the entire war. Incredibly, it even has a contemporary American “garrison,” albeit a small one: Steve and Marcia Kwiecinski.

The son of a U.S. Army veteran who fought and was captured on Corregidor, Steve Kwiecinski was well-versed in the island’s lore but unprepared for the emotions stirred by his first visit in May 2002. “I was awestruck and emotionally overpowered,” recalls the retired computer programmer. He returned in 2003 with his wife Marcia, who was similarly affected. By 2008, the couple had sold their Michigan home and set out to fulfill an American dream with an unusual twist: enjoy retirement on a beautiful island paradise that also happens to be a legendary World War II battlefield. Like park rangers in flip-flops, they spend their time exploring, working on preservation and maintenance projects, and guiding tours for visitors ranging from American congressmen, Philippine officials, embassy personnel, foreign dignitaries, and active and retired military personnel, including a dwindling handful of World War II veterans with Corregidor memories.

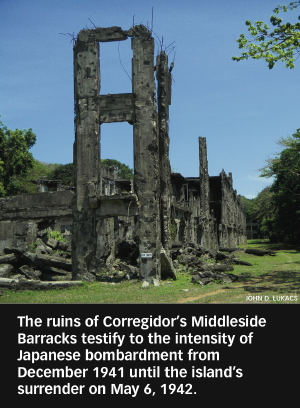

Absorbing Corregidor’s verdant tropical beauty from the passenger seat of the Kwiecinskis’ shiny silver jeep as we head out to explore the rest of the island, I understand the lasting lure—and why American troops affectionately called Corregidor the Rock. Corregidor has three terraces of elevation called Bottomside, Middleside, and Topside; their rugged topography—rocky, shark-patrolled shoreline, jungle-swathed hills, limestone cliffs, and yawning ravines —undoubtedly provided a comforting illusion of impregnability. Our gradual, gear-grinding ascent leads first to the concrete skeleton of the Middleside Barracks, where I join a few goats exploring the decrepit upper floors, then to a succession of stops at the island’s most popular attractions: the batteries.

Corregidor bristles with 20-plus batteries of titanic, turn-of-the-20th-Century fixed coastal guns and mortars, most of which were named for soldiers killed in the 1899 Philippine-American War. While nearly all were rendered obsolete by interwar advances in military technology, they remain impressive and thought-provoking pieces of artillery. At Battery Way, near the ammunition bunkers, a stenciled “silence” in peeling, faded black paint seems unnecessary; mangled steel blast doors and pocked battlements offer mute testimony to the carnage of war. Arriving at Battery Hearn’s monster 12-inch cannon, which could hurl a 1,000-pound armor-piercing shell 17 miles, I take a mental black-and-white snapshot: 70 years earlier, victorious Japanese troops, their arms raised in the “banzai” salute, posed here for a familiar propaganda shot. Next, balancing between weathered stone slabs atop the overgrown gun pits of Battery James, where rapid-fire 3-inch guns once guarded the northern entrance to Manila Bay, I stand astride the past and present as the nuclear-powered super-carrier USS Carl Vinson, fresh from a port visit to Manila, sails past the island.

Located at the mouth of Manila Bay, 30 nautical miles from the teeming Philippine capital, Corregidor is indeed a crowded historical intersection, a stationary, symbolic junction of America’s colonial past, its humiliating early war travails, and its redemptive victory. Nowhere is this more evident than on Topside. The Mile Long Barracks, Post Headquarters, and other structures are shell-scarred façades with staircases to nowhere—all that’s left after brutal bombardments in 1942 and 1945 twice transmogrified the island paradise into a smoking, apocalyptic landscape of craters, charred acacia trees, twisted rebar, and pulverized cement. Standing in the shadow of the movie theater’s shell I survey the parade ground, one of two drop zones for the 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team, charged with retaking the Rock in mid-February 1945. Sea breezes offer relief from the oppressive heat, rustle tall coconut palms, and ripple flags atop the mast of a Spanish warship that sank in the 1898 Battle of Manila Bay, the same flagpole on which the Stars and Stripes was raised following an eloquent speech by General Douglas MacArthur on March 7, 1945, shortly after the island was declared secure.

Set amid these ruins is the Pacific War Memorial. Silhouetted in the distance, against cloudless, powder-blue sky, is a 40-foot rust-hued steel sculpture known as the Eternal Flame of Freedom. Walkways lined with manicured Santa Ana shrubbery direct me to a small museum featuring exhibits of photos, flags, firearms, and Japanese swords, but I am pulled to perhaps the most reflective site on the island. In a rotunda of cool, clean white marble, sun streaming through an oculus in the memorial’s dome illuminates the Altar of Valor and its stirring inscription: “Sleep my sons your duty done, for freedom’s light has come. Sleep in the silent depths of the sea. Or in your bed of hallowed sod. Until you hear at dawn the low clear reveille of God.”

My detour-laden descent proves that on the Rock, roads less traveled are often the most rewarding. It’s not unusual to yield the right of way to a monitor lizard, or catch glimpses of long-tailed macaque monkeys cavorting overhead. The cacophonous calls of seldom-seen cockatoos provide an exotic soundtrack as I tramp to C-1, or Bunker’s Bunker, the command post of Corregidor’s artillery chief Colonel Paul Bunker, and the recently rediscovered ruins of the bungalow that MacArthur and his family occupied on Malinta Hill before evacuating to Australia.

Monsoon rains occasionally reveal rusty relics and ruins concealed by decades of dirt and debris, but the relentless, history-shrouding growth of tropical foliage like bamboo and ipil-ipil presents a never-ending battle fought by island staff with machetes. Most discoveries, though, are made not by slashing, but with the aid of old maps, GPS, and sleuthing. Hibiscus bushes, for example, date to prewar landscaping. “Sometimes,” Marcia Kwiecinski says, “they act as signs alerting us to ruins in the jungle.” Some of Corregidor’s secrets, however, will likely remain undiscovered.

Corregidor’s narrow main thoroughfare snakes to the island’s tapered tail, where waves lap the rocks below the abbreviated grass airstrip of Kindley Field. At nearby Monkey Point, ventilation shafts and caved-in entrances to the Navy Intercept Tunnel offer a tantalizing glimpse of catacombs, just beneath my feet but largely inaccessible. Built to house crypto-intelligence personnel, the tunnel was repurposed into a redoubt by Japanese troops. Their suicidal explosion on February 26, 1945, reportedly knocked men off their feet on the other side of the island and sent rocks crashing onto the deck of a U.S. destroyer anchored more than a mile offshore. With the exception of some tight spaces it’s been sealed ever since.

Fittingly, while waiting for the ferry back to the mainland I’m loitering around the remnants of the South Dock, where many believe that MacArthur famously departed Corregidor via PT boat in March 1942. It’s now little more than pilings—warped concrete and rusted tracks from an old rail system—on the edge of a serene park dotted with radiant red flame trees. Pausing at the base of a towering bronze statue of MacArthur, I give the general a farewell salute and a knowing nod. I’ve not yet left Corregidor, but I’m already looking forward to the day I shall return.

John D. Lukacs, author of Escape From Davao: The Forgotten Story of the Most Daring Prison Break of the Pacific War, is a writer and historian whose work has appeared in USA Today and the New York Times. He visited Corregidor during a research trip to the Philippines for his upcoming book on the Battle of Manila, to be published by NAL Caliber in 2013. His website is johndlukacs.com.

When You Go

From Manila, Sun Cruises offers ferry transportation and day tours that include a buffet lunch, as well as overnight packages. Banca (native boat) operators provide service from Bataan and Cavite. Those interested in touring with the Kwiecinskis can learn more at their regularly-updated blog or contact them for reservations (steveontherock@gmail.com).

Where to Stay and Eat

You are a captive audience on Corregidor: there’s only one hotel, the Corregidor Inn, which has spartan but clean accommodations, dining, a pool, and a small gift shop. The peculiarly-spelled McArthur’s Café on Bottomside, not far from Lorcha Dock, serves Filipino delicacies including a delicious whole fried chicken dinner, and has the cheapest, coldest bottles of San Miguel beer on the island. Locals unwind at The Kiosk, located behind the Corregidor Inn.

What Else to See

Birds. Lots of birds. Birds—including Eurasian tree sparrows, emerald and zebra doves, and kingfishers—and bird watchers alike have been flocking to Corregidor in increasing numbers in recent years. The Rock is also an eco-tourism destination for hiking, mountain biking, kayaking and sailing, plus other environmentally friendly recreational pursuits. Philippine sunsets are among the most beautiful on Earth, and the best place to enjoy one is at Battery Grubbs on Topside, in the west central part of the island.