California’s Empire Mine yielded some $120 million in gold over its 106 years of operation. The owner built himself a dream house that is now a museum.

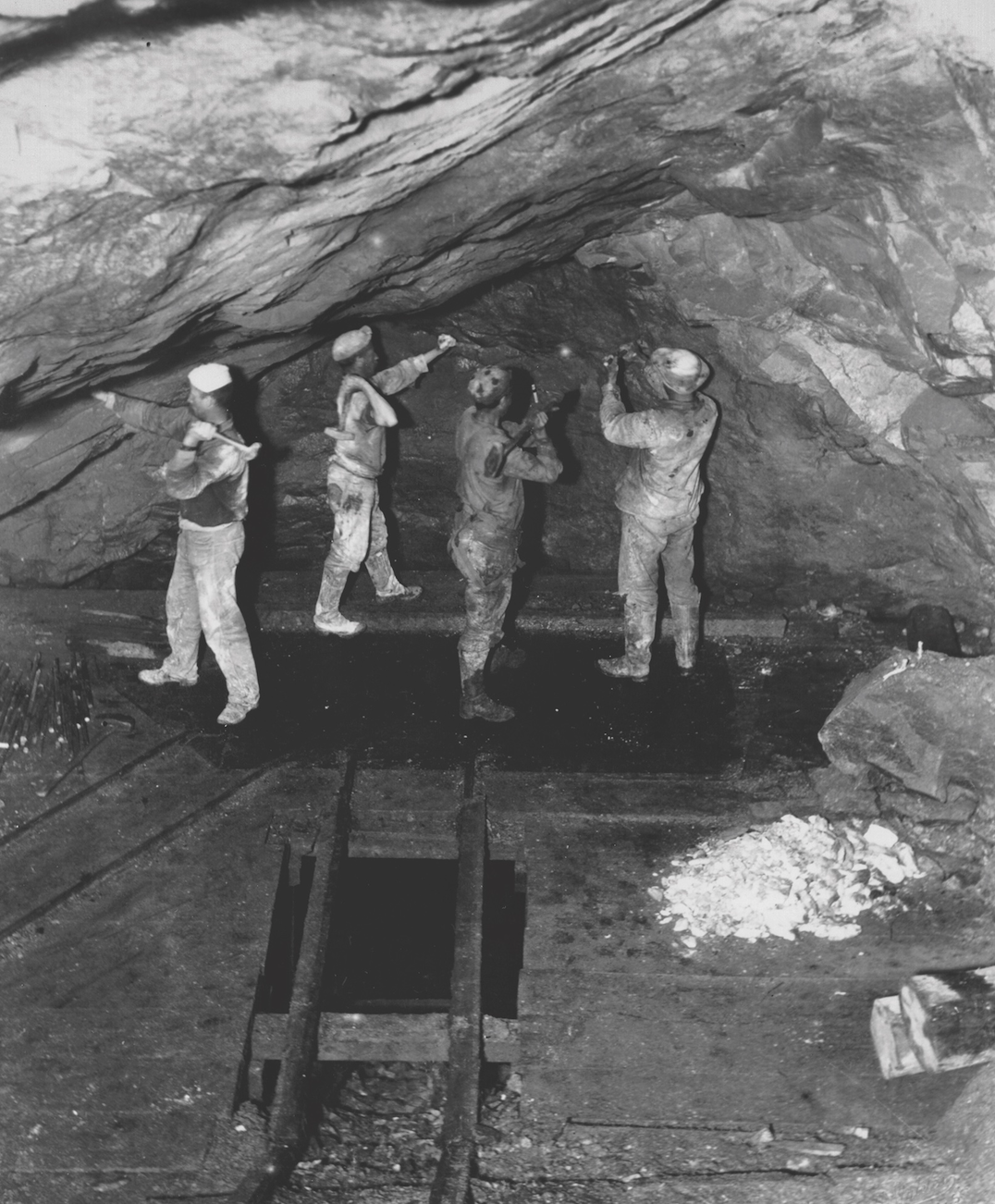

But the Cornish miners who brought their state-of-the-art drainage techniques from southwest Britain to the American West in the latter half of the 19th century were to thank for keeping the mine from going under, literally and figuratively.

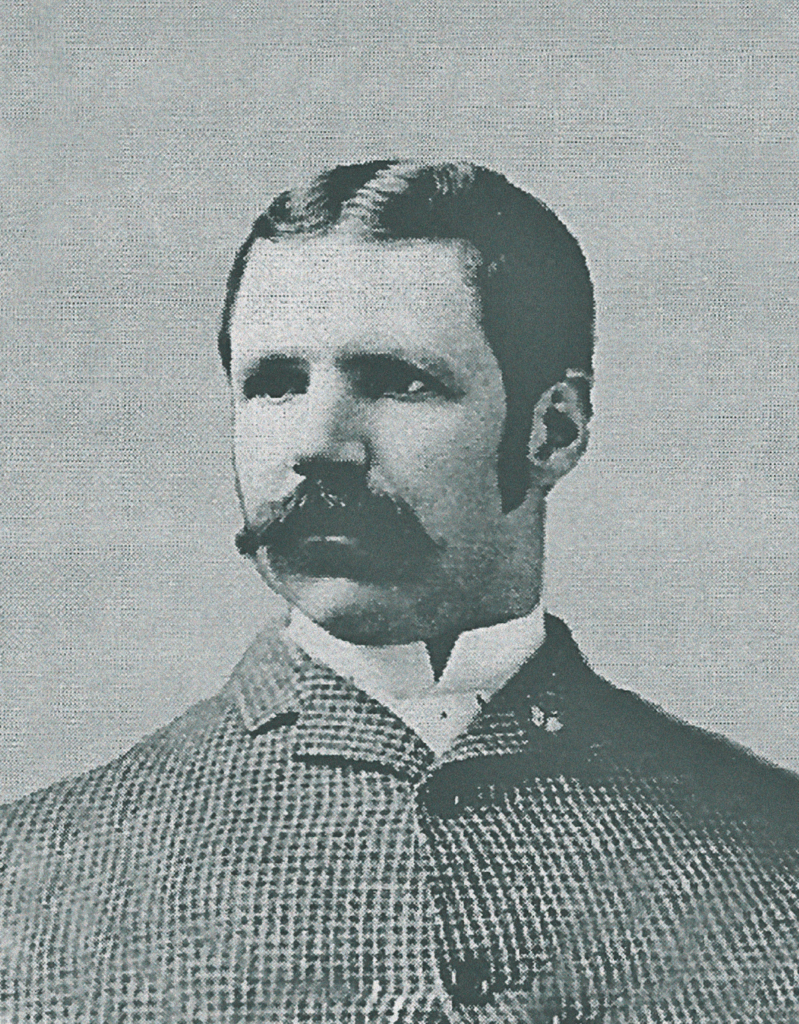

William Bowers Bourn joined the California Gold Rush in 1850. Originally from Massachusetts, Bourn had formed a mining partnership with father-in-law George Chase, a sea captain who had shipped freight—and Bourn himself—from New York to California.

While Chase and Bourn were better entrepreneurs than mining engineers, they knew a good thing when they saw it and invested in the Empire, a hard-rock gold mine in Grass Valley, in what would soon be San Mateo County.

Telltale Vein of Quartz

The mine dated from October 1850, when George McKnight spotted a telltale vein (dubbed the Ophir) of quartz suggestive of rich ore content. He sold the claim to Woodbury, Park & Co., and the mine passed through a succession of owners before William Bowers Bourn acquired it in 1869.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The Empire became the main source of the family’s very considerable income through the early 1870s. Bourn also headed the Fireman’s Fund Insurance Co., starting in 1866, and owned bank shares and a store in San Francisco.

Envious entrepreneurs credited the industrious newcomer with “Bourn luck.” But Bourn’s luck ran out. In 1872 his youngest son, Frank, died after falling from a garden wall at home. He was 10. Soon thereafter production at the mine started to drop.

In 1874 Bourn’s eldest son and namesake, William Bowers Bourn II, was learning the business alongside his father and about to embark for England to study the classics at Cambridge University, when more tragedy befell the family—that July 24 his father shot and killed himself at their Nob Hill home in San Francisco. A coroner’s inquest determined that while cleaning a revolver, the senior Bourn had dropped it on the floor, discharging it into his abdomen.

Saving the Family Fortune

When young William left for England, the estate assumed operations at the Empire. But by 1878 the mine was in deep trouble. The ore seemed to be playing out, and water seepage into the shafts had rendered the mine inoperable. Widow Sarah Bourn appealed to her surviving son to return to California and try to save the wellspring of the family fortune.

Drawn by the Gold Rush, miners from Cornwall, England, had long been famous for getting the most out of troubled mines. On arriving home, Bourn hired a number of them to introduce their hands-on skills and innovative technology.

Empire management had abandoned the Ophir vein when it bottomed out at 1,200 feet, and water had come in faster than they could pump it out. But Bourn’s Cornishmen knew of an engine that could pump 18,000 gallons of water a day, thus clearing the shaft and opening the door to further exploration.

Cornishmen’s Innovations

The Cornishmen also introduced Lester Allan Pelton’s newly invented water turbine to provide electric power. Given new life, the Empire was soon producing enough gold to set accounts right again.

Like his father, Bourn preferred wheeling and dealing to digging—selling shares when things looked up and buying them back when things looked bleak. When things looked rosy in 1888, Bourn sold his controlling interest in the Empire to James D. Hague and moved over into the wine industry, joining with E. Everett Wise and other investors to build Greystone Cellars in Napa Valley.

Bourn bought out Wise, only to reverse course and sell all his interest in Greystone in 1894 during the phylloxera scourge that blighted the grapes. Two years later he picked up where he left off, retaking control of the Empire during a relative downturn in gold production.

Branching out into public utilities, Bourn merged electricity and gas companies into what eventually became Pacific Gas & Electric and acquired a controlling interest in the Spring Valley Water Co. The resulting set of business circumstances painted him a populist villain at the time and in retrospect a champion of the environment.

Right to Profits

The San Francisco Chronicle pilloried him for his high water rates and charged that he opposed construction of the proposed O’Shaughnessy Dam and Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, within Yosemite National Park, out of greed. Conservationist John Muir (echoed by present-day ecologists) cited the forthcoming project as an environmental catastrophe that would obliterate a valley thriving with wildlife and natural beauty. For his part Bourn replied his business had a right to profits.

Siding with Muir, he long fought the project, albeit not in the spirit of environmental altruism.

The next technological innovation Bourn pioneered at the Empire was the use of waste rock as block stone and binder for cement, commissioning architect Willis Polk to test the concept in the construction of the Empire Cottage, with greenhouse, tennis courts and a reflecting pool, near the mine.

Bourn later sold the construction material commercially. In 1910 Bourn had a cyanide plant built on the premises, an improved process over chlorination to remove gold from the rock.

Wheelchair-bound after a 1922 stroke, Bourn finally sold out in 1929, heartbroken after daughter Maud died at her own estate in Ireland. The mine kept producing through 1956, ultimately yielding 5.8 million ounces of gold from 367 miles of underground passages.

A California Landmark

The California State Parks system now operates the aboveground site as the Empire Mine State Historic Park. A California Historical Landmark, the park is on the National Register of Historic Places.

A three-hour drive south of the Empire is Filoli, Bourn’s sprawling, art-filled mansion in San Mateo, designed by San Francisco architect Bruce Porter and set amid 16 acres of formal gardens. Completed in 1917, the 36,000-square-foot manor boasts 43 rooms, including a formal ballroom, nine family bedrooms, 17 bathrooms and 17 fireplaces.

For years the origin of its unusual name remained a topic of speculation. Bourn cleared up the mystery in the 1920s, explaining that it was an acronym for “Fight for a just cause; Love your fellow man; Live a good life.” The master of the manor died on July 5, 1936, and is buried atop a knoll overlooking Filoli.

The article was originally published in the February 2018 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.