Walt Ehlers will turn 91 this May, but his memories of landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day and fighting until V-E Day haven’t dimmed. Staff Sergeant Ehlers of the 1st Infantry Division killed dozens of Germans and was wounded three times. He earned three Purple Hearts, a Silver Star, and America’s highest tribute, the Medal of Honor—one of 464 bestowed during the war. Equally vivid are Ehlers’s memories of his older brother Roland. The Kansas-bred Ehlers boys enlisted together at Fort Riley in 1940 and fought in the same company in North Africa and Sicily, but Walt was transferred to another while training for D-Day. On the same June 6 morning that Walt got off Omaha Beach, Roland was killed there.

Walt Ehlers will turn 91 this May, but his memories of landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day and fighting until V-E Day haven’t dimmed. Staff Sergeant Ehlers of the 1st Infantry Division killed dozens of Germans and was wounded three times. He earned three Purple Hearts, a Silver Star, and America’s highest tribute, the Medal of Honor—one of 464 bestowed during the war. Equally vivid are Ehlers’s memories of his older brother Roland. The Kansas-bred Ehlers boys enlisted together at Fort Riley in 1940 and fought in the same company in North Africa and Sicily, but Walt was transferred to another while training for D-Day. On the same June 6 morning that Walt got off Omaha Beach, Roland was killed there.

The army separated you and Roland because of the five Sullivan brothers, who died together on the USS Juneau.

They didn’t separate us by much: Roland stayed in K Company, and I was transferred to L and got promoted to staff sergeant. My squad had a violinist, an accordion player, a guitarist, a singer, and a boxer. None of them had been in combat before. Because I had experience fighting the Germans, I always took the lead.

Describe your D-Day landing.

We were loaded on an LCI [landing craft, infantry] at Weymouth. We were supposed to be part of the second wave; the first wave went out on Higgins boats. When the first wave got pinned down on the beach, I heard one of the commanding officers say, “We’ve got orders to send more troops in immediately.” My squad and I went over the LCI’s side into a Higgins boat. We hit a sandbar 100 yards out. They let down the ramp and off we went. The water came up to my neck; it was over some people’s heads. For some reason there was no shelling or firing right at us.

How did you get off the beach?

The beachmaster said, “Just follow that path and go as far as you can; if you go to the right or left you’ll step on landmines.” We saw the dead and wounded alongside as we went. We got through two rows of wire that were blown, but there was a third row, which wasn’t. There were pillboxes to the right and left and two higher up in between. The two Bangalore torpedo men who’d blown the two rows of wire were pinned down by a sniper. I told them, “My squad and I will fire up on the German trench there if you guys get up and blow the wire for us.” One of them got shot, but the wire was breached. My men rushed the trenches connecting the German positions and ran the Germans out of them. Using the trench, we captured the top pillbox from behind.

How long did that fighting take?

Six hours. But all 12 of us got off Omaha Beach without a man wounded, which was a miracle. My squad was amazed. There were so many bodies everywhere. It was 60 times worse than Saving Private Ryan.

Then you led a reconnaissance patrol that found a German briefcase.

When they opened it up at HQ, they found maps of the Germans’ lines of defense for their retreat. So the next morning—June 9th—they sent us out on the attack near Goville. I didn’t know there were pillboxes there; I hadn’t seen the maps. But I was thinking, we’re out here in the middle of a field, all these hedgerows around us; doesn’t seem like a good idea. The platoon over to our left suddenly got fired on by a machine gun. We hadn’t been fired on yet. So I rushed the troops up to the hedgerow and went down along it toward the sound of the machine gun. I heard a rustle on the other side and saw four Germans with their guns pointed at us. So I shot all four of them through a small opening in the hedgerow. That made an impression on my squad. I was always the first one out, so the guys were willing to follow me.

What about the Germans still firing at you?

Two machine guns set up a crossfire to protect two 80mm mortars. I crawled along the hedgerow toward the first machine gun. I was exposed, but they didn’t see me, so I shot them. The second machine gun was across the field; they didn’t see me either, so I shot them. I had my squad fix their bayonets. When the Germans on the mortars heard me yell “halt,” they started running. Then my guys came up on the hill. We were shooting ’em in the back but had no choice, unless we wanted to fight ’em again. We shot ten of them. There was still one machine gun left. So I had the squad cover me while I worked my way to get almost on top of it, then I took them out.

That action and the next day’s earned you the Medal of Honor. What happened on June 10?

My squad was ordered to take the lead across a field. We were being fired on from three sides—the hedgerow going across in front of us, one to our left, another to our right. We were going up a hedgerow in the middle. Then the company commander told us to withdraw. I knew we were being surrounded. I also knew if we turned around, they’d shoot us all in the back. So I went up with a BAR [Browning automatic rifle] rifleman to where there was ensilage cover—cattle feed—and got on top of that to see over the hedgerows. I fired in a semicircle to the left as the BAR man fired to the right. When the squad got out through the hedgerows we turned to go back. I saw the Germans putting a machine gun about 100 yards away and was shooting at it and hitting them. Then I got hit in the back; it spun me around and knocked me down. When I got up I saw the BAR man was hit. I got him and carried him back, and went back and got the BAR.

How badly were you wounded?

How badly were you wounded?

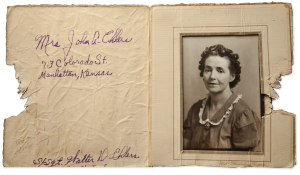

It went through a muscle and glanced off a rib, then went into my pack and hit a bar of soap and came through my mother’s picture and out the back of my pack. I was very lucky; it was very close to my spinal cord. I’m on dialysis because of the kidney condition it caused. I still have that picture of my mother, with that stern look on her face that says “how dare they!”

But you went back to the front ASAP.

Until we finally got our relief to get showers and new clothes for the first time since we landed. That’s when I found out my brother was dead: July 14th. I’ll never forget that date. Then we had to pack up and leave for the breakthrough at St.-Lô. We got bombed there one night and I got hit, a serious wound that went about nine inches into my left thigh, just missing my testicles. I went back to Cherbourg; I wasn’t going to be foolish this time.

Where did you rejoin your outfit?

At the Hürtgen Forest, where I got hit again—both shoulders and the right leg.

How did you learn that you received the Medal of Honor?

From a guy who was reading Stars and Stripes on the train bringing me back to the hospital. I got promoted to Second Lieutenant in Paris. They sent me home on 30 day leave—not because of the medal but because I had more points than anyone in the division. I was heartsick at home, because the Battle of the Bulge was going on. I got back in January and took over a platoon. We had a lot of combat. I got wounded in April 1945, in the right leg. I’ve still got the bullet in there. The Germans didn’t leave much of me untouched.

When did you come home?

I got discharged October 1945. It wasn’t easy. I had to explain to some people why I didn’t go back and look for my brother. They didn’t know what that shore looked like. Man, you never saw such devastation. They were still shelling the beach. I saw the second wave come in but didn’t know my brother had been hit. A couple days later some guys from his outfit said he was missing in action. I knew he must’ve been killed or wounded. I had to believe he was still alive up to the time I was notified by the company commander that he’d been killed. He said it was a mortar, but a platoon sergeant who witnessed it said it was an 88 [artillery gun], which hit the squad coming down the LCI ramp. I’ve had dreams about him coming back for more than 50 years.