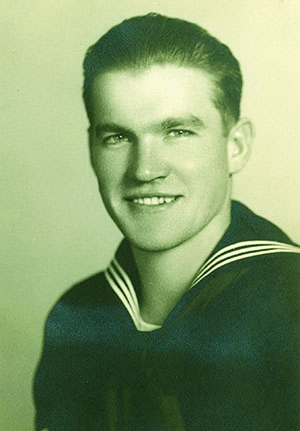

Jim Downing, 103, was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and joined the U.S. Navy in 1932, hoping to see the world outside his hometown. After six months at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center, he went aboard USS West Virginia in California. As a gunner’s mate, he manned one of the battleship’s four 16-inch gun turrets, which fired 2,000-pound shells as far as 21 miles.

The U.S. Pacific Fleet moved from the California coast to Hawaii in 1940. How did you feel about the move?

None of us felt very good. Pearl Harbor wasn’t equipped to handle that many ships—no logistics. It felt like a sudden decision; we were there on routine maneuvers and then the word came from Washington to stay. We had to move all of our supply ships out there, too. And Honolulu was so crowded—there were about 86,000 military personnel from the navy, army, and Marines. We weren’t very happy about that.

How did you feel about being aboard a battleship? What was that like in those days?

The first thing you had to get used to was constantly rubbing elbows with someone. Although a battleship is 624 feet—two football fields long—it has a crew of about 1,500 men. That’s quite a crowd for a small ship, so there’s only about six square feet per person.

Where were you living on December 7?

I lived just barely out of the city, away from the navy yard. We had a crummy apartment for which we paid $32.50 a month.

What was your first inkling that something was wrong?

I heard the explosions. We heard rumors that British cruisers were chasing a German surface raider in the Pacific. So I thought they had forced the German ship to come to the harbor. Under international law, a belligerent ship could come into a neutral port and stay 24 hours. After that, they had the choice to either surrender or go out and fight.

Then we turned on the radio and heard a voice say, “We have been advised by army and navy intelligence that the island of Oahu is under enemy attack.” It was not unusual to see American aircraft flying around on Sunday mornings, and many Japanese planes were painted olive-green, like ours. The first Japanese bomber I saw was slowly flying low toward where I was standing. After it passed by, the machine gunner turned loose, firing bullets right over my head. That was the moment I realized the war was very personal.

How did you get to your ship?

Shore boats that went between Battleship Row and the navy yard were diverted to pick up sailors in the water, so we took a ferry to Ford Island. I went aboard the Tennessee, which was next to the West Virginia, swiveled a 5-inch gun to one side, and slid down the barrel onto my ship.

What was your first action?

Everything above the water line was on fire. The battleships had accumulated about 20 years’ worth of paint, and that made good fire material. The fire on the Arizona was so hot that oil burned on top of the water.

I could see flames working back from the bow on the West Virginia, and I was afraid the fire would light off our guns’ ammunition and cause secondary explosions. So I got a working firehose off the Tennessee and started dousing the ammunition to cool it off. But I saw several bodies lying around and thought, “their parents will never know what happened.” Every sailor wore a fireproof name tag on a lanyard, so I went around trying to memorize their names with the idea of writing to their parents. That’s what I did until the fires were all out. I wish I could remember how many names I collected. At least a half dozen.

By then, had the ship settled all the way to the water line?

Yes. Of the 40 torpedoes the Japanese dropped that morning, nine hit the West Virginia, tearing a 140-foot hole. We lost all electrical power and the ship started to list, but our damage-control people counter-flooded and got the ship level, after which it settled on the bottom.

How long were you aboard the West Virginia after the attack?

Before Captain Mervyn S. Bennion was killed, he had given word to abandon ship. But there were several of us that saw no reason to leave, so we stayed to put out the fires, which took about an hour and a half.

After we put out the flames, I went to the hospital to see one of my friends who had been burned. I saw all these men in suspension on cots—burned, blind, or with their hair burned off. I took a notebook and told them if they could give me their parents’ address and dictate a short paragraph, I would see to it that their parents got it. I spent the afternoon of December 7 going up and down that line, taking dictation for those guys.

What were your duties in the weeks after the attack?

As postmaster for 1,500 people—which is a small town—I had a full-time job on my hands. Christmas mail had begun to roll in. I had to forward mail to crew who were transferred to other ships and return mail addressed to sailors that had been killed.

It took a year and a half to raise the West Virginia and get it going again. After a few months, we started building up a new crew to take the battleship back to the States. In May 1943, the West Virginia sailed to Bremerton, Washington, and was rebuilt at Puget Sound Navy Yard.

Have you come back to Pearl Harbor since the war?

My ship was located there and I lived there from 1952 to 1955. I’ve attended four annual reunions, including the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, and I’ve been coming periodically ever since. Now we’re up to the 75th!

How did returning affect you?

The picture of Pearl Harbor I had when I left was of awful destruction: the Utah sunk, the Arizona on the bottom, flames and smoke everywhere. I had a hard time getting used to returning, mainly because people living there at that time didn’t know anything about the war. And it’s hard to find reminders of the war at Pearl Harbor today. There’s a few bullet holes in buildings at Hickam Field and the Arizona Memorial, but that’s about the only remaining evidence of the war. Life moves on.

After going through such an experience, how often do you think about what happened to you and your friends that day?

Somehow, I don’t think about yesterday and I don’t think about tomorrow. Today is so much fun! Why worry about all that? So, I try to be realistic. It happened, it’s history. None of it can be reversed. Why mourn over all that? Instead, just look forward. ✯