During the Cold War years, Convair’s delta-wing F-106A was the fastest and most lethal all-weather interceptor in the U.S. Air Force inventory. The F-106A, when lightly loaded, approached the magic 1-to-1 thrust-to-weight ratio—a characteristic coveted by fighter pilots everywhere. With a 24,500-pound-thrust afterburning Pratt & Whitney J75-P-17 engine pushing an airframe only slightly heavier than the engine thrust output, this 1950s-era airplane had an impressive initial climb rate of 30,000 feet per minute and a zoom-climb altitude above 70,000 feet. As a result of the “thermal barrier” created by friction heat on the ship’s skin and Plexiglas canopy, its airspeed was limited to Mach 2.31 (1,525 mph).

The genesis of the fighter that ultimately became the F-106A, and later the F-106B trainer, began in 1949 as Project WS-201A. The concept called for a supersonic fighter-interceptor carrying air-to-air guided missiles, with an all-weather search and fire-control radar.

The Hughes Aircraft Company was awarded the armament and electronics contract in October 1950. Hughes developed the MA-1 fire-control system, designed to fire a nuclear-tipped Genie rocket and/or four Super Falcon radar-homing, infrared heat-seeking missiles. (In 1972 an internal Vulcan 20mm cannon package would replace the Genie on some F-106As.)

The airframe development contract was originally presented to Convair, Lockheed and Republic. Convair’s proposal ultimately won the day, since it was closely related to the company’s earlier efforts on the delta-wing XF-92A. The delta-wing design had evolved from the work of Alexander Lippisch, who pioneered the concept in Germany during World War II. Based on the XF-92A experience, Convair’s management remained convinced that the delta-wing configuration was the best answer to problems encountered with supersonic flight.

The Air Force wanted the interceptor to be operational in 1954, but by December 1951 it became apparent that neither the engine nor the MA-1 fire-control system would be ready by then. Meanwhile, Convair proceeded with development of an interim version designated the F-102A Delta Dagger. It fell short of the Air Force’s required performance, however, so Convair made several changes to the airframe and engine. The new J75 turbojet replaced the original Pratt & Whitney J57. While the delta wing remained essentially unchanged on the first few test aircraft, the F-102A’s fixed leading edge and wing fence were subsequently replaced with leading-edge wing slots. The fuselage was stretched and streamlined using NASA’s “Coke bottle” area-rule design, with the air intakes moved closer to the engine and well aft of the nose. For flights at very high Mach numbers, automatic variable inlet ramps moved fore and aft as airspeed changed to keep the inlet air flowing into the J75’s compressor subsonic.

The resulting airplane, initially designated the F-102B, had been altered to such a degree that in 1956 it was redesignated as a new type, the F-106A Delta Dart. By August 1958, four years later than originally planned, the “ultimate interceptor” was complete, entering service in May 1959. Its combat radius with internal fuel was 575 miles, and its range could be extended to 2,700 miles with external tanks. The airplane’s service ceiling was 57,000 feet. At 35,000 feet, the Delta Dart was capable of interceptions at speeds up to Mach 2. On December 15, 1959, Major Joseph W. Rogers flew a stock F-106A to set the world’s absolute speed record for single-engine aircraft of 1,525.695 mph.

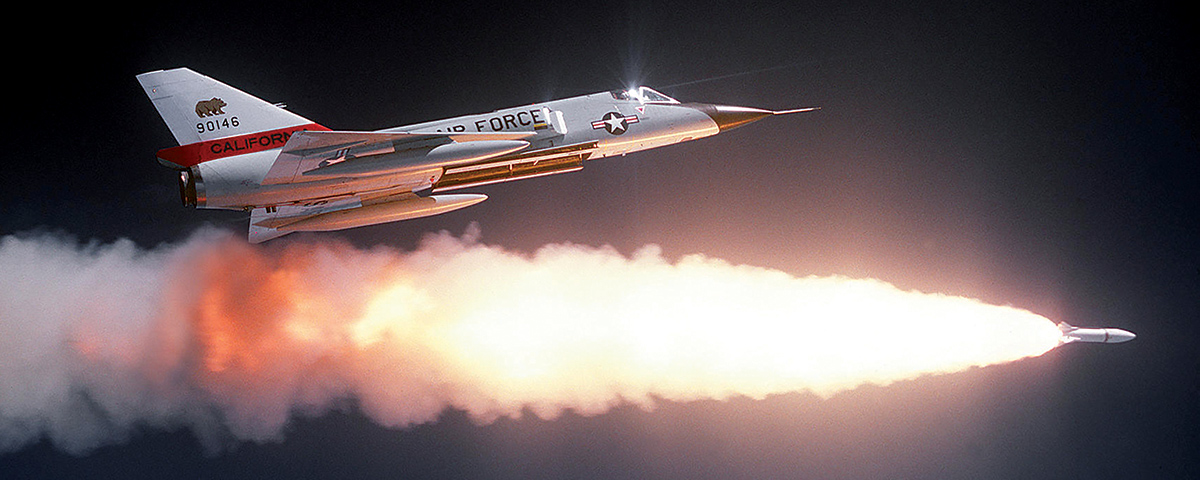

Armament, housed in a ventral weapons bay, consisted of four Hughes AIM-4 Super Falcon air-to-air missiles, along with a single Douglas AIR-2A Genie air-to-air rocket with a 1.5-kiloton warhead. These were intended to be fired at enemy bomber formations.

The MA-1 fire-control system was designed to work in conjunction with the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) continental air defense network. After takeoff, the MA-1 system took control of the airplane (though the pilot provided throttle inputs) and a SAGE ground controller guided the F-106 to the intercept, whereupon the pilot would lock on the intruder and fire his weapons. The SAGE controller then returned the Delta Dart to the vicinity of the air base, where the pilot again took control and landed.

Ultimately, the initial F-106A order was reduced from 1,000 aircraft to 277, plus 63 two-seat, dual-control F-106Bs, outfitting 14 squadrons and a training unit. The reduced order reflected the evolving Soviet threat, which had shifted from an emphasis on bombers to ballistic missiles. The last F-106A was delivered on July 30, 1961.

In late 1961, the Air Force conducted Project High Speed, pitting the F-106A against the U.S. Navy’s McDonnell F-4 Phantom II. While the F-106A bested the F-4 in visual dogfighting, the Phantom’s APQ-72 radar proved more reliable, with longer detection and lock-on ranges. That December the USAF announced that Tactical Air Command would acquire the F-4, with the F-106A remaining in Air Defense Command’s inventory.

In 1965 the Weber Aircraft Corporation was tasked with designing a “zero-zero” ejection seat to replace the F-106’s unpopular and complicated conventional ejection seat. Weber delivered the first new seat in just 45 days, and it proved highly effective. Ejection with the Weber seat was a one-step procedure: The pilot simply raised the armrests, which jettisoned the canopy and ignited the first stage of the two-stage rocket catapult. The booster rocket started the seat up the rails and then the second stage provided upward and forward thrust so that both seat and pilot cleared the ship’s tail. The new seat was subsequently retrofitted on the entire F-106 fleet.

During its long service life, the F-106A had the distinction of recording the lowest single-engine aircraft accident record in USAF history. The Air Force began replacing its Delta Darts with McDonnell F-15s in 1981, keeping many in service as QF-106 target drones. The last F-106A was retired from the 119th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, New Jersey Air National Guard, in August 1988. Yet even today the Delta Dart could hold its own in the fighter training and combat arena, and Major Rogers’ speed record for a single-engine jet still stands. That’s quite an accomplishment for an airplane that first flew more than 60 years ago.