On March 4, 1861, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives convened as the 37th Congress the day Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as president. In his inaugural address, Lincoln took a conciliatory stance and promised not to interfere with slavery in states where it existed, but the antislavery congressional Republicans who became known as Radicals insisted that the power to shape the course of the war resided in the legislative branch, not the White House. In Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought the Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, and Remade America, historian Fergus M. Bordewich explores how the 37th and 38th Congresses pushed the president to fight the Confederacy aggressively, emancipate the four million African Americans in bondage and protect their civil rights, and enact legislation that made the federal government stronger.

By Fergus M Bordewich

Alfred A Knopf, 2020, $30

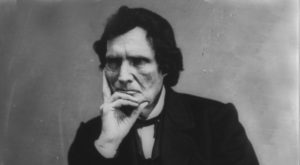

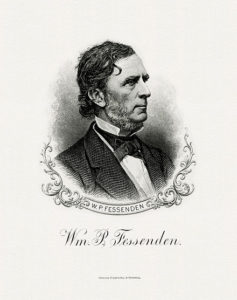

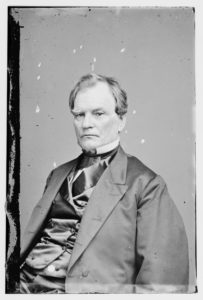

You identify four legislators who were central characters during the Civil War. Who were they? Two were leading Radicals, Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Ben Wade of Ohio. Both were consistent advocates for an aggressive war policy and forceful action to liberate the South’s slaves. Another, Senator William P. Fessenden of Maine, a conservative by nature, only belatedly and cautiously aligned himself with the Radicals; as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, he was a pivotal figure in raising money to carry on the war. The fourth, Ohio Representative Clement L. Vallandigham, a staunch Copperhead, was a northern Democrat with southern sympathies and the leading advocate for a negotiated peace.

What were the main challenges facing Congress in 1861? The challenges that Congress faced were existential: How could the North be mobilized for a war it never expected to fight? How could the war be paid for? Could the Constitution survive the suspension of fundamental civil rights in the name of national security? Should the war be fought with respect for the sanctity of Southern property—including slaves—or with a ruthlessness that would bring the seceded states to their knees? Suspicion of central government, distrust of a strong executive, and traditions of states’ rights—in the North as well as the South—threatened to undermine the country’s war-making ability, while deep-seated racism threatened to infect every war policy that touched on the future of black Americans.

What were the main achievements of the special session of the 37th Congress that met July 4, 1861-Aug. 7, 1861, and what was the backdrop for their actions? In effect, the special session made the war a reality. Passage of the Confiscation Act facilitated the liberation of enslaved people as “contraband of war,” and began the march toward general emancipation. The biggest war loan in American history to that date was approved, and the first income tax was enacted. Money was appropriated to pay the troops, buy arms and ordnance, construct fortifications and develop armored ships. The size of the Navy was dramatically increased. The president was given the authority to mobilize state militias for the war’s duration. Federal employees, for the first time, were required to swear a binding oath of allegiance. The Philadelphia Daily News proclaimed, “This extra session has been, in many respects, the most remarkable of any held since the adoption of the Federal Constitution.”

Congress supported unilateral actions taken by President Lincoln in the opening weeks of the war, except for his decision to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Can you explain the significance of habeas corpus and how the president’s decision affected the war effort? Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus was an emergency response to acts of sabotage and subversion by southern sympathizers in Maryland. Suspension enabled the military to arrest and hold civilians as suspected saboteurs without due process. Democrats and some Republicans protested at this perceived assault on civil liberties, but if Lincoln had not acted Washington and its small military garrison would have been cut off from reinforcements from the North. It took many months for Republicans to rally behind Lincoln on the issue of suspension, and many did so with lingering moral qualms.

Congress, with Republican majorities in both houses, was ahead of the president on emancipation. What actions did legislators in the 37th Congress take that pushed Lincoln toward freeing slaves? In passing the Confiscation Act, Congress invented a strategy for giving runaway slaves safety within Union lines, in defiance of the Fugitive Slave Law. In 1862, Congress voted to free all remaining slaves in the nation’s capital, while powerful Radicals such as Thaddeus Stevens urged Lincoln to adopt general emancipation as a war measure. This the president finally committed to a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 and formalized the proclamation on January 1, 1863. Although it applied only to areas under federal control, the proclamation made clear federal determination to destroy slavery everywhere. As early as 1862, Radicals in Congress also began pressing for the recruitment of former slaves and free African Americans as soldiers, which became official policy in 1863.

One of the most controversial moves of the 37th Congress was formation of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Why was the committee so significant to military policy and public opinion? The Joint Committee was the driving engine of congressional war policy, prodding and pressuring Lincoln to take more aggressive military action and to act more decisively against slavery. The committee interviewed hundreds of serving army officers about their strategy, tactics, and management, and publicly challenged those, such as Maj. Gen. George McClellan, who it considered insufficiently committed to a hard-war policy. The committee also vigorously investigated war profiteering, the treatment of federal prisoners in the Confederacy, and the horrific massacre of black federal troops at Fort Pillow, in 1864. The committee was criticized both during the war and afterward as an example of unjustifiable civilian interference in war-making. Its defenders replied that through the committee Congress was in fact carrying out its constitutionally mandated duty of oversight. Had the committee been less forcefully led—it was chaired by the Radical Sen. Ben Wade of Ohio—McClellan and cautious generals of his type would likely have remained in command far longer and pressure to the recruitment of black troops would have been far weaker.

Congress enacted innovative legislation that continues to affect the country in the 21st century. Can you talk about those bills? The Civil War era was one of the most dynamic periods of legislative activism in American history. Congress made the Union victory possible by raising the astronomical sums necessary to keep the war effort afloat by enacting the innovative sale of war bonds and the country’s first income tax. It also reinvented the nation’s financial system, in part through the issuing of the first national currency, and passed far-reaching legislation that was long blocked by prewar southern intransigence: in particular, western homesteading, the Transcontinental Railroad, and the establishment of land-grant colleges. By its determined support for emancipation, Congress also initiated the racial revolution that would overthrow the South’s cotton economy and eventually make citizens of nearly 4 million former slaves.

One of the most difficult and controversial issues that Congress debated was what to do with people perceived to be traitors because they supported the Confederacy. Talk about how Congress dealt with Copperheads. Copperhead agitation against the war ranged from argument on the floor of Congress, to polemics in the press, to organized subversion. A few Copperheads were summarily expelled from Congress, and the movement’s most prominent leader, Rep. Clement L. Vallandigham, was arrested and deported to the Confederacy. (He later returned to participate in the 1864 Democratic convention.) Beginning in 1861, after bitter debate, Congress sustained the suspension of habeas corpus, first in Maryland and parts of the Northeast and eventually across the country, enabling military authorities to crack down on extreme Copperhead activity. Enforcement varied widely and was sometimes capricious. Hundreds were arrested and jailed, and several newspapers suspended, though usually for only brief periods, prompting widespread uneasiness about the curtailment of civil liberties.

Another act that caused public unrest was the Enrollment Act of 1863. What happened as a result of this new law? The Enrollment Act enabled the War Department to draft men between 20 and 45 by lottery. It was the first conscription act in American history and a radical departure from the tradition of depending on volunteers to fill the army’s depleted ranks. In some areas, most notably those with large Copperhead populations, the public reaction against was intense, most violently in New York City, where hundreds were killed during days of rioting in July 1863. The Enrollment Act also established a system of provost marshals charged with arresting deserters, punishing “treasonable practices,” and seizing traitors and enemy spies. It further provided steep penalties for anyone who concealed a deserter, resisted the draft, or counseled anyone to do so. In some localities in the Midwest, the act led to rioting and bloodshed, including attacks on recruiting officers and draft offices, and the murder of 38 provost marshals by the end of the war.

Clement Vallandigham is seen most often as a reprehensible proponent of slavery and a traitor. You have a more nuanced view. Vallandigham, who represented Dayton, Ohio and became the most outspoken leader of the Copperheads in Congress, was an unapologetic racist and white supremacist who vigorously opposed the Union war effort in the most scathing terms. But he was a complex figure. He opposed capital punishment, advocated for the immigrant working class, and protested the brutal treatment of seamen on American ships. He tirelessly attacked racial “amalgamation” and “negro equality,” and charged that emancipation would cause millions of blacks to move north to steal white men’s jobs. At the same time, he defended traditional civil liberties against the actions of federal provost marshals and repressive measures such as the closure of Copperhead newspapers and the jailing of antiwar men for exercising the right of free speech. Had he espoused more enlightened policies on race and the Union, he might well be celebrated as one of America’s great wartime dissenters.

An abbreviated version of this interview appeared in the May 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.