The Civil War spawned a heroic myth that masked the true story

David W. Blight, a professor of American history at Yale University, is a former president of the Society of American Historians. He has written numerous books and essays, including

Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Simon & Schuster will publish his latest book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, in September.

More than 700 Confederate monuments exist in 31 states around the country. How did the losing side get so many? White southerners and Confederates had to be incorporated back into the Union. Ex-Confederates, especially toward the end of Reconstruction and during its long aftermath, were left to develop their own culture of defeat and their own rituals of memorialization. The white South was allowed to control and define race relations within those states. The memorial landscape came to represent, subtly and directly, the apartheid-style system that persisted from around 1900 until the civil rights movement. Race trumped reunion.

Did the South win the peace by romanticizing the Confederacy? There is a great deal of truth in this idea. As the Lost Cause tradition evolved, the old South—slavery, the very idea of race relations, and even the story of the emancipation of four million slaves in war—morphed into sentimentality about loyal slaves, kind and noble masters, and an agrarian civilization destroyed by the “Yankee Leviathan.” By the 1890s, the most popular writer in America was Thomas Nelson Page of Virginia. New York publishers and hundreds of thousands of Northern readers enjoyed In Ole Virginia, Page’s collection of stories about idyllic plantations and heroic Confederate soldiers aided by faithful, loving black retainers.

What was the “Lost Cause”? The idea of the “Lost Cause” started at Appomattox. General Robert E. Lee told his starving troops they had only been beaten by “superior numbers and resources.” The concept took hold among Confederate officers who wrote the Southern Historical Society Papers. Published for more than a decade, these documents chronicled a fight for home, for sovereignty, for honor and valor, and not, the authors claimed, for slavery. And there was the “Lee Cult,” promoted, in literary terms and later in other cultural forms, by Lee’s former officers. They portrayed Lee as the ultimate Christian soldier who fought to preserve his home state, not slavery. This was false. Lee fought for the Confederacy, and knew the Confederacy existed to preserve slavery—there is no question about that.

Did women play a role? Absolutely. Southern white women, especially daughters of Confederate veterans, became the driving force behind commemoration. The United Daughters of the

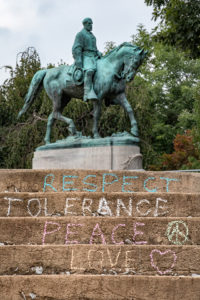

Messages drawn in chalk on the steps leading to Charlottesville, Va., statue of Robert E. Lee, a day before the Unite the Right Rally, August 11, 2017 .

Confederacy, with branches all over the country, forged a Lost Cause ideology that not only sustained the idea of Southern men’s heroism but a racial ideology that served the Jim Crow system. By the 1890s, with women in the lead, joined by the United Confederate Veterans, the Lost Cause had coalesced into a series of beliefs and ideas about victory—over Reconstruction. The Lost Cause became a celebration of defeating Reconstruction and racial equality.

Many Confederate monuments date to two periods—the late 1800s through the 1920s and the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s. Are they political gestures? There is a political component to the building of any monument. By the early 1900s, the power structure of the South, and to an extent the larger nation, took its lifeblood from the ideology of white supremacy. Even common soldier monuments, with their generic figure leaning on his musket, were symbols of a South that needed to remember its sacrifices and to demonstrate its newfound social and political control over its racial system.

How should we deal with what you call “memory stones”? A community or institution contemplating removal, alteration, or relocation of monuments should create a body that includes a historian or two to research the monument’s origins and meaning. Don’t avoid the political circumstances. Let many voices be heard. Second, approach this process with historical and moral humility. One person’s hated statue might be sacred to another. None of us are pure in our motives. Have the courage to know that change does and must occur—to institutions, to ideas and norms, to memorialization, to our understandings of history itself. You can’t “change history,” but we are all responsible for telling the world how we will interpret history in the public square. Before acting, learn more history. Don’t fear historical expertise or worry about aesthetics or trauma, about the notion of the sacred. We need to think not only with our identities but with informed minds.

Some say Confederate monuments represent “heritage, not hate.” History and memory are not the same thing. History is based on reasoned research. Memory is born of groups and forged in myriad ways; passed down generation to generation, it tends to be more emotional and sacred. “Heritage” can make us want to own a past, a story, a place against all other possible narratives or interpretations. A person using a symbol in public or in official ways must understand how the public views their actions. There is always going to be more memory than there is history, but those of us who are devoted to the craft of history have a deep responsibility to push back against memory even as we genuinely respect its power.