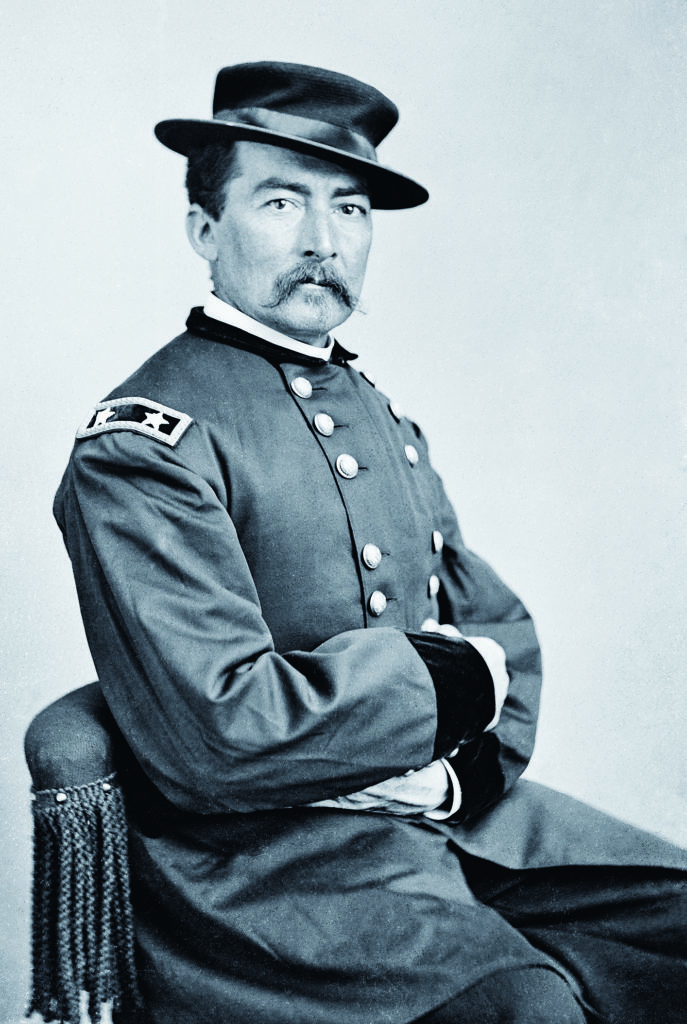

As the Union siege of Petersburg, Va., dragged on through the summer and fall of 1864, Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early led his Army of the Valley on a daring raid from the Shenandoah Valley that reached the gates of Washington, D.C., July 11-12. Turned back finally at Fort Stevens, Early retraced his route back through the Valley, pursued by Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s powerful Army of the Shenandoah. On September 19, Sheridan caught and routed Early at Winchester, Va., his 40,000-man force dwarfing Early’s Confederates by a 4-to-1 margin. The Third—and final—Battle of Winchester left the bloody battlefield strewn with more than 5,000 Union casualties and more than 3,600 Confederate dead and wounded. The dead, of course, were beyond succor; but the wounded of both sides desperately needed physical and spiritual help.

The Rev. James Sheeran, a Catholic priest serving as a Confederate Army chaplain, learned that many of the wounded left behind were from his unit—Brig. Gen. Zebulon York’s Louisiana Brigade in Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon’s Division of Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge’s Corps. Aware that no priests were present in Winchester at the time, Sheeran determined to journey through enemy lines to care for the injured and administer the sacraments to the dying. Sheeran secured a safe conduct pass from Union 6th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright. On the way to Winchester, the priest encountered Sheridan and his staff; in his diary, he writes that Sheridan’s adjutant affirmed his pass as legitimate.

Upon arriving in Winchester on September 26, Sheeran encountered a fellow Catholic priest, the Rev. James Bixio of Staunton, Va., whom he had met that summer. The clandestinely pro-Confederate Bixio had recently finagled an appointment from Sheridan as a Union Army chaplain. That appointment had given Bixio an opportunity to expand his smuggling activities supporting the Confederacy, and he asked Sheeran not to reveal his secret. Unfortunately for Sheeran, when Sheridan later became aware of Bixio’s nefarious endeavors, the general concluded that the Confederate chaplain, like Bixio, was also involved in anti-Union activities.

Sheeran faithfully kept a diary of his Confederate Army service, now published in its entirety by the Catholic University of America and edited by Patrick J. Hayes. The following entries, beginning with Sheeran’s thoughts on a late-October visit to Winchester by Sheridan, are from that diary.

Saturday, October 29

Gen. Sheridan is in town and visits all the hospitals. As most of our [Confederate] men were now sent off and few…needed my services, I resolved to see Gen. Sheridan, in order to know by what route he wished me to return home. I called at the Hdqrs. of Brig. Gen. Oliver Edwards, where the Gen. was staying, and knocking on the door, an officer whom I afterwards recognized to be [Edwards] himself asked me what I wanted….I told him my name and expressed a wish to see [Sheridan]. He answered me very roughly; told me to see his Adj., at the same time closing the door in my face. Anticipating some rough treatment, I thought it best to defer my visit to Monday and then bring a witness with me, so I took my departure.

Monday, October 31

This morning at 9½, accompanied by Capt. Fitzgerald, I repaired to the Hdqrs. of Gen. Sheridan. The Capt. introduced me to the Adj. Gen. of the Post….I then asked him if I could see Gen. Sheridan. He told me to take a seat and he would see. Capt. Fitz and I both took a seat and conversed…for some ten minutes, when the Adj. returned with an armed guard and told him to “take that man,” pointing to me, “to the Provost Marshal’s.” This I thought a singular proceeding, but, as I knew not what disposition they intended making of me, I was anxious to have Capt. Fitz accompany me, but this the Adj. would not permit and ordered the Capt. not to go with me for I was a d—-d old Catholic Priest.

I now found myself for the first time under a Yankee guard…[and in] the [Union] prison system.

Tuesday, November 1

Fearing lest he might possibly be ignorant of my arrest, I this day wrote to Gen. Sheridan a letter which I will hereafter insert and sent it by a Catholic officer who assured me that Gen. Sheridan received it…

[hr]

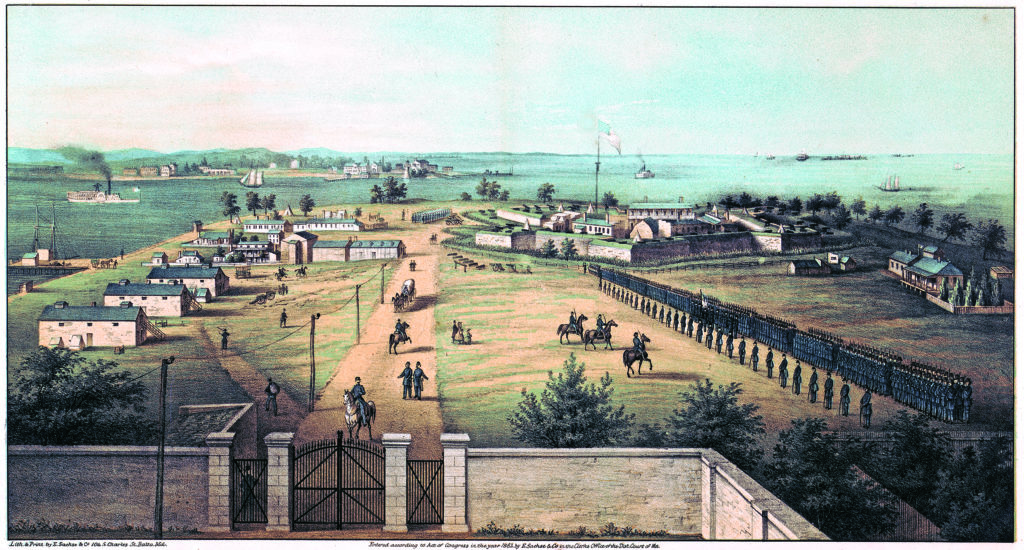

Sheeran was among a group of prisoners who left Winchester on November 4. Six days later, he was incarcerated in a stable adjacent to Fort McHenry in Baltimore. On November 12, he wrote James McMaster, editor of the New York Freeman’s Journal and Catholic Register. McMaster published Sheeran’s November 1 letter to Sheridan and a previously received letter from Sheeran, along with his scathing comments, under the provocative headline: “A Great and Cruel Wrong: Arrest and Imprisonment of a Confederate Catholic Chaplain.”

Outraged, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton squashed efforts to have Sheeran released. Sheeran, whose health was deteriorating, believed he’d die in prison unless he “dishonored” himself by pledging the required oath of allegiance to the United States. On December 4, Sheeran learned Sheridan had ordered him released if he signed a formal parole, which Sheeran did and then departed for Winchester. On December 30-31, Sheridan summoned the priest to his headquarters for an interview. Sheeran wrote about his confrontations with the general in his diary.

Friday, December 30

This forenoon Gen. Sheridan sends for me…. I now endeavored to brace up my nerves, for I was about to “beard the lion in his den.” In fact, I expected trouble with him, although I had a copy of his order for my release.

After some formalities I was introduced to a man, about five feet, six inches high [Sheridan was actually 5-5], with short legs and long arms, a low broad forehead and narrow face from about the nose down. His expression in my presence was that of a “hang man,” or perhaps a thief dog would better represent his looks, as I entered his room. In a dry and rather dogged manner, he invited me to sit down and then took a seat himself nearby….

Gen. Sheridan: “I understand you want a pass through my lines.” Yes, Gen., I wish to return home. “Well, you can’t pass through my lines.” Why so, Gen.? You ordered my release with permission to go home on condition I would give my parole to communicate no military information to the enemy. Now, Gen., I have given that parole and I demand that you comply with your part of the contract, for I consider it a contract which you, in honor and justice, are bound to fulfill. “I never intended that you should pass through my lines,” replied the Gen.

Well, Gen., I would like to know what you did mean….[Y]our words, although not very dignified, are very expressive and cannot be mistaken[:] “Release this man and let him go home, if he will give his parole.” Now, I would like to know how I am to go home, if I cannot pass your lines? Gen.: “I don’t want to argue the point, you will not go South.” There is no point to argue, Gen….If you meant what you said, you meant I should go home! But if you did not…the fault is not mine. I, however, shall hold you to the meaning of your words and shall go home.

“I never meant you should go home,” he again replied. I care not, Gen., for what you meant, you have made use of plain language and I will hold you responsible for what you have said. Now, Gen., I am determined to go home, cost what trouble it may….

The Gen., now beginning to droop his head and raise his temper, said in a flat, vulgar tone: “You shan’t go, now.” Well, Gen., I tell you candidly, if you give me any more trouble, I shall publish you again. “I don’t care if you do,” replied my friend in uniform. Then, sir, if you don’t care, I am sure I need not. I shall do it….

[hr]

Sheeran asked Sheridan to explain “what criminal or ungentlemanly act I have…committed since I came into your lines.”

He replied, “I don’t like the way you came into my lines.” That I cannot help, Gen., I came in, in an open, honorable manner and with a pass from Gen. Wright, which was verbally approved by your own Adjutant. “I asked my Adj.,” says Sheridan, “and he says he knew nothing about it.” Well, Gen., if he forgets it, I cannot help it. But I give you the word of a gentleman and a Catholic Priest that he did approve it….I told him very bluntly that as a gentleman I consider my word as good as his or his Adj., but in addition to this, I gave him the word of a Catholic Priest of good standing in the church and I thought he had no right to question it….[S]ir, why do you insinuate that I came into your lines in a dishonorable manner? Gen. Wright…treated me very kindly and gave me a pass. And now, Gen., in violation of this very pass, you have, without any charge or alleged crime, treated me in a manner unworthy of your profession as a Christian and a soldier…

[N]ow looking confused and angry, [Sheridan] says, “Father Bixio has acted in a manner unworthy of a Catholic Priest. He has deceived me and acted meanly.” I tell you, I am responsible for my own act[s], but not for those of any other man. Here he lets off another tirade against Father Bixio….I now, in a tone of indignation, remarked that I had long been in the Confederate army and had associated with its most distinguished Generals, but never was obliged to use any formality with them. Nor do I now feel obliged to use any with you; hence I tell you candidly, Sir, that it is neither just nor generous on your part to hold me responsible for the conduct of a man of whom I know nothing….He then somewhat coolly replied, “I know you are not responsible for his acts.” Well then, Gen., my question again recurs: What have I done to deserve the treatment I have received at your hands? He gives no answer.

[hr]

Sheeran then inquired, “[W]ill you be kind enough to let me know what course I am to pursue?” Sheridan answered that Sheeran could remain in Winchester or even return to Baltimore. “No, Gen.,” Sheeran countered, “that is not my home, I belong to the South and there I am bound to go.”

I always thought there was honor among the officers of your regular army. Now I ask you how would it look, in the eyes of all honorable men, were I to desert my command, as you suggest, by remaining within your lines? Such a dishonorable act, Gen., shall never stain my character. I prefer death even….

Here the magnanimous Sheridan holds his head a little lower, reflects for a few moments and replies: “I will think about it.” But, Gen., I would like you to decide upon it. It surely has been long enough under consideration. My means and health will not permit me to remain long here….My case requires medical treatment and I wish to repair to the Infirmary at Richmond for that purpose.

The fellow, now modifying his tone, said: “Why did you not make yourself known to me, when I came to Winchester?” I did, Gen. “Yes,” said he, “when you were in prison and could do no better.” I now, in some measure forgetting myself, or perhaps letting my temper get the upper hand, indignantly replied, Gen., you assert what is not true. I sought an interview with you twice before my imprisonment; and it was on the occasion of my second visit to your quarters that I was arrested….The so called brave but now cowardly Sheridan pulled in his horns and mildly said, “Well, I will give you a definite answer tomorrow.” So ended our first interview.

Saturday, December 31

[Sheridan] received me with a more agreeable tone of voice, but without daring to look at me in the face. Having invited me into his private room, we both took seats. After a moment’s pause and with his dogged and vulgar looking countenance cast toward the ground, he said, “I have a few questions to ask you….Do you know Father Bixio?” I know him, Gen., but have no particular acquaintance with him. “Does he stop at your house in Harrisonburg?” No, Gen., he does not; and that too, for one very good reason; I have no house there or any other place. “Did he not stop at your house, when our army was up there?” I have answered the question, Gen. I told you I have no house. “Did you see him in Harrisonburg before you came down to Winchester?” No, Gen., I have told you…that I met you and your army this side of Harrisonburg and Father Bixio, I understand, was in the rear of your army….”

“Well,” said he, “Father Bixio had treated me very badly. He engaged as a Chaplain in my army, obtained transportation, drew rations as such, he even obtained of my sutler in Harrisonburg a requisition for rations for the sick and wounded, alleging that he could distribute them to better advantage than the hospital nurses. Since then I have seen nothing of him, but have reason to believe he is corresponding with the enemy. Indeed I can look upon him in no other light than a deserter from my army.” He then gave a detailed history of Father Bixio’s “military career” up the Valley and in conclusion, appealed to me thus, “Now, Father, do you approve of his conduct?” No, Gen., I do assure you, I heartily condemn it. But, Gen., why do you implicate me in his actions? Had you taken the trouble to make yourself acquainted with my character, you would find that, if I have any particular fault, it is that I am too open and candid in my dealing with my fellow men. And I think, Gen., in our limited acquaintance, you must perceive that there is no double dealing about me. I may be sometimes imprudent; but I am honest and fearless, always doing what I conceive to be my duty, without respect to persons….As a Priest, I have never been under censure. As a Chaplain, I have always been at my post, discharging my duties fearlessly, and although not bound in justice, I have administered the sacraments to thousands of Federal soldiers on the bloody fields of Virginia, Md., and Pennsylvania and even at your hospitals. So I protest against being in any way identified with Father Bixio’s acts.

[hr]

Conceding he had been mistaken, Sheridan said Sheeran was free to go home as he pleased.

I was about to leave when the fellow, now rushing to be all kindness, told me not to be in a hurry….He then told me that he was a Catholic himself; that he was sorry to have any difficulty with a Catholic Priest, but that no person could blame him for taking care of his own affairs.

I would not blame you, Gen., said I, to use reasonable means of taking care of your own affairs. But you, or any other man, are not justified in condemning a person without a trial. Had you taken the trouble to investigate my case, you would have saved me a great deal of pain and yourself a great deal of censure.

This, then, was all the satisfaction the ignorant and evidently ill-bred creature made for the injury done me. Evidently the fellow was afraid of another tongue thrashing in the public papers; and hence his excuse in supposing me to be identified with Father Bixio was a fabrication made up since yesterday….

In parting with him I had to dirty my hand by shaking his, sustained as it is with blood, rapine and every species of injustice. The news soon spread…that Sheridan had to back down and let me go home, notwithstanding his strong declarations to the contrary…

[hr]

On January 3, 1865, with Sheridan’s pass in his pocket, Sheeran mounted his horse and headed for Richmond, arriving on the 10th. He checked into the infirmary the following day, where he remained until the city fell in April. Sheeran resumed his Redemptorist duties in Louisiana. After a few years, inexplicably, he requested to be released from his vows as a Redemptorist. It was granted, and he moved to Yankeedom, becoming pastor of the Church of the Assumption, Morristown, N.J., in October 1871. There he labored to heal the sectional wounds by espousing nationalism until his death April 3, 1881.

Adapted with permission of the Catholic University of America Press, publisher from The Civil War Diary of Rev. James Sheeran, C.Ss.R: Confederate Chaplain and Redemptorist, edited by Patrick J. Hayes.

_____

An Outrage on Religion

Extracts from James McMaster’s “A Great and Cruel Wrong: Arrest and Imprisonment of a Confederate Catholic Chaplain,” from the New York Freeman’s Journal and Catholic Register (November 19, 1864, pages 4-5).

The Rev. James Sheeran, of the Congregation of the Redemptorists, formerly a priest of St. Alphonsus Church in New Orleans, but since 1861 a Chaplain in the Confederate army, is now a prisoner in Fort McHenry….We have known Father Sheeran for many years. We knew him while he was a layman in Monroe, Michigan.

He is not only a devoted and excellent man, but one in the correctness of whose statements of fact, the utmost reliance can be placed….[W]e have been shocked and grieved at learning that Father Sheeran, notwithstanding his having a ‘pass’ from Gen. Wright, has been arrested, treated with gross indignity, thrown into a filthy guard room among Federal soldiers who were confined there for bad conduct and drunkenness; in this filthy prison, he was kept five days, obliged to listen to all the obscenity and blasphemy of the abandoned characters around him.

Nor has that been all….[H]e was thrust into a “Slave Pen” and kept there two days and nights, among the most degraded of soldiers there imprisoned for various crimes…

Now, till otherwise convinced, we must believe that there has…been a conspiracy against Father Sheeran; and that Gen. Sheridan is not acquainted with the facts. Gen.Sheridan has the reputation of an able and gallant soldier. He has, in some points, been paraded in a vulgar list of Federal Generals, discriminated very unwisely and improperly, “Catholic Generals.” Gen. Sheridan’s name and his native Perry County, Ohio, point him as a Catholic in religion and, almost certainly, as a student under the good Dominican Fathers. If he be an instructed Catholic, he knows well enough that no priest can absolve him till he makes reparation for the outrage he has committed on Father Sheeran. The devil would clap his hands and rejoice at any absolution given him without his entertaining the firm purpose of such reparation, to the best of his power.

For, even if, as we charitably suppose, Gen. Sheridan has been beguiled by some slippery member of his staff, now, so soon as he hears what has been done, he is bound to displace and to court-martial the aide that has deceived him.

The imprisonment of Father Sheeran is an outrage on the laws of war, for, as a noncombatant, as a minister of mercy, to all, he held Gen. Wright’s pass, which Gen. Sheridan’s chief of staff pronounced, “sufficient.” It was an outrage on religion….

The remnants of the [Union] Irish Brigade have reason to remember the little Irish Confederate priest, who lavished on them his spiritual and also his temporal aid, after Hooker’s battle of Chancellorsville. Father Sheeran, it was, that gave the last sacraments to the gallant Col. Mulligan. If Gen. Sheridan hopes, as no doubt he does, to die as chivalrously as Mulligan did, and as peacefully; let him hasten to make reparation to God and man for the outrage we have given thus publicity to, in order that it may be remedied.

This story appeared in the July 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.