Late in the war, General Josiah Gorgas advocated arming slaves to fight

Confederate armies never lost a battle because they lacked sufficient arms or ammunition. This achievement came despite formidable challenges and depended, to a significant extent, on the vision and efforts of Josiah Gorgas (1818-83). “In no branch of our service,” affirmed Jefferson Davis, “were our needs so great and our means to meet them relatively so small as in the matter of ordnance and ordnance stores.” The chief executive looked to Gorgas, “a man remarkable for his scientific attainment, for the highest administrative capacity and…zeal and fidelity to his trust,” to produce results “greatly disproportioned to the means at his command.”

The Pennsylvania-born Gorgas graduated sixth in the Class of 1841 at West Point, served as an ordnance officer during the war with Mexico, and married the daughter of a former governor of Alabama in 1853. He stayed in the U.S. Army until the secession crisis, then resigned his commission and took charge of the Confederate Ordnance Department, at the rank of major, on April 8, 1861. He headed the department throughout the conflict and ended his service as a brigadier general. Among the Confederacy’s logistical high command, Gorgas earned a reputation strikingly at odds with that of Lucius B. Northrop, the widely loathed commissary general, and to a lesser degree that of Quartermaster General Abraham Myers, whose place the able Alexander R. Lawton took in the fall of 1863.

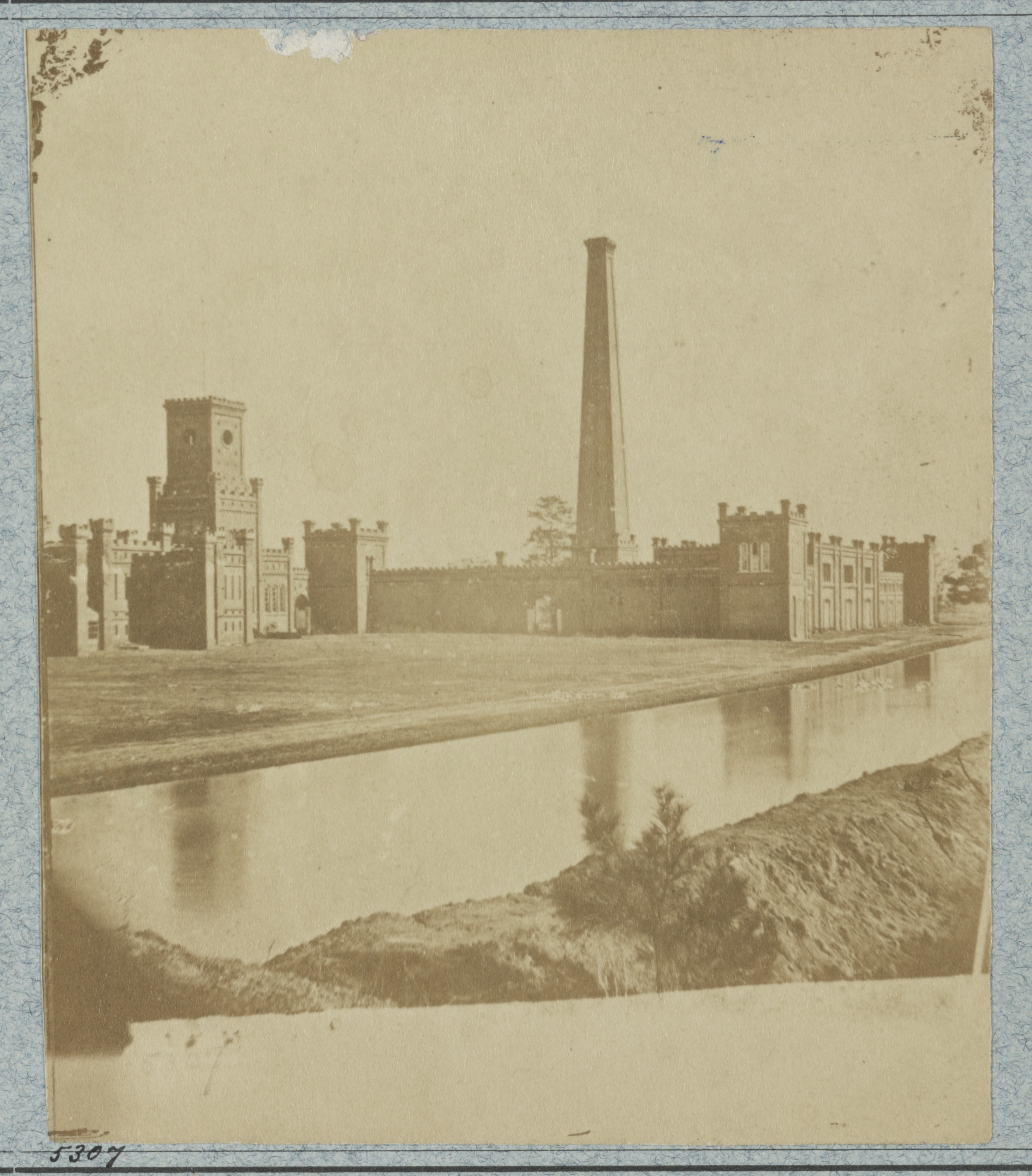

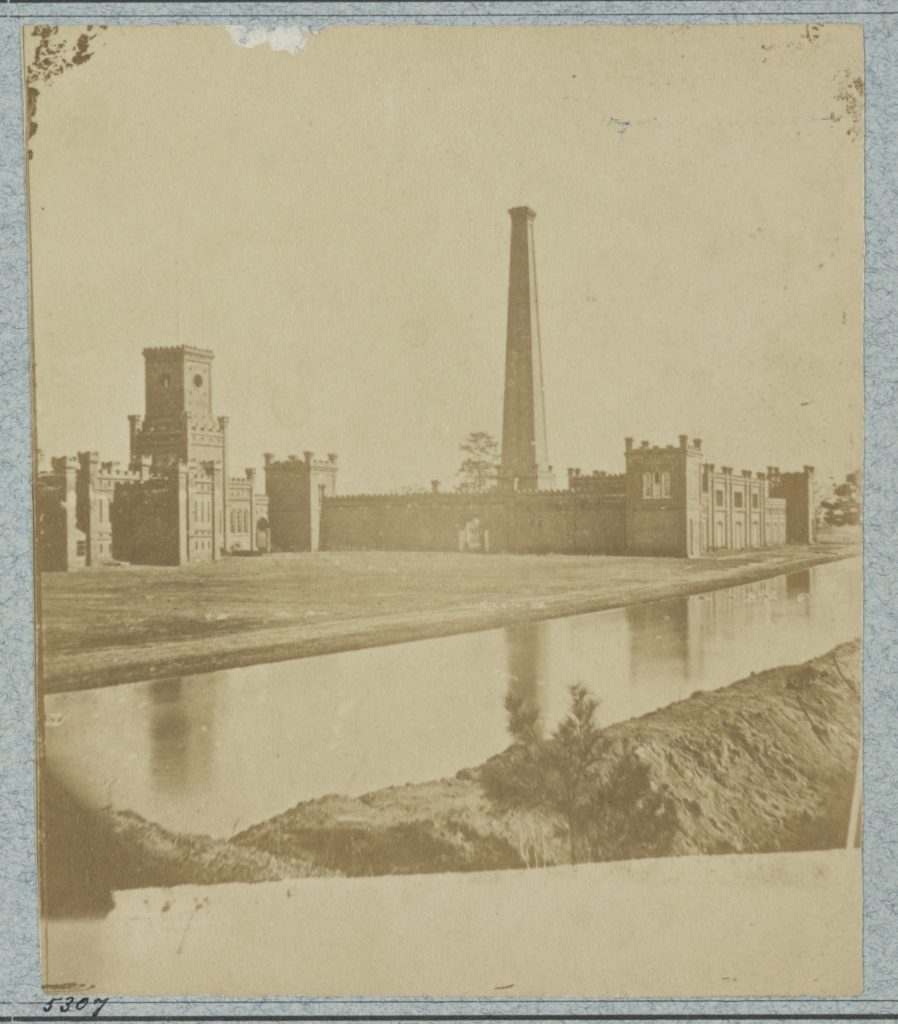

Gorgas kept a journal for more than 30 years, the Civil War portion of which Frank E. Vandiver edited for publication in 1947. The Civil War Diary of General Josiah Gorgas contains insights into the development of Confederate ordnance as well as a wealth of commentary about events and leaders. Three years into the war, Gorgas recorded a useful summary of his work in the Ordnance Department. “I have succeeded beyond my utmost expectations,” he wrote on April 8, 1864: “From being the worst supplied of the Bureaus of the War Department it is now the best.” He mentioned large arsenals in Richmond, Charleston, Selma, and elsewhere, a “superb powder mill…at Augusta [Ga.], the credit of which is due to Col. G.W. Rains,” as well as smelting works, cannon foundries, armories, leather works, laboratories, and other installations. “Where three years ago we were not making a gun, a pistol nor a sabre, no shot nor shell (except at the Tredegar Works)—a pound of powder—we now make all these in quantities to meet the demands of our large armies.” His tireless labors, concluded Gorgas with understatement, “have not been passed in vain.” General Joseph E. Johnston would have agreed with this sentiment. In the spring of 1864, he gushed that “the efficient head of the Ordnance Department has never permitted us to want any thing that could reasonably be expected from him.”

Interacting regularly with the top Rebel leaders, Gorgas frequently commented about them. His diary charts the growing importance of Lee and his army as national rallying points across the Confederacy. By the last winter of the conflict, even members of Congress seemed willing to convey great power to Lee. “There is deep feeling in Congress at the conduct of our military affairs,” Gorgas wrote with William T. Sherman’s capture of Savannah, Ga., and John Bell Hood’s fiasco in Tennessee fresh in mind: “They demand that Gen. Lee shall be made Generalissimo to command all our armies—not constructively and ‘under the President’—but shall have full control of all military operations and be held responsible for them.” Gorgas thought Hood’s campaign “completely upset the little confidence left in the President’s ability to conduct campaigns—a criticism I fear I have made long ago.”

Gorgas retained expectations of possible victory until the final stage of the conflict. Although Lincoln’s re-election “by overwhelming majorities” in November 1864 proved the folly “of disguising the fact that our subjugation is popular at the North,” Gorgas envisioned continued resistance. The Confederacy should apply military pressure until hope for victory among the northern populace “is crushed out and replaced by desire for peace at any cost.” In late January 1865, he confessed having fallen into a “momentary depression.” But his attitude changed “when I think of the brave army in front of us, sixty thousand strong. As long as Lee’s army remains intact there is no cause for despondency….We must sustain and strengthen this army, that is the business before us.”

The possible effects of emancipation drew Gorgas’ attention in 1862 and 1864. News of Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation in the aftermath of Antietam elicited three brief sentences. “Lincoln has issued his proclamation liberating the slaves in all rebellious states after the 1st of January next,” noted Gorgas matter-of-factly: “It is a document only to be noticed as showing the drift of opinion in the northern Government. It is opposed by many there.” Two years later, with large numbers of black men enrolled in U.S.Colored Troops units, Confederates discussed the possibility of freeing and arming some slaves. The absence of sufficient white manpower, insisted Gorgas, demanded enrollment of African Americans in the Confederate Army. It came down to a question of priorities—protecting slavery as it existed or accepting change in pursuit of Confederate nationhood. “The time is coming now,” he averred on September 25, 1864, “when it will be necessary to put our Slaves into the field and let them fight for their freedom, in other words give up a part of the institution to save the country, or the whole if necessary to win independence.”

Gorgas moved southward with Jefferson Davis’ party after the fall of Richmond, learning of Johnston’s surrender to Sherman at Durham Station. On May 4, he unburdened himself: “The calamity which has fallen upon us in the total destruction of our government is of a character so overwhelming that I am as yet unable to comprehend it. I am as one walking in a dream, and expecting to awake.” Eight days later, in Washington, Ga., Gorgas’ war closed. “We got paroles for ourselves…” began the last sentence of his diary.