Outnumbered rebels staged a desperate defense at Petersburg’s fort Gregg on April 2, 1865

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n the evening of April 1, 1865, battleworn Tar Heels of Brig. Gen. James Lane’s Brigade and Georgians of Brig. Gen. Edward Thomas’ Brigade stood 5 to 10 paces apart to cover General Robert E. Lee’s depleted outer defense line southwest of Petersburg. The two brigades belonged to Maj. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s Division. Their swampy, wooded position was part of Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Third Corps sector. At about 10 p.m. the ground shook as Union artillery unleashed a tremendous fusillade designed to soften up the Confederate defenses. Confederate cannons roared to life in response. Under the cover of shrieking shells, 14,000 Federal soldiers in Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright’s VI Corps sneaked forward from their main line, located between Union Forts Welch and Fisher. As they approached their picket line, the soldiers dropped to the cold ground and awaited the inevitable orders to attack the Confederate position only a short distance away. Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant believed a massive infantry assault along the entire Petersburg line would quickly locate Lee’s weak points, and many of his men knew this attack represented their best hope to end the war in the Eastern Theater. These soldiers also realized what an assault against the heavily fortified Rebel works really meant—many of them would not live to see their next meal. The artillery barrage stopped, and an eerie stillness fell over the lines.

At 4:40 a.m., a lone blast from a cannon manned by the 3rd Vermont Light Artillery signaled the attack. Chilled and shivering Union soldiers pushed themselves off the ground and moved toward the Confederate line. Their predawn thrust quickly shattered the North Carolina position. Exuberant Union infantrymen rolled east into the Georgia flank. Private John Andrews, 14th Georgia, described the difficult scene at first light: “The whole country was blue with them as far as we could see and I lost hope right then and there.” Fear-stricken Georgians and North Carolinians bolted toward Fort Gregg.

Union prisoner details escorted captured Confederates away while the remaining VI Corps troops replenished their cartridge boxes. Most of Wright’s Federals then turned southwest, away from Petersburg, and moved along the outer Confederate line toward Hatcher’s Run to mop up remaining Rebel units. This development would later give Wilcox time to unscramble the chaos and launch a counterattack from the Fort Gregg area.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Confederate officers raced about trying to rally their demoralized men[/quote]

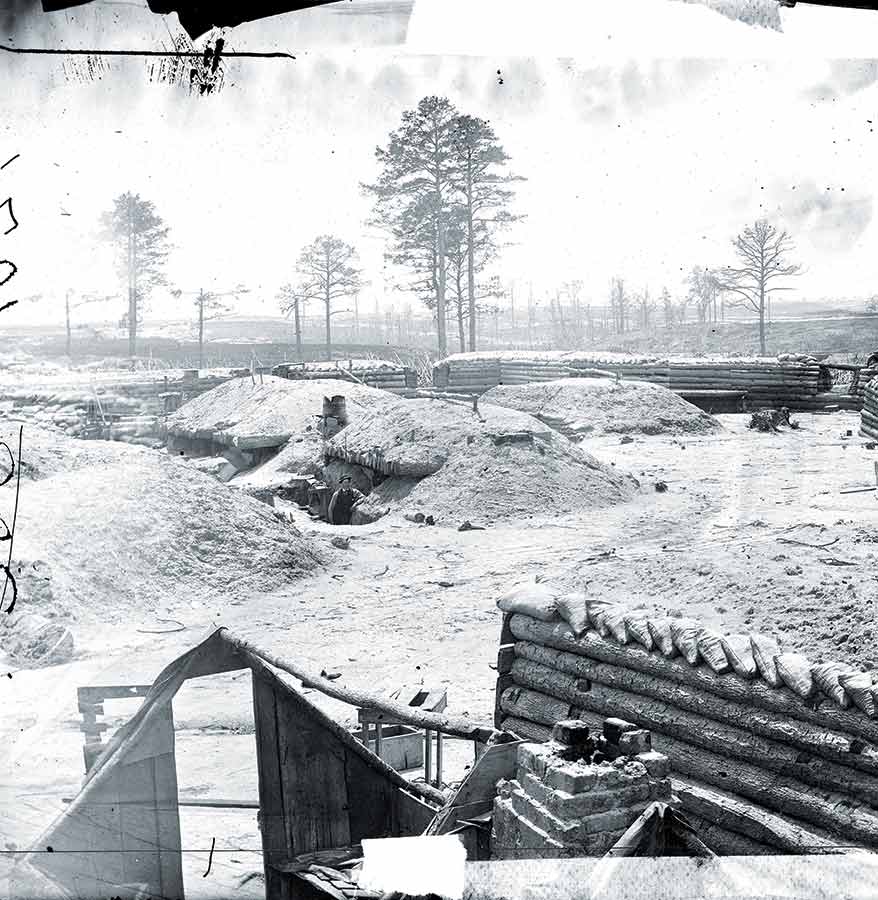

A chaotic scene surrounded Fort Gregg as Confederate officers raced about trying to rally their demoralized men. Another bastion, Fort Whitworth, sat about 600 yards north of Gregg. Both stood atop a ridge about 2½ miles west of Petersburg and just north of the Boydton Plank Road. The crescent-shaped Fort Gregg faced south overlooking the road. The steep-angled earthen walls of Gregg towered 15 feet over a rain-filled moat. The ground beyond the moat gently sloped down to the Boydton Plank Road. An unfinished trench jutted away from the northwest parapet but ended after only 30 yards. Engineers had planned to run this trench all the way to Fort Whitworth.

Confederate engineers had built both forts in October 1864. The sister forts’ purpose was simple: to protect the inner Confederate line, one mile east of the forts, in the event that the outer line was broken. The inner line was referred to as the Dimmock Line because Confederate engineer Captain Charles H. Dimmock had led the 1862 effort to ring Petersburg with a stout defensive line interspersed with numerous artillery redoubts.

When General Wilcox arrived at Fort Gregg he found Lane and Thomas and ordered them to assemble their brigades to launch a counterattack to reclaim some of the lost outer line. Lane was incredulous and disagreed with the plan. “I was opposed to a forward movement, and wanted to abandon the detached forts [Gregg and Whitworth] and fall back at once to the interior lines.”

Wilcox overrode Lane’s objections. Lane also strongly disagreed with the last part of Wilcox’s order, which would have serious consequences for soldiers from both sides. Wilcox told Lane that when he was forced to fall back, his men should retire to occupy the ramparts of Fort Gregg. Lane knew this would be a death sentence for his men.

A short time later, some 600 men from the North Carolina and Georgia brigades formed into line of battle west of Fort Gregg and marched southwest toward a collision with the oncoming Union XXIV Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Gibbon.

Soldiers from Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Harris’ Mississippi brigade soon arrived at Fort Gregg to aid the piecemeal defense. The Mississippians had received an emergency summons at 1 a.m. while manning their own lines at Bermuda Hundred. Harris had hustled his men toward Petersburg and the growing sound of guns. Shortly after leading his men across the Appomattox River, Harris received orders from General Lee “to report to Gen Wilcox, near the ‘Newman House’ on the Boydton plank road.”

The Mississippi brigadier led 400 men from the 12th, 16th, 19th and 48th Mississippi Infantry at the double quick southwest toward the Newman House, which stood just west of Fort Gregg. Harris rode ahead and found Wilcox, who ordered the Mississippians to catch up and form on the right flank of the Georgia–North Carolina counterattack line. Wilcox urged Harris not to allow his men to become engaged, but simply “to delay the forward movement of the enemy as much as possible” to buy time for reinforcements from Maj. Gen. Charles Fields’ Division en route from Richmond.

A short time later, the Confederate counterattackers bumped into the lead elements of General Gibbon’s corps. Gibbon’s men had spent the previous few days manning Union lines near Hatcher’s Run. Just before 7 a.m. orders reached the former Iron Brigade commander instructing him to move his two divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. Robert S. Foster and John W. Turner northeast toward Petersburg to assist the VI Corps.

The men in the undermanned counterattack soon retreated in the face of Gibbon’s overwhelming force, and hustled back toward Fort Gregg. Frustrated Confederate officers tried to rally the men at Fort Gregg, but many disgruntled Rebels kept moving toward the relative safety of the inner line and the beckoning Petersburg church spires farther to the east.

Many of the Southerners, however, did enter the sally port along the wooden rear palisade wall of Fort Gregg. These men dragged extra ammunition and weapons to their firing positions along the parapets. Two artillery crews from the 4th Maryland Artillery and the Washington Artillery added some needed firepower. Best estimates placed the Fort Gregg garrison at just more than 300 men. Lieutenant Colonel James H. Duncan, 19th Mississippi, soon arrived there to be the senior Confederate officer. About 150 men in the 12th and 16th Mississippi regiments entered the small fort and manned the rear and northwest wall. They joined about 80 North Carolinians mostly from the 33rd and 37th Infantry and about 40 more men from the 14th, 35th, 45th and 49th Georgia. Another handful of Confederate artillerists armed with rifles rounded out the Fort Gregg garrison. They would soon face nearly 5,000 soldiers from five Union brigades.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Best estimates placed the Fort Gregg garrison at just more than 300 men[/quote]

General Wilcox rode into the fort to rally the men and told them that they held the safety of Lee’s army in their hands and urged them to hold to the last man. Their gift of time would allow reinforcements to reach Petersburg. Wilcox and his small staff then departed Fort Gregg. Members of the garrison turned their attention to the southwest.

Some 800 yards away, several blue battle lines stretched toward the horizon. Sunlight glinted off thousands of bayonets as the various regiments maneuvered into position to attack Fort Gregg. The Federal infantrymen nervously waited for their own artillery fire to stop and the inevitable orders to charge.

Two Union brigades, commanded by Colonels Thomas O. Osborn and George B. Dandy, stood in the first line. Osborn’s men waited about 500 yards south of Fort Gregg on a hill occupied by Fort Owen and the outer Confederate line. The 199th Pennsylvania, 67th Ohio and 39th Illinois lined up in a gentle arc from right to left. The 62nd Ohio stood just to their front in a skirmish line. A small contingent from the 85th Pennsylvanian squeezed into the line between the 67th Ohio and the 39th Illinois. Dandy’s 3rd Brigade soldiers connected the arc on the left of the 39th Illinois with the 10th Connecticut and the 100th New York in order. Sergeant Michael Wetzel of the 39th Illinois later recalled, “The fort [Gregg] was as full of men as ever a dog was of fleas.”

At about 1 p.m., thousands of Union soldiers stepped from the wood line. As the enemy came into range, Confederate small arms fire accompanied by canister belched forth. Longer-range Rebel artillery at Battery 45 enfiladed the blue infantry when it reached the Boydton Plank Road. Through the sheer weight of numbers, the Union line continued forward and those first soldiers who approached the fort discovered the moat filled with waist-to-shoulder-deep water. They sloshed into the water and clawed and scaled Fort Gregg’s walls. One Georgian remembered the first Yank he was sure he killed. “I got ready to shoot through a port hole and as I raised my gun to shoot a Yank stuck his face in the hole. I fired in his face and he fell.”

A Brave, Lucky Tar Heel

Color corporal James W. Atkinson of the 33rd North Carolina took advantage of the chaos as Union troops entered Fort Gregg. The 20-year-old soldier, wounded an incredible five times during the war, clutched the staff of his beloved battle flag, dropped his musket and made his escape. Once clear of the fort, he sprinted with his colors toward the safety of the inner line. Several Federal soldiers noticed Atkinson’s bold flight and yelled at him to halt. Their bullets soon followed his trail. Two gave chase, but they halted when several artillery shells from Battery 45 landed nearby. Atkinson, with his chest heaving, then stopped and looked back toward Fort Gregg. He defiantly waved the 33rd North Carolina’s flag back and forth over his head. More bullets flew toward him as he shouted obscenities at the Yankees, but a roar of support erupted from the Southerners along the inner line for the brave corporal who somehow made good his escape—unscratched. J.J.F.

Exhausted Federal troops stuck bayonets into the walls for footholds so they could clamber upward. Some soldiers climbed up the backs of their comrades to try to reach the top. The 199th Pennsylvania’s adjutant Lieutenant Horace Evans grimly recalled, “The men all the time dropping down dead into the ditch as the brave fellows would mount the parapet and try to get inside the fort.”

The 199th, on the right flank, suffered the second highest number of Union casualties for the day with 16 killed and 65 wounded. The young commander of the 100th New York, Major James H. Dandy, brother of the brigade commander, died as he led his men across the unfinished trench toward the fort’s rear. Lieutenant Colonel Ellsworth D.S. Goodyear, commanding the 10th Connecticut, fell in front of the moat with two severe wounds. The wounded Goodyear recalled: “Now commenced one of the savagest hand to hand, muzzle to muzzle, fights, which it was my lot to witness during the war.” Union officers screamed for reinforcements as the Confederate guns from Forts Gregg, Whitworth and Battery 45 pinned down some 2,000 Union soldiers in the first attack wave.

Soon Colonel Harrison Fairchild received orders to send his brigade into the fray. The 89th New York moved forward, followed by the 158th New York on their left flank. They rushed ahead in a second attack wave toward Fort Gregg’s west wall. Soon after beginning this charge, Major Frank Tremain fell dead at the head of the 89th New York. The New Yorkers stormed on over the connecting trench toward the northwest parapet wall. Several officers led their men to the fort’s rear palisade wall constructed of thick pine logs. The 158th New York lost three of its color corporals in this area.

A third line of Union infantry entered the fray. Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Potter maneuvered his brigade, composed of the 116th Ohio and 34th Massachusetts, to hit the fort from the south. The other brigade, commanded by Colonel William B. Curtis, moved on Potter’s left flank. This brigade comprised the 12th West Virginia, 54th Pennsylvania and 23rd Illinois.

Sergeant James P. Ryan, the 54th Pennsylvania’s color sergeant, fell dead as he planted his flag on the parapet. Major Nathan Davis, also of the 54th Pennsylvania, received severe wounds in the charge, but he refused to leave his men. Confederate fire finally killed Davis as he struggled across the top of the wall. Lieutenant Joseph Caldwell, 12th West Virginia, was the third member of his regiment to die with the unit’s flagstaff clutched in his hands atop the wall. The West Virginia banner then fell over inside the fort.

A huge melee erupted atop the southwest wall as Lieutenant Josiah Curtis, Corporal Andrew Apple and Private Joseph McCauslin jumped into a group of Confederates to retrieve their flag. These three West Virginians hauled the flag away and replanted it on the wall. They later received the Medal of Honor for their bravery.

The numerous reinforcements Gibbon called on to aid the attack were a luxury the defenders inside Fort Gregg lacked. Wounded Confederates loaded rifles and passed them to their colleagues. Only one cannon now remained operable as the small crew from the Washington Artillery worked with precision. About 2:45 p.m., after nearly two hours of fighting, the almost-empty Confederate ammunition boxes signaled another problem for the stubborn defenders. The unequal balance finally tilted toward the Federals.

Angry Union soldiers broke open the sally port along the north side. Throngs of Northerners poured through the opening while others swarmed over the walls. Twenty-five more minutes of the most desperate kind of fighting ensued.

An unforgettable scene greeted the Union soldiers who entered Fort Gregg—bodies and pools of blood everywhere. These weary attackers from 15 regiments must have wondered how much more fight the Southern survivors could give, because they encountered a stiff resolve among most of the cornered defenders.

A Statistic

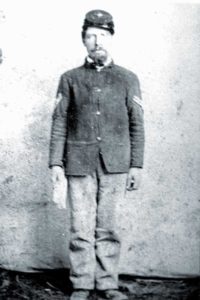

Corporal David M. Jones attacked Fort Gregg with the rest of his comrades in the 199th Pennsylvania and was one of the 65 men from his regiment wounded in the attack. He was lucky, however, that he wasn’t one of the 16 Keystoners killed as “canister, shot, and minie bullets tore through the ranks,” recalled Colonel James C. Briscoe. Jones probably wears a heart-shaped XXIV Corps badge on his hat.

Sergeant James Howard, 158th New York, grabbed the flagstaff out of the dying hands of the third color-bearer shot down that day. He planted the staff on the parapet. The wooden pole immediately splintered—shot in half. Howard snatched the stub to keep the flag up. He later received the Medal of Honor for his efforts.

Amid the chaos, Fort Gregg’s south-wall gun crew continued to ram double charges of canister into the muzzle of their cannon. Twenty-one-year-old Private Lawrence Berry held one end of the lanyard in his sweaty, dirt-caked hands. Suddenly a group of Union soldiers appeared upon the parapet, leveled their guns at Berry and shouted, “Don’t fire that gun; drop the lanyard or we’ll shoot!” Berry hollered back, “Shoot and be damned!,” and yanked the lanyard. Every Yankee in front of the gun was swept off the wall by the blast. Berry then fell dead, shot numerous times.

Mississippi Captain Archibald Jones believed the nastiness at Fort Gregg surpassed his experience a year before at Spotsylvania’s Bloody Angle. He gave a grim description of the ghastly stage that greeted the final Union charge: “The noise outside was fearful, frightful and indescribable, the curses and groaning of frenzied men could be heard over and above the din of our musketry. Savage men, ravenous beasts.”

Pockets of Rebels, faced with the inevitable, finally held their hands up to surrender. Some exasperated Union infantrymen began shooting and bayoneting the Confederate survivors on the spot. Union officers fired into the air or threatened their own men to stop them. The 16th Mississippi’s Franklin Riley recalled, “Had it not been for the Union Officers, so angry were their soldiers, most of us would have been killed.”

Cadmus Wilcox adamantly praised the beleaguered garrison when he wrote, “The heroism displayed by the defenders of Battery Gregg has not been exaggerated by those attempting to describe it. A mere handful of men, they beat back repeatedly the overwhelming numbers assailing them on all sides.”

Shortly after 3 p.m., the surviving members of the Fort Gregg garrison had dropped their weapons. Corporal William L. Norton of the 10th Connecticut shook his head at the gruesome carnage. “Union and rebel soldiers were found dead in each other’s grasp,” he would say. “Thirteen rebels were found inside the fort killed by bayonet thrusts, and scores were wounded by the same weapon.”

Gibbon said of the attack on Fort Gregg: “This assault, certainly one of the most desperate of the war, succeeded by the obstinate courage of our troops, but at a fearful cost.” Gibbon’s men found the parapet and grounds inside Gregg littered with the dead, bloody bodies of 57 defenders and another 243 wounded. Only 33 Rebels surrendered unscathed. Another 85 defenders were killed or captured at Fort Whitworth as the 19th and 48th Mississippi regiments raced toward Petersburg as Fort Gregg felGibbon’s own casualty figures were simply staggering. He reported his losses at 122 killed with another 592 wounded; however, this number would climb to more than 800 dead and wounded as unit adjutants revised their casualty numbers.

Fort Gregg’s defenders sacrificed themselves, but they gave Lee the time for Longstreet’s reinforcements to reach Petersburg and shore up the inner line. The garrison’s desperate last stand blocked easy access to Petersburg for Grant, thus robbing him of time, energy and soldiers. Without the heroic effort, Lee might have had his army trapped inside Petersburg. The Army of Northern Virginia escaped that night under the cover of darkness. This momentary reprieve enabled Lee’s grizzled veterans to fight again until the inevitable showdown and surrender one week later at another famous Virginia site—Appomattox Court House.

Historian and author John J. Fox III lives in Winchester, Va. ngle Valley Press released his book Stuart’s Finest Hour: The Ride Around McClellan, June 1862, in 2013 and The Confederate Alamo: Bloodbath at Petersburg’s Fort Gregg on April 2, 1865, in 2010.