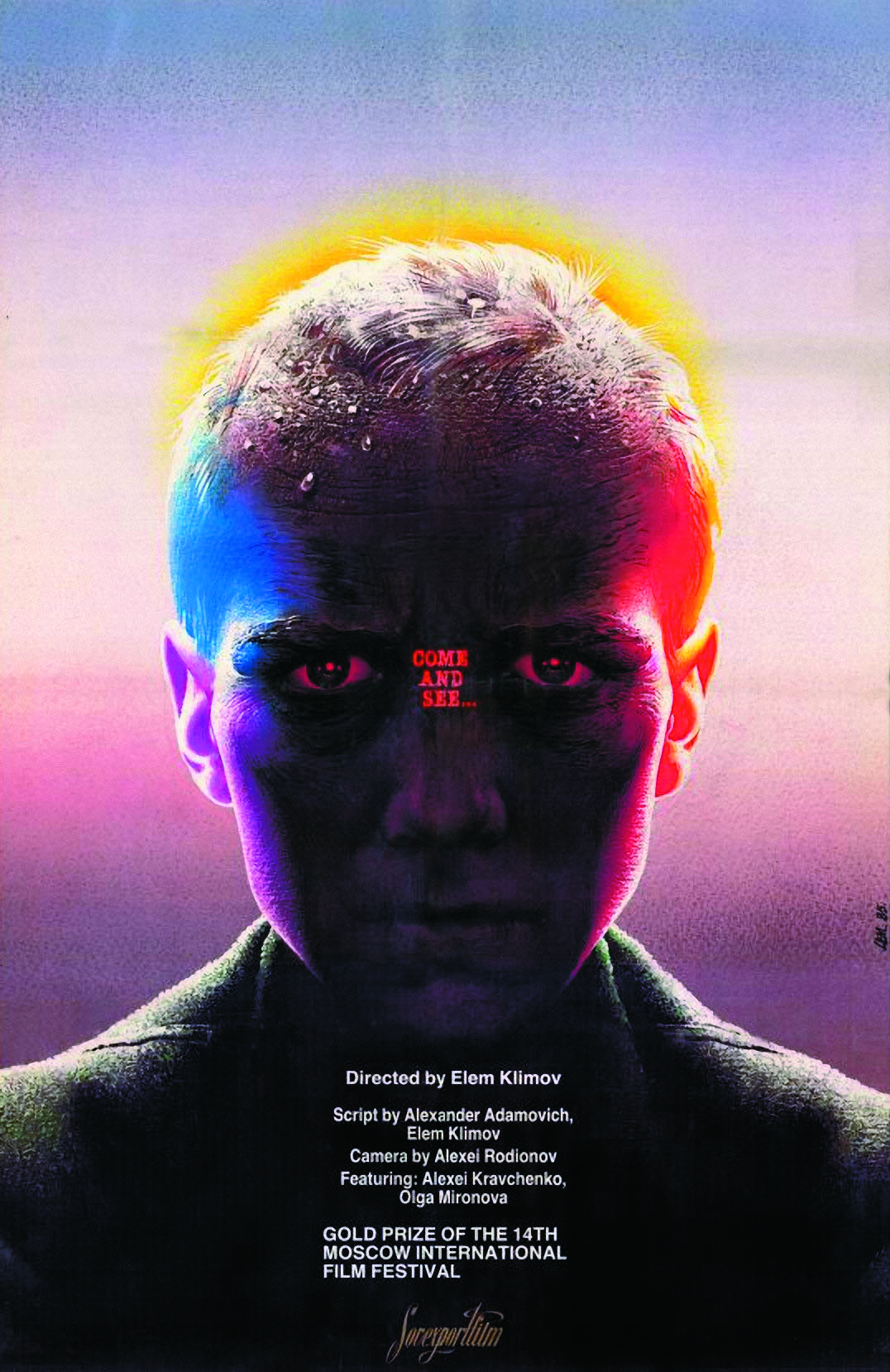

IN HIS CLASSIC 1959 book, The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle, philosopher and World War II veteran J. Glenn Gray observed that war is visually fascinating. Director François Truffaut expanded on this thought, arguing that it is impossible to make an effective antiwar movie because war by its nature is exciting, especially to the eye. Come and See, a 1985 drama set during the Great Patriotic War and directed by Elem Klimov in the Soviet Union, defies Truffaut’s dictum.

IN HIS CLASSIC 1959 book, The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle, philosopher and World War II veteran J. Glenn Gray observed that war is visually fascinating. Director François Truffaut expanded on this thought, arguing that it is impossible to make an effective antiwar movie because war by its nature is exciting, especially to the eye. Come and See, a 1985 drama set during the Great Patriotic War and directed by Elem Klimov in the Soviet Union, defies Truffaut’s dictum.

The film takes its title from the New Testament’s Book of Revelation: “…And when he had opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see. And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.”

Klimov asks, in effect, that we come and see an apocalyptic vision play out in a backwater of Nazi-occupied Belorussia, now Belarus. There, forests, fields, and hamlets constitute a hell as vivid as the one Dante Alighieri portrayed in his Inferno. Klimov succeeds, paradoxically, because he assumes no moral position but rather observes, with eyes wide open, his characters and the nightmare world in which he has placed them.

As the film begins an old man is calling to figures out of frame revealed to be two boys of 14 or so. The youths are digging in loose soil to retrieve weapons; they are intent on signing up with a band of partisans. The old man tries to discourage them, but the boys ignore him, and a few days later enlist.

From this point the film follows Florya (Aleksei Kravchenko), who has joined the resistance to take action but instead is mostly acted upon. As the partisans depart on a mission, a man with tattered footwear appropriates Florya’s boots. The fighters order the boy to remain in camp, together with Glafira (Olga Mironova), a girl not much older than he. The two, who spend much of the film together, as companions rather than friends, leave camp to wander a largely empty landscape, trying to avoid dangers both elusive and omnipresent. Florya suggests they make their way to where his mother and siblings live. No one is at the hovel, but a warm meal is in the oven. Flies are buzzing. The boy and girl begin to eat, nearly oblivious to the insects.

Deciding his family is hiding, Florya races from the hut. Glafira follows. Over her shoulder the teenager sees the source of the flies: piled against the dwelling are dozens of naked corpses, surely including Florya’s family. Glafira keeps this information to herself as she and Florya wade through a waist-deep bog to an island where the boy imagines his family to be. Finally, drenched in mud and reeking water, the girl cannot contain herself.

“No, they aren’t here!” she screams. “They’re dead!”

Furious, Florya tries to strangle Glafira. A partisan comes for the pair. He leads them to a group of refugees and resistance fighters in whose midst, lying on his back, is the man who tried to get Florya and his friend to stop digging.

Third degree burns cover the dying man’s body; the Nazi patrol that slaughtered the civilians at the hut set him on fire as a lark. “Florya,” the old man says. “Didn’t I warn you? Didn’t I tell you not to dig?” In that moment Florya finally accepts the deaths of his mother and siblings. The scene’s horror is oddly intensified by the partisans’ blatant lack of concern. One fighter has mounted a skull atop a scarecrow-like torso and laughingly applies clay to it, sculpting a facsimile of Adolf Hitler’s head.

Indifference is central to Come and See. Klimov wanted his film to have devastating impact, and he succeeded; Come and See is widely admired as a masterpiece. But he achieves this impact through studied indifference. The camera impassively regards characters and situations. The editing never emphasizes agony, atrocity, or terror. The soundtrack, understated and monotonously ominous, conveys neither empathy nor antipathy.

A viewer may see good and evil, but every element in the film conspires to deny that good and evil exist. In a harrowing sequence, Germans—who with one minor exception do not appear until 90 minutes into the two-and-a-half hour film—round up Florya and residents of a village and crowd them into a barn. An SS officer announces that children must stay, but anyone without children can climb out through a window. Only Florya accepts the cruel offer. Moments later a young mother attempts to leave with her toddler. The soldiers toss the little one back inside, drag the woman away by her hair, and torch the barn. As the screaming starts, the soldiers applaud. For a full 10 minutes the camera holds on the barn and the sheets of flame consuming it, cutting away only to show soldiers carrying off the terrified young mother to be raped and their comrades forcing Florya to his knees and putting a pistol to his temple—not to kill him, but to use him as a prop for a jovial group snapshot.

In its closing moments the film at last adopts a moral position. The camera shows justice being meted out. The muted soundtrack swells in tragedy. The wretched partisans acquire nobility. And the ineffectual Florya suddenly performs an act of stunning albeit only symbolic power. There is no redemption.

“The spirit gone, man is garbage,” Joseph Heller wrote in Catch-22.

In war, Come and See declares, the living are garbage, too.

Originally published in the January/February 2015 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.