Reconnaissance aircraft had spotted a strong Viet Cong force dug in and ready to defend a weapons cache near Saigon. Our unit’s mission was to destroy it.

A couple of days after the start of the 1968 Tet Offensive, my company climbed aboard assault ships and took off from the helipad at Cu Chi, headed for the field. Looking down, we saw smoke lifting from fire zones. Some areas, covered with shell holes, looked like the craters of the moon.

After landing, my unit—C Company, 1st Battalion, 27th Regiment (1-27), 25th Infantry Division—dug in a perimeter, blowing bunker holes with explosives. Vietnamese came nearby, carrying baskets of soda on ice. “GI numbah one,” they said. “VC numbah ten.”

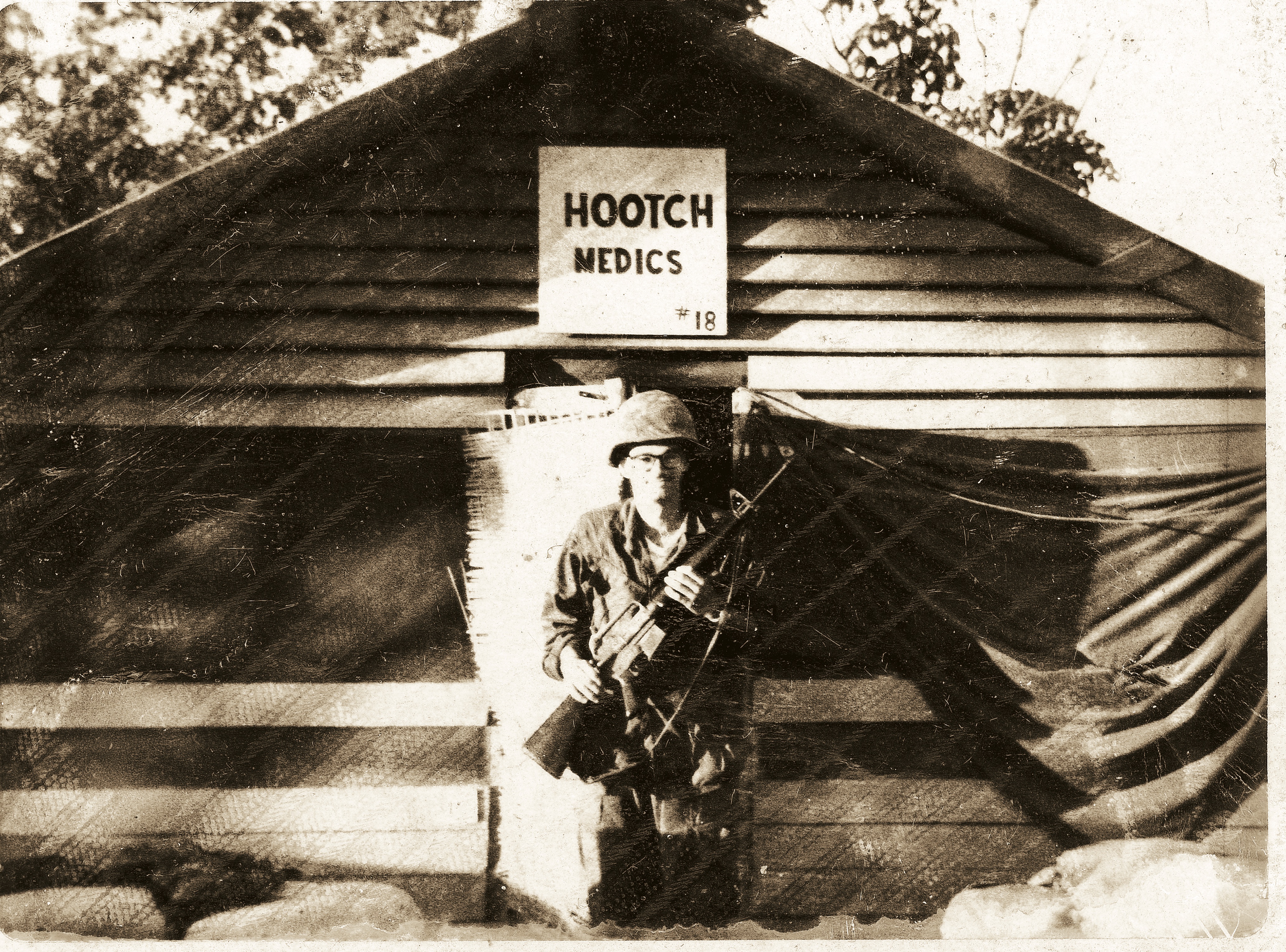

I walked over to them with a smile and bought some Coca-Cola, using Vietnamese piasters. We spent the rest of the day lounging at our bunkers, getting a dark suntan. Along with the other combat medics, I was there to treat the injured and sick. I bandaged a soldier’s sprained ankle. We handed out pills for colds and administered shots for VD. The only excitement of that day resulted when one of the GIs accidentally pulled the pin of a hand grenade.

The next morning there was a sudden change in operations. We hastily tore down our camp and left by helicopters, landing again in a large, grassy field on the outskirts of Saigon, where we patrolled through the surrounding hamlets to secure the area. The rows of palms had leaves that bowed down and knifed upward. Green limes covered the bushes. Papaya plants were ripe, growing among the hooch complexes. We stole fruit from a yard and ate it as we moved on.

The Vietnamese seemed carefree. The old men worked behind their water buffaloes, and half-naked children played in the road. The women were fixing dinners and nursing their children. Our new position was a large field in a jungle clearing, which we shared with armored vehicles of the 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry. The infantrymen dug in along the paddy dikes. Joining them, we excavated a new bunker. I dug and shoveled until dark, making an emplacement we would never get to sleep in. The enemy was coming in too fast for us to stay in one location.

Lieutenant Charles S. Stewart brought us over to the command post. “Things are going to get rough,” he said. “The VC are setting up their biggest offensive around Saigon. The next few weeks will determine the outcome of the war.” The lieutenant grimaced, showing the strain of weeks of hard combat. His face was unshaven, and he began to tremble. He had fought through many hard battles that week and was an extremely tough and brave fighting man.

That night we all watched with utmost caution. We traded radio checks behind the dike and surveyed the dark jungle. Sometime after midnight, an ambush patrol cut loose with heavy gunfire. AK-47 rounds soared over our heads for hours. Charlie was getting ready to strike.

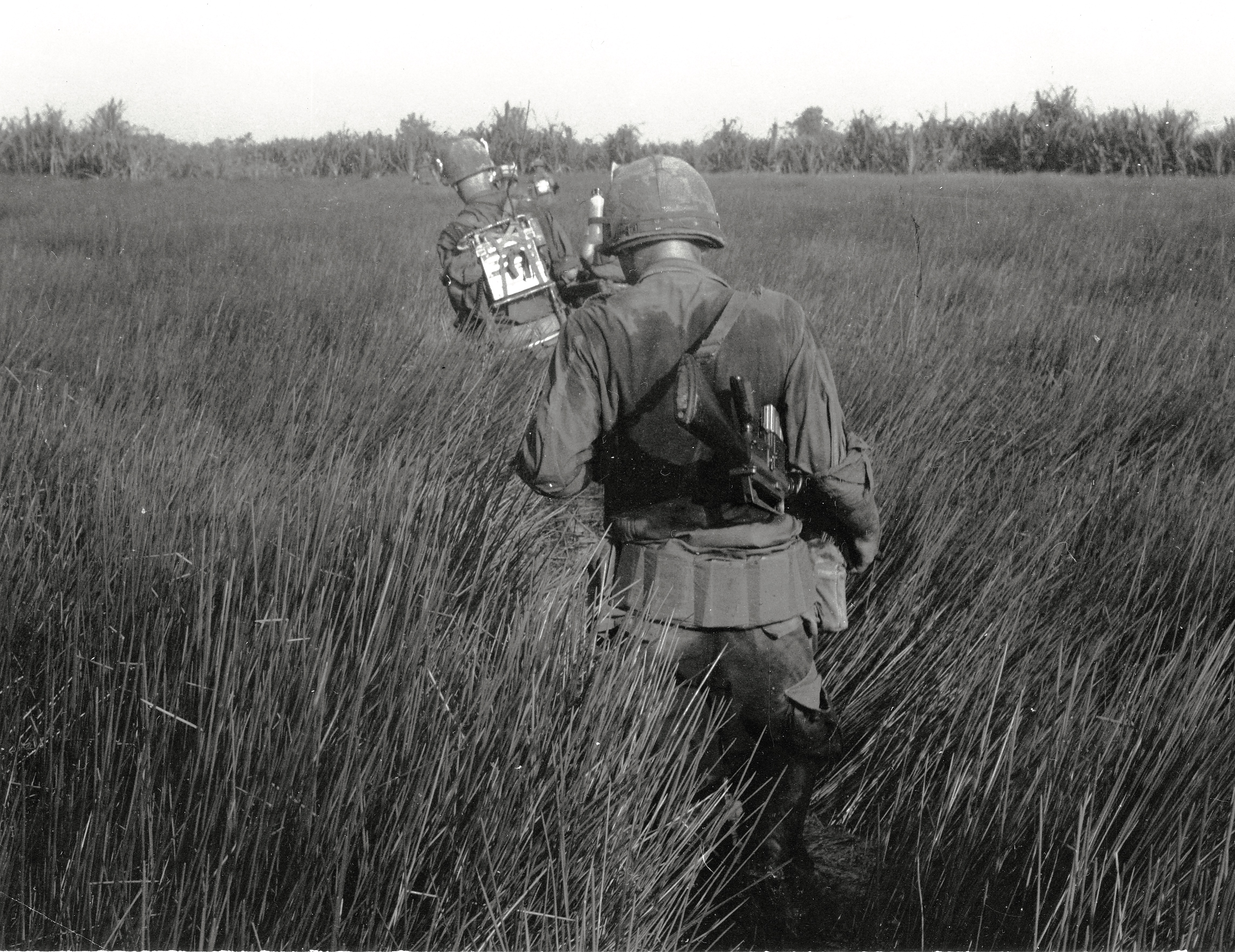

In the morning our company got ready to execute a blocking force mission: to cut off the VC being pushed toward us by an Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) unit. It was supposed to be a classic hammer-and-anvil operation. Choppers were also going to attack a village where suspected VC were hiding. The idea was to scare the enemy troops toward our blocking force. We began a slow march in full battle gear. We carried ammo bandoliers, and our belts were lined with fragmentation grenades. We also carried M-16s, and some of us had M-72 light antitank weapons. Others carried M-60 machine guns and long belts of linked ammo. We watched for the suspected VC bunkers and trench lines. All the while the local Vietnamese worked and played among their farm hooches. Aircraft overhead dropped leaflets and loudly broadcast propaganda.

Our company came through the village of Hoc Mon in two columns. The Vietnamese civilians milled around and generally ignored us. Thatched hovels were in rows on each side looking quaint and primitive. In a baked clay hooch yard, I found a strange exotic fruit. It was as large as a volleyball with sweet, pulpy sections. I ate some, finding them delicious. “What kind of fruit is this?” I asked Lieutenant Stewart.

“That’s a grapefruit,” he said. “It’s larger because it’s been ripened on the tree.” The lieutenant had recovered somewhat from his stress, after taking his first bath in days. The supply unit probably had given him new jungle fatigues too.

We reached the edge of town by a large, watery rice paddy. Some ARVN soldiers emerged from a walled compound. They laughed, skipped around and smiled. In chattering Vietnamese, they were saying that ARVN infantry elements were in a firefight in the woods against the VC.

Suddenly, a helicopter burst out of the clouds firing its machine gun. The rounds splattered dirt and peppered down the road ahead. The chopper flew straight through the city, strafing the people.The fire brought the townspeople running out in confusion. They hurried down the road driving taxis and ox carts, and the injured were rushed to hospitals in Saigon.

C Company began to establish the blocking force. The chopper attack apparently was a tactical action to flush any hiding VC into our waiting guns. Meanwhile, we entered a lush banana field and palm grove.

We were then given positions along the road. My place was in a dirty pigpen beside grunting sows. Aiming my M-16 through the fence, I watched across the road at the opposite rice paddy, looking for any movement.

The Vietnamese civilians were waking up to the fact that danger was near. All afternoon they wandered up and down the roads, leading water buffalo and carrying their belongings. Small Vietnamese children led water buffalo and ox carts. Many GIs were astounded that the beasts would follow a child obediently but would attack an infantryman viciously. Something about the soldiers must have terrorized them. I was nearly trampled by one.

Soon, lines of battle-fatigued ARVN soldiers came down the dirt road, hanging their heads. They were dressed in U.S. jungle fatigues and helmets, and carried Browning automatic rifles, Thompson submachine guns, carbines and M-16s. A bloody ox cart bore the wounded. Tears streamed down the soldiers’ faces as they cried out and howled in grief. I was impressed at the ARVNs’ deep feelings for their fellow soldiers.

Again we moved out on patrol, sweeping through the rice paddies. In some hilly grasslands, VC rounds cracked over our heads. We lay on the ground watching diligently. Some GIs arrived guarding 10 captive Vietnamese. They were young, scrawny kids who looked about 15, wearing T-shirts and shorts. A husky noncommissioned officer kept watch on them with an M-16. The sergeant acted as if he meant business. The prisoners, however, appeared happy and undaunted by their capture.

As rounds came overhead, I ducked behind a paddy dike in the dirt. Specialist 4 Francis Kairaitis, a grenadier, came up to me. “Get up, Doc,” he said. Regaining confidence, I stood up. He was a point man and an impressively courageous, unyielding soldier. His sheer presence in combat reminded me of Alexander the Great. We shivered all night, lying on the hard ground. At dawn we moved out again. In late afternoon, we finally stopped in a field beside a lonely hooch complex. We were worn out, dusty and hot. Tiny ants crawled all over our bodies. Mosquitoes bit with no mercy. We slathered on insect repellent from the bottles we kept in our helmet bands. Again we were forced to lie all night on the rock-hard ground.

The next day we got a break. GIs wrote home and dumped well water over themselves. The mail chopper came in, and we were handed out letters. At dark, helicopters brought in hot chow. The medics passed out malaria pills. Morale got a little better, but Charlie still waited. He fired a couple of harassment rounds into our perimeter before sundown. From inside the perimeter, patrols moved out to take up their night listening and observation posts.

After dark we prepared to mount a night ambush patrol. We put on our gear and began to march down the rice paddy dikes. Kairaitis gave me a bag of Claymore mines to carry. Lugging the heavy sack, I soon fell behind the rest. To my dismay, the sack slipped from my hands and fell with a plop into the rice paddy. I groped desperately through the murky water. At last, with a lucky reach, water up to my shoulder, I grasped the bag. Though a couple of mines were lost, I recovered most of them. Hurriedly I caught up to the rest of the patrol.

The 2nd Platoon set up watch on a large berm along a hedgerow of trees, a swampy area with deep paddy water. We established groups of three men—one to observe, one to monitor the radio and one to sleep. Every half-hour the positions rotated. The night started out peacefully, and all was pitch dark as we set about our duties. After the first watch I was allowed to sleep. An explosion came suddenly, a terrific blast, right on the other side of the berm. It was a fragmentation grenade. We grabbed our weapons, prepared to fight. Another explosion shook us—only a few feet away—followed by two more. I clung tightly to my weapon as we waited for orders on what to do. No word came, and the explosions ceased.

Morning arrived with a brilliant sunrise. As we grouped together to warm ourselves, we learned that one of our squad leaders had tossed the hand grenades at ripples in the paddy water. He thought they were VC slipping along the berm; it was really just the wind making waves. The explosions, however, kept us alert during the night.

In the morning we moved back to our perimeter, very exhausted. Members of the 2nd Platoon were already eating C rations; I opened my can of ham and eggs.

The company commander and lieutenants were on the other side of the paddy dike, poring over maps. Soon our new orders came over the radio. Reconnaissance aircraft had spotted a VC force dug in and ready to defend a weapons cache. Our unit’s mission was to destroy it, in order to neutralize their ability to fight. The VC force was estimated at about 1,000. We only had two companies, a little more than 200 men. We would have to depend on helicopters and armor for fire superiority.

We put on our web gear and loaded our weapons. The GIs trekked across the fields, moving in single file along a dirt road by some thatched huts. Grabbing some of the men’s canteens, I went to a well to get water. Vietnamese civilians, who would soon be inundated by the war, worked nearby. I handed the cool and dripping canteens to the soldiers.

As the patrol moved out into a large soybean field, the high-pitched crack of AK-47 fire rang out. Rounds flew over us. The men dove into the bean rows. After a while, my platoon crept out of the beans and silently moved along a scrubby hedgerow. The company’s command element started across the open ground, running toward a grove of trees for cover. Now the enemy opened fire heavily. Apparently they were hidden in deep trenches to the front.

Diving behind the hedgerow, I found the safest hideout. Our objective was to place the enemy in a crossfire. The command element fired from across the open field, while the 2nd Platoon fired from the hedgerow. Helicopter gunships swooped in with sudden speed and loud rocket fire. Charlie returned fire with sharp bursts aimed at the choppers. Kairaitis rose up and fired grenades over the trees at the enemy, then walked out in front of the whole melee with careless bravery, paying no attention to the withering fire around him.

Lieutenant Stewart was firing his M-16 from the hip. Machine gunners were alongside of him, firing long bursts from the tops of the paddy dikes. The VC had a .51-caliber machine gun that laid down rounds with a horrible roar. It was one of those Chinese-made contraptions and was mounted on wheels—very mobile and deadly.

The 1st and 3rd platoons had advanced close to the VC position when VC rocket-propelled grenades exploded in the bean field. They missed the GIs by about five feet.

The din rose higher and higher. Terrified, I covered my ears, hiding behind an uprooted pile of brush. The enemy fire zinged closer and closer, seeming to tear at my clothes. After what seemed like hours of trading gunfire with the VC, I received an order via the radio: “Go to the front to find the wounded.”

I took off on foot down the hedgerow and ran as fast as I could, hardly noticing the zapping bullets. As I reached the bare paddy, the fire became heavy again. I hugged the ground as if it was mama’s bosom. Kairaitis and Lieutenant Stewart were rising quickly and firing back between the incoming volleys.

I ran across the open ground. The VC somehow slacked their fire. The field became silent as both sides gathered their wounded. After treating the injured, I hid behind some brush with the company headquarters element. Some men had terrible wounds from AK-47 rounds. I dressed their wounds and gave them morphine.

Kairaitis was still standing and firing grenades at the enemy. He looked at me and smiled when I passed. “Good job, Doc,” he said. “You’re doing real good.”

The company fell back through some dusty fields. Sadly, wearily, we rested in a hooch yard. Serious looks engulfed the men’s faces. Lieutenant Hall leaned against a fence. There was a bullet hole in his steel helmet. “The Cong shot it off me,” he told us. We looked at it in awe.

The men ate their C rations and rested. The infantrymen filled their canteens and put in water purification pills. Then we had to return to the fire zone. Three dead had been left behind. Our platoons swept across the battlefield silently, crossing a cornfield with stunted ears. In the scrubby forest we found lost combat gear and scattered shell casings. The battlefield was littered with twisted shell fragments and pockmarked with shell holes. The VC were gone from the drainage trench.

The GIs lined up along the same protective features the enemy had just left. Suddenly we all let loose with a barrage of fire, a tactic to flush out the enemy. The fire raged for 20 minutes. Then we climbed over the edge of the ditch and attacked.

The VC opened fire as we advanced. Dropping among some tomato vines and pepper plants, I was nearly hit. A few GIs reached our dead. They carried the bodies back, and the whole company began to withdraw under fire. As Hueys were called in to extract us, the company sat in a paddy field and waited. I sat down to rest and promptly was covered by little crawling ants.

The next day we returned to the battle area. We hoped to find enemy weapons and more captives, but we passed through with no resistance. The VC had withdrawn. Another unit found many weapons and a Chinese .51-caliber machine gun. It was the one that had torn into us so badly the day before.

My platoon recovered several burned-out AK-47s and a few serviceable ones. Nothing reached us but sporadic small-arms fire as we passed through the hooches we had bombed so severely. We saw farmers ambling down the road beside us. Were they the VC who had fired on us the day before? We would never know.

As we returned from our special mission on the outskirts of Saigon, back to the rice paddies of Cu Chi, it was the fifth or sixth day after the start of the 1968 Tet Offensive. The chopper attack on the sleeping village seemed to me to be an atrocity of war. It may have been conceived as part of the hammer-and-anvil operation, but its only result was the capture of 10 enemy recruits.

Our ground attack on the weapons cache, however, had been a daring maneuver that succeeded in capturing a large number of weapons and the Chinese-made machine gun. We lost three killed and several badly wounded. Our tactics of crossfire and sudden attack just may have shocked the enemy into withdrawing with relatively little resistance.

James Matthews earned the Purple Heart and the Combat Medic Badge for his service in Vietnam. Today he is a research assistant who has done biological studies at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. For additional reading, see: The Tunnels of Cu Chi, by Tom Mangold and John Penycate; and The Wolfhounds, by James Matthews.

Originally published in the February 2007 issue of Vietnam Magazine. To subscribe, click here.