Perhaps the strangest love-hate relationship in the firearms business of the 19th century arose between two manufacturers with no apparent equal in their products. It came at a time when repeating arms technology was at its high-water mark. Every famed gunmaker, from Christopher Miner Spencer and B. Tyler Henry to John Browning and Arthur William Savage, was profiting from the boom. Building reputations far above their fellow competitors, Oliver Winchester and Sam Colt eventually settled into their own specialized lines of firearms.

Winchester Repeating Arms Co. got its start in the wake of the Civil War on the strength of the Henry lever-action repeating rifle, while Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Co. had spent the previous few decades dominating the sidearm market with its popular line of revolvers. By 1880 Winchester, Whitney and Marlin were producing the best-known lever-action repeaters. Within a few years, in a surprising move, Colt announced it would roll out its own lever-action repeating rifle.

The financial rationale behind Colt’s decision is unclear, as the company had achieved strong sales with its popular M1873 Single Action Army revolver and other sidearms. The driving force behind the 1883 rollout of its “New Magazine Rifle” was a patented design from noted firearms inventor Andrew Burgess. Five years earlier Burgess had designed a simple, sturdy lever-action repeater manufactured by Eli Whitney (son of the famed cotton gin inventor) and known as the Whitney-Burgess-Morse. By 1880 Whitney Arms had incorporated many of Burgess’ features into an improved Samuel V. Kennedy design, and the resulting Whitney-Kennedy lever-action repeater became the top seller of the Whitney line until that company’s bankruptcy and buyout by Winchester in 1888. The Colt Burgess incorporated further refinements from its namesake inventor.

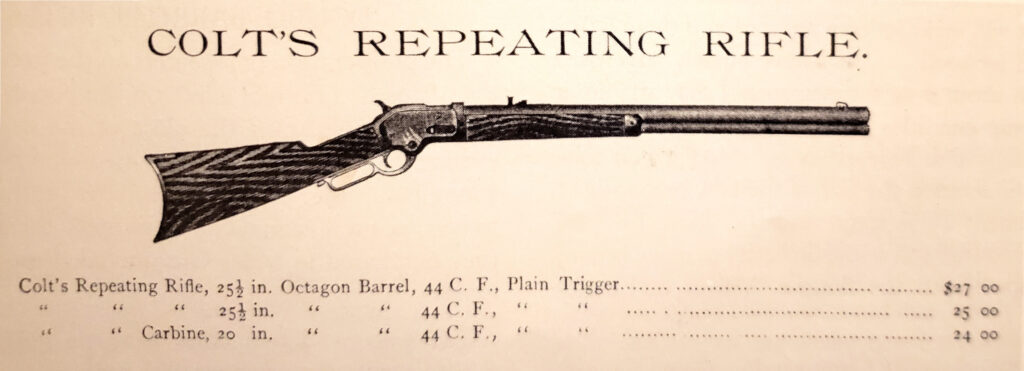

The Colt Burgess proved a thorn in Winchester’s side, as it cut into sales of the latter’s Model 1873. The Burgess employed a modified toggle-link action akin to that of the Winchester 1873, and both were chambered for the popular .44-40 Winchester centerfire cartridge. However, the Burgess was only chambered for the .44 WCF, not either of the smaller caliber cartridges also available for the Winchester ’73, namely the .38-40 and .32-20. Colt Burgess rifles were fitted with 25 ½-inch barrels, while carbines sported a 20-inch tube.

Colt announced the debut of the Burgess in a factory-issued pamphlet. The news was said to have alarmed Winchester officials to the point they immediately began work on a prototype revolver to counter the “invasion” into their turf. Such a countermove would not have been an easy venture for Winchester, as few six-guns had matched, or could match, the vaunted Colt Peacemaker.

Though Colt only manufactured the Burgess for 16 months (1883–85), the rifle did manage to reach the American West. Famed Denver firearms dealer J.P. Lower advertised the Burgess in several regional newspapers, though he apparently wasn’t convinced of the need for it. In a May 1883 letter to the Rocky Mountain News Lower noted that as the well-received, longer range .45-70 Government cartridge was easily procurable in the region, Colt should have offered its new rifle in that caliber, as had Marlin with its Model 1881 and Whitney with its Whitney-Kennedy. In other words, he believed the Winchester 1873 and other guns already available in .44-40 had fully exploited the short-range characteristics of that caliber.

Bearing the Colt name, the Burgess did have a following. In an 1887 group portrait taken in Realitas, Texas, Ernest E. Rogers poses proudly beside his mates in Company D of the Texas Rangers, a Burgess conspicuously in hand—and we know roughly what he paid for it. In 1884 the price for a Colt Burgess carbine was $24, while rifles averaged $26. Like most other contemporary gun manufacturers, Colt offered the Burgess with any special-order features or embellishments a customer might desire—naturally, for an extra cost. In July 1883 Colt presented a heavily engraved example with an octagonal barrel as a gift to Wild West showman William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who received such freebies from virtually every known gunmaker during his heyday, largely for promotional purposes.

Most Colt Burgess rifles and carbines available to collectors today are in well-used condition, those in very good plus to excellent being quite scarce. All are highly sought-after pieces, particularly the “baby carbine,” featuring a lightweight frame and barrel, which accounts for only 972 of the 6,403 Colt Burgess rifles and carbines produced. The carbine shown above (pointing left) dates from 1883, is notable for its tinned finish and shows much wear, though it remains in excellent mechanical condition.

Whether Colt’s production of the Burgess was an intentional or merely subtle threat to Winchester for some sort of behind-the-scenes corporate hokum, we may never know, but it disappeared from the Colt line almost as suddenly as it had appeared. Winchester likely breathed a sigh of relief. By then it had competition enough.