On the Trail of Colonel Walker

Research and luck reunite a revered Confederate leader’s personal effects

TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 1864—For the weary soldiers slogging it out along the Kennesaw Mountain Line, about three miles southwest of Marietta, Ga., it is the first day in nearly a week without rain. But the war—and the summer heat—continues without relief. The Union XX Corps, under Maj. Gen. “Fighting Joe” Hooker, probes the southern flank of the Confederate Army of Tennessee along the Powder Springs Road, near the log home of Peter Valentine Kolb. Coming upon the tell-tale signs of a strong enemy force in their front, the Union veterans halt and begin entrenching. But Confederate corps commander John Bell Hood, always eager for a fight, thinks he sees an opportunity to hit the Federals’ flank. He orders two divisions formed up for assault.

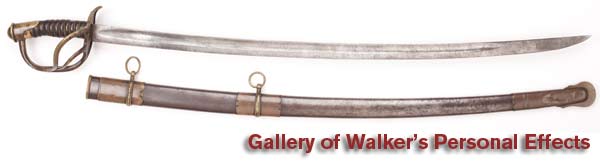

In Brig. Gen. John C. Brown’s Brigade in Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson’s Division, Hood’s orders are passed down to Colonel Calvin Harvey Walker, a 41-year-old former West Point cadet commanding the 3rdTennessee Infantry. Walker, known affectionately by his men as “Old Baldy,” and his younger brother James, who is commanding Company H, begin forming their men into line of battle. On his left hip, Colonel Walker wears a beautiful Leech & Rigdon officer’s model cavalry saber, made in Columbus, Miss., in mid-1862. Suspended from a black leather sword belt, it is secured with a Leech & Rigdon two-piece rectangular “CS” plate. On his right hip is a Colt Dragoon revolver, and in his breast pocket he carries a small New Testament, inscribed on its fly page with a list of the battles in which he has thus far fought: Perryville, Murfreesboro, Hoover’s Gap, Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, Tunnel Hill and Resaca.

It is just before 5 p.m. A Federal battery opens up on the massing Confederate divisions from a knoll about a mile in their front. Suddenly a shell explodes just in front of Walker and a jagged chunk of iron strikes the colonel directly in the face—blowing off, according to eyewitnesses, “all his head except chin and rather long whiskers.” The impact is so violent, in fact, that a fragment of Walker’s skull wounds another officer standing nearby, powerful enough that the officer has to be carried from the field. The badly shaken veterans of the 3rd Tennessee, unnerved by the gruesome death of their beloved colonel, advance into battle with heavy hearts. “Never did I see soldiers weep so over a man,” the regimental chaplain later writes. “He had been like a father to them.” The assault fails.

This is the story of the sword, belt and pocket New Testament was carrying on that fateful final day of his life.

Calvin Harvey Walker was born November 11, 1823, in Maury County, Tenn. At 16, he left home to attend the U.S. Military Academy. Walker’s tenure at West Point was brief and undistinguished; he left in 1842 with an overall ranking at the bottom of his class. In 1847, probably after graduating from Jackson College in his hometown, he received a medical degree from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. When the Civil War broke out in the spring of 1861, Walker was a prosperous, slave-owning physician and farmer living in Lynville, in Giles County, Tenn., where he was also a Mason and member of the Knights Templar. He and his wife, Helen M. Gordon, had three young sons.

On May 16, 1861, Walker began his military career as captain of a group of men from Giles County; later designated Company E of the 3rd Tennessee Infantry. After first training in Bowling Green, Ky., the 3rd was sent to Fort Donelson, a Confederate bastion defending the Cumberland River. The regiment was among the fort’s garrison to surrender to Ulysses Grant in February 1862. After enduring seven months of imprisonment, mostly at Johnson’s Island, Ohio, Walker and other veterans of the regiment were exchanged and then re-formed. Walker was elected colonel on September 26, 1862.

With Walker in command, the 3rd served in Mississippi the remainder of the year and the first half of 1863. On May 12 the regiment faced Grant’s Federals at Raymond and had 176 if its 548 soldiers cut down. “We will soon be engaged in battle,” Walker said to his men before the fighting, “and before we begin I wish to say that I do not command you to go, but to follow this old bald head of mine…”

The nickname “Old Baldy” stuck. In September 1863, the 3rd suffered heavily at the Battle of Chickamauga, with Walker among the wounded. During the fighting along the LaFayette Road south of the Brotherton Farm, Walker chided his disheartened regiment by removing his hat and calling out, “Boys, are you going to leave Old Baldy?” In an 1868 tribute Thomas H. Deavenport, the regimental chaplain, recalled that “the effect was electrical, every soldier rushed forward, everything was swept from before them. [I] must say that Colonel Walker was the most popular and successful officer in Brown’s Brigade.”

Major Flavel Barber of the 3rd grumbled in his diary, however, that Walker was “not constant and firm enough to be a good commander of a regiment. He likes the popularity and good will of the privates too well to enforce discipline.”

According to Deavenport, Walker’s attitude toward religion changed during the winter of 1863-64, when the 3rd was camped at Dalton, Ga. Walker was “an excellent physician, a cheerful, genial companion, [and] an exceedingly kindhearted man,” Deavenport noted, before adding that he was also “wicked, very profane, [and] cared but little about preaching or his Bible.” At Dalton, Deavenport said, Walker procured a Bible, joined the brigade’s Christian Association, “and was heard to swear no more.” Walker’s wife may have been influential in this conversion, as she and her husband spent time together in Cassville, Ga., during several of his furloughs that winter and spring.

During the first month and a half of the 1864 Atlanta Campaign, the 3rd saw action at Resaca and New Hope Church before Walker’s final engagement at Kolb’s Farm on June 22. The colonel’s body was initially buried south of Atlanta in Griffin, Ga., by sympathetic Tennessee ex-patriates living in the area. But in late 1865, the body was re-interred in Rose Hill Cemetery near Columbia, Tenn.

At the re-burial, Walker’s coffin was draped with the 3rd Tennessee’s battle flag, which had been secretly taken back to Tennessee after the regiment’s surrender in North Carolina in April 1865. The coffin was also accompanied by Walker’s sword, belt rig, dragoon revolver, and Bible. All were given to his widow, Helen, who subsequently donated the flag to the Tennessee Historical Society. Today it is in the Tennessee State Museum Collection. In 1897 she proudly displayed her husband’s sword with the flag at the Tennessee Centennial and International Exhibition.

Except for the flag, all the Walker artifacts remained with his direct descendants until the death of Colonel Walker’s grand-daughter. They were then inherited by Anne Lacey Dougherty-Shelton, the colonel’s grand-niece, who was married to Jack Owen “Beef” Shelton. In the 1950s or 1960s, Jack Shelton sold the sword and belt rig to renowned Atlanta collector and belt plate specialist Sydney C. Kerksis. Interested in keeping only the belt rig and its extraordinarily rare “CS” plate, Kerksis in turn sold or traded the sword to Fred Slayton of Nebo, Ky. in whose collection it remained for the next 20 years. After Slayton’s death, the sword passed through three other owners before collector Bill Beard of Monteagle, Tenn., purchased it in 2009.

When Kerksis died in 1980, Beverly M. DuBose Jr., a close friend, purchased the bulk of his collection, including Walker’s belt rig. It was among the 7,500 objects in the DuBose Collection donated to the Atlanta History Center beginning in 1985.

Jack Shelton also sold Colonel Walker’s dragoon revolver, his personal diary and a photograph of Walker and his brother. Unfortunately the current location of these artifacts is unknown. The New Testament that Walker was carrying the day he was killed was the only one of his personal effects to remain in the family, ending up in the possession of James Newton Shelton, the grandson of Anne Lacey and Jack Owen Shelton, in Homerville, Ga.

In 2009, Bill Beard discovered that Walker’s Leech & Rigdon belt was part of the Atlanta History Center’s collections and revealed that he owned the colonel’s impressive sword. A decision was quickly made to exhibit the two items together, which occurred at a February 2010 Civil War show in Dalton. That drew the attention of Civil War blogger Phil Gast.

Meanwhile, in Homerville, James Shelton’s 14-year-old daughter, Sarah, came upon Gast’s blog, “Civil War Picket,” while searching the Internet for information about her famous ancestor, Colonel Walker. Although her family still had Walker’s New Testament, Sarah knew nothing about the sword, belt rig and revolver until she spotted Gast’s blog. She quickly contacted the Atlanta History Center, and an agreement was reached to reunite Walker’s effects.

Today the sword, belt and New Testament are on display at the center, in A War in Our Backyards, the first of two special sesquicentennial exhibitions. It is the first time in 50 years these artifacts have been seen together—a very fitting tribute to a hard-fighting Tennesseean.

VISIT THE MUSEUM!

You can see Colonel Harvey Walker’s photo and personal effects at the Atlanta History Museum’s sesquicentennial exhibition “Turning Point: The American Civil War.” On permanent display at the museum in Buckhead, Ga., are more than 1,500 Northern and Southern artifacts, including cannons, uniforms, flags and much more. Highlights include the Confederate flag that flew over Atlanta during the city’s surrender in September 1864; a Union supply wagon used by General William T. Sherman’s Union army, Confederate General Patrick Cleburne’s sword; a Medal of Honor given to U.S. Colored Troops; CSS Shenandoah¹s logbooks; and medical equipment and firearms. Dioramas, videos and interactive learning stations round out the exhibition. For more information, call 404-814-4000 or visit AtlantaHistoryCenter.com.

The center’s “War in Our Backyards” exhibit will close December 31, 2012.

Bill Beard has been collecting Civil War weapons since 1949. Keith S. Bohannon teaches at the University of West Georgia in Carrolton, Ga. Gordon L. Jones is senior military curator at the Atlanta History Center.