For its faults, the Electoral College has endured because it has fulfilled its main purpose—preventing stolen elections

2020 is the 59th American presidential election year. Since the first, in 1789, every candidate has undertaken to win a majority in the Electoral College. This small body—membership is now 535 persons—materializes briefly every four years and, despite never actually meeting as a whole, almost always decides who becomes the most powerful person on the planet. Despite many a glitch, this odd institution marches on, because the Electoral College arguably fulfills the main purpose that the Framers had in mind when they created it: warding off stolen elections.

The brigands seen as most threatening at the Constitutional Convention were foreigners, and the most recent example of such thievery had involved Poland. Early modern Poland, a vast domain, stretched from Lithuania to Ukraine. This mega-state’s monarch was chosen by Poland’s nobility, assembled in the sejm or diet. When the throne became vacant in 1763, the leading candidate was the noble Stanislaw August Poniatowski. Handsome and fluent in half a dozen languages, Poniatowski, 32, would have made, according to one diplomat, an excellent master of ceremonies, though “moral courage he altogether lacks.” His main qualification was that in their twenties he and Catherine the Great, empress of Russia, had been lovers. Russia had long cultivated allies in Poland’s diet, and Catherine now used them to boost Poniatowski, calculating that he would be a compliant placeholder until she and Poland’s other neighbors—Prussia and Austria—could agree on divvying Poland up. Her ex became Stanislaw II Augustus in 1764. Catherine and fellow predators took their first helpings of his country in 1772.

Fifteen years later the Framers’ first stab at a constitution, the Virginia Plan, envisioned a chief executive chosen by the national legislature. On second thought, however, the Framers realized a president picked by Congress would be no less vulnerable to foreign influence than a Poniatowski picked by the Polish sejm.

“The great rival powers of Europe who have American possessions,” said James Madison, will want to see “at the head of our government a man attached to their respective politics and interests.” This was no idle worry.

Great imperial powers surrounded America. Former masters the Brits owned Canada; Spain controlled the Mississippi River and the Gulf coast. And who could say when France, still ensconced in the Caribbean, might chance a return to the North American mainland?

“The election of a President of America,” Thomas Jefferson warned Madison in a kibitzing communique he posted from Paris, “will be much more interesting to certain nations of Europe than ever the election of a king of Poland was.”

The solution, not settled until the Constitutional Convention’s final weeks, was to have each state’s voters choose electors. Those electors—the phrase “electoral college” came into vogue in the 19th century—would pick the president and vice president. This scheme’s main virtue, Alexander Hamilton explained in the Federalist Papers, was that the electors would be a serial pop-up group. “The appointment of the President” does not “depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes,” Hamilton wrote, but on persons picked “for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment.” As an extra safeguard, senators, representatives, and other federal officeholders could not be electors, lest they support an incumbent pursuing re-election. Since each state’s electors would meet in that state’s capital—initially 13 locations, more as the country grew—foreign influencers would be hard pressed to lobby electors even at the last minute.

The arrangement evolved by evolution and amendment. At first some states chose electors by popular vote, others via their legislatures. In time, a popular vote with the statewide winner taking all became the norm; Maine and Nebraska choose some electors in separate electoral districts.

In the first four presidential elections, each elector voted for two men, the one who got the most votes becoming president, the runner-up becoming veep. The 12th Amendment, ratified early in 1804, required electors to declare their first choices, institutionalizing not only the presidential ticket, with a POTUS candidate and a running mate, but the system of political parties that picked those tickets.

Although Hamilton’s comments in the Federalist Papers suggested otherwise, electors were always expected to vote as the states that chose them directed, though in recent years the elector who goes his own way has become more common. In 2016 five of Hillary Clinton’s electors and two of Donald Trump’s went rogue. Thirty-three states and the District of Columbia have laws against bolting.

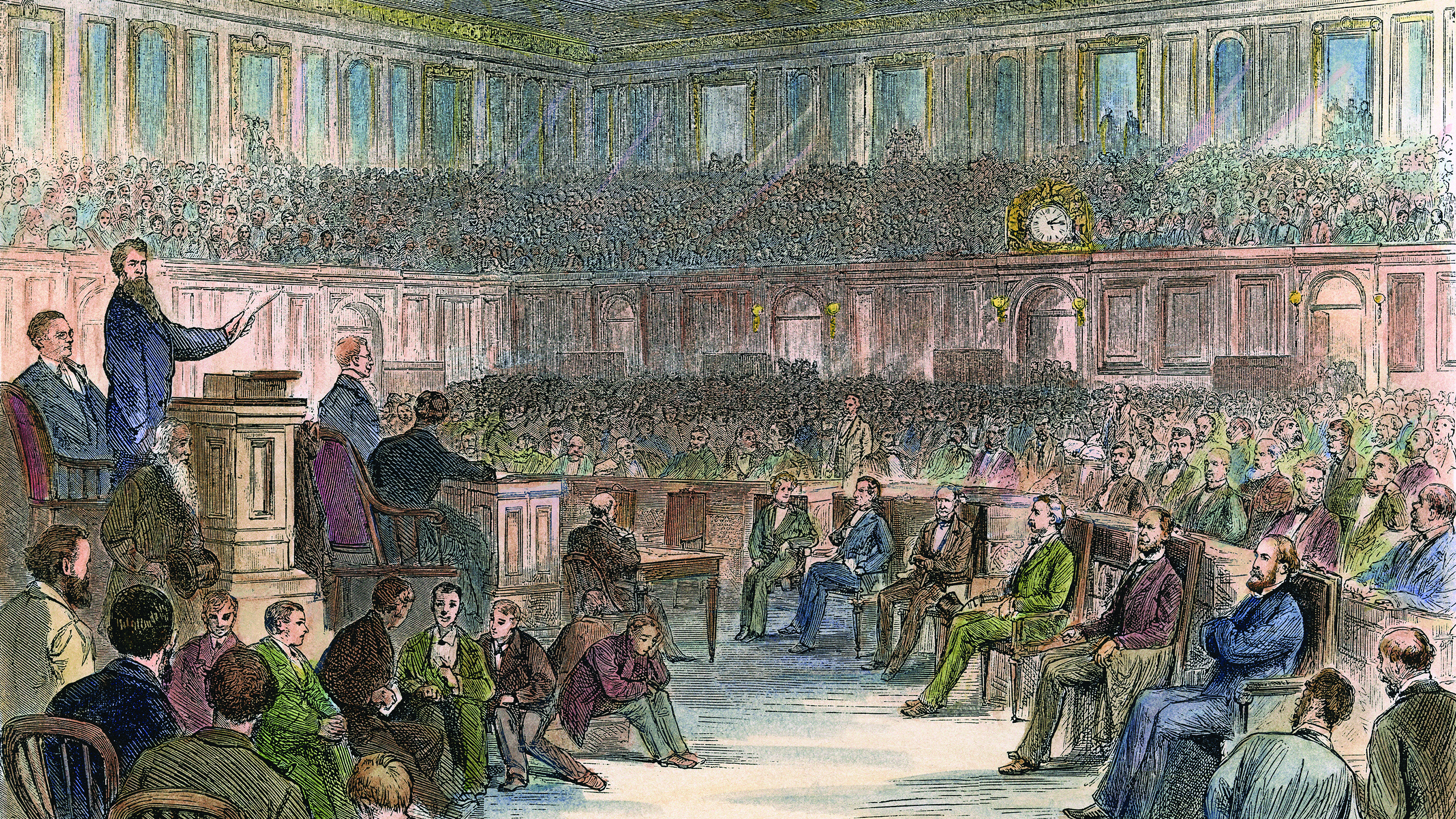

The Electoral College has delivered its share of crack-ups. In 1800 and 1824, the House of Representatives decided the election, because no candidate won a majority of electoral votes. In 1876 three states each sent two conflicting slates of returns, while a fourth state’s tally was challenged because one elector was a federally employed postmaster. An Electoral Commission of senators, representatives, and justices of the Supreme Court sorted out the mess. The biggest problem, which grows bigger as America thinks of itself as more democratic, has been disparity between the Electoral College count and the votes that John Q. Citizen actually casts. Several presidents who racked up big Electoral College margins won only pluralities of the popular vote—Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Woodrow Wilson in 1912, and Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996—thanks to third-party candidates’ vote-draining effect. And in 1888, 2000, and 2016 Electoral College winners Benjamin Harrison, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump trailed rivals Grover Cleveland, Al Gore, and Hillary Clinton in the popular tally.

Is the Electoral College still a shield against fraud? Foreign countries have been trying to influence American elections as far back as 1796, when France was threatening grave consequences unless a Francophile candidate, meaning Jefferson, won, and as recently as 2016, when Russia reached out to the Trump campaign with multiple tentacles. But foreigners could not tamper with the vote.

One unintended consequence of the Electoral College may be the blunting of homegrown vote-stealing in presidential contests. Every political machine tries to thumb the scale, but perhaps only in 1844 did that tip an election. Historian Daniel Walker Howe argues that Henry Clay lost New York’s electoral votes, and thus the race, not only because the abolitionist Liberty Party diverted anti-slavery Whigs from Clay—the view taught in textbooks—but also through Tammany Hall skullduggery on behalf of victor James Polk. Richard Nixon’s 1960 campaign, believing vote stealing had thrown that contest to JFK, demanded recounts in several states. When Illinois, one of the largest, examined its returns, officials found fraud, but not enough to have changed the result. A recount in Hawaii actually moved that state from Nixon’s to Kennedy’s column.

Targeting decisive races in a continent-sized republic is difficult enough for the purposes of ordinary campaigning. For vote stealing it is a more difficult undertaking yet.

In a tight race decided by a national popular vote, however, any vote stolen anywhere would be worthwhile. The temptation to run up one’s candidate’s tally would be almost irresistible—and none would resist. National recounts would inevitably follow, like nightmares after a bad dinner. Such a system could work only with a national voter ID card.

So we bumble along with a college whose members never meet en masse, and electors who should, but sometimes don’t, do what the voters who picked them want.

This Déjà Vu column appeared in the December 2020 issue of American History.