The Second Battle of Haw’s Shop gave the Union Army a needed reprieve during the unabated slaughter of June 3, 1864

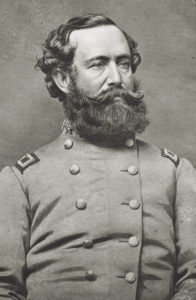

In early June 1864, Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson was a rising star in the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps—“a brilliant man intellectually, highly educated, and thoroughly companionable,” remembered former Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana, who nevertheless was quick to concede that Wilson was also “often imperious and outspoken, to the extent that he fully alienated as many people as he attracted.” The brash 26-year-old West Pointer from Illinois had to learn rapidly that spring. When he assumed command of the 3rd Cavalry Division, he had no experience leading large bodies of men in the field. On May 5, his division was at the fore of the Union army’s advance into the Wilderness, opening the Overland Campaign, and—to put it bluntly—he bungled the job, as his troopers were thrashed by a single brigade of Army of Northern Virginia cavalry. Wilson’s setback left his army with no cavalry screen as it advanced into the Wilderness’ snarled, second-growth forest and the unprepared Federals ran into Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Corps in Saunders Field—igniting the Battle of the Wilderness, a three-day conflagration that produced nearly 30,000 total casualties on both sides. Fortunately for the Federals, Wilson’s performance improved noticeably as the Overland Campaign progressed.

When Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant decided in late May to shift the Army of the Potomac’s base of operations away from Ox Ford on the North Anna River, Wilson’s division acted largely as an independent command. Guarding the army’s left flank, isolated and far from the rest of the Cavalry Corps, Wilson’s troopers fought protracted dismounted slugfests with Confederate cavalry at Hanover Courthouse on May 31 and Ashland on June 1, then spent June 2 on the march after learning the army’s main body had moved to Cold Harbor.

Wilson was to cross Totopotomoy Creek and make contact with the army’s right flank. He waited for reinforcements before proceeding—a hodgepodge regiment of remounted troopers commanded by Colonel Luigi Palma di Cesnola of the 4th New York Cavalry—but was unsuccessful. “It was nearly daylight June 3,” Wilson reported, “before my command, worn and jaded from its exhausting labors, bivouacked.”

“After so much hard fighting and marching the boys naturally expected a little rest,” complained a member of the 5th New York Cavalry. “Well, they got a little, and a very little rest it was. The time for an abundance of that luxury had not yet come.”

At 10 a.m., Wilson received orders to cross to the west side of the Totopotomoy, drive Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton’s cavalry away from Haw’s Shop, swing to the left again, and recross the creek near its source. Once he did so, he was to attack the left of the Confederate infantry line in conjunction with an assault by the infantrymen of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s 9th Corps. It took his troopers about two hours to break camp, saddle up, and prepare to move out.

The attack by the 9th Corps was to be part of an all-out assault by the Federals that day. Grant had wanted to attack on June 2, but 18th Corps commander Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith refused to obey the order. In addition, on June 1, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade had ordered the 2nd Corps, under Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, to march the 12 miles to Cold Harbor overnight to be in position to support another attack early on June 2. The 2nd Corps, which became lost during its grueling night march, did not arrive until about 6:30 a.m. Deciding to give Hancock’s exhausted troops a chance to rest, Meade postponed the attack until 5 p.m.; however, concerned that Hancock’s men wouldn’t be ready to attack, Grant suggested that Meade should instead wait until the next morning.

The opportunity was lost. Robert E. Lee took advantage of the Union delay and his army constructed an extensive and intricate set of earthworks to strengthen his position on the heavily wooded and rolling battlefield.

At 4:30 a.m. June 3, the Federal 2nd, 6th, and 18th Corps stepped off through the inky darkness and thick fog. Their assault bogged down in swamps, ravines, and dense woods, causing the corps to lose contact with each other. The alignment of the Confederate earthworks permitted the Southerners to enfilade Meade’s attackers as they approached.

The Army of the Potomac lost several thousand men killed and wounded in the opening moments of the assault, and the severe bloodletting would last the entire morning. Elements of the 2nd Corps briefly captured some of the Confederate earthworks, but the Southern artillery quickly turned those works into bloody traps. Because of the terrain, the men of the 18th Corps were funneled into two ravines, where they were mowed down by the Confederates.

Unable to advance, and in no position to retreat, the Union soldiers did the only thing they could—built earthworks of their own, sometimes using the bodies of dead soldiers as components of their hastily constructed breastworks. Grant finally called off additional attacks after riding the lines and seeing for himself that further assaults would also end with bloodshed. The battle’s management “would have shamed a cadet in his first year at West Point,” lamented a 6th Corps officer.

Grant concurred. “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made,” he wrote in his memoirs. “No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained.”

Troopers on both sides heard the frightful cataclysm raging at Cold Harbor. Recounted Sergeant George Neese of Chew’s Battery, a Confederate horse artillery unit: “The way the musketry roared and raged the fire must have been terrific at times, especially during the desperate charges of the enemy, when the Union patriots rush[ed] up against General Lee’s line like maddened sea waves dashing against an adamantine wall, and were slaughtered by the hundreds, yes, thousands.”

“The successive advances and recoils could be numbered by a listener, from the awful roar of musketry and artillery, and then the comparative cessation for short intervals,” declared Edward L. Wells, a private in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry’s Charleston Light Dragoons. Then, the sudden silence that fell over the battlefield signaled the end of the “fruitless butchery of twenty [Federals] to every one Confederate.”

Wilson knew nothing other than that a large battle was raging near Cold Harbor and that he was to coordinate his attack with Burnside’s planned move against the Confederate left as his column advanced toward Haw’s Shop. The tiny settlement was the location of a machine shop used for manufacturing farming and milling machinery, and renowned for the quality of the equipment it produced. After the Army of the Potomac occupied the area in 1862, John Haw III, the owner of the machine shop, sold his equipment to Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond. By 1864, the area had been largely abandoned and had fallen to ruins, leaving only Salem Presbyterian Church and a few houses standing.

That included the Haw homestead, a quaint two-story house known as Oak Grove. John Haw lived with his wife and their 24-year-old daughter at Oak Grove; his three sons were serving in the Confederate Army. Enon Methodist Church was located half a mile farther west. With stout wooden fences and dense woods lining both sides, the Atlee Station Road passed by Oak Grove. Five roads converged there, including two that led directly to Richmond via Atlee Station.

On May 28, the other two divisions of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps had tangled with Hampton’s horsemen at Haw’s Shop—a harsh, grinding, day-long dismounted fight. At the end of the day, the Federals held the battlefield, but Hampton’s troopers had prevented the Union cavalry from locating the Army of Northern Virginia’s position.

About noon on June 3, Wilson left Cesnola’s men to guard Burnside’s right flank and marched his command from its Old Church camp. They crossed Totopotomoy Creek and headed northwest toward Haw’s Shop, where they intended to turn south and attack the rear of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s Division in Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Corps. Wilson’s division arrived at Haw’s Shop about noon, and his men quickly occupied breastworks that had been erected during the battle six days earlier. He did not expect an encounter, but deployed pickets on the Atlee Station Road and other roads nearby.

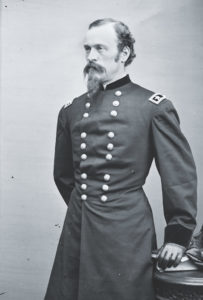

The 46-year-old Hampton, now commanding the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps after the May 12 death of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, was still learning the art of corps command. He had, after all, no formal military training and was relying on pure talent and on-the-job training. Joined by elements of Maj. Gen. W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee’s cavalry division and Captain James Thomson’s battery of horse artillery, the skilled Chew’s Battery, Wilson’s troopers marched from their camp not far from Atlee Station on the Virginia Central Railroad early that morning. “We made a circuitous march of about eighteen miles in the direction of the Pamunkey,” recounted Sergeant Neese.

As he had done on May 28, Hampton rode east toward Haw’s Shop, unaware he was heading straight for Wilson’s division. Leading the Confederate column were the 2nd and 5th North Carolina Cavalry, part of a brigade temporarily under the command of 3rd North Carolina Colonel John A. Baker following the death of the regular brigade commander, Brig. Gen. James B. Gordon, on May 12.

Upon reaching Haw’s Shop, the Tarheels ran into the 8th New York Cavalry, part of Colonel George H. Chapman’s 2nd Brigade. The North Carolina troopers dug in their spurs, drew their sabers, and charged the New Yorkers with “deafening yells”—catching the Empire Staters by surprise. The 2nd and 5th North Carolina led a quick rout, driving the 8th back toward the rest of the Federal brigade. Rooney Lee ordered the Southern horsemen to dismount and attack. Roberts and his men dismounted, formed a line of battle, and advanced against the Union breastworks, drawing fire from the Federal horse artillery as they proceed.

Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Barringer of the 1st North Carolina Cavalry had a clear view of Roberts’ attack. He watched as the 2nd and 5th North Carolina “charged at once the enemy’s line which was driven rapidly through a thick wood, back into a line of works, which was charged, and carried in a most impetuous style, driving the enemy back upon another line of entrenchments, with heavy support.” Chapman disputed Barringer’s assessment. “[T]he enemy made a spirited attack,” he wrote, “but were repulsed with severe loss, leaving a number of their killed and wounded upon the ground.”

“This spirited and dashing affair,” Barringer noted, “was executed under the eye of General Hampton, and elicited his special commendation.”

As the opening phase of the fighting played out, the four guns of Chew’s Battery unlimbered near Haw’s Shop and opened upon Wilson’s horse artillery. “We had a warm and spirited artillery duel with them of a couple hours’ duration,” noted Sergeant Neese.

Once he could form a coherent line, Chapman ordered a counterattack. “Moving forward under a heavy fire my men drove the rebels from [the first line of works] and they fell back to another line of breastworks,” he recounted. Among the 8th New York troopers involved in the attack, Lt. Col. William H. Benjamin was painfully wounded in the leg; Lieutenant Harmon P. Burroughs suffered a chest wound; one private was killed, one captured, and several wounded.

Realizing he faced at least a brigade of cavalry and that he was outnumbered, Roberts pulled back and established a dismounted line of battle in a dense stand of woods southwest of Haw’s Shop. The Tarheels constructed three lines of hastily constructed breastworks and waited for the Federals to attack.

During the pause, Wilson penned a quick update to Army of the Potomac headquarters. “We have developed a considerable force at or near Haw’s Shop, with artillery in position,” he wrote. “I am pushing forward now, the enemy having been repulsed in three or four sharp dashes at our skirmish line.” Ominously, Wilson also reported that he had heard no activity at all along Burnside’s front.

About 1 p.m., supported by horse artillery, the 1st Vermont Cavalry and the 5th and 8th New York Cavalry all dismounted and crashed into the woods toward the Confederate works, prompting Major William Wells of the 1st Vermont to observe that his regiment had been dismounted every day since they had crossed the Rapidan at the outset of the Battle of the Wilderness. The Vermonters took position with one battalion on the right of the road and the other two on the left when they were ordered to go to the left toward the enemy’s flank. Wilson proudly watched as his troopers advanced steadily in open order, “their rapid-fire carbines pouring out volley after volley, capturing prisoners and clearing up the country as they went along.” A Vermonter described the action as “Indian style,” the men fighting from behind trees as they advanced. “We…drove them killing and capturing quite a number of them,” noted a fellow trooper.

During this advance, Lt. Col. Addison W. Preston, the hard-fighting commander of the 1st Vermont, ordered Wells to place his battalion in line on the left, telling the major, “[D]on’t allow your men to fire, for our men [from other regiments] are in your front.”

Drawing heavy fire, the Vermonters dropped and began firing from the ground. While reconnoitering in front of his regiment’s line of battle, Preston was mortally wounded, shot in the back, the bullet passing near his heart. Trooper H.P. Danforth of Company D tried to retrieve Preston’s body. Spotting a group of Confederates behind a clump of trees—possibly soldiers who had shot Preston—he stood up to fire at them, only to receive a bullet to his shoulder that whirled him around like a top. “He was not so much hurt, but that he walked to the rear, and was sent to [a] hospital,” recalled Sergeant Horace K. Ide of the 1st Vermont. “From [the] hospital he went home on furlough and there died.”

As the Vermonters flanked Roberts’ left, Rooney Lee ordered the North Carolinians to withdraw, while the pursuing Yankees simultaneously pressed their right and front. “The cross fire of artillery and musketry just mowed down the rebels,” observed a Northerner. Roberts and his men pulled all the way back to Enon Church, abandoning Haw’s Shop to the Federals.

The 2nd and 5th North Carolina managed to halt the Union counterattack at Enon Church until relieved by the 3rd North Carolina Cavalry. The 3rd held on for about another hour, then withdrew in an orderly fashion, on Hampton’s orders, leaving only a few pickets in the road. Roberts’ command suffered about 20 casualties during the clash.

At 2:40 p.m., Wilson reported to Meade: “The enemy seems to have withdrawn on the road to Enon Church, but certainly toward the fortifications originally occupied by their infantry. I am now covering with the main body of my force the road to Hanovertown and the Totopotomoy,” he wrote, “and have sent part of a regiment to cross the creek near its head…with instructions to ascertain the position of the enemy’s infantry if possible.”

“I do not think it would be judicious to relinquish this position for a movement with my whole force in the direction toward Bethesda,” Wilson concluded. “I will threaten it.”

Having driven the Confederate cavalry away, Wilson and his division crossed the Totopotomoy, placed a section of horse artillery there, dismounted, and expected to join Burnside’s attack on Heth’s infantry. Unknown to Wilson, however, Burnside had called off his attack when he learned that Grant had canceled an offensive along the entire Army of the Potomac front after the failure of his attacks at Cold Harbor that morning. Burnside’s decision not to move against the Confederate flank left the unaware Wilson and his troopers to contend with the stubborn Confederate infantry on their own.

Chapman, with about 400 troopers of the 2nd New York Cavalry and the 3rd Indiana Cavalry, along with Captain Dunbar Ransom’s 3rd U.S. Artillery, Battery C, forded Totopotomoy Creek and struck the 22nd Virginia Battalion of Brig. Gen. Birkett D. Fry’s Infantry in Heth’s Division, which was in position along the brow of a ridge.

Weapons of Choice

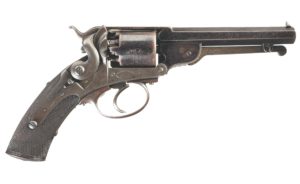

The muzzleloading, rifled 12-pounder Blakely was a favorite weapon of Confederate horse artillery units that supported their saber-wielding comrades. Invented in Britain by Theophilus

Alexander Blakely, the gun came in various sizes and calibers. The 3.5-inch model shown below was commonly used by horse artillery. Other weapons of choice for many Confederate troopers, shown below, were the Kerr revolver and the M-1840 sword, nicknamed the

“Old Wristbreaker.” Though cumbersome to wield in action, the M-1840’s size (a 35-inch-long blade) and weight were critical attributes in combat, when one slash might be enough to kill or incapacitate an opponent. Adopted by the U.S. Army before the war, it was standard issue for many Union troopers as well. Like the Blakely, the 5-shot, single-action Kerr revolver was imported from Britain. Just over 12 inches in length, with a 5-inch barrel, it was dependable and easy to care for and fire—a valuable attribute for mounted cavalrymen. –C.K.H.

The dismounted troopers attacked while supported by their horse artillery. The Southerners claimed that they “drove them back with ease,” but the Union horsemen disputed that, arguing that they had pulled out on their own.

“The rebels after firing a few shots broke and fled, leaving 10 or 15 prisoners in our hands,” Wilson reported. “Failing to establish communication with the infantry on my left, I withdrew to the [north] side of the Totopotomoy.” To Wilson’s surprise, he could hear no sound of any action from Burnside’s front. The weary Union horse soldiers held the Confederate trenches for about an hour before Wilson decided to break off and withdraw.

By then, it was nearly dark, and Lee, fearing his flank was in danger of being turned, withdrew his left wing from its position fronting the 9th Corps, effectively ending the Battle of Cold Harbor. The 3rd Cavalry Division returned to the junction of the roads leading to Haw’s Shop and Hanover Court House and bivouacked there in order to watch the roads in all directions.

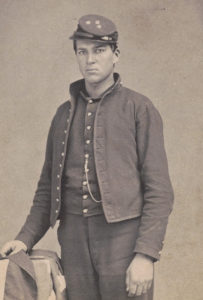

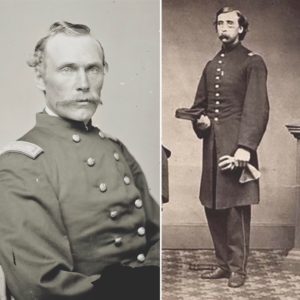

While the engagement still raged, Federal troopers attempted to rescue mortally wounded Lt. Col. Addison Preston. “Several times I tried to advance my lines to get [Preston’s] body but was driven back,” wrote Major William Wells of the 1st Vermont, “but the third time I got his body off, he was just alive, not conscious.” Some men threw water on Preston’s face to try to revive him, but it was too late. The men gently laid Preston’s body on a horse, holding him in place, and took him to the regimental surgeon, who confirmed he was gone. When the troopers attempted to get an ambulance to take Preston’s body to White House Landing, the surgeon in charge asserted bluntly that a live private was worth more than a dead colonel, noting that there were already more wounded than could be carried. Instead, the men made a rude coffin out of bureau drawers, gently laid Preston inside, placed it in a rickety old wagon, and proceeded to division headquarters, three miles away. En route, they passed Brig. Gen. George A. Custer, who, upon learning of Preston’s fate, looked at his corpse and remarked, “There lies the best fighting colonel in the Cavalry Corps.” Preston’s commission as colonel came through that day, too late for him to enjoy the deserved honor. Also killed in the fighting was Captain Oliver W. Cushman of the 1st Vermont. The intrepid, popular Cushman had survived a desperate wound to the face (still visible in the photo above) riding alongside Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth during Farnsworth’s ill-fated cavalry charge at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. Though left for dead on the field, Cushman would recover and later return to duty. “Ordinarily quiet, modest, unassuming—in battle the lion aroused within him, and he was the bravest of the brave,” declared one of Cushman’s friends. “[W]e lost one of our choicest and best.” Cushman’s body was placed into a hastily constructed coffin, similar to the one made for Preston, and both officers’ remains were transported to White House Landing to be sent home. Major Wells assumed command of the regiment. –E.J.W.‘There lies the best fighting colonel’

Wilson was justifiably pleased with the performance of his command in bringing about that result. “For its gallant conduct,” he declared proudly, “the division received the congratulations of General Meade. The operations were hazardous, and although entirely successful, cost us the lives of quite a number of brave officers and men.”

The Second Battle of Haw’s Shop may be remembered as just a small incident during the tragic fighting on June 3, but it nevertheless had strategic implications. Even though Burnside called off his attack on the left flank of the Army of Northern Virginia, once Wilson’s dismounted troopers drove away Hampton’s determined cavalry, the pressure they exerted on Heth’s position on the Confederate left helped persuade Robert E. Lee to pull back that exposed flank. That, in turn, prompted Grant to develop a plan to shift his base of operations across the James River and to move on the critical railroad junction town of Petersburg, 25 miles south of Richmond.

Eric J. Wittenberg, a regular America’s Civil War contributor, is the author of Six Days of Awful Fighting: Cavalry Operations on the Road to Cold Harbor (Fox Run Publishing, 2021), from which this article is adapted. His article on Wade Hampton and the First Battle of Haw’s Shop appeared in the May 2018 ACW.