How giant flying boats helped win the Pacific theater’s war of supply.

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox characterized World War II as “a war of supply.” This was especially true of the Pacific theater, where logistics were complicated by geography. The Pacific Ocean is the greatest body of water on the planet, encompassing some 64 million square miles of open sea speckled with islands—from huge Australia to tiny atolls that barely rise above the water. Allied success in the Pacific, therefore, would depend on supply and logistics in this vast theater.

In the early months of the Pacific War, the Philippines was under siege, Singapore had fallen and the Japanese were threatening Australia even as they swept through the Netherlands East Indies and gained footholds on New Guinea. General Douglas MacArthur, having escaped from Corregidor, was put in command of the Southwest Pacific Area, based in Brisbane, Australia. MacArthur had the dual responsibility of defending Australia and preparing an offensive against the Japanese. But once such an offensive was launched, it needed a steady stream of supplies, munitions and equipment to maintain momentum. Brisbane is more than 7,000 miles, or about 6,400 nautical miles, from the United States. In emergency situations, ships would take too long to provide urgently needed materiel. A delivery system that would take days, not weeks, was essential to Allied success.

The solution was the Naval Air Transportation Service (NATS), founded in December 1941, just a few days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Its formation recognized that only the airplane could conquer the vast distances involved in the Pacific theater, and deliver vital supplies, equipment and personnel in a timely manner.

Secretary of the Navy Knox and Naval Reserve Captain C.H. “Dutch” Schildhauer worked together to set up NATS. Initially there were three squadrons—VR-1, based at Naval Air Station Norfolk, Va., to serve in the Atlantic; VR-2, based at NAS Alameda, Calif., serving in the Pacific; and the landlocked VR-3 at NAS Olathe, Kan.—to in effect join the East and West coasts together.

VR-2 was formally commissioned on April 1, 1942, under Commander Samuel LaHache. Initially it comprised six officers, 66 enlisted men and a Douglas R4D (the Navy’s designation for the DC-3). The Pacific squadron quickly expanded; by 1945 it would boast 800 officers, 3,068 men and 54 aircraft.

The fledging service faced many challenges during its formative months, including a lack of pilots with transoceanic experience. But perhaps the greatest initial challenge was bridging the formidable 2,400-mile gap between California and Hawaii. For help, the Navy turned to Pan American Airways, which had been pioneering trails across the Pacific since the mid-1930s.

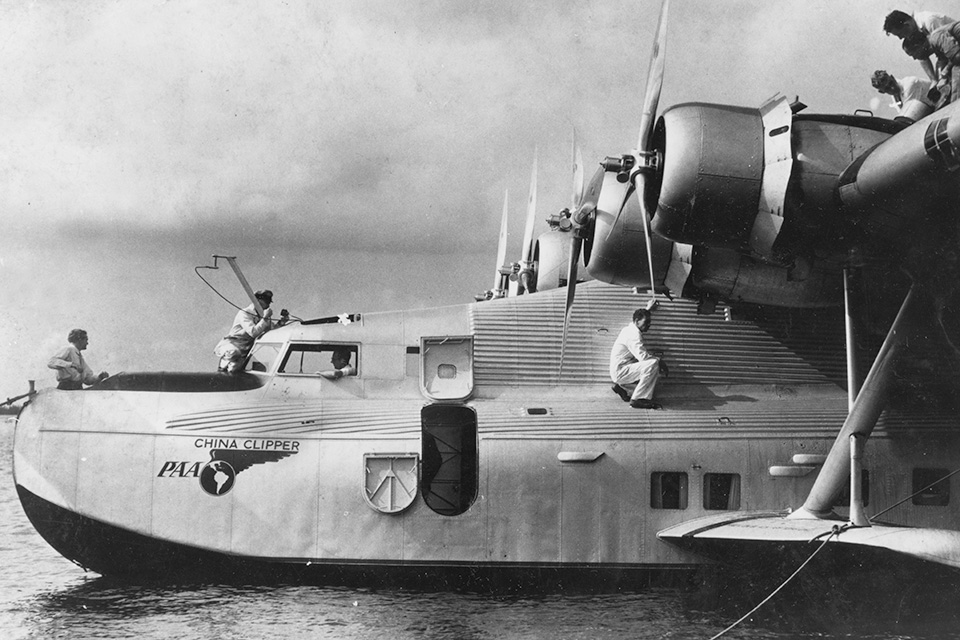

Juan Trippe, the airline’s hard-driving president, was an odd combination of ruthless businessman and visionary. Since the ocean was vast and airports few, Trippe had depended on flying boats to fulfill his Pacific dream. In 1935 the Martin M-130 China Clipper made the widely heralded first flight to the Orient. But Trippe was unsatisfied with the M-130s, accepting only three of them before he turned to Boeing, which produced the 314 and 314A for him. A dozen 314 Clippers would eventually be built.

When war came, Pan Am’s M-130s and 314s were among the only commercial aircraft capable of the long haul to Hawaii. Just as important, the airline’s employees could provide a pool of experienced pilots and workers for the hard-pressed new transport service. The Navy formed a partnership with Pan Am, making the airline an operator under military contract. According to the contract, which was formally inked in September 1942, the Navy would take over the airline’s three Martin 130s and the remaining Boeing 314s (three 314As had earlier ended up in British service). The airline’s personnel would also enter Navy service, more or less for the duration. Given the urgent need for personnel, a whole new generation of flight crews joined Pam Am’s NATS incarnation in 1943.

Clarence “Bud” Zahner was one of the young men who joined Pan American when it contracted with NATS. In a recent interview, Zahner recalled how green he and the other Pan Am recruits were at the time, even though they had the required 200 hours in the air needed to get a commercial pilot’s license.“We were very raw,” he said with a chuckle, “much more so than we thought. At the time, I hadn’t even had instrument instruction. I had months of ground training before I had an actual practical flight in the summer of 1943.”

Ed Dover served as a flight radio operator for Pan Am and NATS during the war. He noted that Pan Am crews were “enlisted into a special division of the Naval Reserve created for the express purpose of keeping NATS contract crews from being subject to the draft.”

When the war began, establishing a route across the Central and South Pacific was the first priority. The M-130s and 314s were used almost exclusively on the California-Hawaii leg, though in time Consolidated PB2Y-3s also flew that segment. After Hawaii, it was simply a matter of continuing to island-hop across the ocean.

Martin PBM-3R flying boats pioneered NATS flights southward in the fall of 1942. As the Japanese tide of conquest receded, more islands were added to the basic routes. A typical supply or passenger mission started by flying from California to Hawaii. After a brief stopover, it was on to Palmyra, some 1,100 miles to the south. Nanji, on Fiji, was the next stop, followed by Noumea, New Caledonia. Once the big flying boats touched down on Noumea, they were almost at the end of their journey. A final flight would take them to Brisbane, heart of offensive operations in the Southwest Pacific.

Crews didn’t necessarily fly the whole way from San Francisco to Brisbane, though if they did, it took about five or six days, said Dover. Yet Zahner’s flight log reveals that at one point he did nothing but shuttle back and forth from Hawaii to California for a whole month.

The flying boats were slow by today’s standards, but well suited to their new role. A typical mainstay, the PB2Y-5R Coronado, had a range of some 3,000 miles and a crew of six—with an orderly making it seven whenever passengers were transported. The Coronado could carry a payload of up to 15,000 pounds.

The NATS aircraft proved their worth from the very beginning. In 1942 PBM-3R Mariners flew vitally needed supplies to Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides. Upon arrival, the supplies were transshipped to the Solomons, some 540 miles distant, where Marines were engaged in a bloody fight on Guadalcanal.

NATS operations expanded as the war ground on. By June 1944, the service had more than 200 planes, transporting 22,500 priority passengers and 8.3 million pounds of cargo a month. In addition to flying in the Pacific, NATS aircraft traveled to Africa, Europe, South America and parts of Asia.

On some trips the cargo was classified as top priority. NATS transported such vital items as parts for submarines and naval vessels, aircraft engines, generators, anti-aircraft guns and blood plasma. In one celebrated incident, a submarine in the South Pacific desperately needed a part. The manufacturer fashioned one in 24 hours, and just four days later it was delivered to the sub via a NATS plane after a 10,000-mile journey.

Before the war the Boeing 314s and Martin M-130s were considered the epitome of luxury, adventure and romance by the American traveling public. The giant flying boats had logged a peripatetic record, ranging as far as New Zealand and Manila. Of course, in the 1930s and early ’40s airfares for long-distance trips were far above what the average person could afford, with round-trip fares hovering around $675 (roughly $7,000-$8,000 today).

For some reason NATS never let the M-130s and 314s venture beyond the California-Hawaii stretch, perhaps because the slow, unarmed flying boats were vulnerable to Japanese air attack. Nevertheless, the trip was anything but a milk run. Bad weather was a constant menace when flying to and from Hawaii, and there was no guarantee you’d reach your destination.

Bud Zahner recalled the many challenges crews faced on that run. China Clipper, the celebrated trailblazer to the Orient, was called the “sweet 16” by pilots, thanks to its registration number, NC 14716. Yet it was slow, barely making 125 mph. “The trip from San Francisco to Hawaii was about 18 hours, still air,” Zahner explained. “But in the winter there was a chance of encountering winds, even at say 5,000 feet. If you encountered really strong headwinds, say 100 mph, you might be actually standing still! And remember, a flying boat could only stay in the air about 24, maybe 26 hours, then would run out of fuel. That’s where the‘point of no return’ came in. Many times a flying boat would get so far, but would have to turn back.”

Zahner often flew as a supernumerary pilot, taking over the controls whenever the first or second officer needed a break on long flights, though he was fully qualified to take off and land the giant flying boats. Sometimes when a crosswind threatened he also served in another role: as “ballast.” If a Boeing 314 crew feared that a crosswind was going to unbalance the aircraft during takeoff, crew members would be sent into the wing as counterweights. Zahner explained: “The 314 had catwalks into the wings for maintenance. At the captain’s signal, I’d crawl into the space just behind the engine.” Ed Dover, who also performed this duty, recalled,“You’d be sitting there with a 1,600-hp engine roaring about a foot or so from your face!”

According to Zahner’s flight log for January 27, 1943, he was on China Clipper “searching.” That terse entry refers to a mission after the NATS M-130 Philippine Clipper crashed in Northern California on January 21 during stormy weather. The accident was later attributed to pilot error. The wreckage was eventually found in a mountainous area about seven miles from Ukiah, Calif. All 19 aboard perished, including Rear Adm. Robert H. English, commander of the U.S. Pacific submarine fleet, and three of his senior staff officers.

Late in the war, the Navy wanted flying boats that could carry bigger payloads than the PB2Y. Martin responded with the XPB2M-1R, which was significantly larger than the Boeing 314. It was in fact the biggest U.S. flying boat ever built—save for Howard Hughes’ H-4 Hercules, the infamous “Spruce Goose.”

The XPB2M-1R arrived at VR-2 in January 1944. Noted for its huge payloads—up to 35,000 pounds—the giant flying boat was quickly nicknamed “Old Lady.” The new transport made 78 flights on the California-Hawaii run before being retired in March 1945. It proved so successful that the Navy ordered 20 of a somewhat-redesigned version from Martin, the JRM-1 Mars. But the war ended before any of these new giants could see any real service.

After the war, improvements in landplanes and the rapid development of airports around the globe rendered the NATS aircraft obsolete. Though they were increasingly seen as dinosaurs, giant flying boats had proved to be a vitally important link during the global conflict, delivering people, weaponry, urgently needed spare parts and a host of other materiel to far-flung battle fronts. Virtually all of them had been scrapped or were in museums by the 1960s. The JRM-1 Mars is the sole exception: Coulson Flying Tankers in Canada is still operating two of them, Hawaii Mars and Philippine Mars, as fire bombers.

Eric Niderost teaches history at Chabot College in California, and is the author of 300 articles and three books. For further reading, he suggests: The Fighting Flying Boat: A History of the Martin PBM Mariner, by Richard A. Hoffman; and Operation Lifeline: History and Development of the NATS, by James Lee.

Originally published in the November 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.