Reuben Louis Goldberg—Rube Goldberg as the world knew him—did it all: He was an engineer, cartoonist, sculptor, author, inventor, and—for just a very brief time in 1919—a war correspondent.

Born in San Francisco on July 4, 1883, Goldberg as a child was obsessed with drawing and by age 11 was taking lessons from a professional artist. Goldberg’s father wanted him to be an engineer, but six months after earning a degree in engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, the young Goldberg landed a job as a sports cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1907 Goldberg made his way to New York City, and by 1915 he was earning more than $50,000 a year (thanks largely to newspaper syndication) and was generally considered to

be America’s most popular—and prolific—cartoonist.

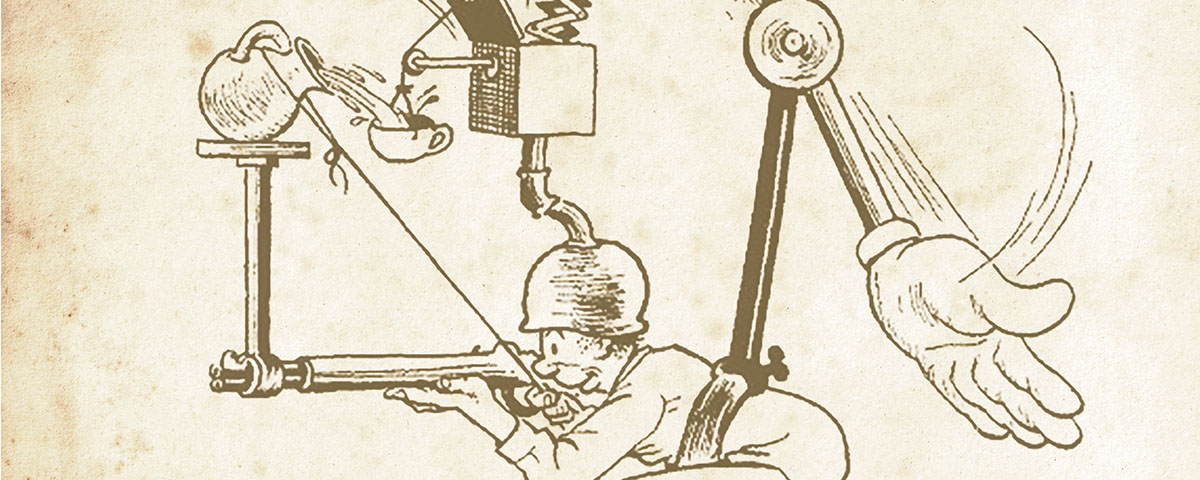

The cartoons that brought Goldberg lasting fame were built around fanciful devices that performed simple tasks in comical ways, typically in elaborate chain reactions (the “Self-Operating Napkin,” for example). These cartoons would also make him a household name (and, in time, make him the only person ever to be listed as an adjective in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

During World War II, troubled by the hatred directed at him because of the political nature of his cartoons, Goldberg insisted that his two sons change their surname.

Goldberg received many honors in his lifetime, including a Pulitzer Prize for his political cartooning in 1948. He died in 1970 in New York City, having produced an estimated 50,000 cartoons in his lifetime.

After the signing of the armistice that ended World War I, Goldberg traveled to Europe, where he launched a new comic strip, “Boobs Abroad in 1919,” for the Hearst newspapers. In March of that year he traveled to the heart of war-torn France, to what he called “the battlefields of freedom,” and after returning to Paris wrote about the experience for newspapers back in the United States.

This is the story he filed.

I have just taken a trip up through the St. Mihiel salient, over to Verdun and back along the Meuse into the Argonne Forest, and I am in a daze. While I seek for words to describe what I have seen I am filled with a great impulse to take the first boat back home and organize a gigantic expedition to convey the whole population of the United States to the battlefields of France.

We who have been fortunate enough to pass untouched through the terrible ravages of the war can only appreciate its true meaning by going direct to the scarred and devastated fields where thousands of our boys lie in graves that can only be called graves because they hold all that is left of those once brave lives.

I have read many books on the war and seen thousands of pictures of battlefields. When I came here I had a definite idea of what I was to see—the shell holes, the tangled barbed wire, the charred and broken trees, the ruined villages and the rest of it. It is exactly as I had expected it to be—that is, the physical aspect of it. In the distance you see what appears to be a cluster of stone houses where peasant folk live their simple lives in undisturbed happiness. Soon your automobile reaches the little village and you find yourself in the midst of partially standing, shell-torn walls and empty streets absolutely free from any human habitation. It is all just as you have seen it pictured in the movie news weeklies.

I can add little to the numerous camera and word pictures you have seen so often. But there is one thing that the camera cannot give you. It is the choking sensation you get when you see a small wooden cross alongside the road out there in the wilderness marking the spot where one of our boys gave all he had to give to keep the rest of us clean and free.

There was no identification tag attached to the wooden cross. The winds had already mocked the friendly hand that placed it there and torn it away. The cross itself was standing at a dangerous angle and would soon be destroyed by the elements, obliterating all records except the one that was burned into the hearts of those at home when they read their boy’s name in the dreaded casualty list.

We saw the lonely grave about ten miles beyond St. Mihiel. We found absolutely no signs of habitation until we reached a point ten miles beyond it. The loneliness and dampness and darkness of the place was terrible. Somehow my mind worked rapidly. I saw the boy at home cherishing his ambitions to go ahead in the world and make a name for himself and perhaps some day build his own little home. I saw him telephoning the one and only girl and asking her if she had a date for Saturday night. I saw him on the way home from the office reading the baseball news.

Then I saw him suddenly taken from the surroundings he had known since childhood and sent away to fight for reasons all of which were not quite clear in his mind. He smiled as he went away and was soon out there in the wilderness. Then he fell fighting. He died a glorious death in the name of patriotism.

And this was the grave of one of our noblest sons! The pathetic absurdity of it was enough to break a strong man’s heart. There he lay, one of our finest, thousands of miles away from his home, with no one to do him honor.

Perhaps President Wilson saw this crude grave. Perhaps he saw some of the others among the thousands that are scattered over the mutilated hillsides of Eastern France. Perhaps the paradoxical awfulness of these graves drove home to him the importance of the league of nations.

I know nothing about international politics. I know nothing about the claims of the Czecho-Slavs or the Poles or the Ukrainians. I know nothing about the ultimate working out of the self-determination of nations.

But I have seen the lonely grave of a fine American boy far away from home in a distant hill where those who love him cannot come to pray for his soul. And if they could come they would never find the spot where they might place a floral tribute to his memory.

And this boy had nothing to do with starting the war. He had nothing to do with the German military scoundrels who brought this great calamity into his life. He lay out there in the lonely marshes an innocent victim of the Kaiser’s loathsome ambitions.

Our one great absorbing thought should center on the prevention of all future wars. President Wilson’s plan for a league of nations may be a theory or it may be practical. I don’t know. But if it is one little step toward the prevention of conditions that will snatch an American boy away from home and place him in an unmarked grave in the desolate waste of a distant land, then I am for it heart and soul.

I have had an opportunity to see that President Wilson is the biggest figure in the Peace Conference. He will undoubtedly have his own way. And from what I can see his way will make us safe from all future wars. That is the only thing in the world that counts just now.

I have heard wise men say, “There must always be war. It has been so since the beginning of time. It is human nature.” If this be so, then I am sorry for our children and our children’s children. We have reason to be ashamed of ourselves.

But I don’t believe that human nature is depraved. Talk to soldiers who have been through it all and hear what they have to say about war.

No one who has seen a lonely American grave in France will ever call President Wilson a theorist. MHQ

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Lonely Grave

![]()