Michael Kelly went to war, as a journalist, on his own terms. In 1990, following stints as a reporter for the Cincinnati Post and the Baltimore Sun, he decided to do an end run around the Pentagon’s tight restrictions on the news media for Operation Desert Storm and cover the conflict as a freelancer. “I wanted to go to Baghdad and see the beginning of the war and write something about it,” he later told an interviewer. “I had no larger thought in mind.”

Kelly ended up staying for the duration of the Gulf War, and his dispatches from the front, like the one reprinted here, brought him a boatload of accolades, including a National Magazine Award and an Overseas Press Award. They also formed the basis of a book, Martyrs’ Day: Chronicles of a Small War (Random House, 1993), which won the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction in 1994. David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, once said that Kelly’s account of the Gulf War stood alongside George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, about the Spanish Civil War, and Ernie Pyle’s reporting during World War II. Kelly went on to join the staff of the New Yorker and to become the editor, successively, of the New Republic, National Journal, and the Atlantic Monthly.

Then came the second Gulf War. Kelly decided to drop the project he was working on (a book about the steel industry) and head back to Iraq, this time as an embedded correspondent with the 3rd Infantry Division. “He wanted to see the second act,” a colleague later recalled. “He needed to be a witness.” On April 4, 2003, as one of the division’s forward units was bearing down on Baghdad, the Humvee in which Kelly was riding with Staff Sergeant Wilbert Davis, a 15-year U.S. Army veteran, ran off a road near Saddam International Airport and into a canal, killing both men. Kelly, at age 46, was the first American reporter to die in the war.

Hendrik Hertzberg, who was Kelly’s editor at the New Republic during the first Gulf War, once recalled that nothing could have prepared him for the vivid dispatches that Kelly sent him, including the grisly depiction of post-battle carnage that follows. “He was just incandescent,” Hertzberg told Slate magazine on the day Kelly died. “War was the perfect subject for him. He was so full of emotion and yes, anger, too. And war was the subject that gave that its fullest scope.”

Along the Kuwait-Iraq border Captain Douglas Morrison, 31, of Westmoreland, New York, headquarters troop commander of 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, 1st Division, is the ideal face of the new American Army. He is handsome, tall and fit, and trim of line from his Kevlar helmet to his LPCs (leather personnel carriers, or combat boots). He is the voice of the new American Army too, a crisp, assured mix of casual toughness, techno-idolatrous jargon, and nonsensical euphemisms—the voice of delivery systems and collateral damage and kicking ass. It is Tom Clancy’s voice, and the voice of the military briefers in Riyadh and Washington. Because the Pentagon has been very, very good in controlling the flow of information disseminated in Operation Desert Shield/Storm, it is also the dominant voice of a war that will serve, in the military equivalent of stare decisis, as the precedent for the next war.

In the 100-hour rout, Captain Morrison’s advance reconnaissance squadron of troops, tanks, and armored personnel carriers destroyed 70 Iraqi tanks and more than a hundred armored vehicles. His soldiers killed many Iraqi soldiers and took many more prisoner. In its last combat action, the company joined three other American and British units to cut in four places the road from Kuwait City to the Iraqi border town of Safwan. This action, following heavy bombing by U.S. warplanes on the road, finished the job of trapping thousands of Saddam Hussein’s retreating troops, along with large quantities of tanks, trucks, howitzers, and armored personnel carriers. Standing in the mud next to his Humvee, Morrison talked about the battle.

“Our initial mission was to conduct a flank screen,” he said, as he pointed to his company’s February 26 position on a map overlaid with a plastic sheet marked with the felt-tip patterns of moving forces. “We moved with two ground troops [companies] in front, with tanks and Bradleys. We also had two air troops, with six OH-58 scouts and four Cobra attack helicopters. It is the air troops’ mission to pick up and ID enemy locations, and target handoff to the ground troops, who then try to gain and maintain contact with the enemy and develop a situation.”

The situation that developed was notably one-sided. “We moved into the cut at 1630 hours on Wednesday [February 27, the day before the cease-fire],” Morrison said. “From 1630 to 0630, we took prisoners….They didn’t expect to see us. They didn’t have much chance to react. There was some return fire, not much….We destroyed at least ten T-55s and T-62s….On our side, we took zero casualties.”

There hadn’t been much serious ground fighting on the two roads to Iraq because, as Morrison put it, “the Air Force had previously attrited the enemy and softened target area resistance considerably,” or, as he also put it, “the Air Force just blew the shit out of both roads.” In particular, the coastal road, running north from the Kuwaiti city of Jahra to the Iraqi border city of Umm Quasr, was “nothing but shit strewn everywhere, five to seven miles of just solid bombed-out vehicles.” The U.S. Air Force, he said, “had been given the word to work over that entire area, to find anything that was moving and take it out.”

The next day I drove up the road that Morrison had described. It was just as he had said it would be, but also different: the language of war made concrete. In a desperate retreat that amounted to armed flight, most of the Iraqi troops took the main four-lane highway to Basra, and were stopped and destroyed. Most were done in on the approach to Al-Mutlaa ridge, a road that crosses the highway twenty miles or so northwest of Kuwait City. There, Marines of the Second Armored Division, Tiger Brigade, attacked from the high ground and cut to shreds vehicles and soldiers trapped in a two-mile nightmare traffic jam. That scene of horror was cleaned up a bit in the first week after the war, most of the thousands of bombed and burned vehicles pushed to one side, all of the corpses buried. But this skinny two-lane blacktop, which runs through desert sand and scrub from one secondary city to another, was somehow forgotten.

Ten days after what George Bush termed a cessation of hostilities, this road presented a perfectly clear picture of the nature of those hostilities. It was untouched except by scavengers. Bedouins had siphoned the gas tanks, and American soldiers were still touring through the carnage in search of souvenirs. A pack of lean and sharp-fanged wild dogs, white and yellow curs, swarmed and snarled around the corpse of one soldier. They had eaten most of his flesh. The ribs gleamed bare and white. Because, I suppose, the skin had gotten so tough and leathery from ten days in the sun, the dogs had eaten the legs from the inside out, and the epidermis lay in collapsed and hairy folds, like leg-shaped blankets, with feet attached. The beasts skirted the stomach, which lay to one side of the ribs, a black and yellow balloon. A few miles up the road, a small flock of great raptors wheeled over another body. The dogs had been there first, and little remained except the head. The birds were working on the more vulnerable parts of that. The dead man’s face was darkly yellow-green, except where his eyeballs had been; there, the sockets glistened red and wet.

For a fifty- or sixty-mile stretch from just north of Jahra to the Iraqi border, the road was littered with exploded and roasted vehicles, charred and blown-up bodies. It is important to say that the thirty-seven dead men I saw were all soldiers and that they had been trying to make their escape heavily laden with weapons and ammunition. The road was thick with the wreckage of tanks, armored personnel carriers, 155-mm howitzers, and supply trucks filled with shells, missiles, rocket-propelled grenades, and machine-gun rounds in crates and belts. I saw no bodies that had not belonged to men in uniform. It was not always easy to ascertain this because the force of the explosions and the heat of the fires had blown most of the clothing off the soldiers, and often too had cooked their remains into wizened, mummified charcoal-men. But even in the worst cases, there was enough evidence—a scrap of green uniform on a leg here, an intact combat boot on a remaining foot there, an AK-47 propped next to a black claw over yonder—to see that this had been indeed what Captain Morrison might call a legitimate target of opportunity.

The American warplanes had come in low, fast, and hard on the night of February 26 and the morning of the 27th, in the last hours before the cease-fire, and had surprised the Iraqis. They had saturated the road with cluster bombs, big white pods that open in the air and spray those below with hundreds of bomblets that spew at great velocity thousands of razor-edged little fragments of metal. The explosions had torn tanks and trucks apart—the jagged and already rusting pieces of one self-propelled howitzer were scattered over a fifty-yard area—and ripped up the men inside into pieces as well.

The heat of the blasts had inspired secondary explosions in the ammunition. The fires had been fierce enough in some cases to melt windshield glass into globs of silicone that dripped and hardened on the black metal skeletons of the dashboards. What the bomb bursts and the fires had started, machine-gun fire finished. The planes had strafed with skill. One truck had just two neat holes in its front windshield, right in front of the driver.

Most of the destruction had been visited on clusters of ten to fifteen vehicles. But those who had driven alone, or even off the road and into the desert, had been hunted down too. Of the several hundred wrecks I saw, not one had crashed in panic; all bore the marks of having been bombed or shot. The bodies bore the marks too.

Even in a mass attack, there is individuality. Quite a few of the dead had never made it out of their machines. Those were the worst, because they were both exploded and incinerated. One man had tried to escape to Iraq in a Kawasaki front-end loader. His remaining half-body lay hanging upside down and out of his exposed seat, the left side and bottom blown away to tatters, with the charred leg fully fifteen feet away. Nine men in a slat-sided supply truck were killed and flash-burned so swiftly that they remained, naked, skinned, and black wrecks, in the vulnerable positions of the moment of first impact. One body lay face down with his rear high in the air, as if he had been trying to burrow through the truckbed. His legs ended in fluttery charcoaled remnants at mid-thigh. He had a young, pretty face, slightly cherubic, with a pointed little chin; you could still see that even though it was mummified. Another man had been butterflied by the bomb; the cavity of his body was cut wide open and his intestines and such were still coiled in their proper places, but cooked to ebony.

As I stood looking at him, a couple of U.S. Army intelligence specialists came up beside me. It was their duty to pick and wade through the awfulness in search of documents of value. Major Bob Nugent and Chief Warrant Officer Jim Smith were trying to approach the job with dispassionate professionalism. “Say, this is interesting right here,” said one. “Look how this guy ended up against the cab.” Sure enough, a soldier had been flung by the explosion into the foot-wide crevice between the back of the truck and the driver’s compartment. He wasn’t very big. The heat had shrunk all the bodies into twisted, skin-stretched things. It was pretty clear some of the bodies hadn’t been very big in life either. “Some of these guys weren’t but 13, 14 years old,” said Smith, in a voice fittingly small.

We walked around to look in the shattered cab. There were two carbonized husks of men in there. The one in the passenger seat had had the bottom of his face ripped off, which gave him the effect of grinning with only his upper teeth. We walked back to look at the scene on the truckbed. The more you looked at it, the more you could imagine you were seeing the soldiers at the moment they were fire-frozen in their twisted shapes, mangled and shapeless. Smith pulled out a pocket camera and got ready to take a picture. He looked through the viewfinder. “Oh, I’m not gonna do this,” he said, and put the camera away.

Small mementos of life were all around, part of the garbage stew of the road. Among the ammunition, grenades, ripped metal, and unexploded cluster bomblets lay the paltry possessions of the departed, at least some of which were stolen: a Donald Duck doll, a case of White Flake laundry soap, a can of Soft and Gentle hair spray, squashed tubes of toothpaste, dozens of well-used shaving brushes, a Russian-made slide rule to calculate artillery-fire distances, crayons, a tricycle, two crates of pecans, a souvenir calendar from London, with the House of Lords on one side and the Tower on the other; the dog tags of Abas Mshal Dman, a non-commissioned officer, who was Islamic and who had, in the days when he had blood, type O positive.

Some of the American and British soldiers wandering the graveyard joked a bit. “Crispy critters,” said one, looking at a group of the incinerated. “Just wasn’t them boys’ day, was it?” said another. But for the most part, the scene commanded among the visitors a certain sobriety. I walked along for a while with Nugent, who is 43 and a major in the Army’s special operations branch, and who served in Vietnam and has seen more of this sort of thing than he cares for. I liked him instantly, in part because he was searching hard to find an acceptance of what he was seeing. He said he felt very sad for the horrors around him, and had to remind himself that they were once men who had done terrible things. Perhaps, he said, considering the great casualties on the Iraqi side and the extremely few allied deaths, divine intervention had been at work—“some sort of good against evil thing.” He pointed out that there had not been much alternative; given the allied forces’ ability to strike in safety from the air, no commander could have risked the lives of his own men by pitching a more even-sided battle on the ground. In the end, I liked him best because he settled on not a rationalization or a defense, but on the awful heart of the thing, which is that this is just the way it is. “No one ever said war was pretty,” he said. “Chivalry died a long time ago.”

From The New Republic, April 1, 1991 © 1991 New Republic. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

[hr]

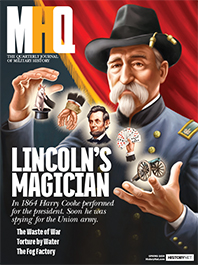

This article appears in the Spring 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Highway to Hell

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!