Elizabeth Caroline Butler

(1837–1911)

Born in Autaugaville, Ala., on October 7, 1837, Elizabeth Butler had, as a young girl, traveled west with her parents, extended family, and neighbors. At 18, she married Allan T. Daniel in Lauderdale County, Miss., and the following year gave birth to a daughter, Nancy. While pregnant with her second child—a son they would name Henry—Elizabeth traveled with her husband to the community of Eutaw in Limestone County, Texas, where he began working as a farmer and rancher. In early 1860, she would be blessed with twin boys, George and William.

Having to take care of four small children and managing the day-to-day struggles on the frontier was demanding enough, but Elizabeth was about to experience even more discord with the untimely death of her husband that April. The death of a spouse on the frontier was a common occurrence, of course, and Elizabeth did what many such widows did and remarried, this time to dry goods merchant and postal worker Isaac Ellison, nine years her senior.

To defend the Lone Star State’s interests during the war, Texans enlisted in droves at their county seats. Younger, unmarried men were usually the first to go, but Isaac was eventually among those called to duty. In his absence, Elizabeth strove to keep the dry goods store and post office running, while continuing to juggle being a full-time parent.

She had no respite in managing these commitments, and it didn’t help that money was difficult to come by. At this time, each Texas county issued its own paper currency. As the war progressed, Eutaw alternated within the jurisdiction of three counties: Limestone, Falls, and Robertson. County money soon became more worthless than regular Texas and Confederate script, leading to economic collapse.

As it did for communities and states across the country, four years of war decimated Texas’ male population. Having fought predominantly in Colonel James B. Likens’ Bloody 35th Texas Cavalry, Isaac would be one Lone Star boy fortunate enough to return home. —William Joseph Bozic

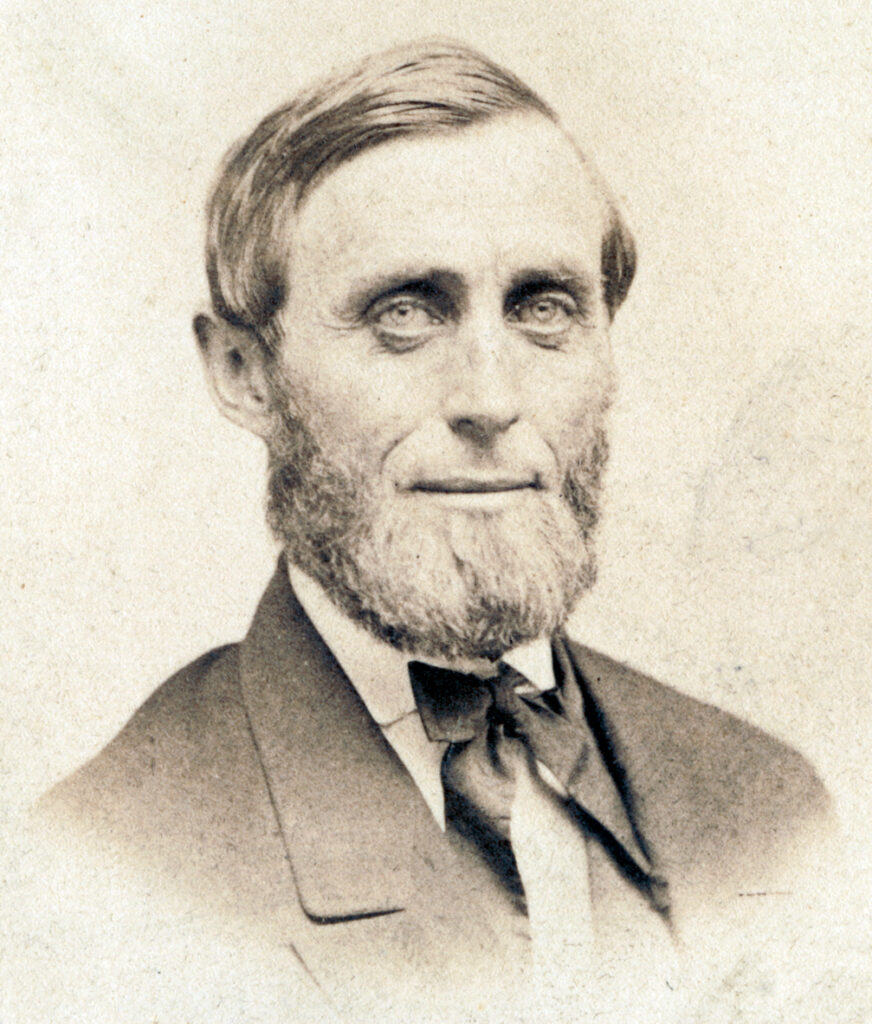

Charles Carleton Coffin

(1823–1896)

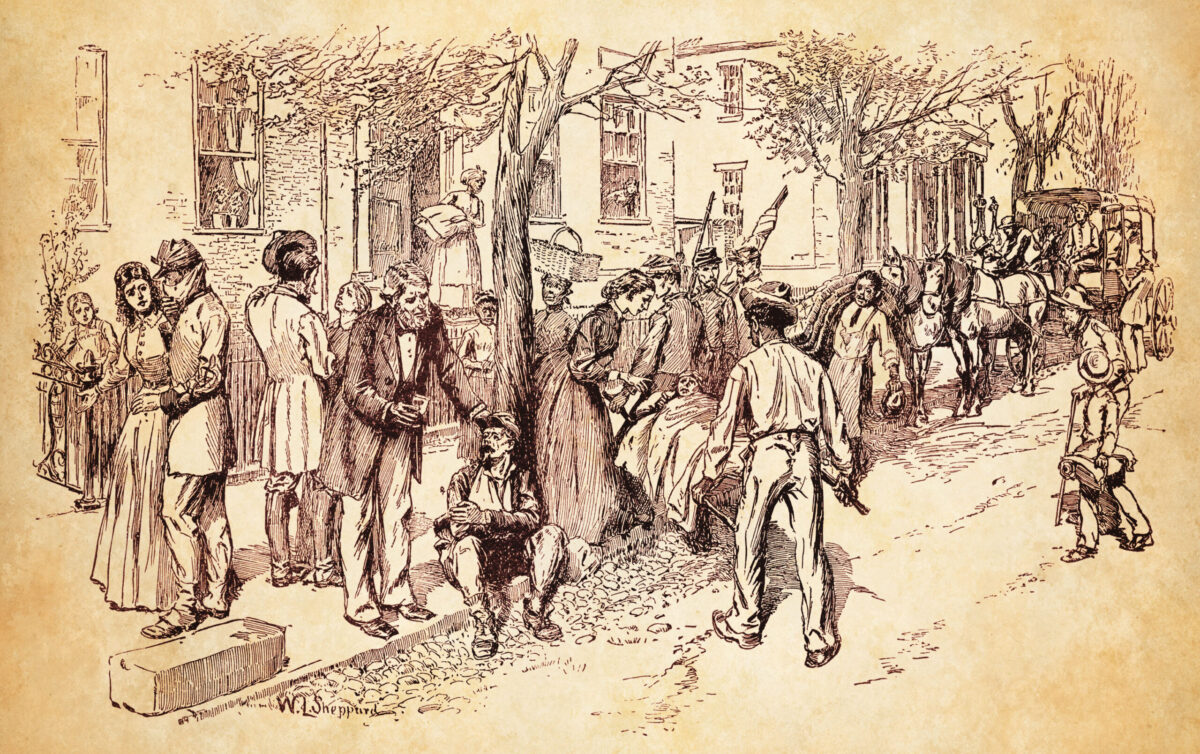

While writing for The Boston Journal during the Civil War, Charles Carleton Coffin was told by his editor to always “keep the Journal at the front.” In that, Coffin succeeded. Based in Washington, D.C., he first made a name for himself traveling into the field with what became the Army of the Potomac. His coverage of the Union army’s retreat at the First Battle of Bull Run, in fact, remains his most extensively quoted piece.

At Fredericksburg in December 1862, a Union soldier expressed amazement at seeing “Carleton” beneath a tree under fire, still writing away. The following spring and summer, Coffin followed the Union army to Gettysburg and ended up traveling 100 miles on horseback and 800 more by train to get accounts to the Journal’s readers.

During the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, Coffin had his nephew hurry his account to the presses in Washington. Ride as fast as you can, he urged; just don’t kill the horse. “If he is behind, his occupation is gone,” Coffin told his fellow war reporters (“specials,” as they were called). The “account must be the first, or among the first, or it is nothing.” If a reporter were to miss the mail or the train, he observed, “he might as well put his pencil in his pocket and go home.”

Coffin was one of more than 300 Northern correspondents to cover the war, earning about $25 a week. He shared with his colleagues a common set of vexations, such as the horse-stealing that frequently bedeviled field correspondents. On several occasions, Coffin’s servant greeted him in the morning, “Breakfast is ready, Mr. Coffin. Your horse is gone again.”

It is no surprise that Coffin’s name has a prominent place among Northern reporters inscribed on the War Correspondents Memorial Arch at Maryland’s Gathland State Park near Burkittsville. —Stephen Davis

Peter Bauduy Garesché

(1822–1868)

The authors of the 2007 book Never for Want of Powder make a compelling case that the Augusta (Ga.) Powder Works and its creator, Colonel George W. Rains, were instrumental to the Confederate Army’s survival as the war endured. Rains, however, had a counterpart in the Confederate Navy who shouldn’t be overlooked: Peter Bauduy Garesché.

Garesché’s father and uncle were French emigres who owned and operated a gunpowder mill in Wilmington, Del. The family were business partners of and relatives by marriage to the DuPonts of Wilmington’s famed DuPont Powder Mill family. Peter worked with his father in the mills as a youngster but eventually embarked on a career as a lawyer in St. Louis.

The Civil War divided the Garesché family. Peter’s cousin and close friend Julius Garesché, a fellow classmate at Georgetown University and a West Point graduate, remained loyal to the Union. Although Peter was a Southern sympathizer, he was not a secessionist, according to family sources. But when ordered to take a loyalty oath, he went south.

It helped also that he had strong Confederate contacts—General Joseph E. Johnston was his brother-in-law—and when the Confederate Navy was looking for someone to run its newly created powder works in Columbia, S.C., Garesché was chosen. It was a prescient decision.

Garesché was applauded for conducting the Columbia Naval Powder Works with “singular skill and commensurate results,” and for supplying the Southern Navy with gunpowder “of excellent quality.” Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who had known Peter while both were in St. Louis, purportedly told a friend: “I would, if I caught him, keep him close and not exchange him for 10,000 men. The powder he manufactures for the South is so superior to ours.”

After the war, Garesché resumed his law practice in St. Louis. He died in 1868. —Bruce Allardice

Mother Mary Hyacinth

(1816–1897)

In 1855, 39-year-old Madeline LeConniat, better known as Mother Mary Hyacinth, traveled to central Louisiana from her native France to open a convent and school along with nine other Daughters of the Cross. Louisiana would prove a harsh climate for her, often leaving her under the weather. The mosquitoes, she wrote, “[besiege] me continually because my blood which still smells European attracts them.” A lack of conversational English also hindered her local relations.

The Civil War increased already hard times with inflated pricing. Food and other supplies were in short supply, causing tense conditions for the nuns, students, and refugees alike. Troops from both sides constantly passed through the area, putting demands on their meager supplies.

The worst came during the Battle of Mansura on May 16, 1864, a contest featuring an artillery duel in which stray shots damaged the convent’s structures. In addition, soldiers looted the rations of the nuns and their wards. Relentlessly, Mother Hyacinth secured donations from the area’s residents to keep matters operating smoothly. She fervently kept the school running and still offered shelter to displaced individuals and families.

After the war, Mother Hyacinth continued to serve the convent and the neighborhood until 1867 when the motherhood discontinued its support of the Louisiana mission. Two years later, Mother Hyacinth was reelected mother superior and called back to Louisiana. She continued her community work without the support of the French motherhouse.

In 1882, at age 65, Mother Hyacinth returned to France to run the American novitiate until her death in 1897 at age 81. The Daughters of the Cross continued to operate schools throughout Louisiana into the next century, capitalizing on the sterling examples set by Mother Mary Hyacinth. —Edward Windsor

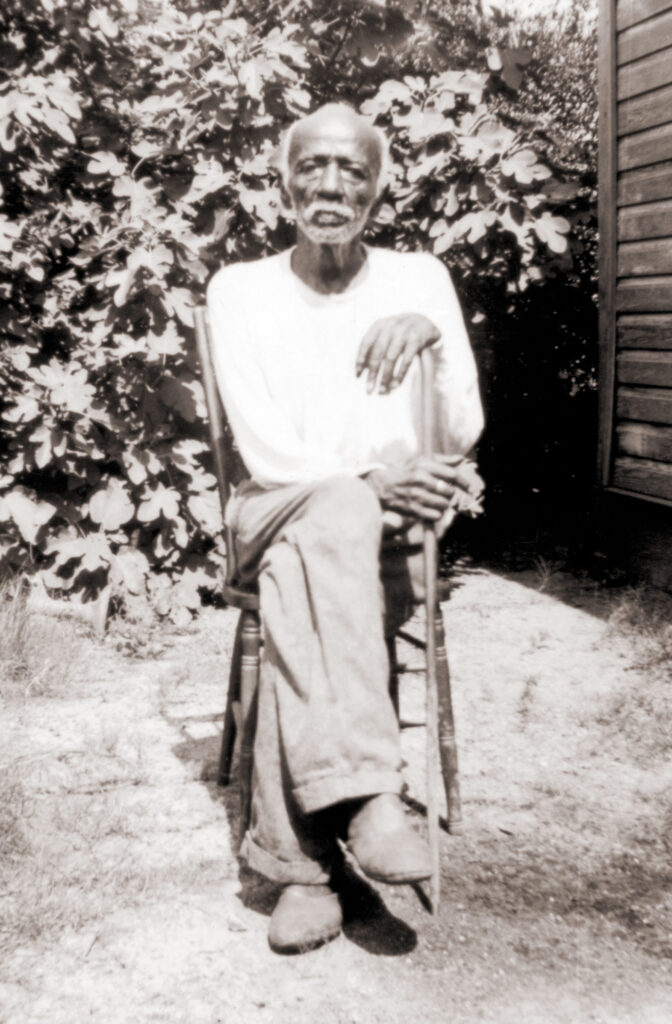

Martin Jackson

(Unknown)

As the Battle of Pleasant Hill, La., raged on April 9, 1864, Colonel Augustus Buchel of the 1st Texas Cavalry dismounted his troops and ordered them to attack the Federal infantry. Remaining on horseback, however, Buchel was an easy target and soon fell mortally wounded with seven injuries.

Two days later, Buchel died in the arms of a 17-year-old slave named Martin Jackson, a self-described “black Texan,” who lamented: “I had pitched up a kind of first-aid station. I remember standing there and thinking the South didn’t have a chance. All of a sudden I heard someone call. It was a soldier, who was half carrying Col. Buchel in. I [couldn’t] do nothing for the Colonel. He was too far gone. I just held him comfortable and that was the position he was in when he stopped breathing. He was a friend of mine.”

Martin and his father had followed their owner, Alva Fitzpatrick, to war to serve as cooks. Martin was also a stretcher-bearer, which he referred to as “an official lugger-in of men that got wounded.” Although Martin conceded, “I knew the Yanks were going to win from the beginning. I wanted them to win and lick us Southerners,” he also “hoped they was going to do it without wiping out my company.”

He remained fiercely loyal to the men of the 1st Texas throughout the war, continuing to cook for the men and tend the wounded. After the war, he was freed, became a cowboy, married, and eventually had 15 children. He even served as a cook in World War I, proudly claiming he never donned a uniform in either conflict. Martin’s one regret during the war—he started the deadly 75-year habit of smoking tobacco. —Fran Cohen

Cyrus Hall McCormick

(1809–1884)

Cyrus Hall McCormick, one of the United States’ great early industrialists, founded the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago in 1847. Although he was merely one of several entrepreneurs to invent a mechanical reaper, his company’s Chicago home, as well as his family’s business acumen, quickly made his version the nation’s most successful and widely used harvester, critically helping open the Midwest and Great Plains to family farmers in the decade leading up to the Civil War.

Born February 15, 1809, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, McCormick was the eldest of eight children raised by Robert McCormick Jr. and Mary Ann Hall. Robert McCormick had attempted to design and build a mechanical reaper of his own during Cyrus’ youth, but it proved not to be a sturdy, reliable model. Building upon his father’s failures, as well as an unpatented successful version by Scottish inventor Patrick Bell, Cyrus succeeded in constructing a reliable reaper in 1831. He continued working on improving this model and finally received his first patent in 1834.

Two years after Cyrus established the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company with one of his brothers, Leander, another brother—William—joined them in Chicago. William’s business insight and Cyrus’ skilled salesmanship helped the company flourish.

Cyrus, however, suffered a stroke in 1880 and spent the last four years of his life as an invalid before passing away in Chicago on May 13, 1884. In 1902, the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company was absorbed into the International Harvester Company. —Terry Beckenbaugh

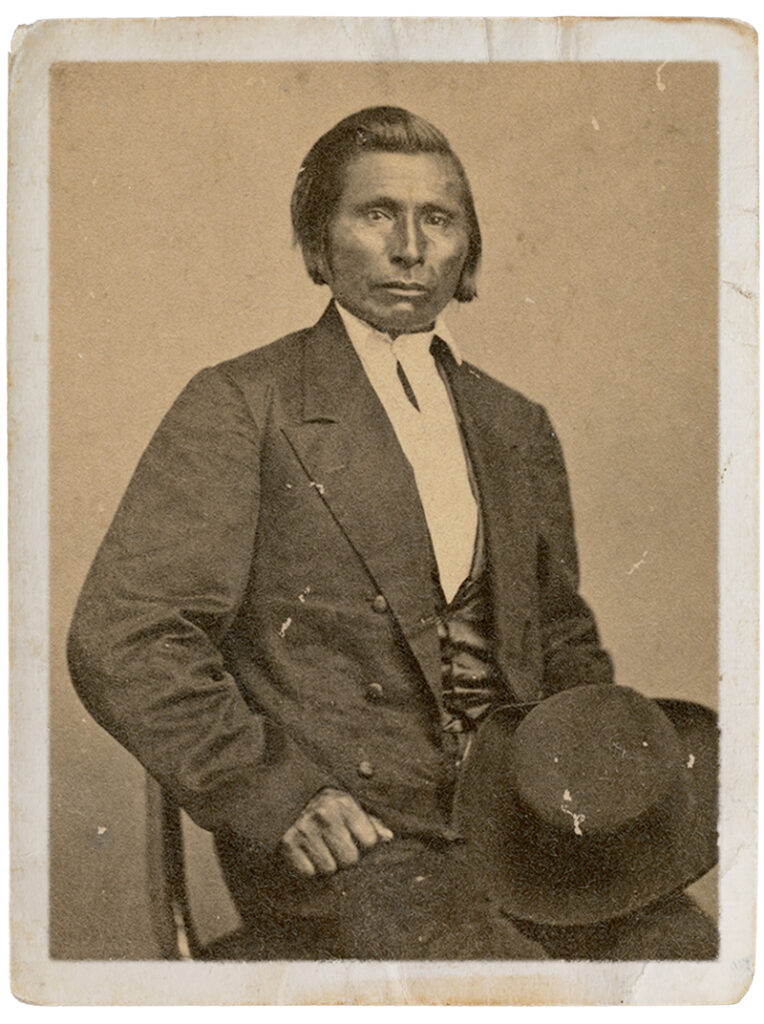

John Other Day

(1819-1869)

“When I gave up the war path and commenced working the earth for a living, I discarded all my former habits,” John Other Day once wrote. “It was very hard for me to learn the white man’s ways, but I was determined to get my living by cultivating the land and raising stock.”

Born Ampatutokacha (i.e., Good Sounding Voice) in 1819, Other Day had been a fierce warrior in his youth, but his conversion to Christianity led him to join an association of “farmer Indians” in 1856. The following year, Other Day assisted in the rescue of a young female captive, and in 1859 he was nominated to a treaty delegation sent to Washington, D.C. While on that trip, he met an English woman working at his hotel whom he later wed.

On August 18, 1862, Dakota Indians, upset with living conditions on their federal reservation in Minnesota, killed several settlers and traders during an armed attack on the Lower Sioux Agency, igniting the 39-day Dakota War of 1862. Other Day hurriedly gathered up 62 settlers (men, women, and children alike) and secured them in an Agency building overnight, personally standing guard at the door. Early the next morning, he guided the group on an arduous, three-day trek across the Minnesota River and through a prairie to safety in St. Paul, where he was welcomed as a hero. Wanting to further assist his new community, Other Day volunteered as a civilian scout for the U.S. troops assembled to combat the hostile Indians, often fighting side by side with his newfound comrades.

The U.S. government awarded Other Day $2,500 for his heroism. He bought a farm in Henderson, Minn., but later sold it and moved to the Dakota Territory. He would die of tuberculosis on October 19, 1869, at the Fort Wadsworth hospital in what became the state of South Dakota 20 years later. —Richard H. Holloway

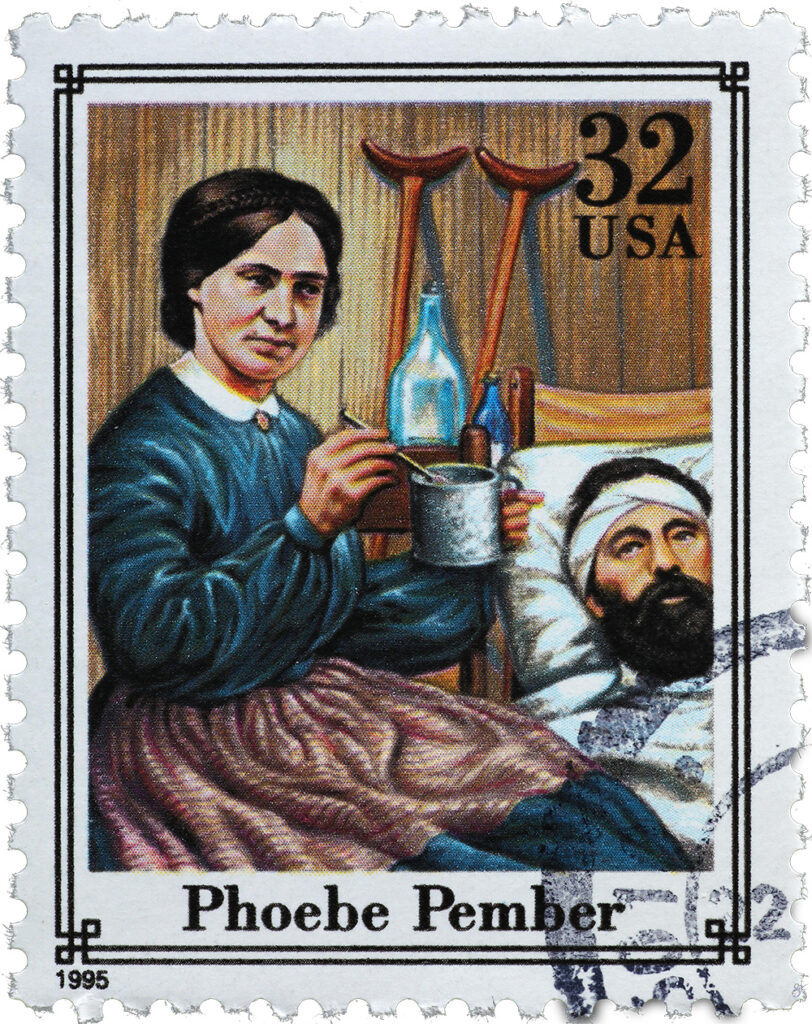

Phoebe Levy Pember

(1823–1913)

In April 1861, there was no reason to expect Phoebe Levy Pember would leave the mark on the Civil War that she did. Born into a prominent Jewish family in Charleston, S.C., she had spent the antebellum years in relative comfort, the well-off wife of a gentile, Thomas Noyes Pember, whom she married in 1856. As the nation formally began its split, however, her husband contracted tuberculosis, and she was widowed three months into the war. With no children and few career options, she relented to residing with her parents in Marietta, Ga. There she struggled, directionless and frequently at odds with her father.

That changed in November 1862 when Pember received an offer from the wife of Confederate Secretary of War George Randolph to move to Richmond to become “matron” of the capital city’s Chimborazo Hospital. Despite no previous nursing experience, Pember proved a providential choice for the position. According to the “Jewish Women’s Archive,” she “oversaw nursing operations as well as housekeeping and food and maintained a friendly but firm authority, loved for her feminine charms and her dedication to her patients.” That did not prevent her from pulling a gun on a hospital worker trying to pilfer whiskey from the hospital’s supplies.

Pember remained as Chimborazo’s first appointed female administrator until Richmond fell in April 1865. In 1879, she penned the book A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond, and in 1995 the U.S. Postal Service honored her with a stamp, featuring a painting of Pember feeding one of her patients chicken soup.

As historian James Robertson Jr. remembered: “Mrs. Pember was an aristocrat who developed a deep affection for the common soldiers and the class from which they came. She lived to be 89, but nothing in her life matched the three years of devoted service she gave to the human debris of war. Her only memorial were the looks of thankfulness that came from suffering soldiers who stretched out a hand for help—and found Phoebe Pember.” —Gregg Phillipson

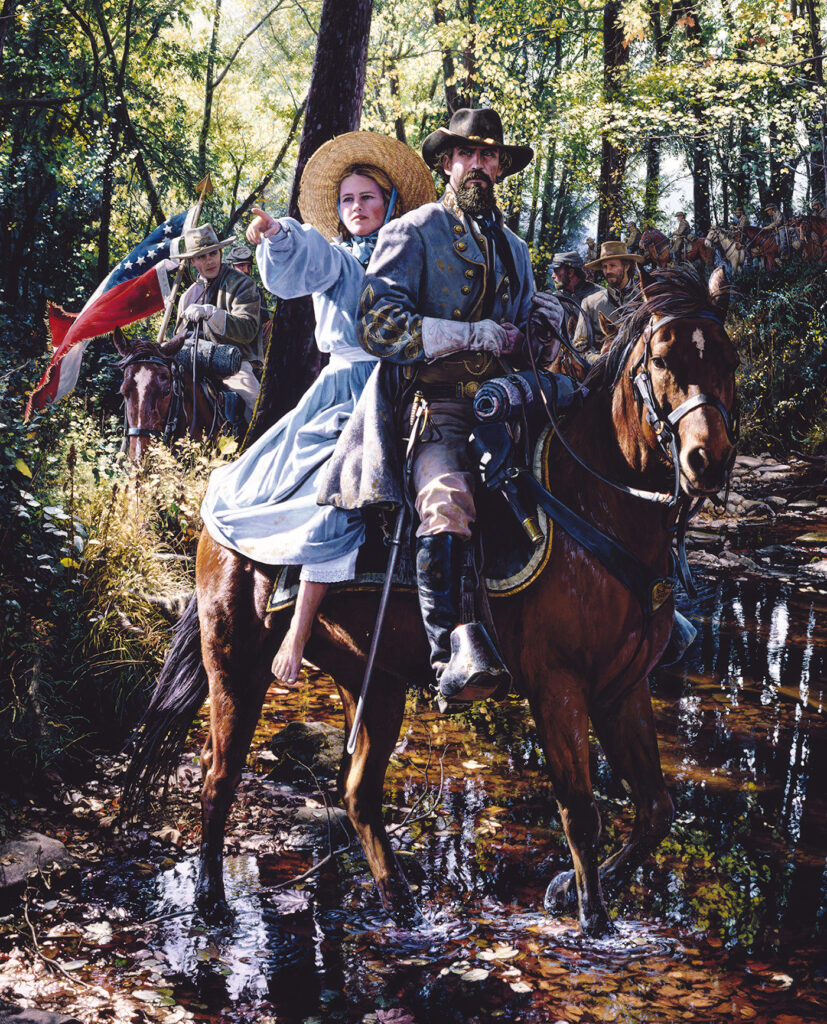

Emma Sansom Johnson

(1847–1900)

The Yankees were several miles ahead, with Nathan Bedford Forrest in earnest pursuit. A deep stream blocked the way, however. Where could he cross—and who would show the way?

It was late April 1863, and a 2,000-man mounted column under Colonel Abel Streight had ridden to northwest Alabama to wreck as many Confederate railroads as possible. On the morning of May 2, the Federals burned the bridge across Black Creek, north of Gadsden, Ala., believing it would stall Forrest long enough for them to get away.

The “Wizard of the Saddle” wasn’t stymied, though. A local girl, 16-year-old Emma Sansom, knew of a nearby ford. Forrest eagerly hoisted her onto his saddle as she pointed the way. After crossing the creek, the Confederates chased Streight and his troopers so determinedly that he surrendered his command the next day.

Forrest was quick to credit the lass with his success, writing her a note of thanks from his “Hed Quarters in Sadle.” Emma quickly became a local heroine. She married the next year, and after the war moved to Texas, where she died in 1900.

Seven years later, Gadsden residents unveiled a statue to her that, despite recent discussions of taking it down, remains standing—with Emma’s right arm held aloft, her index finger pointing of course to that famed Black Creek ford. —John Gordon

Fritz Tegener

(1813–unknown)

A Prussian immigrant, Fritz Tegener lived in the Texas Hill Country town of Comfort, a community started by recent German immigrants embroiled in the political unrest of the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe. Few German Texans owned slaves, and the people of Comfort were openly opposed to secession when the Civil War began, unwilling to participate in another such conflict.

Before the war, Tegener had been politically active in Comfort, serving as a jurist and county treasurer. That would continue during the Civil War. To protect the community from both Indian raids and the Confederacy, Tegener and other residents formed what was called the Union Loyal League.

After the Conscription Act of 1862 passed, Confederate soldiers began harassing the German Texans to join the Army, spurring more than 60 to organize a group that would travel south to Mexico to avoid conscription and appointing Tegener their leader. The ensemble departed in the summer of 1862, pursued by 94 Confederates as it traversed the rugged terrain of southwest Texas.

On August 10, 1862, the Confederates caught the Germans on the banks of the Nueces River and a battle ensued, known as the Massacre on the Nueces, in which 19 Unionists were killed and nine, too injured to escape, left behind and captured. Confederates executed their prisoners and left all 28 bodies unburied.

Though wounded, Tegener escaped and led the remaining Germans to Mexico, only to be ambushed by another Confederate group while crossing the Rio Grande. Eight more died.

Tegener spent the rest of the war in Mexico, but returned home afterward. Later, women of Comfort collected the sun-bleached bones from the battlefield and buried them under the only German language monument dedicated to the Union in the South named Treǔe der Union (Loyalty to the Union). Tegener risked his life to defend his political beliefs and find refuge for young German men of the Texas Hill Country. —Charles Grear

Alice Thompson

(1846–1869)

The ferocity of conflict often leads one to accomplish the unexpected. During the Battle of Thompson’s Station, Tenn., on March 5, 1863, teenager Alice Thompson—a progeny of the settlement’s namesake—made a split-second decision that helped change the course of an eventual Confederate victory.

Life had begun as usual that late-winter day, but Alice soon found herself caught in the midst of a desperate fray. Serving as Confederate physicians, Alice’s father as well as her beau remained near the front. She meanwhile fled her home, seeking protection for the rest of her family and finding refuge in the cellar of a neighbor, Confederate Lieutenant Thomas Banks. From the basement windows, she was able to catch glimpses of the conflict.

As the fighting intensified, Alice confronted a decisive moment. Having watched repeated Union advances and Confederate counterattacks, she became distressed watching a Southern flag-bearer fall to the ground. Forsaking her safety, Alice scrambled from the hiding place and made her way to the fallen soldier, grabbing the regimental colors—those of the 3rd Arkansas Cavalry—he had been carrying. Proudly holding the colors high, she drew the attention of Confederate troops, who were inspired by the recklessly courageous undertaking and rallied to push the Yankees back. Even with shells exploding around her, Alice reportedly never flinched as the Confederates advanced. Retreating Union troops were among those who admired her incredible bravery.

Finally, others concerned for Alice’s well-being pulled her back to the cellar. Her heroics did not end there, however. With Banks’ house serving as a hospital, she helped tend the wounded.

Alice Thompson died in 1869, only 23, but her gallantry at Thompson’s Station secured her place in Civil War history and memory. —Heidi Weber

Julia Wilbur

(1815–1895)

Julia Wilbur’s life easily could have slipped into historical anonymity. After years of a rather conventional rural life of teaching school and tending to the needs and wants of various members of a large and extended family, the spirited and socially aware Wilbur found herself caught up in the evangelical spirit burning through western New York. Residing in the environs of Rochester brought her into contact with prominent abolitionists and social reformers who, in the decades prior to the Civil War, advocated various forms of social and political change. Becoming a member of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society (RLASS) in 1852 probably rescued Wilbur from the life of an unassuming spinster and transformed her, at age 47, into an energetic social activist just as the nation was slipping into secession and war.

Determined to do more than darn socks and send food packages to the local boys in the Union Army, Wilbur traveled to Washington, D.C., as a representative of the RLASS. At first, she was armed with nothing more than a few general letters of introduction and a heart full of grit and compassion. After arriving on October 28, 1862, she was sent to Alexandria, Va., to do what she could to provide aid and comfort to the thousands of contrabands streaming into the Union-held city.

Nothing had prepared her for the sights, sounds, and, yes, smells she encountered. An entry in her diary described conditions she found upon her arrival: “Went to old School House. 150 C’s [contrabands] there. A large house for sick nearby. We went there, people in filth & rags—a dead child lay wrapped in piece of ticking—in another room, a dead child behind the door. Oh what sights! What Misery! No doctor—no medicines—only rations & Shelter.”

Along with her better-known friend—former slave and abolitionist Harriet Jacobs—Wilbur often encountered stubborn military bureaucracies, unfriendly local citizens, and various disorganized benevolent associations during her unrelenting fight against hunger, disease, and death. For the remainder of the war, Wilbur set about to change the dreadful conditions she found there.

Wilbur lived in Washington after the war and worked as a clerk in the Patent Office from 1869 to 1895, a harbinger of the thousands of women who would follow her into government employment. She remained active in social causes such as voting rights for women. She died on June 6, 1895, and is buried in the family plot in Avon, N.Y. —Gordon Berg

Contributors:

Dr. Bruce Allardice, author of the “Loose Lips” feature article in ACW’s Spring 2023 issue, teaches history at Illinois’ South Suburban College. He has co-authored several books and articles on the Civil War and on the history of baseball.

Dr. Terry Beckenbaugh is an associate professor of history in the Department of Joint Warfare at U.S. Air Force Command and Staff College, Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Ala. He is working on a book on the

1862 White River Campaign in Arkansas.

Gordon Berg, who writes from Gaithersburg, Md., is a longtime contributor to America’s Civil War, Civil War Times, and other HistoryNet publications.

William Joseph Bozic Jr., a retired Texas high school social studies teacher, works for the National Park Service in San Antonio. He is married with four children.

Fran Cohen, a freelance author specializing in history , writes from Little Rock, Ark.

Stephen Davis, who specializes in Southern Civil War history, writes from Cumming, Ga.

John Gordon is a freelance author based in Wetumpka, Ala.

Dr. Charles Grear, professor of history at Central Texas College, writes extensively on Texas and the Civil War. He is the author of Why Texans Fought in the Civil War.

Richard H. Holloway, a member of ACW’s editorial advisory board, is a historian who hails from Louisiana.

Gregg Phillipson is a former member of the Texas Holocaust Commission, well known for loaning his large collection of Jewish war memorabilia to museums across Texas. A resident of Austin, he also frequently delivers presentations about Jewish military history.

Dr. Heidi Weber is an associate professor in the SUNY–Orange Department of Global Studies, with specialties in U.S. history, the Civil War, and Reconstruction.

Edward Windsor, a retired historian and newspaperman, writes from Corinth, Miss.