“March 11, 1862…[P]art of the army had already gone, and there were hurried preparations and hasty farewells, and sorrowful faces turning away from those they loved the best, and were leaving, perhaps forever….Soon the heavy tramp of the marching columns died away in the distance. The rest of the night was spent in violent fits of weeping at the thought of being left….”

— First entry in Cornelia Peake McDonald’s diary

The threat of displacement, and worse, on the home front during war is an ancient one. Without a standing and accessible force for their protection, those who remain behind in the wake of a departed army find themselves at the mercy of the occupying troops, and of the inevitable crippling side effects of war in general.

Cornelia Peake McDonald was just one of the countless thousands who watched their loved ones and sole sources of support march off to war, and who then had to fend for themselves during the dark and often tragic times that followed. As did countless wives and mothers on both sides of the civil conflict that rent the nation, Cornelia fastidiously kept a diary detailing both everyday events and the news of the war.

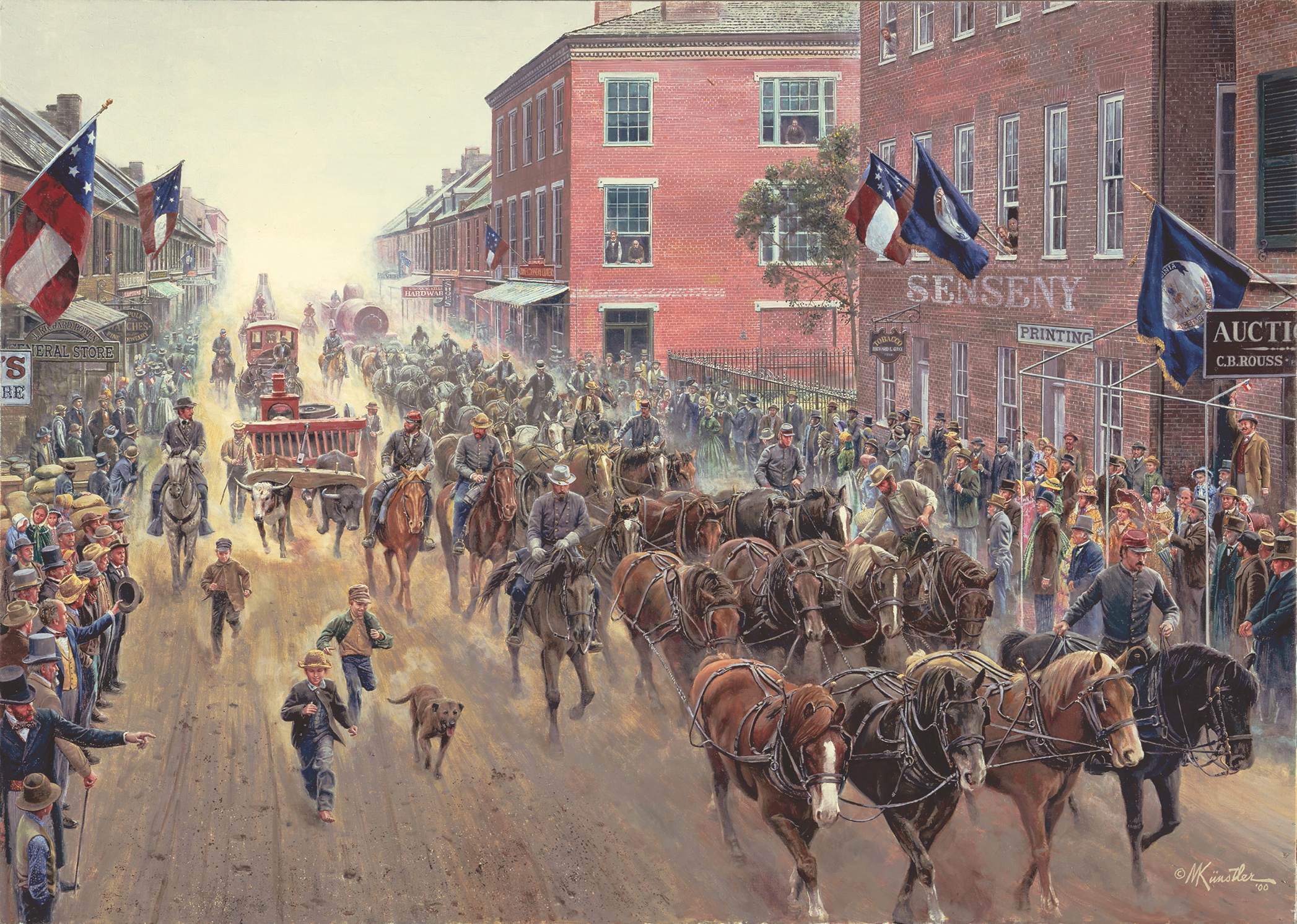

As a resident of Winchester, Virginia, she was in a prime position to experience and record much of it. Located in the fertile Shenandoah Valley, the so-called “Breadbasket of the Confederacy,” Winchester changed hands numerous times during the conflict. Over the four years of the war, several battles, raids and skirmishes took place in the immediate area. As historian Chris Fordney once noted: “No town heard more of the war’s rumblings than Winchester.”

Meet Cornelia Peake

Cornelia Peake was a lifelong Southerner, born into a slave-owning family in Alexandria, Virginia. In 1847, the 24-year-old Cornelia married Angus William McDonald, a widower 23 years her senior. A prominent Virginian, and West Point graduate, Angus had a resume that included stints as a fur trapper and trader, attorney, state government official, and land owner. He had married once before, fathering nine children before the death of his first wife. In the 14 years before the start of the war, Angus sired nine more with Cornelia. After living in various places, the family settled into “Hawthorne,” an impressive house in Winchester, while Angus practiced law.

Early in the war, Angus served as a colonel in the famed Stonewall Brigade. The following year, he reported to Richmond as an adviser in the Confederate War Department, leaving Cornelia and their children, along with three servants and two slaves, in Winchester. Before departing, Angus instructed her to keep a diary, in order to record local developments.

REluctant, then passionate diarist

Prior to the war, Cornelia had given no thought to keeping a personal journal. When she took on the task, however, she did so with a vengeance. From the first entry in March 1862, to her last in late 1863, she reports accurately and in detail on events transpiring around her and her family. Her writing style is often eloquent: “I had a heart for sorrow, and it ached with a ceaseless pang for the country as well as for my own griefs.” Writes editor/biographer Minrose C. Gwin: “She tells exactly what it was like to be a middle-class white southern woman during the Civil War, what it meant to defend a household against numerous attempts (eventually successful) to take it over …[ and] how it felt to be left behind to cope and wait.”

In matter-of-fact tones, Cornelia recorded a seemingly endless litany of horrific experiences. Shortly after a nearby battle, while tending her garden, she stumbled across a human foot. And on Christmas 1862, she wrote of how hundreds of Yankee soldiers broke into her home, smashing the windows and stealing her family’s food out of the oven and off the table.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

From the beginning of hostilities in and around Winchester, Cornelia volunteered to tend the wounded. On one occasion, she described the shock of being asked to bathe the wound of a man whose eyes and nose had been blown away. In fleeing the room in distress, “my dress brushed against a pile of amputated limbs heaped up near the door.”

In time, however, even the constant presence of men mutilated or killed in battle failed to elicit an emotional response: “I heard someone describing the pitiful sight of a school boy brought in mortally wounded….[B]ut I had seen the fair dead faces of our boys, in the early days of the war, when all were eager for the fray … so it was no new thing to me.”

No Words

There were circumstances, however, when Cornelia possessed neither the objectivity nor the ability to write. On Aug. 23, 1862, her youngest child, 10-month-old Bess, died in her arms of an undetermined illness. Unable to write for weeks, in late September she finally entered, “Two months since I wrote a line, and oh! The sorrow they have left me. They have taken away my flower. My sweet blue-eyed baby has left me.” She described the child’s death in detail, adding, “I felt as if my heart was lead, I still held her but could see or feel nothing ….” Cornelia mentioned Bess often in her writing — “Morning, noon and night I think of her” — affirming her faith in a God that will raise up and “restore my precious handful of dust as beautiful…as before ….”

Cornelia was very much a product of her time and culture, and her journal was not without its contradictions. While she could express sympathy for the young Union privates (“Some of them are to be pitied, they are forced into the army … and hate the service”), she never lost her sense of loathing for the Federals in general: “To day … a grand review of dirty Yankees took place ….”

Another example of her ambivalence was in the occasional mention of slavery. She purported to loathe the institution: “I never in my heart thought slavery was right … and daily witnessing what I considered great injustice to them, I could not think how the men I most honored and admired, my husband among the rest, could constantly justify it … [and] say it was a blessing to the slave, his master, and the country ….” And yet, in the same paragraph, she wrote, “[E]ven now I say it with shame, that the renewal of the slave trade would be a blessing and benefit to all, if only the consent of the world could be obtained to its being made lawful.”

Leaving Hawthorne

By late July 1863, with the Federals poised to retake control of Rebel-occupied Winchester, many residents fled in haste. Cornelia loaded a wagon with her possessions, and with her remaining children, left Hawthorne forever, to take refuge in Lexington, Virginia. Angus managed to visit them from time to time, but even he was not spared suffering. Along with their teenage son, Harry, he was captured the following summer. Harry managed to escape, but the debilitated Angus was kept manacled in a dank cell, in solitary confinement.

After his release months later, Angus sought to return to his family in Lexington; he never made it beyond Richmond. His already precarious health had suffered a devastating blow in captivity, and he died on Dec.1, 1864. Cornelia knew only that her husband was in Richmond, and she raced to be with him. Unaware he had died the day before, she walked into the house where he had been staying: “[T]he first object I saw was my husband’s corpse, stretched on a white bed with a large green wreath around his head and shoulders …!”

Widow’s Words

Even after Angus’ death, Cornelia maintained her diary, although the logistics were often challenging, and at times impossible. “Days pass,” she wrote, “and the promise of a daily record not kept. Cares and heavy tasks all day, and when night comes such weariness that I can only go to bed without touching pen or paper.” Also, as she later stated, writing paper was scarce under the current circumstances, and she took advantage of every available space — including “some on blank leaves of old account books, and some between the lines of printed books.” Sadly, when she and her family were forced to flee Winchester, several months of her entries were lost. She later rewrote them to the best of her impressive memory—and at this point, the work became a hybrid, as much memoir as journal.

The years of conflict exacted a terrible toll on Cornelia. By war’s end, she had lost her husband, a stepson, her sister and her youngest child. In addition, she and her family had endured humiliation, hunger, penury and ultimately homelessness. In 1875, after adding reminiscences about the war, she handwrote a copy of her nearly 500-page manuscript for each of her surviving eight children to ensure they had a personal record of the war years. A fine artist, she had illustrated her diary/memoir with vivid illustrations. Sixty years later, one of her sons edited and published her book under the title, “A Diary With Reminiscences of the War and Refugee Life in the Shenandoah Valley, 1860-1865.”

For nearly a decade after the surrender, Cornelia made Lexington her home, supporting her family by giving drawing lessons and selling her art. She later moved, along with most of her children, to Louisville, Kentucky, where she died at her daughter’s home, at the age of 86.

Cornelia was just one of a handful of women whose writings and defiance in the face of Union occupation earned them the sobriquet “Devil Diarists of Winchester.” So vexed was Union Maj. Gen. Robert Milroy by both their writing and their constant resistance that he fumed: “Hell is not full enough. There must be more of these Secession women of Winchester to fill it up.”

But Cornelia’s journal is remarkable in itself, in that it addressed both the world at war outside her door and the effect it had on her and her family. As a personal record of the war on the Southern home front, it remains timeless. Writes Gwin, “In the midst of a culture of war, McDonald’s writings show the effects of that culture on white women and children, slaves and former slaves, southern landscape, and southern life.”

Ron Soodalter writes from Cold Spring, N.Y.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.