Decades after soldiers were wounded, bits of lead showed up in X-rays, or simply appeared

In the decades after he was shot at Gettysburg, William Eckert wasn’t troubled much by the Confederate bullet that lodged near his right shoulder. Then one day in the summer of 1905, the Union veteran from New Jersey felt a sharp pain in his left ankle. It must be that dastardly piece of Rebel lead, he insisted to skeptics. But how could that bullet make such a circuitous journey through a human body?

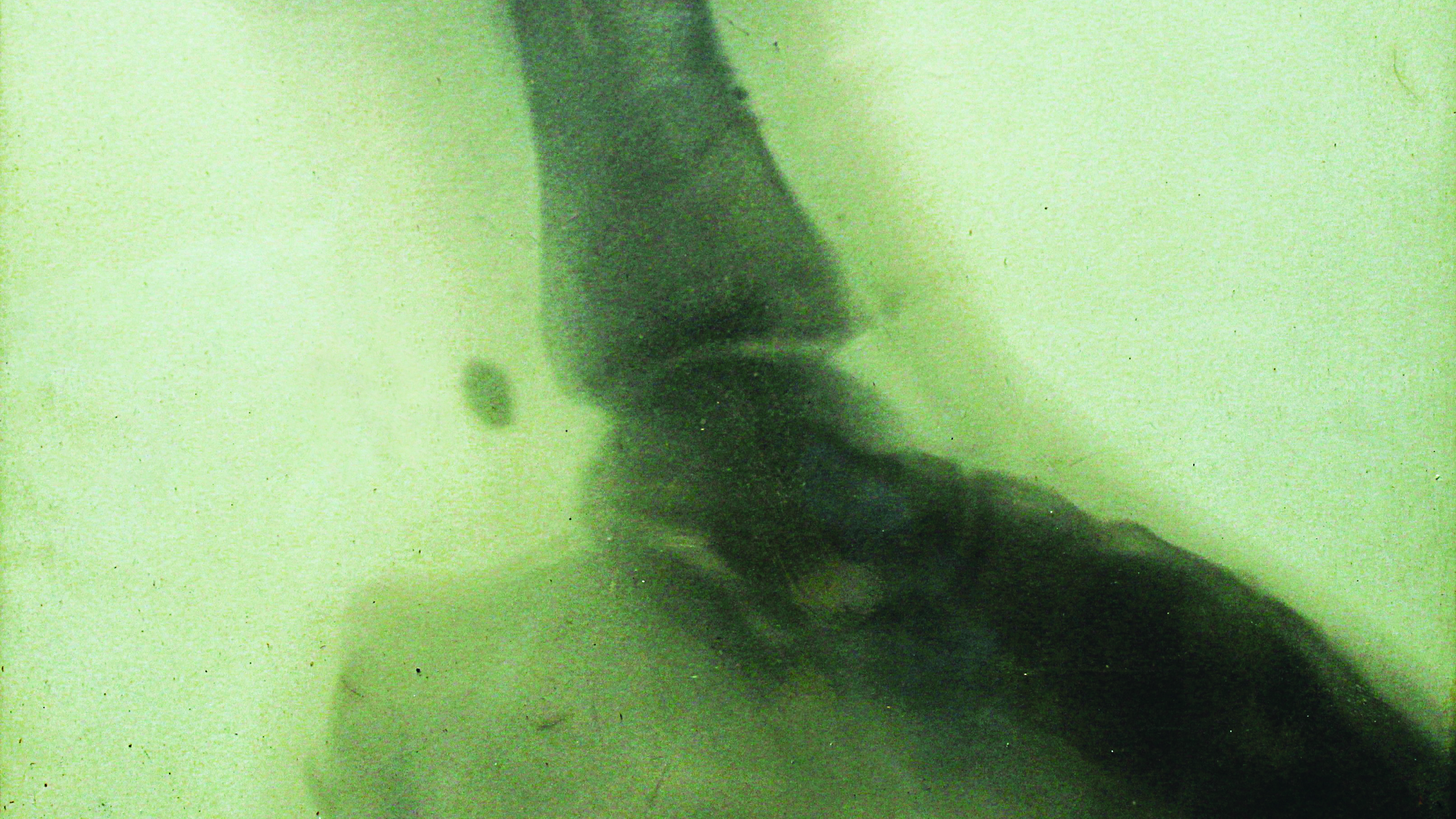

The ankle was examined by X-ray, a relatively new technology. The result: Eckert, incredibly, was correct. A bullet was indeed lodged in a mass of veins in his left foot.

“In all my experience,” the family physician told a newspaper reporter, “I never met with so strange a case. Had the bullet traveled down Mr. Eckert’s right side there would have been nothing unusual about this case. How it traveled around to the left side is a mystery that no medical man or surgeon probably will ever be able to account for.”

The story might not be as unbelievable as it seems: In 1924, an X-ray of Union veteran Joseph P. Reed revealed a bullet in the small of his back—it had entered his shoulder during the war. “Civil War Bullet Tours in His Body,” read the headline in the New York Daily News.

Eckert and Reed were hardly the only soldiers who carried a piece of battle lead in their bodies for a lengthy period after the war. Other strange bullet tales would surface, including times when enemy lead was dislodged by sneezing, wheezing, and—yikes!—even by self-surgery.

In the summer of 1862, 15-year-old Sidney G. Cooke ran away from home and enlisted in the Union Army, only to be tracked down by his father and brought home to New York. The following year, Horace Cooke reluctantly gave his son permission to become a private in the 147th New York Infantry.

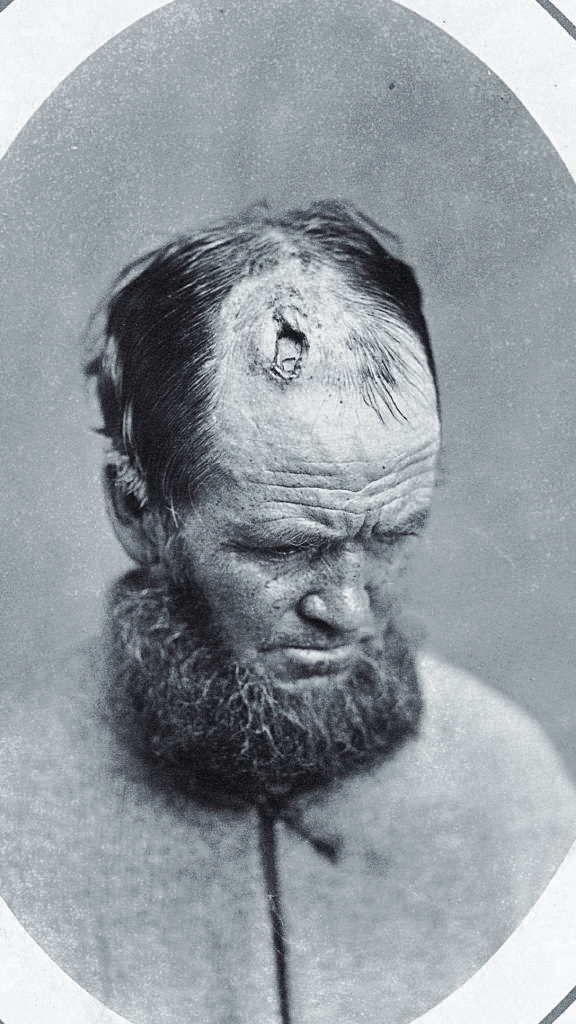

Sidney Cooke suffered a thumb injury at Gettysburg from an exploding artillery shell that killed a comrade. Then, at the Wilderness in early May 1864, he was struck in the head by a bullet. Left for dead, Cooke was discovered in the dark on the battlefield by a Confederate who was searching for his brother. Cooke was still clutching a rifle.

Revived by a sip or two of whiskey, Cooke was carried by the enemy soldier to a Confederate camp, where his wound was dressed, but the bullet was not removed. Cooke’s health rapidly improved, and after he was paroled, he rejoined his regiment. But plagued by a severe cold, Cooke was wracked by a 10-day sneezing fit. A particularly severe sneeze stunningly dislodged the Wilderness bullet, which somehow had moved into Cooke’s nasal cavity.

Cooke, who kept the bullet as a souvenir, survived the war, and eventually moved to Kansas, where he managed a home for Civil War veterans in Leavenworth. He evidently lived a charmed life: In 1917, while he was governor of the soldiers’ home, three disgruntled Spanish-American War veterans placed an explosive device at Cooke’s residence there. When the bomb exploded, the Civil War veteran was stunned and suffered cuts from flying debris. What man’s weapons couldn’t do, Mother Nature could: Cooke died in 1926 when he was 80.

Decades after the war, a sneeze also dislodged a piece of lead from the nose of 6th North Carolina veteran Calvin C. Cook, who had been shot in the head at Gettysburg. According to a newspaper report, in the winter of 1915-16, nearly 53 years after he had been wounded, Cook blew his nose “with uncommon vigor and out rolled his souvenir of the greatest battle of the Civil War.” The veteran’s nasal trouble disappeared when the “bullet”—perhaps a large piece of buckshot—rolled out.

For more than 30 years, a bullet was lodged somewhere in Union veteran Caleb Muir’s cranium, a wound suffered during Phil Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. He was plagued for decades with what was believed to be consumption, or tuberculosis, so much so that “grown men [in Four Corners, N.J.] remember that Mr. Muir was supposed to be dying when they were children,” a local newspaper reported. In early winter 1907, a .28-caliber bullet popped out of the sickly man’s mouth during a coughing spell. Muir’s health rapidly improved, and in only a few days he regained eight pounds.

In 1912, the Philadelphia Inquirer published a story about veteran Francis F. Rogers that, if true, is a real head-scratcher: “Rebel aim was accurate enough to bore four holes in his head and pour eleven other leaden pellets into different parts of his body” at Antietam in September 1862. Army surgeons reportedly removed 11 “bullets” from Rogers’ body at the time, but were wary of removing the lead in his head.

And so he lived on, seemingly unaffected.

Sometime in the 20th century, one of the “bullets” fell out of his head onto a table while he ate dinner. Later, another bullet dropped from his noggin to the floor while he was talking with another man. A third bullet “came from its hiding place” while he was sleeping. Rogers discovered it on his pillow. “Rebel Bullets Fall From Head,” the Philadelphia newspaper’s headline blared.

Rather than operate to remove the fourth bullet, “plainly seen” in Rogers’ forehead, doctors decided to let nature run its course. In 1915, the “rugged, little man” proved to be mortal after all: He died at 95 from injuries suffered from a fall from a hospital bed.

Perhaps Civil War veterans were simply a tougher breed.

At Antietam on September 17, 1862, Captain Henry R. Jones of the 8th Connecticut was shot through the shoulder, the bullet embedding in his clavicle. He underwent a series of operations, but the mini-

missile—which caused “intense suffering”—could not be removed.

In the summer of 1903, Jones felt something hard protruding through his shoulder. Amazingly it was the bullet that had caused him so much grief. He removed the 1-ounce projectile himself with pincers.

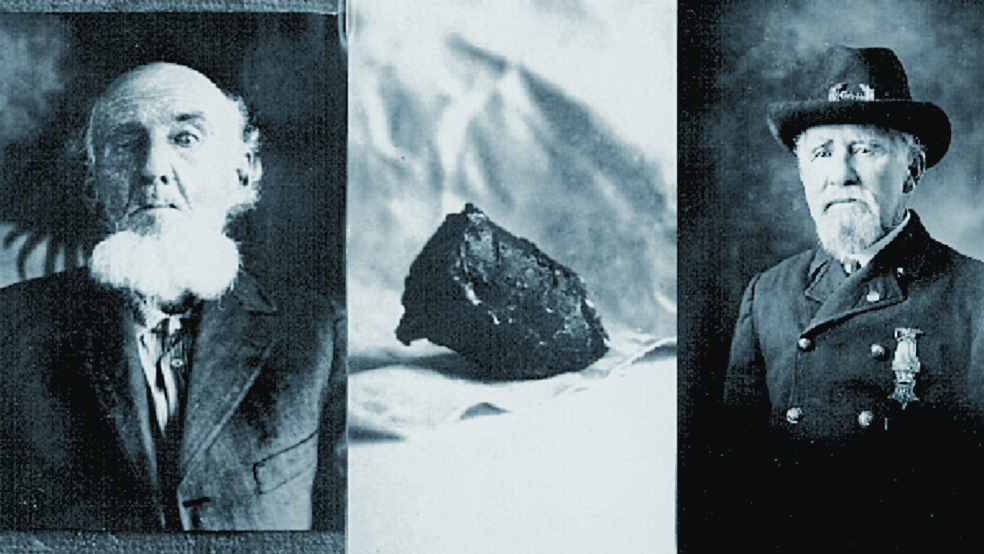

Bela Burr, a private in the 16th Connecticut, was wounded in the shin and ankle at Antietam during his rookie regiment’s disastrous attack in the 40-acre cornfield near Burnside Bridge late in the battle. His younger brother, Francis, was mortally wounded through the groin in the assault, and the brothers lay in the cornfield—no-man’s land immediately after the battle—for 40-plus hours until they were carried away for medical care.

A late–19th century X-ray showed the misshapen metal embedded near the joint of Bela Burr’s ankle. It was removed by a doctor and saved by the veteran, who donated it to the Grand Army of the Republic Hall in Rockville, Conn.

A newspaper editor and publisher after the war, Burr sought a government pension in 1908, prompting the Courant to trumpet his cause:

“Read the simple story of his experience and ask yourself if you think $30 a month paid to him in his old age is a national extravagance. Money can never measure the debt we all owe to the true heroes of the great struggle, among whom the quiet and unassuming men like Burr are as truly entitled to be counted as the great generals whose names are part of history.”

The case of Union veteran William B. Smallridge may be unique. In early September 1861, the private and his comrades in the 3rd West Virginia were ambushed by bushwhackers near the Calhoun County line in what became West Virginia in 1863. A round ball—about .32-caliber—sliced through Smallridge’s lung and came to rest in his chest.

The slow-moving bullet failed to knock Smallridge down, but he was temporarily blinded. Carried to a house, he was examined by a regimental surgeon who said the wound was fatal. “On being told that he must die, Mr. Smallridge actually laughed at him,” according to a West Virginia newspaper, “and told them he would do no such thing.”

Smallridge, who never rejoined the Army, recovered at home in Glenville, W.Va., and endured for 37 more years with enemy lead in his chest. While on his deathbed in 1898, he asked his doctor to perform an autopsy to determine where the bullet rested. Stunningly, it was found in the left ventricle of Smallridge’s heart.

The doctor who performed the postmortem operation apparently kept the portion of the heart with the bullet preserved in alcohol in his office.

But perhaps the all-time Civil War bullet tale involves a trip to the dentist. In 1922, a Confederate veteran from Mississippi complained of a toothache. During the war, the man—unnamed in a contemporary newspaper account—had been shot in the head, but surgeons could not locate the bullet. His tooth was extracted during the dental exam. Several days later, a bullet popped up through his gum where the tooth had been removed.

Maybe he simply had to grin and bear it.

John Banks writes from Nashville, Tenn.

_____

Casualty Count

Other Civil War bullet stories peppered the pages of American newspapers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries:

In Philadelphia, Union veteran A.J. St. Clair removed a bullet from his leg with his pocketknife 31 years after the war ended. A newspaper reported the story under a headline that read, “His Own Surgeon.”

Confederate veteran T.G. Hamilton was wounded in the back in Atlanta in 1864. “Skilled physicians” failed to locate the lump of lead over the years, and the ball gave Hamilton “a great deal of trouble,” one newspaper reported. When he awoke one morning, he discovered the bullet lying in his bed. Finally free of pain, Hamilton kept the bullet for the rest of his life.

Shortly before his death in 1906, Henry L. Mills, a nephew of Robert E. Lee who served with the 50th New York Engineers, coughed up a piece of wartime buckshot that had lodged in his lungs.

In 1923, Union veteran Ben Zellner, who had been wounded in the hip at the Battle of Cedar Creek, Va., in 1864, experienced severe pain in his hip. An X-ray revealed a bullet—Zellner had thought the wound was the result of a bayonet thrust.