By R. Thomas Campbell McFarland

2019, $49.95

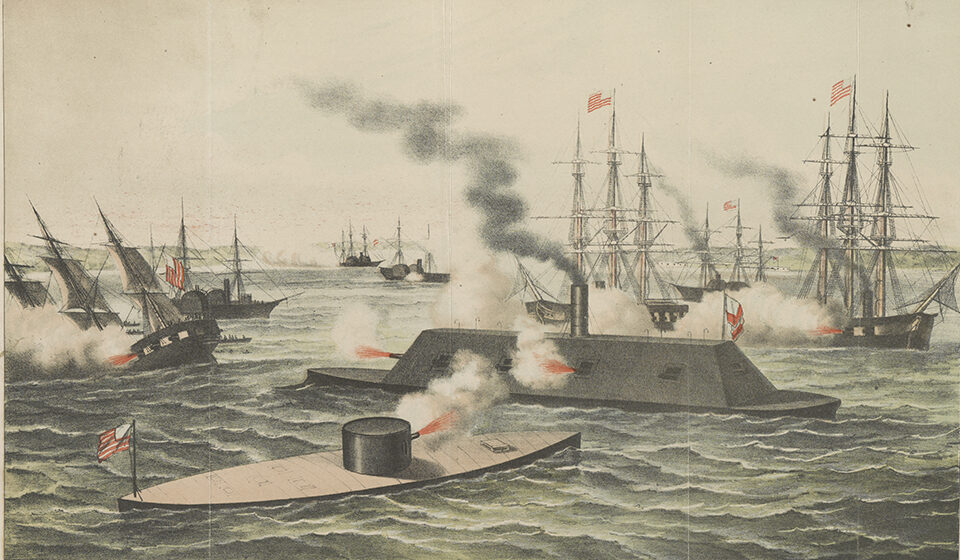

This is a well-written and solidly researched account of the Confederacy’s effort to compete with the North in the construction of ironclads. As Union Admiral David Dixon Porter wrote after the war, the South did everything possible to be successful, and persevered despite the absence of crucial materials and experienced shipbuilders and shipyards. The shortcomings and delays this caused were a source of constant frustration for the Confederate government, Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory and his admirals, and the ship designers themselves, such as Gilbert Elliott, creator of the daunting CSS Albemarle.

By 1865, the Confederacy had built 34 iron-armored warships, with only 25 placed in service. In comparison, the North constructed at least 50 Monitor-class ironclads, including CSS Virginia’s famed opponent, Monitor.

Despite the odds, the Confederates had some notable successes, Albemarle in particular. Elliott’s ironclad singlehandedly raised havoc against the Union Navy outside Plymouth, N.C., in April 1864 and then again in Albemarle Sound a few weeks later.

Albemarle was destroyed in October, not in action but as the victim of a daring raid by Union Lieutenant William Cushing, who used a spar torpedo to wreck the ironclad in the dark while it was anchored.

Except for Albemarle, no Rebel ironclad was sunk or demolished by enemy action. Some, such as Virginia in May 1862, were destroyed by their own crews rather than allowing them to fall into Union hands. CSS Atlanta, though, was captured and converted into a Union ironclad. Campbell delivers groundbreaking analysis and insight on personalities who made a significant difference.—Reviewed by David Marshall

[hr]

and the Inside Story of the Union War

By Carl J. Guarneri

University Press of Kansas, 2019, $39.95

Walt Whitman described Charles A. Dana as “a straight, trim-built, prompt, vigorous man, well-dressed with strong brown hair, beard, and mustache, and a quick, watchful eye. He steps alertly by, watching everybody…a man of rough, strong intellect, tremendous prejudices, firmly relied on, and excellent intentions.” A successful journalist, Dana would have an outsized impact on the Civil War by bringing the qualities ascribed to him by Whitman to further the Union cause, a cause in which he passionately believed.

The only previous full-length biography of Dana was written in 1907. Carl Guarneri remedies this void with an empathetic, but not uncritical, biography of the Civil War’s quintessential “inside man.” In straightforward prose, Guarneri quickly summarizes Dana’s early years, culminating in his job as managing editor of the New York Tribune. Dana would reclaim his place as an outstanding newspaperman after the war as editor of the New York Sun.

After Dana and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton crossed paths, the journalist’s Civil War legacy began to grow. Stanton concluded that Dana was a man on whose judgments he could rely. Dana became Stanton’s trouble shooter, beginning with an assignment to report on questionable contracts being issued by Union quartermasters in Cairo, Ill.

But Dana’s service to the nation took a gigantic step forward when Stanton sent him west in 1862 to “report to me every day on what you see.” Dana’s target was Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, then in the midst of his campaign to capture Vicksburg, Miss., and split the Confederacy. Washington was rife with unfounded rumors of Grant’s military incompetence and his occasional public drunkenness.

Guarneri leads readers through Dana’s undisguised infiltration of Grant’s inner circle. Guarneri maintains, “His dispatches kept Stanton and Lincoln informed about Grant’s movements, explained his plans, and projected confidence in his success.” He probably saved Grant’s career at this critical juncture because “he saw Grant as the fighting general the Union desperately needed, and he committed himself to championing his cause with Stanton and Lincoln.”

After that, Dana showed up wherever the action was hottest. When William Rosecrans got his Army of the Cumberland bottled up in Chattanooga after the Union disaster at Chickamauga in September 1863, Dana’s reports on the situation helped get “Old Rosey” relieved and Maj. Gen. George Thomas put in charge.

When Lincoln and Stanton needed information on the progress of Grant’s Overland Campaign, Dana was ready to ride at a moment’s notice. Guarneri goes so far as to conclude that “Dana called the shots as he saw them without fear or remorse, and his dispatches to Stanton and Lincoln hastened the Union’s day of vindication.”

Guarneri’s insightful analysis and scrupulous research more than justify his conclusion that the Civil War “harnessed [Dana’s] prodigious energy and ambition to the dual cause of preserving the Union and ending slavery.” “Dana’s insider role and his unflinching judgments,” Guarneri maintains, “made him controversial, then and now.”—Reviewed by Gordon Berg

[hr]

Infantry in the Civil War

By Joseph C. Fitzharris

University of Oklahoma

Press, 2019, $34.95

In Volume 67 of the “Campaigns and Commanders” series, Joseph C. Fitzharris looks at the unusual history of the 3rd Minnesota Infantry. In 1861, Minnesota was still regarded as a frontier state with a white population of only 169,395. Still, its governor, Alexander Ramsey, and the populace were eager to display their state’s best. After the Union debacle at First Manassas, Ramsey sought the War Department’s permission to raise a third regiment for the Army. Soldiers of the 3rd Minnesota distinguished themselves from other Union troops by their appearance, their discipline, and good behavior. Attacked by Nathan Bedford Forrest at Murfreesboro, Tenn., on July 13, 1862, the main body of Minnesotans used rifle and artillery fire to wreck the 2nd Georgia Cavalry’s charge. Unfortunately for the regiment, the 23rd Brigade’s commander, Colonel William Duffield, was wounded, taken prisoner, and then surrendered components of his brigade to Forrest, including Colonel Henry C. Lester’s 3rd Minnesota.

After that ignominious disaster, the 3rd was reconstituted and restored to a first-class fighting unit. Its return to combat, however, was closer to home in the Dakota War, during which the 3rd broke Chief Little Crow’s band at Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. The 3rd later supplied the most officers for U.S. Colored Troops units. For example, when formed in 1864 the 5th Arkansas Infantry (African Descent), renamed the 112th USCT, was commanded by Lt. Col. John G. Gustafson, formerly of Company D, 3rd Minnesota, along with four captains and 10 lieutenants. Although the 3rd Minnesota did not suffer many battle casualties, 239 of its troops died of disease.

Fitzharris draws on a history of the regiment that had been left behind virtually in pamphlet form, fleshing it out with detailed looks at the unit’s commanders and other personalities. The result is another satisfying addition to researchers interested in Civil War regimental histories.

[hr]

What Are You Reading?

Bryan Cheeseboro

Historian,

Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington, D.C.

How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War

By Gary W. Gallagher

University of North

Carolina Press

2008, $45

I recently finished Causes Won, Lost and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War by Gary Gallagher. It’s an important book because many people get their history from movies instead of nonfiction books; or, better yet, by doing their own research. Gallagher’s book makes you wonder if filmmakers are obligated to present history accurately. What would really be interesting to discover is what the soldiers, civilians, and enslaved people who actually lived through the war thought of Hollywood’s depictions of their experiences. Did any person who was enslaved ever see Gone With the Wind? And if so, what did they think of it? I doubt many (or maybe any) ever saw it, but I’m guessing they wouldn’t have been impressed.

[hr]

LSU Press, 2019, $45

Allison Johnson’s work on Civil War wounds began as her doctoral dissertation. The challenge is to reformulate a dissertation’s content into a narrative accessible to an audience beyond knowledgeable academics and make it a useful contribution to Civil War historiography. Here, readers may disagree on the degree of Johnson’s success.

Regarding her narrative clarity, Johnson asserts her methodology presents “a Civil War that is embodied, individualized, and fundamentally written by closely engaging with print culture, the primary means by which Americans assessed the conflict and contributed to a polyvocal, corporeal, and multimedia record of the war.” Hopefully, general readers will understand that she read a lot of newspapers and magazines because people in the Civil War era often recorded their impressions of the war in them.

Johnson further contends that current historiography fails to adequately analyze “the significant role of print culture documenting the war’s effects on individuals and their bodies in the national undertaking of recording, understanding, and remembering the conflict.” By focusing on newspapers and periodicals, she argues for nothing less than “a reorientation of the Civil War canon.” It is her focus on literary and artistic representations of the body that allows Johnson to add an interesting perspective on the war’s impact without completely reorienting interpretations of the conflict.

Johnson amply documents her assertion that “bodies pervade Civil War print culture.” But it is over her choices of “body-centric” examples and their overall importance to understanding the war’s effects that attentive readers may differ. In her first chapter, the body in question isn’t even a real one. It is Columbia, the traditional symbolic personification of the United States. Her periodical survey “reveals that the lived experiences of real women, not just their suffering, were central to the journalistic and literary narrative of the conflict” and the changing interpretations of Columbia parallels the war’s brutal evolution. Johnson knows that the contribution of women in the Civil War is now well established. She does expand on this genre by arguing that “the symbolic feminine inserted the lives, bodies, and experiences of real women into public discourse and the literary and visual record of the conflict.”

Johnson’s powerful chapter on the varied depictions of black soldiers persuasively argues that it was in military service that the “transformation of black men from objects to subjects, from slaves to soldiers” became “one of the central tropes of Civil War popular literature.” Rather than being merely the passive recipients of white abolitionist benevolence, Johnson argues that “black soldiers earned citizenship, franchise, and manhood through participation in the conflict that would determine the fate of their people.” Accounts and illustrations of black soldiers fighting and dying alongside their white comrades change the paradigm. “The onus is on readers,” Johnson maintains, “to recognize that black men have redeemed their race and earned the blessings of liberty.”

There is a chapter on the writings and penmanship contests of the “left-handed corps,” men whose right arms were amputated during the war. Her conclusion that “the writings of the Left-Handed Corps constitute a unique body of disabled literature and are therefore invaluable cultural artifacts” that offer “new ways of conceptualizing heroic masculinity and disfigurement” opens an interesting avenue for future research.

Johnson’s innovative approach to the cultural history of the Civil War does offer a valuable contribution to Civil War historiography. If her prose were easier to decipher, more readers would probably benefit from her scholarship.

[hr]

May 19-22, 1863

Steven E. Woodworth and Charles D. Grear, Editors

SIU Press, 2019, $29.50

The capture of Vicksburg after a 47-day siege by Union forces under the command of Ulysses S. Grant is a turning point in the Civil War. What’s not so readily understood is why Grant twice tried to capture the Confederate bastion by direct assault. Five essays compiled here by Steven Woodworth and Charles Grear analyze the two attacks and argue that Grant’s ultimate triumph may have been achieved only after he incurred more than 3,000 needless casualties.

J. Parker Hills’ two essays analyze the attacks on May 19 and 22 from the Union point of view. The May 19 assault, Hills maintains, was initiated because Grant believed that his troops—flushed with success after successfully running under the guns of Vicksburg’s defenses and conducting a successful land campaign—were eager to finish the job. Also, Grant feared the sweltering summer climate of the Mississippi Delta would afflict his men with various diseases. But, Hills argues, “Time was not taken to perform a proper reconnaissance, position troops, establish a mission statement, or prepare an organized, coordinated plan of attack.”

Grant nevertheless ordered a second assault, what Hills calls “an emotional act.” Only one of Grant’s corps commanders, John A. McClernand, disagreed with the decision, and ironically Grant would later hold him largely responsible for the attack’s eventual failure. Hills finds others more culpable. In the morning attack, “Sherman…engaged only one of his forty-one regiments available.” James B. McPherson, Grant’s Third Corps commander, “did somewhat better that morning by engaging five of his thirty available regiments.” McClernand, however, committed 25 of his 30 regiments but became Grant’s scapegoat for this second costly failure—a failure for which Grant never assumed full responsibility.

Woodward focuses on the assault on the Railroad Redoubt, one of the objectives of McClernand’s May 22 attack. McClernand claimed early success at the redoubt and appealed to Grant for support from the other two corps to solidify his gains. Woodworth comes to a different conclusion, contending “McClernand and several of his subordinates had been mistaken about the degree of their success against the [redoubt]. The breakthrough there had never been more than minimal in scale.” To properly reinforce McClernand required more troops than were available at that time and even if they were, Woodworth concludes, “success would not have been guaranteed.”

Waul’s Legion, which defended the Railroad Redoubt, is the subject of Brandon Franke’s essay. Franke contends that it was their desperate defense that “prevented Union forces from establishing a stronghold within their line; as a result, Grant decided to lay siege to Vicksburg, conceding that the city’s defenses were too strong to carry by force.” That’s a mighty conclusion, even for a Texan to draw. But the legion’s casualty report, which numbered 245, including every officer, strengthens Franke’s argument.

Finally, Charles Grear analyzes smaller hometown newspapers in the Midwest to better understand how the folks back home reacted to the assaults at Vicksburg, their opinion of Grant, “and their economic, political, and social responses.”—Reviewed by Gordon Berg

[hr]

In Exposing Slavery, Matthew Fox-Amato uses daguerreotypes and cartes-de-visite—most published here for the first time—and a wealth of explanatory letters to explore how advocates of slavery and the abolition thereof seized upon the new art to advance their respective arguments.

Visual propaganda was, of course, as old as drawing, painting, and sculpting, but photography offered a credible palette: What one saw reproduced exactly on glass, tin, or paper could not lie. Or could it? Southern photographs emphasized the placid order of life on the plantation with well-dressed house slaves, seemingly content with their lot, standing in the wings in family portraits or posing with the children with whose care they were entrusted. Abolitionist photographs, on the other hand, tended to remove the clothing of escaped field slaves to expose the whipping scars. But even the slavers’ photos were prone to backfire because—unlike graphic artwork—they revealed the humanity of their black subjects.

During the war, Union photographers entered the propaganda war with photographs depicting slaves liberated under the guise of confiscated “contrabands,” although images of a black freedmen genuflecting before Yankee liberators or acting as their servants displayed a residual racism visually not dissimilar to that reflected in Southern photographs. The book notes that the blacks themselves objected to the contraband designation, as it still denied them recognition as human beings. Curiously few in the book, however, are examples of what the U.S. Colored Troops did with their newly expanded access to the photographer’s studio where, posing proudly in their uniforms, weapons in hand, they could at last take control of their own images. That aside, Exposing Slavery gives some revealing insights on a somewhat overlooked aspect of ideological warfare.—Reviewed by Jon Guttman

These reviews appeared in the April 2020 issue of Civil War Times.