Soldiers and civilians flocked to see the freakish and fantastic

On the eve of the Civil War, the circus—or “menagerie,” as some shows featuring human oddities were called—was an immensely popular cultural phenomenon across the United States. The 19th-century equivalent of Hollywood and Broadway combined, the burgeoning circus business had taken the antebellum nation by storm. Competing companies would arrive in large cities or even smaller towns, set up their tents, and provide entertainment ranging from exotic animal performances to collections of human curiosities.

In a time of relatively rigid social rules—where drinking alcohol, playing cards, gambling, and even subtle lewdness were all frowned upon in polite company—the circus was considered a mainstream entertainment that allowed audiences to experience the freakish and the fantastic in mostly acceptable ways, and soldiers on both sides enjoyed them before and during the war.

Some fundamentalist critics saw moral danger in the circus, even as they acknowledged the sensational popularity among the public at large. Milo Grow of the Miller Guards, a Confederate unit from Georgia, categorized the place of the circus retrospectively: “St. Johnsbury was one of the more strict villages in the mid-1800s. The straight-laced were objecting to the loosening of morals. They did not object to baseball, roller skating, magicians, circus or exhibitions of war panoramas, but they did object to raffles, lotteries or females reading sketches or declaiming in public.” A citizen of Augusta County, Va., confirmed the wide popularity of the circus even in rural areas: “A circus arrived in town this morning, which brought together a considerable crowd from the country.” The circus also crossed generational lines. “The young folks, and many of the old ones, will enjoy lots of fun at the Circus,” the Delaware County Republican reported.

The American circus traced its roots back to ancient times, the term circus coming from a Latin word meaning circle, and which was first reportedly used in written English by Geoffrey Chaucer in 1380. An earlier form of the circus had been popular in Europe for many years before coming to the New World, and in particular, had been a long-standing social event in England. Some of the best-known acts (dancing horses, acrobatic stunts, even jousting, etc.) could be traced directly to medieval carnival traditions. The menagerie, or display of human oddities, was also popular and traced its roots mainly to 17th-century France, although it, too, dated back to ancient times and the Roman Emperor Elagabalus (reigned 218-222 CE) who had a famous collection of human oddities from around the Mediterranean world.

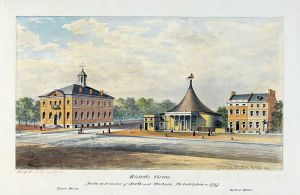

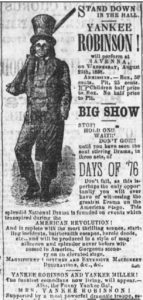

The first known circus in the independent United States occurred in in Philadelphia in 1793 when equestrian John Bill Ricketts set up wooden bleachers around a circular space and dazzled the audience, including President George Washington, with feats of horsemanship. Slowly at first, and then with an ever-quickening pace, the circus and menagerie grew in popularity and was a booming business by the outbreak of the Civil War. This coincided with the rapid expansion of transportation networks, including canals, railroads, coach lines, and macadamized roads. Circus companies were able to travel more quickly and inexpensively, thus allowing them to reach more isolated venues that had hitherto been unable to host performances by large troupes. Many of the companies originated in the Northern states, and as tensions mounted between Northern and Southern factions in the federal government and war became a real possibility, many of these troupes found themselves with difficult decisions about how to handle the Southern stops on their scheduled tours. Many decided to cut tours short; others continued Southern stops, sometimes with unfortunate outcomes. Famous showman Fayette Ludovic “Yankee” Robinson, for example, found his stop in Charleston, South Carolina, suddenly interrupted by John Brown’s raid in 1859. Knowing that his nickname, which stemmed from his upstate New York accent, would make him anathema in the South, he decided to leave abruptly without his tent and gear.

Soldiers on both sides of the war were familiar with the basic nature of the circus and many had attended at least once. Newspaper advertisements in 1860 for the circus “coming to town” are plentiful in both Northern and Southern newspapers. Modern historians have cataloged the myriad circus enterprises of the time—a fairly comprehensive cataloging of Civil War era circuses can be found in William L. Slout’s 2009 Clowns and Cannons—but the performers and managers ranged from local unknowns to international acts, and the list of all of the hundreds (or thousands) of individuals is not likely ever to be completely exhaustive.

Circus troupes continued performing after the war broke out, and even President Lincoln was known to attend. Particularly in the North, large crowds in major cities continued to throng to the “big tent” in spite of other national distractions, like battle reports, or the draft. During the holiday season of 1863, for example, the New York Herald reported, “The Broadway ampitheatre [sic], the Bowery circus and the Menagerie were thronged during the day and evening with children, both of a smaller and a larger growth.” In Washington, D.C., performances occurred regularly to houses packed with soldiers. A Southern gentleman visiting the city by special permit during the war reported that the city was “given over to actors, strong minded women, and quacks who treat special diseases,” and he included among these the “Great American Circus.”

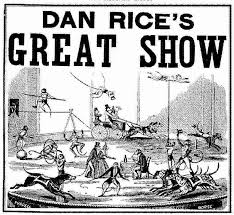

On February 13, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln watched a performance by 2 foot, 11 inch Charles Sherwood Stratton, known by his stage name, Tom Thumb. Lincoln was also well-acquainted with one of America’s most famous clowns, “Yankee Dan Rice,” later the President’s unofficial court jester, who was born in New York City in 1823 and is considered the founding father of American clowndom. Rice’s career before, during, and immediately after the Civil War brought him lasting fame. He also served as the model for the image that would become the iconic Uncle Sam.

Rice was a talented humorist, composer, and all-around entertainer, uniquely popular in both the North and South. In fact, he was not only close friends with Lincoln, but also with Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee, and other prominent Southerners. Rice was so popular and in demand in both North and South that at one point during the war he was making a thousand dollars a week—more than Lincoln, and roughly the equivalent of one and a half million present-day dollars per year.

Rice’s performances in Union and Confederate states during the war were sometimes occasions for ill-feeling as his loyalties were suspect on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. But Rice was indomitable and continued to perform in spite of glares or murmurs. He was well aware of what was going on, however, and he later contributed the funds to erect the first monument to soldiers killed in the war. His popularity provided him with a margin for political error that lesser performers sometimes didn’t enjoy.

Wary Union officers saw the circus as a business where spies and Rebel sympathizers could hide in order to potentially gather useful information or sabotage the Union war effort. Particularly in the Border States, circus performers were often suspected or arrested for sedition or resistance. A Union officer in Cincinnati, a key border city, complained: “I attended the famous circus of Robinson & —— today. In the most exciting portion of the equestrian performance, Mr. Robinson was thrown from his horse. Said the clown (a red, white, and red man): ‘Why is Mr. Robinson like General McClellan? Because, although he has lost his position he has not lost his reputation.’ The ‘butternuts’ clapped their hands, and the pavilion resounded from the hearty applause of hundreds. They were on hand in much force. The ladies here consume themselves in rebel colors.”

In the South, some soldiers were fortunate enough to attend performances even after hostilities broke out; some Northern-based troupes remained at first, and some organic Southern businesses continued. There were also noteworthy regional differences between circus performances—chief amongst them that the audiences were formally segregated by race in the South, seated on separate sides of the arena. The circus acts themselves were similar, although performers and managers literally changed the theme music and the punch lines to jokes depending on which region in which they were performing.

Evidence of circus performances continuing in the Confederacy also comes from the Confederate Congress, which in 1864 updated the code for taxation of performances: “[The] circus shall pay one hundred dollars, and a tax of ten dollars for each exhibition; which tax shall be paid by the manager thereof. Every building, tent, or space, or area, where feats of horsemanship or acrobatic sports are exhibited, shall be regarded as a circus under this act. Every person who performs by sleight of hand shall be regarded as a juggler under this act…” Nevertheless, some Southern states, such as Georgia, saw the circus business practically disappear during the war.

The outbreak of military hostilities created an immediate crisis for traveling troupes in the South that had originated mostly from Northern states. According to historian and circus critic Earl Chapin May, a number of troupes were suddenly “marooned in a hostile Southern land.” Even those troupes fortunate enough to be on the right side of the lines found that business had changed, since anyone who had traveled extensively recently in one region was prone to immediately be a suspect in the other, and sometimes in both.

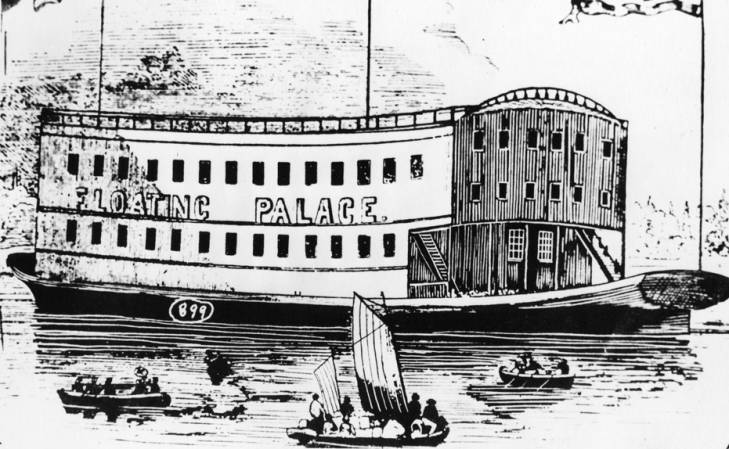

One of the most notable troupes stranded in the South was the Spaulding and Rogers circus with its Floating Palace and accompanying fleet of smaller ships. Dr. Gilbert R. Spaulding, a former pharmacist from Albany, N.Y., and Charles J. Rogers had pioneered the entrepreneurial notion of a circus on water as early as 1852, the entire act being literally self-contained and complete within a sizable amphitheater on board a ship. They also were early pioneers of the rail circus, having completed a rail tour in 1857, which then transferred onto the boats to continue further. While other shows traveled by river and water, wagon, or rail, and performed on land, theirs was perhaps the first major circus to actually travel and perform on the water. The setup on board included facilities for caring for the animals, quarters for staff, and administrative areas, and had the additional benefit of allowing management to never worry about blow downs (the bane of every tent user from any era). The ship reportedly cost $42,000 (roughly $1.4 million today).

While undoubtedly a brilliant business idea, the Spaulding and Rogers floating circus became a victim of the proverbial curse of “wrong place, wrong time.” While in New Orleans after a chain of performances in 1861, the circus’s primary vessel, Floating Palace, was seized by Confederate authorities for use as a hospital ship. To make matters worse, the circus troupe was ordered to leave the Confederacy. There was a decidedly suspicious and sometimes hostile attitude toward most of the Northern circus troupes that were inadvertently caught below the Mason-Dixon Line. Would it not be an ideal place to burrow a spy, who could with legitimate reason travel widely to observe and report back?

Spaulding and Rogers, however, were truly innovative entrepreneurs, and refused to give in to despair. They managed to hire out a smaller steamboat, changed their name to the more judicious title “Dan Castello’s Great Show” (named after a clown with overt Southern connections), and literally “flew the Palmetto flag” while the circus band played “Dixie.”

The Spaulding and Rogers troupe worked its way up the Mississippi, stopping at towns to earn what they needed, making certain that they were, “heartily for Jeff Davis and the Confederacy.” They eventually worked past the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers, where Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was fighting his army closer and closer to the key Mississippi town of Vicksburg. At this time, the troupe literally played for both sides, hoisting the appropriate flag based on which side nominally controlled the area. On one side, they would play Yankee Doodle; on the other, Dixie. When they were safely on the other side literally of the Mason-Dixon line, management conspicuously decided to move the troupe to South America for the next season to escape the foibles of war in America completely.

The remarkable Civil War “escape” of the Spaulding and Rogers Circus was only a sidelight, however, in a long and remarkable business partnership history that dated back to 1848. Among other accomplishments that are often attributed to the team are: first to use quarter-poles in tents, introducing the pipe organ to circuses, inventing knock-down seats, pioneering Drummond lights (also known as “Limelight”) for night performances, using multiple performing teams simultaneously in different locales, and moving an entire circus by rail for the first time. Their acts were gaudy, exaggerated, and fascinating, typified by a carriage holding 50 musicians pulled by 40 horses.

Americans, North and South, fell in love with the circus in no small part due to Spaulding and Rogers; circus terminology and humor also entered the common lexicon in part due to their efforts. In 1863, Harper’s Weekly carried the following joke: “Why do young ladies in love like the circus?” The answer: “Because they have an itching for the ring.” The circus had by this time entered into common parlance. Even the New York Herald could not resist the imagery when questioning the “rage of the radicals” in an 1865 article: “They are, therefore, only watching for developments, in hope of obtaining something that will justify them in arraigning Mr. [William H.] Seward [Lincoln’s Secretary of State] before Congress, and have one of their regular rear and tear scenes, to the amusement of those who like to visit such national circus shows.”

In 1865, the death of a well-known circus elephant even made headlines:

Death Notice: The Manmoth [sic] Elephant “Hannibal,” attached to Thayer and Noyes Circus, which exhibited here in this city last summer, died at Centreville, Pa., on Sunday morning a week aged, it is supposed, about 66 years. He was buried on the spot where he died. He was the largest elephant ever brought to this country. His owners held an insurance upon him for $10,000.

The war, for reasons that aren’t perfectly clear, was also particularly hard on the business of menageries. The Van Amburgh Menagerie, which had traveled the country for 40 years, was the only major operation that continued throughout the war, according to one source. After the Civil War, famous acts like the Ringling Bros. Circus (later to merge into the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus) frequently merged their shows with menageries, monster shows, museums, and other attractions in order to generate ticket sales. James A. Bailey, just a youth when the Bailey Circus plied its trade in the 1860s, is often called the Father of the American Circus, as his post-Civil War partnership with P.T. Barnum spawned the “most famous show on earth,” which included almost all of these elements under one tent.

American’s love affair with the circus continued unabated after the war. A Union officer in Virginia assisting the Freedman’s Bureau complained that newly freed African Americans were wasting their money on “bar rooms and two circus exhibitions.” He also complained about the abuse of alcohol “during one of the circus exhibitions.” But the circus was by this time firmly planted in American society, thanks in no small part to the role it played during the war. Troupes quickly returned to the South in larger numbers, as well. Circuses still tour, though many have decreased the use of animals and focused instead on human performances.

This story from America’s Civil War was posted on Historynet.com on May 12, 2020.