In 1943, when the Second World War had reached its most pitiless intensity, three of the world’s most powerful men—unlikely allies against the Axis onslaught—met together for the first time. In their respective formative years, one had been a soldier, another a murderer, and the third a politician. None fully trusted the others. It was a scene out of Shakespeare perhaps, or even the Bible.

Winston Churchill, the soldier, reasoned in a military frame of mind. He was fair but ruthless, canny and perceptive. Joseph Stalin, on the other hand, quite literally murdered his way to the top of the Soviet Union and, with his hands covered in blood, was suspicious of all and loyal only to the Communist ideal of eventual world domination. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the politician, had an easygoing personality and believed in negotiation in good faith. He thought that deals could always be made between honest men.

The three leaders met in November 1943 in the Iranian capital of Tehran—the Allies had occupied the country since 1941—to strategize the war’s end and beyond. The vivid experiences of each man’s youth informed their differing psyches, personalities, and approaches to the tasks at hand. While that can be said of any decision-maker at any meeting, this was no ordinary meeting. Events put in motion at Tehran would determine Europe’s fate for generations to come.

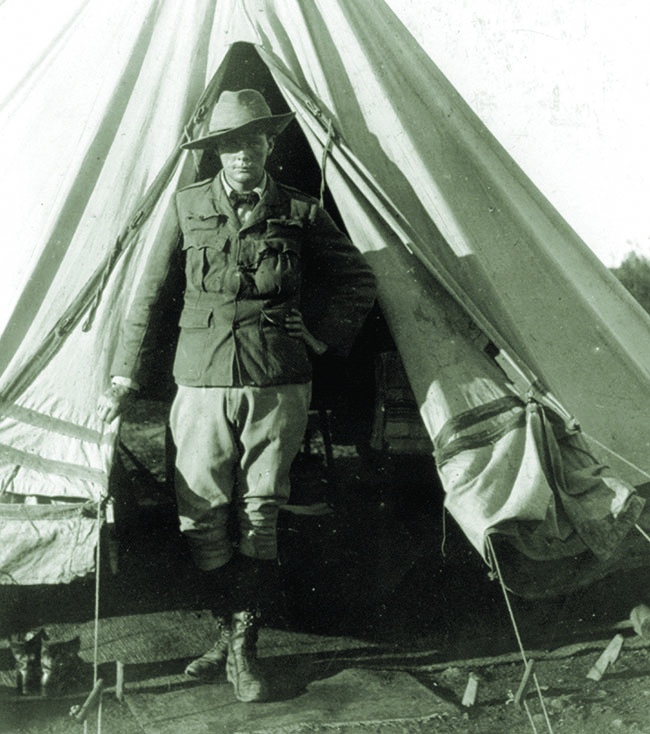

WINSTON CHURCHILL WAS A BRITISH aristocrat who had graduated from the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst in 1894. He later explained that his father had encouraged an army career because he thought young Winston was “too stupid” to become a lawyer. Churchill endured a baptism by fire with immediate combat stints in Cuba and India in 1895 and 1896 respectively and, in 1898, served in the deserts of Sudan with British general Herbert Kitchener’s expedition against an army of 60,000 Islamic fighters. There, on horseback, Churchill saw intense action amid a swarm of sword-wielding Dervishes, shooting them down from his saddle one by one, and remarking later “how easy it is to kill a man.”

In 1899, during Britain’s second war with the Boers of southern Africa, Churchill further distinguished himself, making a dramatic escape as a POW and crossing 300 miles of hostile enemy territory to safety in Portuguese East Africa. He wrote about each of these exploits in the British press, becoming the nation’s best-known and highest-paid war correspondent. This renown, along with his famous ancestral name, he parlayed into a seat in the House of Commons, launching an illustrious government career that ultimately led him to become the country’s prime minister in 1940.

As Great Britain’s head of state during World War II, Churchill led his nation through Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain. By the time of the Tehran Conference, after gains in the Mediterranean and North Africa, Britain stood poised to strike back at Germany.

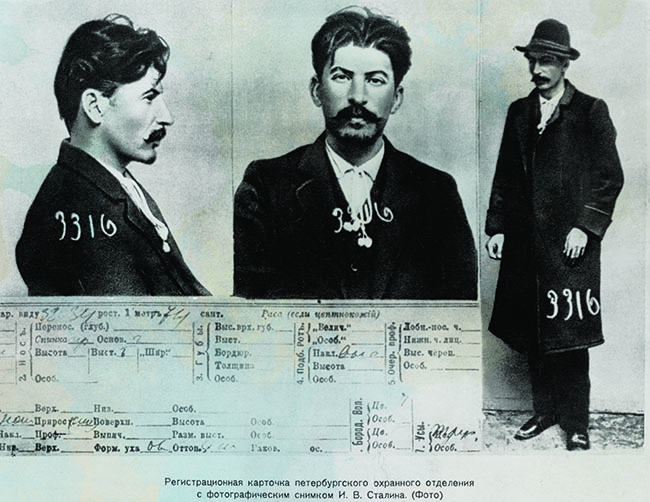

JOSEPH STALIN (born Joseph Vissarionovich Djugashvili in 1878), a peasant, studied for the priesthood until he was 21, when he quit to become a full-time Bolshevik revolutionary.

As a young man, he worked his way up the ranks, organizing bank robberies, bombings, extortion, and murder on behalf of Vladimir Lenin’s fledgling Communist Party. In 1913, at age 35, he began calling himself by a new name, “Stalin,” an apt moniker based on the Russian word for “steel.” After the Russian Revolution of February 1917 toppled the Imperial Romanov family, Stalin became a major functionary of Lenin’s new Soviet government when it came to power that October.

Upon Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin outmaneuvered or assassinated his opponents and became leader of the Communist Party and dictator of Soviet Russia. By World War II, he had caused the deaths of tens of millions of Soviet citizens and “purged”—that is, murdered—thousands of his fellow Communist comrades as well, including hundreds of top-ranked officers in his army.

During the war, Stalin issued infamous orders that called for the immediate execution of any Soviet soldier caught retreating and branded his country’s POWs as traitors. (When his own son Yakov was captured, he was said to have exclaimed, “I have no son!”) But, wisely, Stalin let his generals develop and run the battles and by late 1943 the German army in the east was on the ropes.

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT was born into a wealthy patrician family of Dutch descent that prospered in mansions along the Hudson River near Hyde Park, New York. He was a distant cousin of President Theodore Roosevelt, whom he worshiped.

Roosevelt attended the distinguished Groton School, an Episcopal boys’ academy in Massachusetts. Politics in those days was generally considered an unworthy calling by the upper classes, but the school’s headmaster, Endicott Peabody, believed strongly that Groton men should change that impression and encouraged government service. Roosevelt thrived at school and gained a reputation for his leadership and ability to organize, compromise, and get things done.

He went on to Harvard and Columbia Law School, but soon found himself bored with the legal profession, longing for something different at which he could excel. Politics became the answer. He ran successfully as a Democrat for a place in the New York state senate and, in 1913 at age 31, was tapped for the important federal position of assistant secretary of the navy. Following World War I, Roosevelt had made enough of a name for himself to be placed on the 1920 Democratic ticket as vice president, but the Republicans won.

The next year, tragedy struck when he was permanently paralyzed from the waist down by polio. Undaunted, from his wheelchair, Roosevelt campaigned for and won the governorship of New York in 1928 and, in 1932, was elected president of the United States amid the worst economic depression in the nation’s history. He immediately set about implementing a series of government measures meant to ease the suffering, calling it the “New Deal.”

Through it all, Roosevelt maintained a sunny public disposition and made the working class feel heard. The enemies of progress, as Roosevelt had come to see it, were the bankers, merchants, industrialists, and the moneyed crowd, and so he punished them through taxation and other constraints. In return, the wealthy businessmen branded him a “traitor to his class.”

After war broke out in 1939, the U.S. stayed outwardly neutral—though, through the Lend-Lease program, FDR worked to counter the country’s isolationist tendencies and support the Allies. Officially drawn into the conflict in 1941, the U.S. by 1943 was both at war with the Japanese in the Pacific and adding its considerable might to the fight in Europe.

THE IDEA OF A SUMMIT so these men—known as the “Big Three”—could meet in person to strategize the war had been proposed for some time, but Stalin had always said he could not leave Moscow with Germans at the gates. But at the end of 1943—when the Axis powers had been at war with Britain for four years and with the Americans and Russians for two—Stalin finally consented and the Allies gathered in Tehran for the “Big Three Conference.”

While Stalin trusted no one, he reserved a particular enmity for the British. Since the very beginning of the Russian Revolution 26 years earlier, Churchill in particular had been vociferously anti-Communist, anti-Soviet Union, and—after the Russians signed their short-lived 1939 peace pact with Hitler—anti-Stalin. Churchill now found himself in bed with the very dictator and system he despised, for the simple reason that he loathed Hitler more.

Although Roosevelt and Churchill had developed a close personal relationship even before the war broke out, Roosevelt did not share Churchill’s antipathy toward Soviet Communism. His administration had officially recognized the Soviet Union soon after the president took office. Roosevelt, whose dislike of imperialism was well known, was actually more suspicious of the British. He worried of Churchill’s intentions of keeping Britain’s vast empire after the war—which of course Churchill fully intended to do.

On November 27, 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill arrived in Tehran by airplane from Cairo, while Stalin, who didn’t like to fly, came in from Moscow on his private train. The next morning, on the first official day of the conference, Russian foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov ginned up word of an assassination plot against all three leaders, warning vaguely of German “saboteurs and parachutists,” and declared that the only safe place in Tehran was with the Russians.

American diplomats and security personnel concluded that the purported assassination plot was a hoax to maneuver Roosevelt and others into a place where they could be secretly surveilled but, according to historian Thomas Parrish, the president welcomed the opportunity to “make a positive gesture toward the suspicious Stalin.” [For another perspective on the assassination plot check out Howard Blum’s Night of the Assassins: The Nazi Plot to Eliminate the ‘Big Three’]

So it was that by the afternoon of November 28, the president and his retinue of military advisers, diplomats, translators, and other aides—including his son Elliott, a U.S. Army Air Forces colonel, as attaché—found themselves in Tehran along with the British contingent residing, of all places, in the Soviet embassy. Interestingly, a newly built wheelchair-accessible bathroom adjoined Roosevelt’s room.

AS THE CONFERENCE got underway later that afternoon, it became apparent the Russians would dominate the discussions, mainly to demand yet more supplies—planes, tanks, trucks, guns, rifles, ammunition, and all manner of secondary equipment—from the United States’ Lend-Lease program, but also to implore the other Allies to invade France and create a much-desired second front in the west.

For the British and American diplomats, a different question loomed: what would Soviet policies be after Germany was defeated? It was obvious that if the Red Army continued its successes on the battlefield, it would break through to Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and all the way into Germany itself. Would the Communists remain there to claim spoils, or return to their own boundaries?

The answer came more quickly than anyone thought possible. Stalin surprised Roosevelt before their first official meeting by volunteering that he had “no desire to own Europe,” and that he and his countrymen had “plenty to do at home, without undertaking great new territorial responsibilities.” This was what Roosevelt had wanted to hear and it certainly got things off to a good start, though there were those among the president’s diplomats and military brass who remained skeptical of Stalin’s true intentions.

There were still more pleasant surprises in store. In mid-1943, the U.S. War Department had produced a top-secret strategic assessment stating that the “most important factor the United States has to consider in relation to Russia is the prosecution of the war in the Pacific.” At the rate things were going, the paper said, if the United States alone had to fight a ground war on the Japanese mainland, the costs and casualties would be “immeasurably increased,” and the action might even fail. It was thus imperative, because of their strategic location and powerful military, that the Russians join in the defeat of Japan. Thus far, the Soviets had declined to participate on the grounds that they already had their hands full with the German invasion of their homeland.

Roosevelt, using all of his political expertise, took the lead by summarizing the general war situation in a session late in the afternoon of November 28, concluding with the thought that Europe was and should remain the chief focus, and that the longed-for cross-Channel invasion of France (now dubbed “Overlord”) would take place in May 1944. When this was translated to Stalin, he stunned the conferees by declaring that after the defeat of Germany, the Soviet Union would join the Allies in the war against Japan.

This was music to the military contingent’s ears but, again, some of the more cynical diplomats wondered what price the Communists would want for their services against Japan. Would it be concessions elsewhere? Japanese territory? Japan itself?

The next day, discussions soon turned toward what should be done with Germany when the war was won. Stalin suggested that the country should be dismantled, broken up into parts, so as to never again become an aggressive force. “You will not change Germany in a short period of time,” Stalin declared, citing that country’s aggressions in the 1870s, 1914, and yet again in 1939. “There will be another war with them.”

Roosevelt seemed outwardly sympathetic to Stalin’s position but said that U.S. military planners and diplomats favored turning the country into zones administered by Britain, France, the United States and, of course, the Soviet Union, for a specific period of time, to ensure that a peaceful Germany reappeared.

Churchill, for his part, was uneasy with both plans and more or less demurred. In fact, with his military-oriented mind he secretly wanted a strong Germany after the war as a bulwark against Soviet Communism, which he believed would be the greater threat once the Nazis were defeated. During the discussions, he kept muddying the waters, insisting that the Allies should consider his “Balkans Strategy”—attacking Germany from Italy and the Adriatic, the “soft underbelly” of Europe—in addition to Overlord, but according to Elliott Roosevelt, “It was quite obvious to everyone in the room what [Churchill] really meant. That he was above all else anxious to knife up into Central Europe in order to keep the Red Army out of Austria and Rumania, even Hungary, if possible. Stalin knew it, I knew it, everybody knew it.”

THE EVENING OF NOVEMBER 29 started off with great fanfare and ceremony when, in the name of the English king, Churchill presented Stalin with the fabulous, custom-crafted “Sword of Stalingrad” to commemorate the Soviet victory there 10 months earlier. With tears in his eyes while a Russian army band played the Communist anthem, “Internationale,” Stalin kissed the weapon and handed it to one of his marshals—who managed to drop it on the floor (eliciting a scowl from Stalin that might or might not have had death penalty implications). After FDR and Churchill examined the sword, Stalin held it straight up and declared of his soldiers, “Truly they had hearts of steel,” noting “it was easy to be a hero when you were dealing with people like the Russians”—a fairly obvious reflection considering he had given orders for the secret police to shoot anyone who wasn’t a hero.

Dinner that evening was less convivial, owing to Churchill’s brush with a brandy bottle and his apparent black-dog mood. The Big Three, along with their aides, translators, and diplomats, were dining in the embassy’s Great Hall. After a multicourse dinner, toasts began, led by Stalin, who was drinking vodka.

Churchill had been drinking brandy all afternoon and was conscious of Stalin needling him good-naturedly during dinner. The Soviet premier seemed peeved over Churchill’s Balkans scheme. As Roosevelt’s translator Charles Bohlen wrote afterward, Stalin “lost no opportunity to get in a dig at Mr. Churchill. Almost every remark he addressed to the prime minister contained some sharp edge.”

At length, Stalin rose for what Elliott Roosevelt deemed his “umpteenth toast,” and proposed “the swiftest justice for all Germany’s war criminals.” At least 50,000 German officers must be immediately shot upon capture, Stalin continued, in what the younger Roosevelt called a “jocular fashion.”

At this, Churchill could not contain himself and growled, “The British people would never stand for such mass murder,” adding it was “wholly contrary to our British sense of justice. I feel most strongly that no one, Nazi or no, shall be summarily dealt with, before a firing squad, without proper legal trial.” Stalin then asked for Roosevelt’s opinion, and the diplomatically inclined president replied that, “As usual, it seems to be my function to mediate this dispute. Perhaps we could say that instead of executing 50,000 war criminals, shall we say 49,000?”

Upon hearing this remark, Churchill seemed to become unhinged. He arose from his seat with his famous scowl in a flush, in the process knocking over his brandy glass, and declared again that war criminals “must be allowed to stand trial.” He then staggered out of the room, slamming the door behind him. In fact, he had not gone into the hallway, but had blundered into a darkened cloakroom, where he languished for several long moments before, Churchill later wrote, he felt arms “clapped above my shoulders from behind.” It was Stalin, “grinning broadly, declaring he was only playing.”

“I consented to return,” Churchill continued, embarrassed to have caused a scene, “and the rest of the evening passed pleasantly.”

That might have been so for Churchill, but Roosevelt had unfinished business. He was pleased with himself for goading Churchill. Almost invariably in a trio, at some point two will gang up against a third, and Churchill had been asking for it, Roosevelt thought. “Winston just lost his head when everybody refused to take the subject seriously,” Roosevelt told his son. “He was going to take offense at what anybody said, especially if what was said pleased Uncle Joe.”

But the next morning, November 30, the president—ever the politician—asked to be wheeled through an exchange set up at the embassy for visitors in search of exotic souvenirs. “From among the Persian knives, daggers, rugs,” Elliott Roosevelt recounted, “Father selected a Persian ‘bowl of some antiquity’” as a gift, which he then presented to Churchill at a dinner that evening celebrating the prime minister’s 69th birthday. Churchill, for his part, toasted the American president and their lasting friendship.

THE NEXT DAY, December 1, the final day of the conference, Roosevelt, without inviting or even consulting Churchill, got down to business with Stalin and began discussions on divvying up the countries of Europe after the war.

Roosevelt conceded the fate of Poland to Stalin’s Communist state, along with that of the Baltic countries, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. He blithely explained to Stalin that if the war was still going on in 1944, he intended to run once more for the presidency and would “need the votes of the six million Americans of Polish descent” (there were in fact only three million of these), and so he pleaded with Stalin not to formally occupy the country until after the American election.

As for the Baltic States, Roosevelt observed that they had once been a part of the old Russian Empire and that he had no objection to the Soviets reabsorbing them after the war, provided there would be “some expression of the will of the people, perhaps not immediately after their reoccupation by the Soviet forces, but some day.”

He also seemed willing to concede Finland, which was fighting alongside Germany against the Soviets, but Stalin didn’t want it. He asked only for one of its ports on the Gulf of Bothnia, which was okay by Roosevelt.

Despite the apparent treachery of condemning these European nations to the tender mercies of Soviet Communism, there was a method of sorts to Roosevelt’s seeming madness. First, he told people both within and outside of the U.S. Department of State that these were countries the Soviets could take at will anyway. They were all states in the far north bordering on the Soviet Union, whose provenance was vaguely Russian to start with. The notion was, Roosevelt noted, that if he conceded their occupation to Stalin, the Soviets might not cast an acquisitive eye on the larger, more central European states such as Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the Balkans—even Germany itself. As for Poland, Roosevelt explained that he had no confidence in its government-in-exile anyway, which he said consisted of “landed aristocrats” who intended to rule over a feudalistic system to the detriment of the Polish masses.

Before the conference closed, Churchill could not resist asking Stalin about his territorial claims—the fate of all the European nations his armies were now occupying—after defeating the Germans. The cagey old dictator responded that “When the time comes we will have our say.” It may have been the understatement of the century. (A year later, Churchill met with Stalin in Moscow in an attempt to divide Europe into spheres of influence and salvage as much of the continent as possible from Soviet domination—much as Roosevelt had done as Tehran.)

After the conference was over, Russian foreign minister Molotov asked Stalin which of the two men, Roosevelt or Churchill, he had liked the most. The Soviet dictator shook his head. “They are both imperialists,” he said.

THE TEHRAN CONFERENCE ENDED amicably enough, though not much had been accomplished beyond Roosevelt’s promise to open a second front in the west the following year and Stalin’s pledge to attack Japan after Germany was defeated, along with his claim that he had “no desire to own Europe.” Stalin’s reputation for truth and veracity regarding promises is well known. For the Soviet leader, having luxuriated in nearly 50 years of Marxist dogma, his maxim always remained: “The end justifies the means.”

Churchill, with his soldier’s eye, could see that if the Western Allies didn’t get to eastern Europe before the Russians, it would probably fall to the Communists. In this, the prime minister was perfectly correct, and it was nearly 50 years before his aptly named “Iron Curtain” would rise again.

Roosevelt rarely looked at matters national or international through rose-colored glasses, but his sympathies seemed to lie with the multitudes of Communist Russia. The president failed to see Stalin’s murderous regime for what it was—although, in 1945, toward the end of his life, after Stalin had broken multiple promises made at the next “Big Three” meeting at Yalta, Roosevelt informed a New York Times reporter that “Stalin is either not a man of his word or not in control in the Kremlin.”

Roosevelt likely would have been pleased, however, as Churchill certainly was not, with the dismantling of the vast British Empire following the war. The president had always avowed that nations should have the opportunity to shape their own futures and fortunes and not suffer with interference from abroad. Ironically, the master politician, in his zeal to win over Stalin, helped doom Eastern Europe to just such a fate. ✯