In 1940 Britain desperately needed a submachine gun that could be made for about $10. The Sten gun fit the bill.

ON JUNE 5, 1940, THE SMOLDERING BEACHES AT DUNKIRK, ON THE WEST COAST OF FRANCE, were largely silent. German soldiers, having stormed across Western Europe in less than a month, now milled about the bomb-blackened sands. Over 10 frenetic days, the British Royal Navy and a vast fleet of auxiliary civilian vessels had managed to evacuate more than 330,000 soldiers—all that was left for a fragile but continued resistance to the German juggernaut. Yet the physical evidence of a massive British defeat lay all around. In the last-gasp scramble to escape enemy clutches, British forces had abandoned nearly 2,500 artillery pieces, 85,000 vehicles (including 445 tanks), 75,000 tons of ammunition, 416,000 tons of supplies, 11,000 machine guns, and tens of thousands of other small arms.

Great Britain now faced an industrial as well as a military emergency, compounded by accelerating casualties from the German U-boat campaign, the ongoing neutrality of the United States (its Lend-Lease program would not begin for another year), the expansion of its armed forces through national conscription, and the looming specter of a German invasion. A particularly pressing problem was how to arm Britain’s newly constituted Home Guard, which by July 1940 numbered 1.5 million men. The guards, embarrassingly short of weapons, were sometimes forced to drill with broomsticks, eliciting nervous laughter from the British public. If the country was to survive, its fighting men had to be properly armed.

Fortunately, an unlikely—and unlovely—solution was about to appear. It would officially be known as the Sten gun, though some soldiers would come to call it the “Plumber’s Nightmare” or the “Stench Gun.” By any name, it would prove to be one of the most unusual and ubiquitous weapons of World War II.

BRITAIN’S DISASTROUS CAMPAIGNS OF 1939 AND 1940 MADE AT LEAST ONE THING CLEAR: Its armed forces needed submachine guns. During numerous close-range scraps in Norway and France, British soldiers—almost exclusively armed with .303-inch bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 rifles—had come off worse against German troops armed with 9mm MP 38 and MP 40 submachine guns, which delivered blistering fire at 500 rounds per minute over an effective range of 200 yards. Besides increasing British firepower, submachine guns would also be also ideal weapons for the expanding ranks of auxiliary troops and tank crews who needed compact, easily accessible weapons they could store inside their vehicles.

Through most of the 1930s, the Small Arms Committee of Britain’s Ordnance Board had dallied over acquiring submachine guns, testing several foreign-made types but opting for none. When World War II broke out in 1939, the British government hastily acquired limited numbers of submachine guns by importing Thompson M1928s from the United States and by commissioning the Sterling Armament Company in East London to manufacture its own 9mm Lanchester for issuance to the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. Neither weapon, unacceptably expensive for a wartime economy, solved the problem. What Britain really needed was a homegrown submachine gun that could be produced rapidly and inexpensively and that would tick off all the core tactical and functional boxes. “The most important consideration at the moment,” a member of the ordnance board noted, “seems to be to get some form of machine carbine acceptable to all three services into production as quickly as possible.”

The solution came in December 1940, almost six months after Dunkirk. Harold John Turpin, a senior draftsman at the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield, produced a drawing for a simplified trigger mechanism that had only two moving parts. He then worked closely with Lieutenant Colonel Reginald Vernon Shepherd, the inspector of armaments in the design department of the Ministry of Supply at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, to develop a prototype “street fighting machine carbine” that could be produced with minimal machine tools by unskilled laborers. In just 39 days Shepherd’s designers came up with two working prototypes. After performing well in function and endurance tests, the winning prototype was adopted, on March 7, 1941, as the Carbine, Sten, Mk I. The name Sten, the popular story goes, was derived from the initials of Shepherd and Turpin’s surnames, plus the first two letters of Enfield.

The Sten gun broke all the rules. Basically, it was little more than a steel tube fitted with a barrel, bolt, magazine, recoil spring, and trigger; most of its parts could be made with ultra cheap and fast stamping and welding processes. Only the gun’s barrel and bolt required precision machining. As a bonus, it used readily available ammunition: the 9 x 19mm Parabellum. The simple blowback mechanism fired at a cyclical rate of 550 rpm and was fed from a side-mounted magazine—a direct copy of the Germans’ MP 38/MP 40—to aid prone firing. Weighing seven pounds without the magazine and nine pounds with it, there was no wood anywhere on the gun. With just 59 metal parts, the Sten was purposely designed to be churned out by the tens of thousands. The Mk I initially had some frills—a “spoonbill” flash hider, wooden handguard, and vertical folding foregrip—but these were quickly jettisoned to produce the guns in ever larger numbers. Still, the new weapon proved too complicated, requiring up to 12 man-hours to produce, and by the late spring of 1941 a new prototype, the Mk II, was adopted. British prime minister Winston Churchill visited the test facility at Shoeburyness, Essex, on June 13, 1941, and personally test fired the Mk II.

THE MK II WAS AN UGLY GUN, MORE AKIN TO JUNKYARD OFFCUTS THAN A MILITARY-GRADE WEAPON, with a tubular profile, blobs of welding, and a simple skeleton stock. But that was the point: It was the perfect gun for emergency wartime production. And it was stunningly cheap: each gun cost about $10 to manufacture as opposed to $70 for a Thompson. From start to finish, the Mk II took just five and a half hours to make. The challenge now was to mass-produce it.

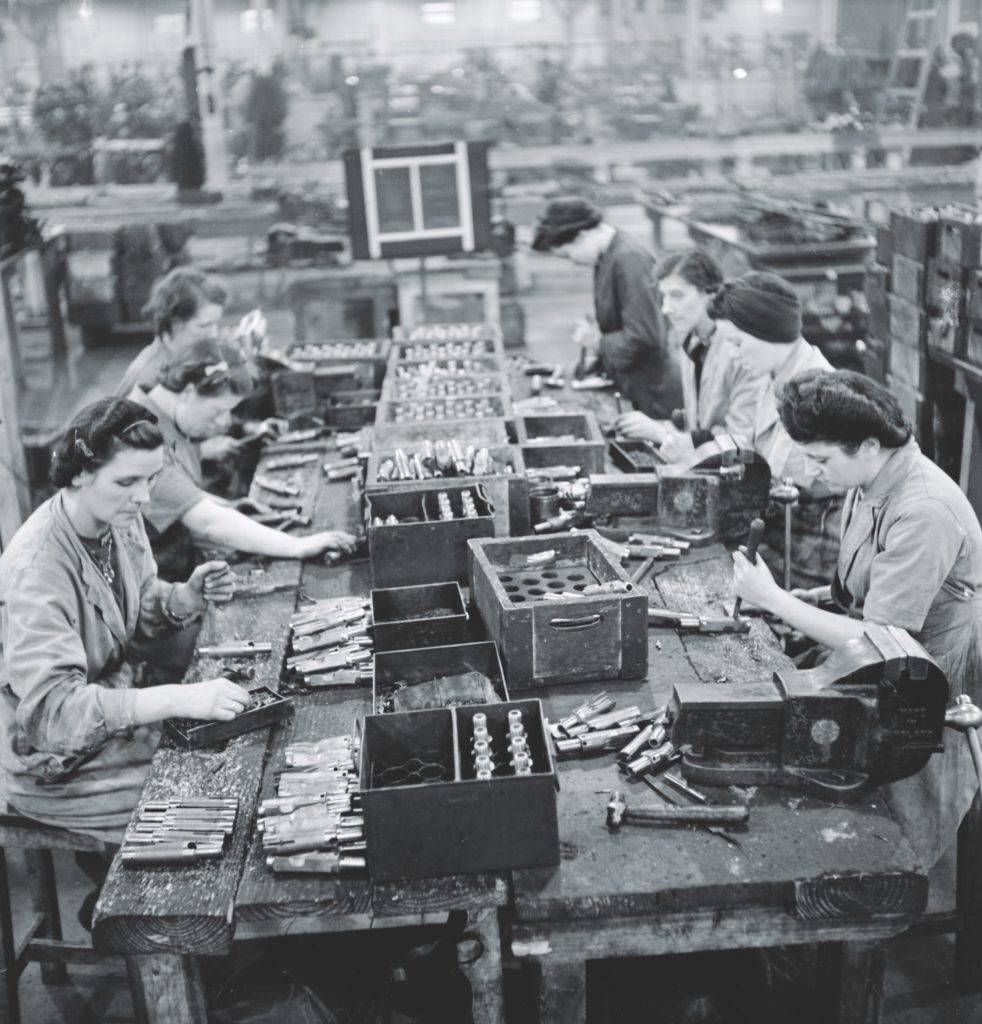

Given the shortage of precision machine tools in Britain at the time, plus the continuing stress on British manufacturing companies, the Sten was designed for stamping and pressing processes that could be performed in the humblest of workshops. Stables, lofts, even hen houses or the garrets of private homes became improvised Sten gun factories. Various Sten subassemblies were also farmed out to hundreds of small industrial operations scattered across the United Kingdom, often to companies with no experience in weapons manufacturing.

Nor was production just a British affair. The huge Small Arms Ltd. production plant in Toronto, Canada, manufactured 104,553 Mk IIs; it also made 1.1 million Sten magazines. New Zealand chipped in with another 1,000 Stens. Australia, always stubbornly independent, preferred to develop its own variation—the Owen submachine gun, which was heavier, had a wooden stock, and was rated far superior to the Mk II.

Innovations streamed in from all corners of the United Kingdom. One of the most important of them came from Walter W. Hackett, the joint managing director of Accles & Pollock, a tube-making firm in Birmingham. The War Ministry had asked Hackett how Sten barrels could be produced more efficiently. He pioneered a method in which cold hammer-forged barrels were manufactured using hardened steel mandrels, obviating the need for expensive boring and rifling machines. Hackett’s process prevented delays of up to a year in Sten production and saved 1.4 million feet of metal tubing at a time when resources were precious. Using Hackett’s method, one Sten barrel could be made every 10 seconds. Sir Claude Gibb, an engineer who oversaw British weapons manufacturing during World War II, said later that Hackett “made the greatest contribution to the production of small arms during the whole of the war”: in all, an astonishing number of Sten guns—some 4.5 million in all—were manufactured.

In the second half of 1941, soldiers began using the Sten gun in combat. Some of the early recipients had less than encouraging responses to their new weapons—first impressions not helped by its industrial crudity, especially when compared with the polished wood and high-grade steel of the long-serving Lee-Enfield rifle. “They were said to cost thirty shillings each and I do not doubt it,” one officer of the Home Guard remarked. “It is inaccurate over fifty yards and apt to be dangerous in the hands of an untrained man.” But British parachutist Alan Lee gave the Sten a qualified endorsement: “When you went into a village or went into a house, whatever it was, it was a reliable weapon. It wasn’t a reliable instrument for anything over 100 yards, but for anything close-quarters it was very reliable.”

One of the first recipients of the Mk II—and certainly the most prominent—was King George VI of Britain, who as honorary colonel in chief of the Home Guard carried his weapon around with him in a custom-built wooden briefcase. (Every night, when he and Queen Elizabeth made the 25-mile trip in a bulletproof vehicle from Buckingham Palace to Windsor Castle, the Sten gun went with them.) The king even had a shooting range installed in the gardens at Buckingham Palace and in 1940 arranged for Princess Elizabeth, age 14, and Princess Margaret, age 10, to be given shooting lessons there.

Like the British, many European resistance groups produced their own Sten guns but often, necessarily, in furtive and frequently interrupted turns in clandestine workshops. The Danish resistance made 1,000 or so Stens, adding to the 3,500 air dropped to them by the British and the 1,000 brought in by boat from Sweden. The Norwegians made about 800 Stens in basement workshops and secret rooms in Oslo. Polish resistance groups manufactured 1,300 Stens, many of them virtually handmade by local blacksmiths, machinists, and other skilled craftsmen.

The Sten became the weapon of choice of numerous resistance operations throughout Europe, from shock ambushes in narrow French lanes to heavier use in the Warsaw uprising of August–October 1944. It could be disassembled in a matter of seconds, the pieces then packed conveniently into a parachute drop box or quickly hidden behind a false wall or under floorboards. It took almost no formal training to use a Sten; once a resistance fighter learned the basic loading and unloading procedure, he had only to point it in the right direction and pull the trigger. The Sten offered the additional advantage of firing the same 9mm Parabellum bullets the Germans used, so resistance fighters could supplement their own precious supply of bullets with ammunition captured from the enemy.

For the Germans in the occupied territories, finding a Sten, or parts of a Sten, was a clear signal of organized British-supported resistance, and their retribution was swift. In 1942 the discovery of a parachute-dropped Sten hanging from a tree in Norway led Reichskommissar Josef Terboven to decree that anyone found in possession of a Sten would be summarily executed. Sometimes even less evidence brought doom. British special operations teams in France, for example, had to take utmost caution not to leave any evidence of their passing in French farmhouses, where they often made overnight stops. In one instance, German troops inspecting a haystack found a single British-made round for a Sten gun, and on the basis of that flimsy evidence killed the French family living there and burned the farm to the ground.

ONE OF THE STEN GUN’S FIRST MAJOR TESTS CAME ON AUGUST 19, 1942, when 6,000 Allied (mostly Canadian) infantry launched an exploratory amphibious operation against the German-occupied port of Dieppe, France. The operation was a fairly emphatic disaster, with some 60 percent of the attacking force killed, wounded, or captured, and the Sten proved unwieldy and inaccurate on the battlefield. Many reports from surviving Canadians spoke of Stens jamming at the worst possible moments. The problems were not entirely with the Sten’s design. The weapons had been issued immediately before the raid, and many were still clogged with packing grease when they were taken into action. Shortages of ammunition also meant that many of the Canadian soldiers had not had the chance to conduct live-fire training with the Sten before going into combat. The failures at Dieppe gave Allied planners some much-needed lessons as they began preparing for the D-Day landings, but it was not a promising early combat trial for the new gun.

Nor would the Sten’s failures at Dieppe be isolated instances. The gun was generally regarded as “unpredictable,” to use one of the more charitable terms British soldiers applied. Sometimes when an uncocked Sten was inadvertently knocked or dropped, its bolt bounced backward just enough to clear the magazine well, at which point the recoil spring would drive the bolt forward, chamber a round, and fire. This issue was particularly serious for paratroops, whose very method of deployment was an exercise in bumps and jolts. During a jump by the 1st Parachute Battalion near Tunis on November 16, 1942, four parachutists were wounded by a single runaway Sten; the 3rd Parachute Battalion suffered its only fatality when a trooper accidentally shot himself with his Sten. The failures were mainly attributable to the Sten’s magazine, whose double-stack-to-single-feed configuration was prone to jamming, a problem that was never entirely resolved. There are numerous reports of British or Commonwealth soldiers taking a bead on enemy troops, pulling the Sten’s trigger, and hearing nothing more than the bolt slapping the back of the breech with a metallic clang. Little wonder that the Sten gun earned a variety of wry nicknames.

One of the Sten’s most famous malfunctions occurred on May 27, 1942, when Jozef Gabčík, a commando in the Czechoslovak army, stepped in front of SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich’s open-topped Mercedes-Benz touring car near Bulovka Hospital in Prague. Gabčík was to fire the opening rounds in a two-man assassination attempt on the much-hated Nazi officer, one of the key architects of the Holocaust. When Gabčík pulled the trigger, nothing happened—the Sten had jammed. Gabčík’s partner, Jan Kubis, stepped into the breach, tossing a modified antitank grenade at Heydrich’s vehicle. The subsequent explosion severely wounded Heydrich, peppering his side with shrapnel and bits of upholstery that ultimately led to a case of fatal blood poisoning. The SS hunted down Gabčík and Kubis, killing them and several compatriots in a six-hour gun battle at a Prague cathedral. (They remain Czech heroes to this day.)

British airborne troops spearheading the invasion of Italy in September 1943 had their own misadventures with the balky weapon. Trooper Ron Kent of the 21st Independent Parachute Company recalled that the Sten often proved more dangerous to its users than to the enemy. Men in Kent’s company suffered several injuries because of the old model Sten’s instability. “Sid Humphries sustained a nasty nick below the knee cap,” Kent said, “when his section sergeant, rounding some rocks, accidentally caught the toe of his boot against the butt of a Sten leaning against a stone and pointing straight at where Sid was busy cooking for his section. The miserable weapon fired a nine millimeter bullet at Sid’s leg.” British parachutists and glider-borne troops carried Stens into combat during the D-Day invasion, where the bitter hand-to-hand fighting in the hedgerows and small-town streets of Normandy was precisely the sort of close-in action for which the Sten was designed.

British sergeant major Stanley Hollis, who landed at Gold Beach on D-Day, rushed to suppress a German battery at Mont Fleury. His company commander pointed out an enemy pillbox. “It was very well camouflaged,” Hollis said, “and I saw these guns moving around in the slits and I got my Sten gun and I rushed at it, spraying it hosepipe fashion. They fired back at me and they missed. I don’t know whether they were more panic-stricken than me, but they must have been.” Hollis went around to the rear of the pillbox, where he found two soldiers dead and several who “were quite willing to forget all about the war.” For his gallantry in silencing the Mont Fleury battery, Hollis received a Victoria Cross, the only one awarded for a D-Day exploit.

During the subsequent Normandy campaign British paratroops carried Stens along with rifles. The Stens went to platoon commanders and their batmen, as well as signalers, pioneers, and other auxiliary troops. In the fighting to seize and hold the vital Orne River bridge and canal bridges, Lieutenant Richard “Sandy” Smith of No. 14 Platoon, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, was leading his men across the bridge when a German threw a grenade at him. “I was very lucky,” Smith recalled. “I don’t really know what happened. I just felt this smack. I didn’t see him throw the stick grenade. I saw him climbing over the wall to get to the other side and I shot him as he was going over—I made certain too. I gave him quite a lot of rounds, firing from the hip—it was very close range.” Smith received the Military Cross for his role in the mission.

Private John Butler of the 7th Parachute Battalion was not impressed with the Sten’s lack of stopping power. “I was kneeling back looking at the top of the slope with my Sten gun pointing,” Butler later recalled. “Suddenly, a Jerry came in view with his rifle pointing towards me and I pressed the trigger of my Sten, but to my horror the man didn’t fall down as I expected and just stood there looking at me, and I was in absolute terror. Then the magazine ran out, it had been about half full, twelve to fourteen rounds, and probably took about two to two and a half seconds to fire off. And then the man came at me, collapsing on top of me and his bayonet pierced my left thigh, hit the bone and flipped out again, and the left side of my smock was covered in blood.” To Butler’s relief, he quickly saw that the German was dead—“the thud of the bullets in his chest had held him for those few seconds, though at the time I did not realize this.”

The men in the British 1st Airborne Division received new Mk V Stens before the ill-starred Market Garden operation at Arnhem, in the Netherlands, in September 1944. Though the operation was an unmitigated catastrophe for the Allies, the Mk V performed better than the Mk II. Lieutenant Jimmy Cleminson of No. 5 Platoon, B Company, 3rd Parachute Battalion, encountered a German armored vehicle on the first day of the operation. “I got up into a house and found myself behind the German vehicle,” he later recalled. “I was joined by [Major] Peter Waddy. I shot a German soldier in the garden below me with my Sten and wondered what I could do to get rid of our armored visitor.” Cleminson was wounded and captured and was later awarded the Military Cross for his service at Arnhem.

Major Erick Mackay of the 1st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, took shelter in a two-story schoolhouse close to the bridge at Arnhem, only to discover that the building was surrounded by 60 German soldiers unaware the British troops were hiding only yards away. “On a signal, [grenades] were dropped on the heads below, followed instantly by bursts from all our six Brens and fourteen Stens,” Mackay later recalled. “Disdaining cover, the boys stood up on the window-sills, firing from the hip. The night dissolved into a hideous din as the heavy crash of the Brens mixed with the high-pitched rattle of the Stens, the cries of wounded men, and the sharp explosions of grenades.”

When the Sten worked, which it did more often than not, it could be a fearsome weapon. Lance Corporal Dennis Longmate of the 4th Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment, recalled using his Sten following a brutal combat crossing of the Rhine in late 1944: “We were debating what we were going to do when a German patrol appeared, about a dozen men coming in our direction. ‘Are we going to kill or be killed? It’s them or us.’ It was pretty poor odds with a dozen of them and three of us. But I told the other two to hold their fire and when the patrol came in range I fired the Sten. I’d never killed at such close quarters before, literally seeing the whites of the eyes. I saw the bullets hit, saw them go down, all of them.”

Such accounts demonstrate that the Sten was every bit as lethal as the German MP 40, and it largely corrected the imbalance between German and British forces in the struggle of fire superiority under 100 yards. The reported problems with the Sten also must be weighed against the vast scale of its production and distribution. Hundreds of thousands of troops took the Sten into action. Many units found that, as with most weapons, proper training and maintenance were the most significant factors in keeping the Stens functional.

DESPITE ITS DRAWBACKS, THE STEN GUN WOULD HAVE A LONG LIFE IN THE POSTWAR WORLD. British troops continued to use the Sten Mk V until the late 1950s in Cyprus, Korea, Malaya, Kenya, and Suez, before the Sterling SMG (submachine gun) replaced it. Surplus World War II Stens were a standard weapon in both pre- and post-independence Israel, providing Israeli insurgents and later the fledgling Israel Defense Forces with an SMG until the indigenous arms industry produced the Uzi. Stens also cropped up in the Vietnam War, with U.S. Special Operations Group forces using the Mk II(S) for quiet ambushes or prisoner snatches. The Irish Republican Army once raided the largest British Army barracks in Northern Ireland and made off with 50 Sten guns, among other weapons. Even today, Stens occasionally make an unwelcome appearance in terrorist or criminal hands in the Middle East or the Balkans.

In 1949 Reginald Shepherd, who had retired from the military with the rank of major, went before Britain’s Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors to seek remuneration for having invented parts of the Sten gun. (He and Turpin had been denied British patents for their work on the weapon.) Though Shepherd told members of the commission that the “en” in Sten stood for England, not Enfield, the mythology surrounding the gun’s name persists to this day.

The Sten was not a perfect gun, but it was the right gun for its time and place. For all its shortcomings, the Sten had two crowning strengths: It worked (for the most part), and it was available. Those might not sound like the most superior of virtues, but in a country that was facing a clear and present threat to its very survival, they were the most important virtues of all.

As Canadian soldier S. N. Teed apostrophized poetically: “You wicked piece of vicious tin! / Call you a gun? Don’t make me grin. / You’re just a bloated piece of pipe. / You couldn’t hit a hunk of tripe. / But when you’re with me in the night, / I’ll tell you, pal, you’re just alright!” MHQ

Chris McNab is a military historian based in the United Kingdom. His most recent book is The Samurai Warrior Operations Manual (Haynes Publishing, 2019).

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2019 issue (Vol. 32, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Cheap Shot

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!