He was called America’s Ace of Aces during World War I, the highest scorer of American aerial victories over the Germans. He could just as easily have been labeled the “luckiest man alive,” however, since he survived–by his own count–135 brushes with death during his exciting lifetime.

Edward Vernon Rickenbacker was born in Columbus, Ohio, on October 8, 1890. The son of Swiss immigrants, he was the third of eight children. His parents christened him Edward Rickenbacher, but he later added Vernon as a middle name “because it sounded classy” and changed the spelling of his last name to Rickenbacker so it would be less Germanic. He answered mostly to “Rick” but would be best known during later years as “Captain Eddie.” His father was a day laborer, and life was not easy for a lad who spoke with an accent that reflected his parents’ household language.

Young Rickenbacker was admittedly a bad boy who smoked at age 5 and headed a group of mischievous youngsters known as the Horsehead Gang, but he was imbued with family values by frequent applications of a switch to his posterior by his strict father. One of his father’s axioms that he followed all his life was never to procrastinate.

At age 8, he had his first brush with death when he led his gang down a slide in a steel cart into a deep gravel pit. The cart flipped over on him and laid his leg open to the bone. He quit school at 12 when his father died in a construction accident, and he became the major family breadwinner for his mother and four younger siblings. He said in his memoirs, “That day I turned from a harum-scarum youngster into a young man serious beyond my age.” He sold newspapers, peddled eggs and goat’s milk, then worked in a glassmaking factory. Seeking more income, he worked successively in a foundry, a brewery, a shoe factory and a monument works, where he carved and polished his father’s tombstone.

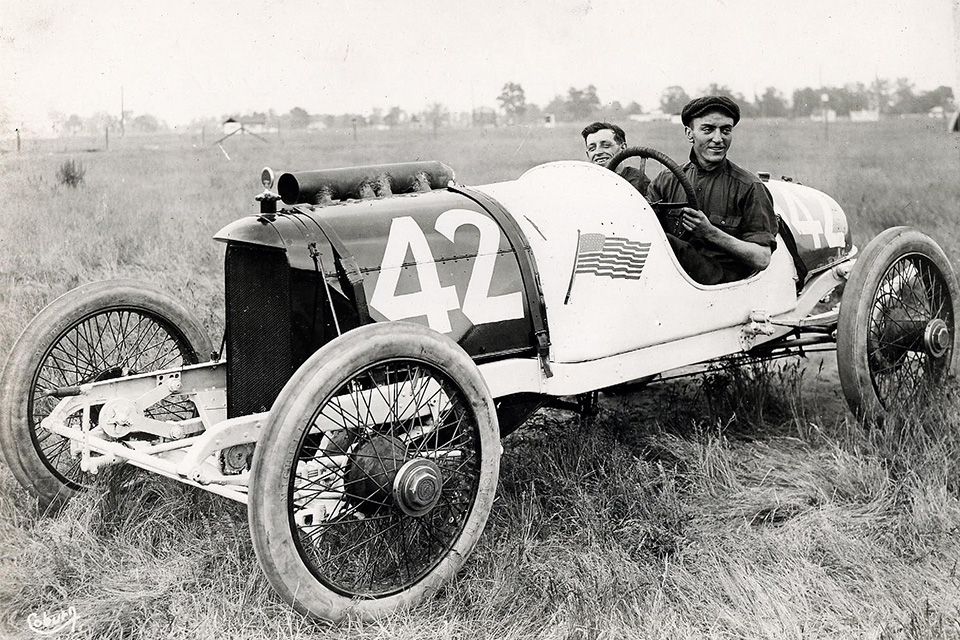

Engines became young Rickenbacker’s passion, and he found a job that changed his life in 1906 when he went to work for Lee Frayer, a race car driver and head of the Frayer-Miller Automobile Co. Frayer liked the scrawny, scrappy lad and let him ride in major races as his mechanic.

Rick later went to work as a salesman for the Columbus Buggy Co., which was then making Firestone-Columbus automobiles. He joined automobile designer Fred Duesenberg in 1912 and struck out on his own as a race car driver. He soon established a reputation as a daring driver and won some races–but not without numerous accidents and narrow escapes. After each crash he telegraphed his mother, telling her not to worry.

Although Rickenbacker set a world speed record of 134 mph at Daytona in 1914, he was never able to win the big prize at Indianapolis. While preparing for the Vanderbilt Cup Race in California in November 1916, he had his first ride in an aircraft–flown by Glenn Martin, who was beginning his own career as a pilot and aircraft manufacturer. Rickenbacker had a lifelong fear of heights, but he had not been apprehensive during the flight.

When America entered the war in 1917, Rickenbacker volunteered despite the fact that he was making a reported $40,000 a year at the time. He wanted to learn to fly, but at 27 he was overage for flight training and had no college degree. However, because of his fame as a race car driver, he was sworn in as a sergeant and sailed for Europe as a chauffeur. Contrary to legend, he was not assigned to General John J. Pershing but did wangle an assignment driving Colonel William “Billy” Mitchell’s flashy twin-six Packard. He pestered Mitchell until he was permitted to apply for flight training, claiming to be 25, the age limit for pilot trainees.

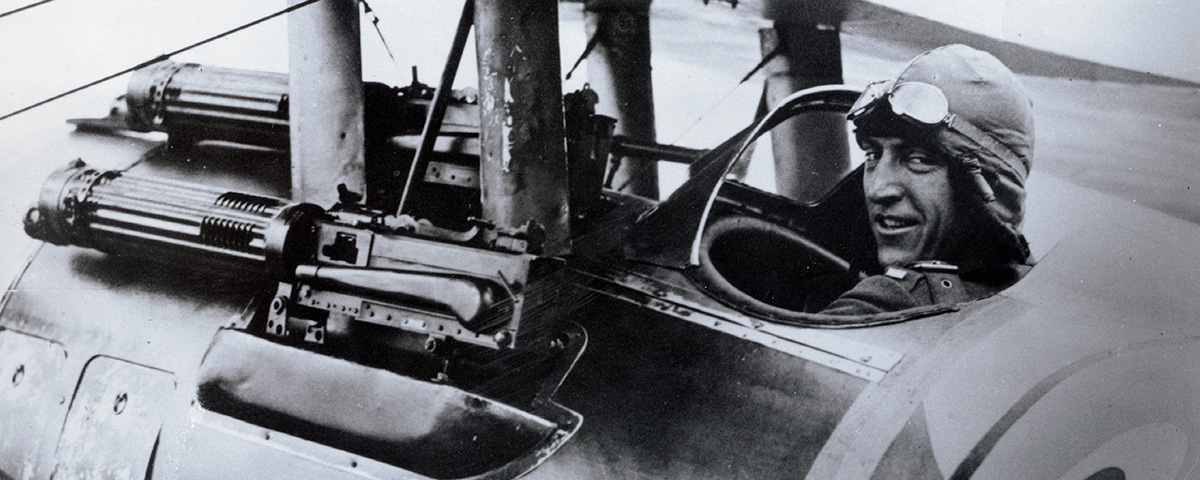

After only 17 days as a student pilot, Rick graduated, was commissioned a lieutenant and assigned to the 94th Aero Squadron, under Major John Huffer, based at Gengoult Aerodome near Toul, France. Equipped with Nieuport 28s, it was the first American-trained fighter squadron to draw blood, when 1st Lt. Douglas Campbell and 2nd Lt. Alan Winslow brought down a Pfalz D.IIIa and an Albatros D.Va on April 14, 1918.

Rickenbacker was not accepted by the other squadron members–mostly Ivy League college graduates–at first. They considered him a country bumpkin without any social graces. In fact, he was described by one Yale graduate as “a lemon on an orange tree” who tended “to throw his weight around the wrong way.”

Rickenbacker was happier tinkering with engines than socializing. Older than all the others, he was conservative in his flying and had to work to overcome a dislike for aerobatics. When he first arrived at the squadron he was coached by Major Raoul Lufbery, the training officer, but he soon developed his own aerial fighting techniques. He shared credit with Captain James Norman Hall for his first victory on April 29, 1918. He scored his first solo conquest on May 7, but it was not confirmed until after the war, when Hall–who had been shot down and taken prisoner in the same fight–reported the death of Lieutenant Wilhelm Scheerer of his captors’ unit, Royal Wurtemburg Jagdstaffel (Fighter Squadron) 64. As Rickenbacker’s string of victories grew, so did the respect of his squadron mates.

Rickenbacker’s technique was to approach his intended victims carefully, closer than others dared, before firing his guns. He had several hair-raising experiences when his guns unexpectedly jammed. He barely managed to nurse his Nieuport in for a safe landing on May 17, when the cloth ripped off its upper wing. But his luck held, and when he became an ace, his exploits–some wildly exaggerated by reporters–made headlines in the States. During interviews, he admitted he experienced fear during his encounters with the Germans but “only after it was all over.”

Rickenbacker scored his sixth victory on May 30, but on July 10 he began to suffer from sharp pains in his right ear. In Paris, the problem was diagnosed as a severe abscess, which had to be lanced and treated. He returned to the 94th on July 31 and got back into his stride on September 14, when he downed a Fokker D.VII.

On September 25, Rickenbacker was given command of the 94th, and on that same day he volunteered for a solo patrol. He spotted a flight of five Fokkers and two Halberstadt CL.IIs near Billy, France, and dived into them. Firing as he went through the formation, he shot one of each type down. His aggressive actions that day earned him the French Croix de Guerre and the coveted U.S. Medal of Honor, though the latter was not awarded until 12 years later.

By October 1, Rickenbacker’s score stood at 12 and he had been promoted to the rank of captain. He was the most successful U.S. Air Service fighter pilot alive, and the press dubbed him “America’s Ace of Aces.” He disliked that title, however, because he felt “the honor carried the curse of death.” Three others had held that title before him–Lufbery, David Putnam and Frank Luke–and all had died.

Rickenbacker was flying with greater confidence since the 94th had replaced its Nieuport 28s with more rugged Spad 13s in mid-July 1918. He had several close calls and crash landings. He barely made it back from one battle with a fuselage full of bullet holes, half a propeller and a scorched streak on his helmet where an enemy bullet had nearly found its mark.

During October 1918, Rickenbacker scored 14 victories for what he and World War I historians have always claimed made a total of 26. In the 1960s the U.S. Air Force fractionalized his shared victories, reducing his total to 24.33, including four balloons. He flew a total of 300 combat hours, more than any other American pilot, and survived 134 aerial encounters with the enemy. “So many close calls renewed my thankfulness to the Power above, which had seen fit to preserve me,” he wrote in his memoirs.

The kid from Columbus came home a national hero, but he had been humbled by the experience, unlike some who gloried in the brief fame they had won. He had no illusions about the durability of being a national hero, saying, “I knew it would be easy to go from hero to zero.” Although he was wined and dined from coast to coast and received many offers to endorse commercial products, he refused them all. When a motion picture producer offered him $100,000 to act in unspecified roles, he declined, although he was by then broke from supporting his family.

When Rickenbacker left active duty, he was promoted to major. But he said, “I felt that my rank of captain was earned and deserved,” and he used that title proudly the rest of his life.

Although he wanted to get into some aspect of aviation, he found that the industry was not really ready for him. He believed in its future and made speeches forecasting its unlimited potential. His second career choice was automobile manufacturing. With three well-known automobile executives from the EMF Company–Barney Everitt, William Metzger and Walter E. Flanders–as backers, Rickenbacker became vice president and director of sales for the Rickenbacker Motor Company. The initial Rickenbacker designs, the first cars to have four-wheel brakes, rolled off the assembly line in Detroit in 1922.

He traveled around the country in a German Junkers, attempting to set up nationwide dealerships. However, a recession in 1925 and vicious competition led to the company’s downfall. Rickenbacker resigned, thinking that might help the company, but it went bankrupt two years later. Now 35, Rickenbacker found himself a quarter of a million dollars in debt but refused to declare personal bankruptcy. He vowed to pay off every penny of debt–and did eventually, “through hard work and some fortunate business deals.”

In November 1927 Rickenbacker was offered financing by a friend to buy the majority of the common stock of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He served as the speedway’s president until after World War II, a job that was not time-consuming and allowed him to look for other means of income to repay his debts. He started a comic strip called Ace Drummond that ran in 135 newspapers and published a book titled Fighting the Flying Circus, both based on his World War I experiences.

All this was not enough activity or income for the hyperactive Rickenbacker, however, and he was also appointed head of sales by General Motors for La Salle and Cadillac autos. Meanwhile, he continued to give speeches promoting aviation and was involved in several crashes as a passenger during his flights around the country, miraculously escaping each time without injury. On one occasion the plane he was in hit a house, and the end of a two-by-four missed his head by two inches.

Rickenbacker was still so well-known that he always attracted crowds as a speaker. He is credited with helping to persuade the city fathers of 25 cities to develop airports, including one in the nation’s capital.

In 1926 he got his first experience in commercial aviation when he and several associates formed Florida Airways. When that venture folded, Rickenbacker was appointed vice president of General Aviation Corporation (formerly Fokker), followed in 1933 by vice president of North American Aviation and general manager of its subsidiary, Eastern Air Transport.

Rickenbacker made national headlines again when President Franklin D. Roosevelt canceled the commercial airlines’ air mail contracts in February 1934 and announced that the Army Air Corps would take over those routes. To show that the airlines were better qualified to fly the mail, Rickenbacker–with Jack Frye, vice president of TWA, and a contingent of journalists–flew coast-to-coast in the one and only Douglas DC-1, granddaddy of all “Gooney Birds,” in 13 hours and two minutes, a transcontinental record for commercial planes. It was a public protest against what Rickenbacker bitterly denounced as “legalized murder,” since three Army pilots had died trying to get to their assigned stations.

The Air Mail Act of 1934 was passed after several more Army pilots were killed because they were untrained in instrument flying and their aircraft were inadequately equipped. The legislation changed the structure of U.S. civil aviation, establishing the Civil Aviation Authority, which was granted control over airports, air navigation aids, air mail and radio communications. Under the terms of the act, General Motors had to divest itself of most of its aviation holdings, but it was permitted to retain General Aviation Corporation and a reorganized Eastern Air Transport, with its name changed to Eastern Air Lines.

When Rickenbacker was named Eastern’s general manager, he wanted to make the airline independent of government subsidy. He began to build the airline by improving salaries, working conditions, maintenance and passenger service, and making stock options available to employees. A modest profit ($38,000) in 1935 proved the worth of the changes he had instituted. Ten new 14-passenger DC-2s, the beginning of “The Great Silver Fleet,” were ordered to replace Stinsons, Condors, Curtiss Kingbirds and Pitcairn Mailwings. Rickenbacker co-piloted the first DC-2, Florida Flyer, on a record-setting flight from Los Angeles to Miami on November 8, 1934.

Eastern at the end of 1934 was setting the pace for air transportation by flying passengers, mail and express on eight-hour nighttime schedules between New York and Miami and nine-hour schedules between Chicago and Miami to make connections with Pan American’s system to South America and the Caribbean. In April 1938, Rickenbacker and several associates bought the airline for $3.5 million and he became its president and general manager. He promptly sat down and wrote a paper titled “My Constitution,” which outlined 12 personal and business principles that would guide him in leading the airline. One of them was indicative of his work ethic: “I will always keep in mind that I am in the greatest business in the world, as well as working for the greatest company in the world, and I can serve humanity more completely in my line of endeavor than in any other.”

A weather reporting and analysis system was inaugurated, and radio communications were improved. A reduction in fares brought an immediate increase in passenger traffic. The company became a bonded carrier, the first airline in the world to take such an action. It meant that goods entering the U.S. by air or surface craft could be transported by Eastern under bond for delivery to any city having a custom house. As Rickenbacker saw it, Eastern was the first airline to operate as a free-enterprise company–without government subsidy; for many years, it was the only one. In 1937, it was also the first airline to receive an award from the National Safety Council, after having operated for seven consecutive years (19301936) and flying more than 141 million passenger miles without a passenger fatality. However, that record ended in August 1937 with a fatal DC-2 crash at Daytona Beach.

On February 26, 1941, Rickenbacker’s personal luck nearly ran out. He was aboard a DC-3 equipped as a sleeper that smashed into trees on an approach to Atlanta; 11 passengers and the two pilots died. For days Rickenbacker, badly injured, hovered between life and death, and it took nearly a year before he could get back to work. Some said that it was only Rickenbacker’s cantankerous nature that pulled him through a difficult recovery. Afterward he slumped a little and walked with a slight limp.

In the journey from fighter ace to airline president, Rickenbacker’s personality turned away some would-be admirers who found it hard to accept his brusqueness and caustic way of “chewing out” subordinates–in private or before several hundred people. Rickenbacker could never get used to the idea of women working for an airline, especially as stewardesses. He preferred to hire male stewards because he believed they were less likely to leave the company soon after being trained. He worked a seven-day week himself, demanded that his employees work on Saturdays, and was a fanatic about punctuality and a penny-pincher when it came to company expenses. (He had to personally approve any expenditure over $50.)

But many of his associates thought his toughness was a sham and tried not to take his scathing comments too much to heart. He was always able to make instant, no-nonsense decisions, and he was fair and loyal to his employees, despite his acidic manner. Most important, he got results. He set his own annual salary at $50,000 in 1938, and it never changed over the next 25 years–despite the fact that he built the airline into one of the nation’s four largest carriers during that time.

Rickenbacker continually expounded on the old-fashioned values, especially thrift. (He always put out the lights in unoccupied offices he found in his frequent prowlings around the airline’s headquarters.) He started a company newspaper–Great Silver Fleet News–which carried his personal advice about living and working. One issue had this wise counsel under the heading, “Captain Eddie Says”: “If you cannot afford it, do without it. If you cannot pay cash for it, wait until you can; but do not in any circumstances permit yourself to mortgage your future and that of your family through time payment plans or other devices.” Subsequent editions sermonized: “You cannot bring about prosperity by discouraging thrift,” and “None of us here is doing so much work that he cannot do more.”

By the end of 1941, Eastern was serving 40 cities with 40 DC-3s. There were also three Stinson Reliants used for instrument training and a Kellett autogiro that flew the mail on an experimental basis from Philadelphia’s main post office to the Camden, N.J., airport.

The advent of World War II drastically changed all the commercial airlines. Eastern had to give up half its fleet to the military services and took on the task of military cargo airlift, flying Curtiss C-46s to South America and across the South Atlantic to Africa. With the government dictating what the airlines did, Rickenbacker was only able to stand by and see that Eastern held up its end.

In September 1942 Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson asked Rickenbacker to visit England as a non-military observer, to evaluate equipment and personnel because of his “clear and sympathetic understanding of human problems in military aviation.” Rick asked for a salary of only a dollar a year and paid his own expenses. He was offered a commission as a brigadier general but refused it. The offer was upped to major general and again he refused. He wanted to be able to criticize whatever he found wrong without restraint.

When Rickenbacker returned to the States that October, Stimson immediately sent him to the Pacific on a similar inspection mission, which included taking a memorized, verbal message to General Douglas MacArthur from President Roosevelt. He was en route in a Boeing B-17 from Honolulu to Canton Island when the pilot got lost and had to ditch after running out of fuel. One of the eight men aboard was seriously injured during the ditching. The men retrieved three rafts, some survival rations and fishing kits from the sinking bomber, then roped rafts together to provide a larger target for search planes.

The next 22 days became a classic survival saga. Rickenbacker, dressed in his trademark gray fedora hat and business suit, took command of the situation, although a civilian. Such a strong-willed, independent thinker would not let military rank prevent him from stating what he thought and what decisions should be made.

No one knew where to look for them when they were overdue at Canton Island. They nearly starved and had only a few oranges for liquid until they caught some rainwater during squalls. Rickenbacker took charge of doling out the oranges and water in equal shares each day. Rickenbacker’s felt hat was used to catch the water, which was wrung out into a bucket from soaked articles of clothing.

The salt water quickly corroded the weapons that several had carried from the plane, so they would not fire when a few birds appeared overhead. Fish lines netted a shark, which tasted so bad no one could keep it down. But they also managed to catch smaller fish, which they divided into equal portions. Sharks were their constant companions, continually scraping against the bottom of the rafts. Sunburn was another serious threat.

As the days dragged monotonously on and no search planes appeared, Rickenbacker cajoled, insulted and angered everyone in an attempt to keep their hopes alive. One man tried to commit suicide to make room for the others, but Rickenbacker, accusing him of being a coward, hauled him back in. When all seemed hopeless, a sea swallow (similar to a sea gull) landed on Rick’s hat and he caught it. He twisted its neck, de-feathered it and cut the body into equal shares; the intestines were used for bait. As far as Rickenbacker was concerned, the incident was proof that they would soon be rescued and should not lose faith. He was convinced that God had a purpose in keeping them alive and insisted that prayers be said each night.

One man did die, however, and his body was allowed to float away from the raft as the others recited the Lord’s Prayer. They all steadily weakened as time went on, and bitter arguments ensued with Rickenbacker as the focus of harsh remarks. But the airline executive believed that he must not admit defeat, and he used sarcasm and ridicule to keep the others from giving up. He later learned that several of the other survivors had sworn an oath that they would continue living just for the pleasure of burying him at sea.

After the second week afloat, there were several frustrating days when search planes flew nearby but failed to see them. It was decided after some wrangling that the three rafts would be allowed to drift apart–in the hope that at least one might be seen. After three weeks, a search plane saw one of the rafts and the men were promptly picked up; another raft drifted to an uninhabited island, where the occupants were found by a missionary who had a radio. Rickenbacker’s raft was located by a Navy Catalina flying boat, and once more Captain Eddie became front-page news. He had lost 60 pounds, had a bad sunburn and salt water ulcers, and was barely alive, but the famous Rickenbacker luck had held. The Boston Globe captioned his picture as “The Great Indestructible.”

Although he was weakened by the ordeal and could have come home immediately to a hero’s welcome, Rickenbacker continued on his mission to see General MacArthur and visit some bases in the war zone. Upon his return, he briefed Secretary Stimson and made extensive recommendations about survival equipment that should be adopted on a priority basis. Among them was a rubber sheet to protect raft occupants from the sun, as well as catch water. Another was the development of small seawater distilling kits. Both items eventually became standard equipment aboard lifeboats and aircraft life rafts.

Rickenbacker continued to serve the war effort by speaking at bond rallies and touring defense plants, and in mid-1943 was sent on a three-month, 55,000-mile trip to Russia and China via American war bases in Africa “and any other areas he may deem necessary for such purposes as he will explain in person.” The mission included checking what the Russians were doing with American equipment under the Lend-Lease agreement. He was allowed a rare view of Russian ground and air equipment and returned with valuable intelligence information.

Meanwhile, a wave of affection for Captain Eddie had led to his being touted by some as a candidate for president against Roosevelt, with whom he had strongly disagreed on many occasions. He was honored, he said, but “I couldn’t possibly win. I’m too controversial.”

When it appeared that victory in World War II was on the horizon in late 1944, the airlines began to return to normal operations. Rickenbacker encouraged Eastern’s expansion and placed orders for Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-4s. Those were followed by Martin 404s and Lockheed Electras. The Cold War began with the Berlin Airlift, followed by the Korean War, which forced more changes upon the airlines.

The introduction of jets to airline operations in the late 1950s caused serious adjustment problems. Rickenbacker resisted the changeover to some extent. He later recalled, “To keep up with the Joneses, we had to replace perfectly good piston-powered and turboprop airliners with the expensive new jets.” He preferred that the other airlines be first to take the risk of breaking them in.

Rickenbacker did not like the way the government interfered with private enterprise and believed it leaned toward more and more bureaucracy and control. He battled the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) about routes and fares and resisted what the competition was making him adopt against his better judgment. For example, he thought the other airlines were wrong in serving hot meals and labeling them “free.” Since the CAB was subsidizing his competitors, he reasoned, the costs came from the taxpayers. He predicted that passengers would eventually have to pay for liquor, which they do today. And Eastern finally had to give in and hire female flight attendants.

In 1953, Rickenbacker moved up to chairman of the board but remained general manager. In his memoirs, he proudly stated that in his 25 years as head of Eastern” “We were never in red ink, we always showed a profit, we never took a nickel of the taxpayers’ money in subsidy, and we paid our stockholders reasonable dividends over the years, the first domestic airline to do so. During the postwar years, when all the other lines were in red ink and were running to the Civil Aeronautics Board for more routes and more of the taxpayers’ money in subsidies, the Board would point to Eastern Air Lines as a profitable company and suggest that the other airlines emulate our example.”

When a new Eastern president was appointed, Rickenbacker found it difficult to let go of the reins. The company began a slow downhill slide as competition got tougher and Rickenbacker refused to give up the power in the company he had held for so many years. One of the noteworthy innovations during this period, however, was the Eastern Air-Shuttle between Washington and New York. It began on April 30, 1961, with Lockheed Constellations and operated 20 round trips per day, flying empty or full, with no reservations required.

Rickenbacker reluctantly retired from Eastern on the last day of 1963 at age 73. He bought a small ranch near Hunt, Texas, but it proved to be too remote, especially for his wife, Adelaide. After five years, they donated the ranch to the Boy Scouts, lived in New York City for a while, and then moved to Coral Gables, Fla. Rickenbacker suffered a stroke in October 1972, but his famous luck held once more, and he recovered enough to visit Switzerland. He died there of pneumonia on July 23, 1973.

Captain Eddie’s eulogy was delivered in Miami by General James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle; his ashes were buried beside his mother in the Columbus, Ohio, family plot. Four jet fighters flew overhead during the ceremony. One turned on its afterburners and zoomed up and out of sight in the traditional Air Force “missing man” salute to a brother pilot.

In an obituary published in a national magazine, William F. Rickenbacker, one of Captain Eddie’s two sons, wrote: “Among his robust certainties were his faith in God, his unswerving patriotism, his acceptance of life’s hazards and pains, and his trust in persistent hard work. No scorn could match the scorn he had for men who settled for half-measures, uttered half-truths, straddled the issues, or admitted the idea of failure or defeat. If he had a motto, it must have been the phrase I’ve heard a thousand times: ‘I’ll fight like a wildcat!'”

C.V. Glines is a contributing editor and a frequent contributor to Aviation History. For additional reading, he recommends: Rickenbacker, by Edward V. Rickenbacker; Rickenbacker’s Luck: An American Life, by Finis Farr; and From the Captain to the Colonel, by Robert J. Serling.

This feature originally appeared in the January 1999 issue of Aviation History. Click here to subscribe today!