When political parties’ fight for power turns violent, the only man capable of restoring order was the defender of Little Round Top

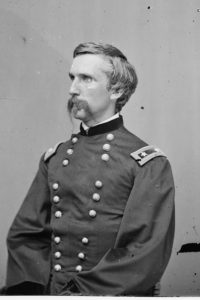

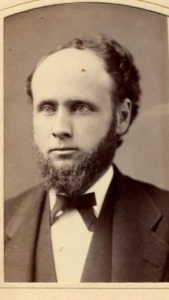

Joshua Chamberlain had been in dangerous places before. On July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Colonel Chamberlain led his 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry onto Little Round Top, successfully defending the rocky height against Confederate attackers. On June 18, 1864, Chamberlain was nearly killed outside Petersburg, Virginia, when a slug passed through his torso from hip to hip, leaving a terrible wound that tormented him for the rest of his life. Yet he returned to duty in the Army of the Potomac and fought on until Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House—a surrender that Chamberlain officially oversaw.

In January 1880, though, Chamberlain was facing a threat not from Confederate soldiers but from fellow Mainers enraged by rumors of a stolen election. As the commander of the state’s militia, Chamberlain struggled to keep electoral passions from erupting into violence, in the process enduring the wrath of people on both sides of the political divide. When an aide informed him that January 14 that a group of angry men had arrived at the state house in Augusta demanding his blood, Chamberlain made his way to the building’s front steps to confront the crowd personally.

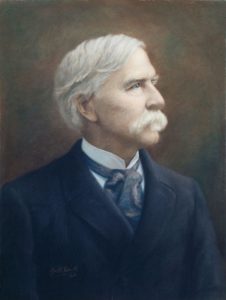

At 51, grayer than he had been almost 17 years earlier at Gettysburg, the old soldier still sported his flowing mustaches and retained his wartime air of command. “Men, you wish to kill me, I hear,” he said. “Killing is no new thing to me. I have offered myself to be killed many times, when I no more deserved it than I do now. Some of you, I think, have been with me in those days.” Chamberlain declared that he intended to follow the law and see the “rightful government” seated. He threw open his coat. “If anyone wants to kill me for it, here I am. Let him kill!”

Politics had brought Maine to this deplorable juncture. The Republican Party had dominated the state since shortly after the party’s founding in the 1850s and since 1856 had had an uninterrupted hold on the governorship, much to Democrats’ frustration. The balance of power began shifting in the latter 1870s thanks to the rise of a third party, the Greenbacks, whose adherents backed soft money over the hard money represented by gold and silver. Paper money, Greenbackers believed, was better for Maine’s agrarian economy.

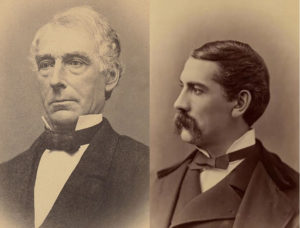

For their 1878 gubernatorial candidate, the Greenbackers selected Joseph L. Smith, a lumberman from Old Town. The Republicans renominated incumbent Governor Selden Connor, who had commanded the 7th Maine Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War and had been badly wounded during the Battle of the Wilderness. The Democrats chose Alonzo Garcelon, a former Republican from Lewiston. A Bowdoin College graduate and a doctor, Garcelon had served as Lewiston’s mayor and as Maine’s surgeon general during the Civil War.

Although Republican Connor received the most votes in the election, he did not win the majority required by law for him to be the victor in the three-candidate race. That left it to the Senate to choose between two candidates selected by the House. The House picked Smith and Garcelon. Republicans saw the Democrat as the lesser of two evils, and the Senate selected Garcelon as governor.

The governor’s term was for a single year, and in 1879 the Greenbackers again nominated Smith at a raucous convention in Portland. The Republicans met in Bangor and nominated the relatively unknown Daniel F. Davis. The Democrats, also in Bangor, nominated Garcelon for another term. The election took place on September 8 and for the second time in a row, no candidate won a majority. Davis came in first, Smith second, and Garcelon a fairly distant third. Republicans had won a majority of 29 seats in the House and 7 in the Senate. Once again, the Senate would choose the governor, but now Democrats and Greenbackers, allied as “Fusionists,” schemed to tilt the balance in their favor by “counting out” victorious Republican candidates on technicalities and awarding those seats to Fusionists. Once the Fusionists gained a majority in the Senate, they would make Smith governor.

According to Maine law, community selectmen, supervisors, or aldermen used forms provided by the state printer to record election returns. The forms were sent to Augusta for the governor and his executive council to certify. In 1879, instead of routinely certifying the tallies the executive council found creative ways to disqualify Republicans. Council members threw out votes in Republican-dominated Skowhegan because the ballot had been printed in two columns instead of the requisite one column. They discarded some results because a certifying official had written in a candidate’s initials, not his full name, or left out a “Jr.” The executive council counted out returns from two towns on grounds that one person had signed for all three selectmen, contrary to law. The selectmen in question protested that they all had signed the return as required. In the return from Gouldsboro, someone had changed the middle initial of Republican candidate Oliver P. Bragdon to a B, triggering disqualification. Later examination showed that the return obviously had been tampered with. “If there be a lower depth than this to which men can sink, it is not on God’s green earth,” said the Ellsworth American.

When the election results were announced on December 17, the council had wiped away the Republican majorities and given the Fusionists control of both houses. Anger and revulsion swept Maine. Republicans—and fair-minded members of the other parties—began attending “indignation meetings” statewide. At a meeting in Augusta, a minister preached a sermon declaring, “Mob violence would settle nothing whatever, but open, systematic war would if it must be had.” There were “bold and stirring speeches” in Bangor, where Norumbega Hall was “packed to almost suffocation” and Mayor William H. Brown denounced the counting-out as “the blackest crime ever perpetrated in the United States.” Speakers compared the situation to Fort Sumter, the Revolutionary War, the French Revolution, and the Bible’s Book of Revelation. Violence seemed imminent. “I thank God that I am not too old to carry a musket,” said one Bangor speaker.

Such talk appears to have prompted Governor Garcelon to act. On Christmas morning, strangers were reported to be busy in the state arsenal in Bangor. Mayor Brown and other men set out to investigate. They reached the arsenal to learn that two wagons loaded with arms and ammunition had just departed for the train station. The delegation caught up to the wagons at the Kenduskeag Bridge, where a mob of concerned citizens had blocked passage. The wagon master, a clerk named French from the adjutant general’s office in Augusta, said Garcelon had ordered him to bring weapons to the capital. Brown suggested that French return everything to the arsenal before the situation got out of hand. As the wagons turned around, the crowd gave a hearty three cheers and dispersed.

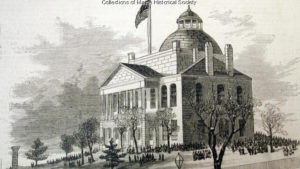

In Augusta, Mayor George E. Nash, a Civil War veteran, advised the governor that he had 200 special policemen able to deal with any trouble. Even so, Garcelon meant to get those arms from Bangor. On December 30, 120 rifles and 20,000 rounds of ammunition from the Bangor armory reached Augusta by train. A two-horse sled took them to the state house. “There were large crowds in the streets through which the teams passed, and the bells of some of the churches were tolled, but no attempt was made to interfere with the transfer,” The Kennebec Journal reported. Maine seemed on the brink of civil war.

To protect the statehouse from insurrection, Garcelon and his council recruited a paramilitary force. The arrival of these recruits, some of questionable character who had spent time in state and county prisons, gave the state house the feeling of an armed camp. “The doors are locked, the windows guarded, and the approaches watched,” reported the Boston Herald. “On trying to enter, a rifle pointed at the stranger warns him to go slow. His business stated, he proceeds through the half dozen men about the door, but at every turn, on every flight of stairs, in every room, he finds armed men.”

Republicans demanded that Garcelon ask the Maine Supreme Court to render an opinion about the electoral issue. The governor resisted. When he finally did submit questions to the court, the justices sided with the Republicans. Garcelon, due to leave office on January 7, ignored the ruling. Anarchy threatened. A rattled Garcelon turned to the one man he thought capable of steering Maine through the crisis—the hero of Little Round Top.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain had been a professor at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, when the Civil War began. In 1862 he volunteered to fight, resigned his professorship, and became lieutenant colonel of the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry. By Gettysburg he was a full colonel and regimental commander and was leading a brigade when he fell outside Petersburg in 1864. General-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant approved an immediate promotion to brigadier general for the apparently mortally wounded soldier. But Chamberlain survived and insisted on returning to the field as soon as he could. After the war he served four one-year terms as Maine’s governor before returning to Bowdoin as the college’s president. In 1874 Chamberlain faced a serious crisis at the college when students mutinied over his program of mandatory military drill. Chamberlain dismissed the rebellious students and sent a letter to their parents, saying their sons would be allowed back if they signed a letter promising to follow the college’s rules. Almost all the students did, and the college board compromised by making drill optional. The program was eliminated in 1882.

Chamberlain’s campus conflicts were small potatoes compared to the turmoil roiling Maine. The state’s politics had reached “a strange pass,” Chamberlain wrote later. “The intense greed,—not to say need,—of getting possession of the government led to practices not contemplated by the constitution, nor accordant with truth and right. Orders came, as in war times: ‘Win at all costs!’ Hence distrust was easily wakened, and charges readily framed.”

Chamberlain mostly had remained aloof from the growing fray. He was among those who urged Garcelon to consult the Supreme Court but had not attended any indignation meetings. Senator James G. Blaine, the political kingpin who chaired Maine’s Republican Party, asked Chamberlain to organize a meeting in Brunswick, but the ex-governor demurred, saying “what we now need to do is not to add to the popular excitement which is likely to result in disorder and violence, but to aid in keeping the peace by inducing our friends to speak and act as sober and law abiding citizens.” Chamberlain called resorting to bloodshed deplorable. “I cannot bear to think of our fair and orderly state plunged into the horrors of a civil war,” he said. He encouraged Blaine to “do all you can to stop the incendiary talk which proposes violent measures, and is going great harm to our people.”

Even though Chamberlain was a Republican, Garcelon summoned the well-respected old soldier to Augusta to take charge of the militia during the emergency. On January 5 the governor issued an order: “Major-General Joshua L. Chamberlain is authorized and directed to protect the public property and institutions of the State until my successor is duly qualified.”

In Augusta, Chamberlain found the capitol barricaded and Garcelon’s mercenaries patrolling. “We have no right to keep these armed ruffians here, and I will not remain if they are not sent away in half an hour,” he reportedly told the governor. Chamberlain also ordered the arms from Bangor returned and warned local militia that they should follow only his orders. He notified three nearby militia companies and an artillery battery to be ready to come to Augusta immediately if needed. As he surveyed the situation, Chamberlain determined to remain above partisan politics, a tightrope act that opened him to attacks from both sides. Republicans railed against him as “The Republican Renegade,” “The Fusionist Sympathizer,” and “the Most Dangerous Man in Maine.” Fusionists called him “The Lawless Usurper,” “The Tool of Blaine,” and “The Serpent of Brunswick.”

Republican attacks and indignation over the election results were having an effect. A Democrat from Farmington, the ironically named Louis Voter, sent a letter resigning from the seat he had received when the Fusionists had counted out his Republican opponent. Other Fusionist candidates did likewise. Despite the cracks in their front, the Fusionists moved forward with plans to form a legislature. When the party met in Augusta on January 7, citizens massed at the state house to follow the proceedings, causing a commotion and clogging hallways and stairs. Most Republican members stayed away. Despite protests by the few Republicans present, Garcelon swore in the members of the House and Senate. The Senate voted for James D. Lamson as its president and the House chose John C. Talbot as its speaker.

The Republicans convened to elect their own legislature on January 12, even though Brandon Lancaster, the Fusionist superintendent of the state house building, tried to thwart them by locking the doors and spiriting away oil for the interior lamps. The Republicans chose Joseph A. Locke as Senate president and George E. Weeks as speaker of the house and voted to submit questions about the election to the Supreme Court.

Lamson met with Chamberlain and asked to be recognized as acting governor. Chamberlain refused. He advised Lamson to refer the matter to the Supreme Court. “There are only two ways to settle the question at issue and quiet the public minds,” Chamberlain said, “by following strictly the constitution and laws or by revolution and blood.” When Republican Joseph Locke asked Chamberlain to recognize his claim to the governorship, the general refused to do that, too. He later said that both sides had dangled the possibility of a seat in the U.S. Senate were he to support their claims.

Chamberlain heard rumors that he was going to be arrested for treason, or that he would be kidnapped by the Fusionists. Mayor Nash assigned policemen to escort the general in Augusta, and Chamberlain had his son fetch two of his pistols from Brunswick. Hearing the kidnap rumor, Chamberlain surreptitiously changed his lodgings at night.

Republicans were not happy with him, either. Thomas Hyde, a friend and fellow Civil War veteran, arrived in Augusta to warn Chamberlain that Republicans were willing to use force and “pitch the Fusionists out of the window.” “Tom, you are as dear to me as my own son,” Chamberlain replied. “But I will permit you to do nothing of the kind. I am going to preserve the peace. I want you and Mr. Blaine and the others to keep away from this building.” To his wife, Chamberlain wrote, “I wish Mr. Blaine & others would have more confidence in my military ability.” Too many people, he said, were worried about “their precious pink skins.”

For Chamberlain, January 14, 1880, was “another Round Top,” a day when Maine’s fate swayed in the balance. “There were threats all morning of overpowering the police & throwing me out the window, & the ugly looking crowd seemed like men who could be brought to do it (or to try it),” he later told his wife. Some 30 angry men, joined by more, appeared at the state house, apparently ready to fight, when Chamberlain threw open his coat and dared them to strike. A fellow veteran pushed through the crowd. “By God, old General, the first man that dares to land a hand on you, I’ll kill him on the spot,” he shouted. The intruders crept away in shame.

“A storm is raging around me here in the State House; & I have no doubt of the designs of wicked men inside this building as well as outside,” Chamberlain wrote to Blaine on January 16. Still, he continued to resist Republican demands to call out the militia, believing the gesture would lead to bloodshed. “Whoever first says ‘take arms!’ has a fearful responsibility on him, & I don’t mean it shall me be who does that.”

On January 16, the Fusionist legislature elected Joseph L. Smith governor. Smith tried to oust Chamberlain, who stood firm even when threatened with arrest. The next day the Supreme Court, ruling on questions submitted by the Republicans, declared unanimously that Garcelon and his council lacked standing to judge the qualifications of the members of the legislature. Triumphant, the Republicans convened their legislature and elected Daniel F. Davis governor. As Davis arrived at the state house to take the oath of office, “the audience rose up as one man, and the sound that followed was like the roar of the sea, steadily increasing in volume, until the old Capitol building fairly rocked.” When Davis tried to enter the governor’s office, he discovered that Fusionists had locked the door and taken the keys. Davis had someone pick the lock.

The next day’s Kennebec Journal headline read, “HALLELUJAH! The Victory won!”

Chamberlain considered his duty done and returned to Brunswick.

However, the Fusionists had not given up. On January 19 a Fusionist contingent pressed to enter the capitol. Denied admittance, the partisans withdrew to discuss taking the capitol by force. Governor Davis summoned militia units from Auburn and Richmond and had a Gatling gun emplaced on the statehouse grounds. The Fusionists met for the last time on January 28 and adjourned their legislature until August. It never met again. Instead, legitimately elected Fusionist candidates joined the legally recognized legislature. The crisis was over.

In February the state appointed a committee of seven representatives and three senators to investigate the disputed election and its aftermath. Garcelon testified that he had known nothing of returns being altered. He professed remarkable ignorance about the political makeup of Maine towns and various candidates’ party affiliations. “So far as that matter is concerned. I presume there is not a man in the State who knows so little about the political complexion of towns or members of the Legislature as I do,” he told his examiners. “It is a matter I never inquired into.” No one was prosecuted for the apparent vote tampering, perhaps to avoid reigniting the passions that had almost plunged the state into armed conflict.

Ironically, Chamberlain’s handling of the crisis probably ended his political ambitions. On January 12, at the height of the uproar, he had sent a letter to John Appleton, the state supreme court’s chief justice, declaring that the Fusionist Lamson “entitled to be recognized.” Chamberlain later explained that he meant that Lamson should have been allowed to present questions to the Supreme Court, not that he should be recognized as governor. When word of the letter got out, though, Republicans accused Chamberlain of betraying the party. Chamberlain had hoped to become a U.S. senator one day, but the rumpus over the letter, which Chamberlain biographer John Pullen said “was perhaps too hastily written,” doomed his chances.

Despite the blow to his political hopes, Chamberlain remained pleased with the way he had steered Maine away from the precipice. Looking back years later on the tumult, he said it was “by far the most important public service he ever rendered.”

Tom Huntington is a former editor of American History and the author of several books, including Maine Roads to Gettysburg and Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg. This article is adapted from Maine at 200: An Anecdotal History Celebrating Two Centuries of Statehood by Tom Huntington (Down East Books, 2020).

*This is a web-exclusive story by American History. For more stories in print, subscribe to our magazine.