If it’s springtime in the United States in an even-numbered calendar year, then it must be the dawn of another supposedly do-or-die election season—another of those contests, as we the people have been warned from time immemorial, that will bring either the joyous revival or the devastating ruination of the country we all love…with salvation possible if only we vote the right way.

Let the fight for the U.S. House and Senate begin, and let the inevitable, accompanying doomsday warnings commence as well. But to every talking head who proclaims the 2014 contest the most important in American history, and to every viewer who believes him, know this: 150 years ago, in the midst of the most devastating war that ever roiled the continent, battle-weary Americans, men in uniform included, went to the polls to choose a president. Had the outcome been different, our country might never have been the same: Slavery might have been revived and sustained, the preservation of the Union abandoned and the nation itself permanently split in two—and by now, conceivably, reduced to an array of weak and Balkanized ministates.

The historian Amanda Foreman was once asked—half-jokingly—what accent Americans might be speaking with today had the South won. She didn’t hesitate with her answer: German. Abraham Lincoln’s defeat in 1864 might have ushered in an era of debilitating vulnerability that would have made the hemisphere easy pickings for the aggressors of World War II.

In fact, Lincoln came astonishingly close to losing in 1864, and that he did not remains something of a political miracle. For one thing, no president had won a second term since Andrew Jackson. With tradition encouraging one-term-only chief executives, Lincoln’s own Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase plotted openly, and rather clumsily, to replace him on the 1864 Republican ticket. When the Chase boom faded, former General John C. Frémont, the losing candidate to James Buchanan in the 1856 contest, agreed to run on a third-party ticket. Anxious Republicans searched for other alternatives to Lincoln, determined to maintain their hold on both the White House and federal patronage. For a time, leaders and journalists flirted openly with General Ulysses S. Grant, even though he admitted that while he had not voted in the presidential election four years earlier, he would have voted against Lincoln and the Republicans had he exercised his franchise. But Grant also made it clear he would not be a candidate in 1864: The loyal general would never challenge his own commander-in-chief.

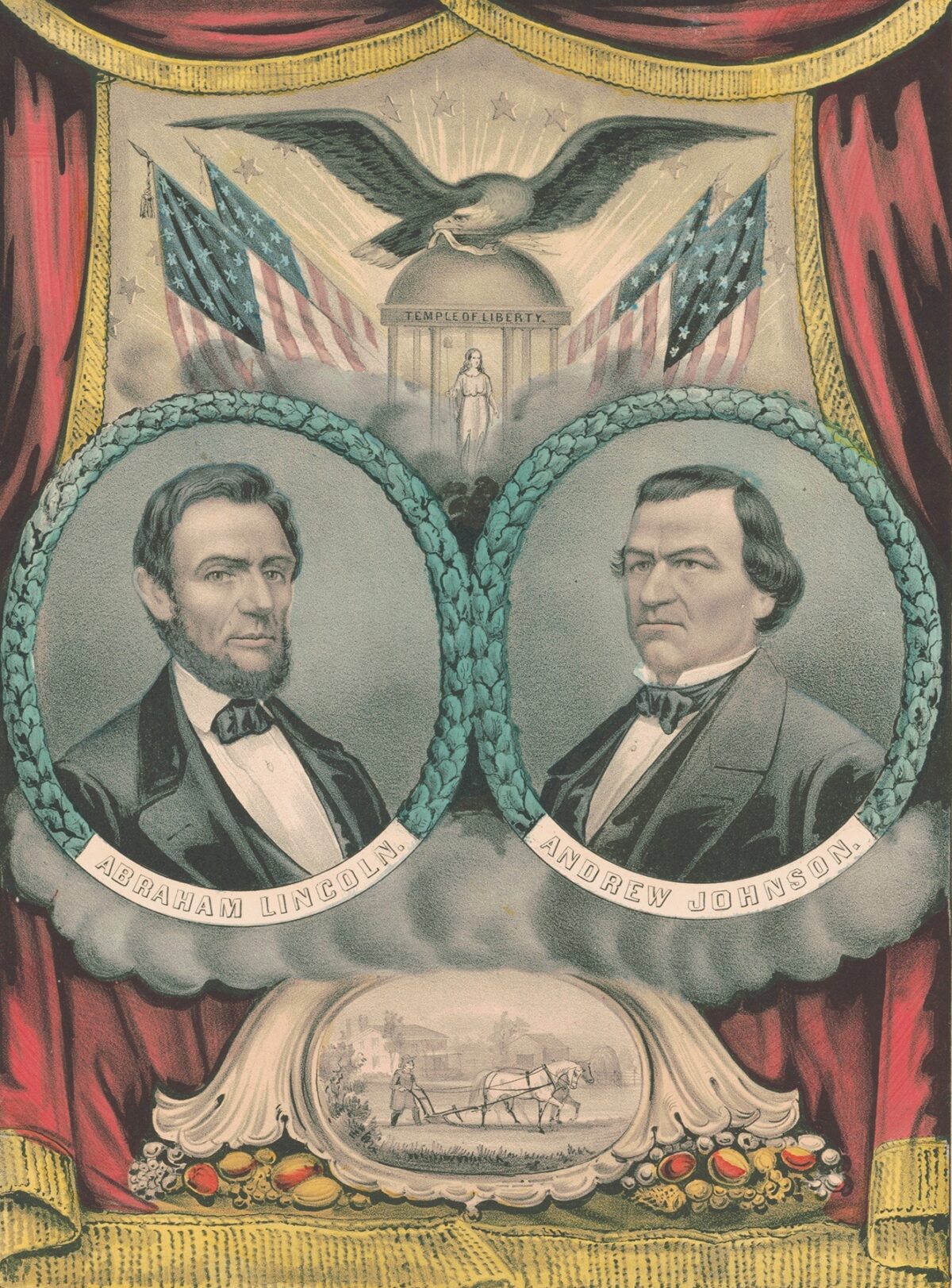

By the time the Republicans—rebranding themselves as the National Union Party in order to attract the support of pro-war Democrats—met in convention at Baltimore in June, the skeptics had run out of options. Lincoln won renomination and the party added pro-Union Tennessee Democrat Andrew Johnson to the ticket as his running mate.

But then the Democratic Party nominated another military man, General George McClellan, to oppose the president. As spring turned into summer, with battle casualties mounting and no peace in sight, most Americans fully expected that Lincoln’s first term would be his last.

The ensuing campaign was by all accounts one of the most vicious in history. Democrats warned that if Lincoln won re-election, African Americans would win equal rights—anathema to many white voters. Republicans countered that a victory by Democrats would destroy the American Union envisioned by the nation’s founders.

On the September day, the Democrats officially chose McClellan as their nominee, not one in a hundred Americans would have predicted he could be stopped. Fully sharing that belief, a glum Lincoln asked his Cabinet members to sign, sight unseen, a pledge to cooperate with the incoming Democratic president to save the Union between Election Day and Inauguration Day, “as he will have secured his election on such grounds that he can not possibly save it afterwards.”

What happened the next few days, however, upended expectations and proved the old political adage that no poll counts until Election Day. Within a breathtakingly short time, voters learned that General Sherman had taken Atlanta. Then readers received the news from Europe that the Union warship Kearsarge had trapped and destroyed the Confederate commerce raider Alabama. Almost overnight, the political equilibrium turned upside down and a relieved and rejuvenated electorate rallied around their president. On Election Day, Lincoln rode to a surprisingly easy triumph. It was one of the most brutal campaigns ever, and one of the most astonishing turnarounds.

But perhaps the most amazing thing about the election campaign that commenced a century and a half ago is that it commenced at all. We tend to take for granted the fact that the presidential contest had to occur as scheduled, but in fact no other country had ever proceeded with a national election in the midst of a civil war. For Lincoln, a president criticized then, and ever since, for suspending civil liberties, the right to vote proved to be one liberty too precious to abrogate. The election would proceed, even if it meant that war-weary voters might choose to oust the Lincoln administration from the White House and, in effect, cede the destruction of the Union and the perpetuation of slavery.

After winning nearly 56 percent of the popular vote and an overwhelming triumph in the Electoral College, a relieved Lincoln responded to a victory serenade that “[T]he election was a necessity. We can not have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us….What has occurred in this case, must ever recur in similar cases.”

So the first time this year you hear a newscaster tell you that no election has ever mattered more than the one we will soon be fighting over, just remember— Abraham Lincoln would want it no other way. After all, he labored to save the Union just so we might continue arguing over politics. As he would see it, we’re not divided. We’re blessed.

Historian Harold Holzer is chairman of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation. His latest book is The History of the Civil War in 50 Objects from the New-York Historical Society (Viking).

Originally published in the May 2014 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.