Steps from remains of Union earthworks and within sight of the “God Tree,” Gettysburg National Military Park archaeologist Erik Kreusch and two volunteers sweep metal detectors over deep-brown earth. “Beep, beep, beeepppp ….” A pricey machine squeals, announcing the presence of metal under hallowed ground, near the crest of Culp’s Hill.

In three weeks, Kreusch and his team have uncovered hundreds of battle artifacts. That’s hardly a surprise, because on July 3, 1863 alone, more than 1.5 million bullets were fired on the hill ¾-mile from the town square, according to one expert. That’s probably more than 100,000 pounds of lead.

To return Culp’s Hill to close to its 1863 appearance, trees and undergrowth were removed beginning in February, opening stunning viewsheds not seen for more than a century. The National Park Service-Gettysburg Foundation partnership was largely funded by California businessman Cliff Bream, a Gettysburg native with deep pockets and deep local roots—his ancestors owned the Black Horse Tavern, a Confederate hospital and staging area near the battlefield.

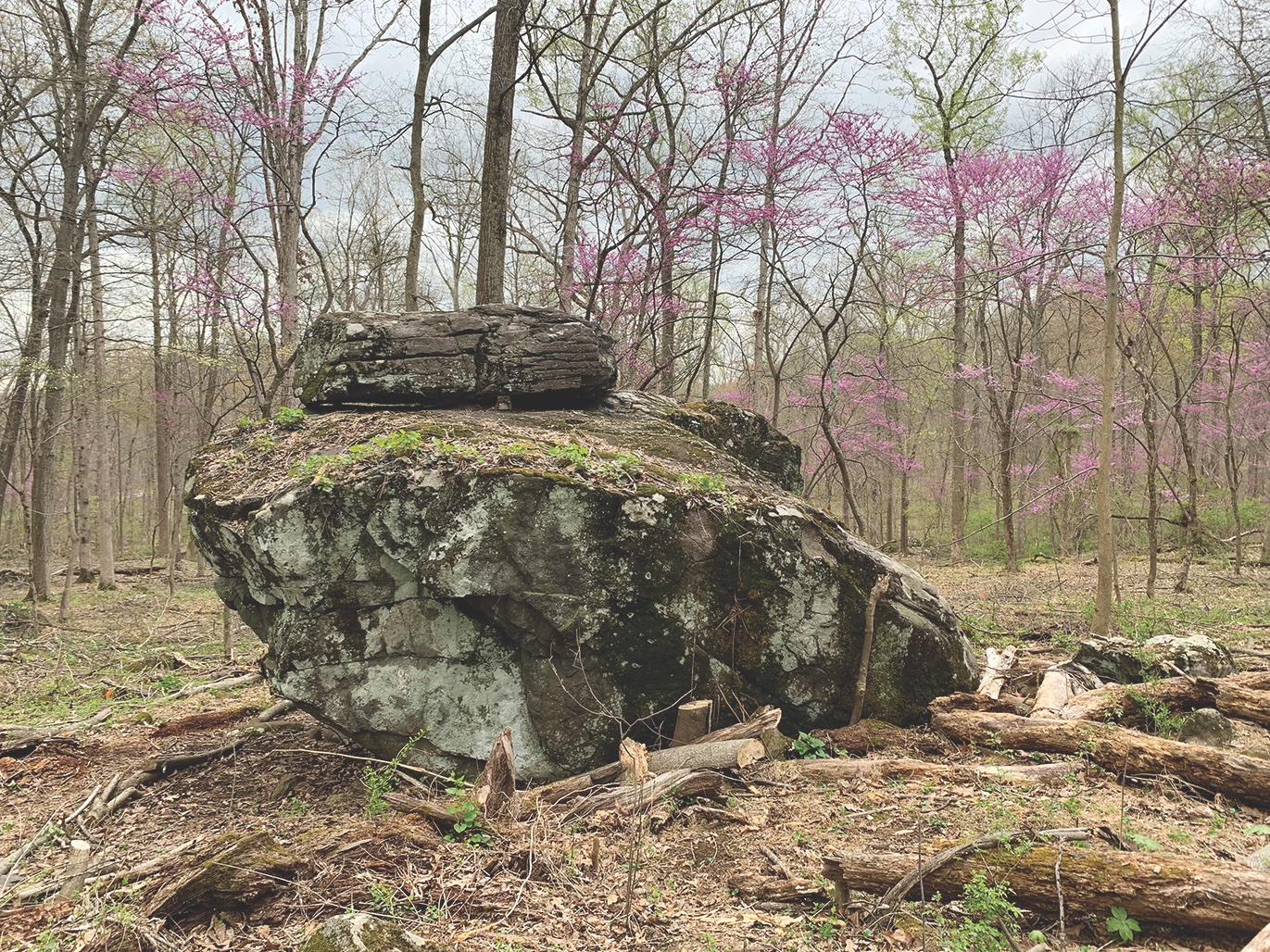

The NPS will add a trail for visitors to massive Forbes Rock, among the most famous boulders on a battlefield studded with them. To comply with Federal law, that project requires the clearance of archaeological materials and a report from Kreusch, a longtime NPS employee with an “I have a sweet gig” grin.

While I visit with the archaeologist, yards away Civil War Times Editor Dana Shoaf and Director of Photography Melissa Winn hover over artifact holes like famished Billy Yanks eyeing a box filled with hardtack. Volunteer Joe Balicki, a retired archaeologist, registers another hit with his $1,200 Equinox 800. Shoaf plunges a shovel into the dirt, then uses a small, orange pinpointer to narrow the location of the find. Moments later, a mangled Confederate bullet reveals itself after nearly 158 years in seclusion.

For Shoaf, it’s ecstasy. For Kreusch, it’s a tiny piece of a giant mosaic…and so much more.

Before we dig deeper into this archaeology story, a brief history lesson: Culp’s Hill—the barbed portion of the “fishhook” of the U.S. Army line—was the only hill on the field that was attacked on all three days during the battle. Although it outnumbered the U.S. Army roughly 3½ to 1 at Culp’s Hill on July 2, the Army of Northern Virginia failed to dislodge the Federals, who fought furiously from behind breastworks. For Confederates, it was a missed opportunity to sever the Army of the Potomac’s vital Baltimore Pike supply line.

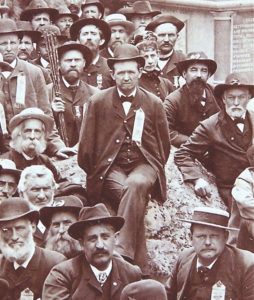

Culp’s Hill was the scene of one of the more remarkable postwar events: On July 3, 1885, 22 years to the day after he lost his arms to friendly fire nearby, 20th Connecticut veteran George Warner unveiled the regiment’s monument. Using a pulley connected to a special device tied around his waist, the married father of five children stepped back several steps to remove a giant American flag from the white granite marker. “Holy and sacred ground,” one of Warner’s comrades called Culp’s Hill in his monument dedication speech that day.

In the first decades after the war, Culp’s Hill was a destination point for visitors, who were drawn by its proximity to Baltimore Pike, bullet-riddled trees, remnants of Federal earthworks…and shade. The wooded hill, actually two rounded peaks separated by a narrow saddle, offered plenty of protection from the sun. In 1906, Culp’s Hill was still open enough for the Pennsylvania State Guards to hold a three-hour reenactment with thousands of soldiers.

Eventually trees and other vegetation obscured the viewshed on Culp’s Hill; and for the past 100-plus years, many battlefield visitors skipped the former grazing ground for farm animals. That’s too bad, because on the crest they missed a monument to underappreciated Union Brigadier Gen. George Sears Greene—a brilliant engineer and one of my favorite Union officers. By ordering his soldiers to build breastworks at Culp’s Hill, 62-year-old “Pappy” Greene helped save the U.S. Army.

A Navy jet mechanic a lifetime ago, Kreusch has worked as a professional archaeologist for 27 years. His resume includes assignments at Fort McHenry in Baltimore, where Francis Scott Key was inspired to write The Star-Spangled Banner during the British bombardment in 1814, and the Chalmette battlefield near New Orleans, where Andrew Jackson’s hastily assembled army whipped the Brits the next year. He loves archaeology and says his Gettysburg job represents the pinnacle of his career—the battlefield he finds inspirational, “a touchstone for talking about our divisions.”

The “holy grail” for Kreusch is tying an artifact directly to an event or person—a Rebel private to the lock plate on a Model 1861 Richmond rifled musket or a fallen Yankee lieutenant to the bullet that killed him. Linking a find to another living human exhilarates.

He tells me the story of an assignment in the Great Smoky Mountains at a Cherokee Indian site that dated to 1350. One of his volunteers, a Cherokee high school student, discovered in a pit a small, green rock, about the thickness of five dimes. It was a fortune-telling stone, the Cherokee version of a Magic 8-Ball you may have played with as a kid. It was a thrilling find for the girl because her grandmother used similar stones.

Few artifacts Kreusch uncovers elicit such a strong, emotional reaction. But every battlefield artifact he and his crew uncover at Gettysburg helps tell a story. Think of Culp’s Hill like a giant puzzle—the bullets, artillery fragments, buttons, and other recoveries are the pieces. Each “piece” enhances an archaeologist’s ability to tell a more complete story. That’s why professionals like Kreusch wince—or worse—when amateurs remove artifacts from Gettysburg or any other battlefield or historic site.

A longtime battlefield preservationist calls relic hunters “vermin.” Their angry reply might be: “What’s the big deal? We seek permission to hunt on private land, document our finds, and have a deep interest in history.” The NPS occasionally has even used amateur archaeologists to help recover artifacts from national parks. But some diggers are in the hobby for less than altruistic reasons—we sometimes read stories of the unscrupulous caught removing artifacts from national battlefields. “Vermin?” Yup. Theft from all of us? Yup. A Federal crime? You bet.

From Spangler’s Spring, Slocum Avenue cuts a serpentine path to the crest of Culp’s Hill. In a roughly 500-square foot area near Forbes Rock, a short distance from the park road, Kreusch’s crew works the ground; to our left, about 15 yards away, Mathew Brady shot an image in mid-July 1863 of his assistants gazing at the battle-scarred landscape. Dozens of white flags mark recent archaeological finds, each stashed in a small plastic bag.

The work of Kreusch and his volunteers is—no pun intended—ground-breaking. It’s the first systematic archaeological work at Culp’s Hill in the national military park’s 126-year existence. For now, their search is confined to ground the NPS plans for a pathway through the woods. Ongoing archaeological efforts on the rest of Culp’s Hill will take years to complete.

Among finds by Kreusch’s crew are percussion caps, a button and small buckle from a forage cap, a Company I insignia, and a New York state button with a green patina. Behind Union earthworks, six Confederate Gardner bullets and a piece of leather revealed themselves. Kreusch speculates those rounds were in a pouch dropped by a prisoner as he was hauled over U.S. Army earthworks. Uncovered nearby were a cartridge box and more than a dozen unfired Miniés—the most impressive recovery thus far.

Oh, my, why did I choose journalism for a career?

The concentration of fired and unfired bullets on a battlefield can tell an archaeologist about the ferocity of fighting, troop strength, weapons used, and much more. A bullet’s orientation in the ground may denote its firing point. Were some of the Kreusch team’s recoveries discharged from nearby Forbes Rock, used by Confederates for cover on the night of July 2? A tree in Brady’s image of the massive boulder clearly shows evidence of Union return fire.

Two Culp’s Hill bullet finds—a Sharps fired into U.S. Army breastworks and a full Spencer cartridge—pique Kreusch’s interest. In 1863, Confederates were not generally known to have Sharps rifles. Was a Union cavalryman picketing on Culp’s Hill with a Spencer carbine? The weapon wasn’t demonstrated to President Lincoln on the lawn of the White House by its inventor until after Gettysburg. Hmmm.…

Perhaps bullets also remain in the now-decrepit “God Tree,” which in a misguided preservation effort more than 100 years ago was filled with concrete and rebar. (“Horrible,” Jason Martz of the NPS, our Culp’s Hill guide, tells me.) Areas near Union earthworks where relatively few battle artifacts are found also may tell a story. Were they safe havens in the storm of Confederate lead on the evening of July 2, 1863?

At the national cemetery’s former caretaker’s lodge, nerve center of Kreusch’s operation, two large, plastic tubs hold hundreds of bags of Culp’s Hill artifacts. Each find will be cleaned and analyzed. Bullets may be subjected to ballistics tests. Using computer technology, a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) map of the finds will be created. Kreusch will write a report about his team’s discoveries. The entire process may take as long as six months.

For Kreusch, new archaeological adventures at Gettysburg await—at Devil’s Kitchen on Big Round Top’s lower slope; at Devil’s Den and Spangler’s Spring; and at the Josiah Benner farm, a U.S. Army hospital site, and elsewhere.

Oh man, I can dig it. ✯

John Banks, who lives in Nashville, is author of a popular Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com). On his only relic-hunting adventure, he found a fired bullet on private land at Antietam.