Under the stern but sympathetic gaze of Lt. Col. Louis Wagner, some 11,000 African-American soldiers trained to fight for their freedom at Philadelphia’s Camp William Penn. Three Medal of Honor recipients would pass through the camp’s gates.

Major Louis Wagner of the 88th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment knew that his situation was desperate when a Confederate bullet shattered his right shin at the Second Battle of Bull Run on the afternoon of August 30, 1862. The fight had been raging ferociously since noon, with Southern fire slamming relentlessly into Union soldiers commanded by Major General John Pope. That night the defeated Northern army retreated toward the safety of Washington, leaving behind some 16,000 casualties.

One of those casualties, 24-year-old Louis Wagner, would be taken prisoner by the victorious Rebels and later paroled to his Philadelphia home. The German-born Wagner, despite his youth, had been a shining star ever since he enlisted at the outbreak of the war, rising steadily in rank and prestige. By the time he was wounded at Second Bull Run, he had already fought valiantly at Cedar Mountain, Rappahannock Station, Thoroughfare Gap and Groveton.

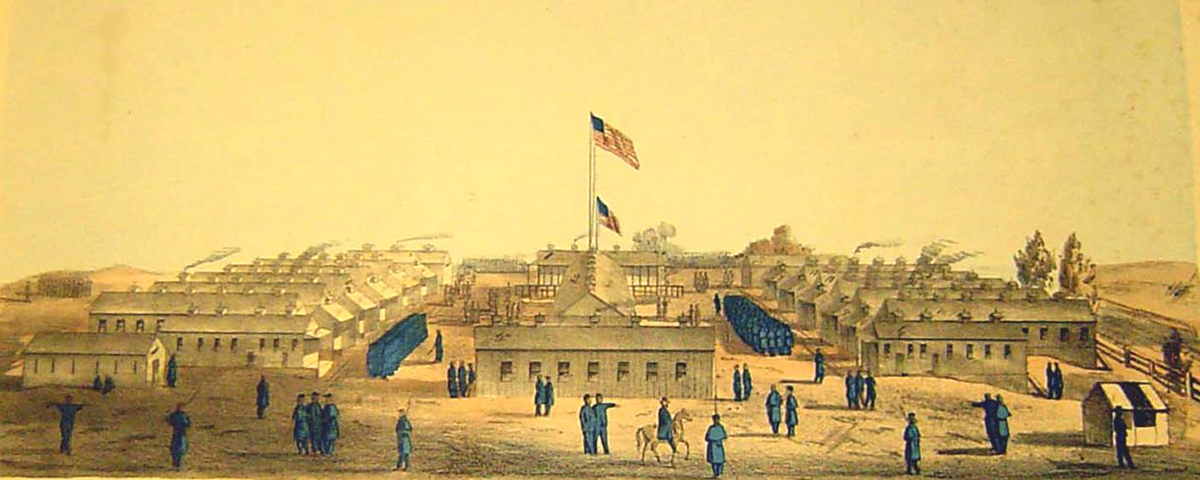

Before his wound had sufficiently healed, Wagner returned to the front in preparation for the Battle of Chancellorsville. His hasty return aggravated his wound, and Wagner returned home to Philadelphia, unfit for further field duty. The determined young officer did not return to his civilian occupation of lithographic printer. Instead, in early 1863 he volunteered to take command of Camp William Penn, the first and largest Federal training facility for African-American soldiers.

When President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation freeing the slaves held in Confederate states took effect on January 1, 1863, thousands of free blacks and ex-slaves rushed to enlist in the Union Army. Many poured through the gates of Camp William Penn, about 10 miles north of downtown Philadelphia in the rolling, green Pennsylvania countryside. First Lieutenant Oliver Willcox Norton of the camp’s 8th United States Colored Troop (USCT) Regiment, formerly a private in the 83rd Pennsylvania, later described the enthusiasm of the black recruits. “Our camp thronged with visitors…who wanted to enlist,” he wrote. “There are hundreds of them, mostly slaves, here by now, anxiously waiting for the recruiting officer. The boys are singing: ‘Rally round the flag, boys, rally once again, shouting the battle cry of freedom; down with the traitor, up with the star.'”

Despite the lingering pain of his injury, Wagner took command and personally helped drill the camp’s first new recruits. Although unable at times to walk, the newly minted lieutenant colonel had himself lifted into the saddle on his horse as he readied the 3rd USCT for what he knew would be a soul-testing career in the Union Army. Not only would the new troops have to face battle-hardened Confederate veterans, but they would also encounter the resistance of racially motivated opponents at home.

Although Philadelphia was a stronghold for abolitionist activities, many eastern Pennsylvanians harbored deep-seated racism. More than two decades earlier, in 1842, the great African-American orator Frederick Douglass had been pulled from his train seat by an irate white passenger after giving a speech in nearby Norristown. Trains and streetcars were segregated then, and blacks were not allowed to sit inside the vehicles. Instead, they had to stand outside between the cars. After reaching the state capital at Harrisburg, Douglass was attacked by a white mob and barely escaped with his life.

Camp William Penn had been formally mandated by the federal government after state and local authorities had refused to start their own camp for black troops. An estimated 1,500 African-American volunteers from the Philadelphia area had traveled north to enlist in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first famous black regiment, because of racist opposition in the so-called City of Brotherly Love. Sometimes black soldiers from Camp Penn were beaten unmercifully by white mobs if they were caught in the wrong part of town.

At the same time, racist Copperheads nearly burned down Philadelphia’s Union League, a Republican institution with many anti-slavery members. Copperheads were Southern sympathizers who did not appreciate the league’s role in raising funds to organize and train black troops in the city. One prominent Union League member was Chelten Hills resident Jay Cooke, a multimillionaire who sold so many bonds to finance the Union war machine that he became known as “the financier of the Civil War.” Another member was Edward M. Davis, son-in-law of the famed Quaker abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Lucretia Mott, whose family leased the land to the federal government to erect Camp William Penn. The petite Mott often spoke to the troops at the camp while standing on a drumhead, and she baked cakes and pies for the men.

When Frederick Douglass entered the grounds of Camp William Penn on the afternoon of Saturday, July 18, 1863, he was greeted by a disturbing sight. As the legendary black leader prepared to speak, he saw a number of black recruits standing atop barrels with rails over their shoulders as punishment for various military infractions. Douglass was clearly angry when he began to address the troops of the 3rd Regiment because he had learned that some of the men–many bearing the scars of slavery–were giving their white officers plenty of trouble. One disgusted officer condemned the ability of the black recruits to become good soldiers.

“The fortunes of the whole race for generations to come are bound up in the success or failure of the 3rd Regiment of colored troops from the North,” Douglass told the troops. “You are a spectacle for men and angels. You are in a manner to answer the question, can the black man be a soldier?” His confident voice rising, Douglass continued, “That we can now make soldiers of these men, there can be no doubt!”

The imposing Douglass–standing more than six feet tall and weighing about 200 pounds–knew all too well how much the destiny of blacks in America rested on the shoulders of newly enlisted black soldiers. That very evening, one of Douglass’ own sons was putting his military training to good use by taking part in the bloody assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina as a member of the 54th Massachusetts. The 54th would be repelled and suffer terrible casualties, but the regiment proved conclusively that blacks were brave warriors.

Douglass knew that skeptical local antagonists would still closely scrutinize events at Camp William Penn. For that reason, the rebellious attitude of some of the black soldiers in camp worried him greatly. Although he realized that some of their defiant actions were at least partially justified due to abuse by whites at the camp, he also knew that there was much at stake for the soldiers and the local abolitionists who had stuck their necks out for them. Douglass would temporarily stop recruiting due to the abuses and meet with President Lincoln about the problem, but he wanted the new black soldiers to look at the larger picture while fighting in a constructive way for their human rights. Right in the Chelten Hills community where they were pre-paring for war, abolitionists such as Mott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Harriet Tubman, William Lloyd Garrison and others were helping to lay the groundwork that would lead to the expanded emancipation of black Americans.

Standing near the camp’s white commander, Louis Wagner, Douglass replied to white pessimism about the black troops. His African brethren were ready and willing to fight and die for their emancipation, he insisted. But Douglass also said that the black recruits should not defy government authority. Addressing the black troops, he told them, “It is for you to justify that reply, which I certainly believe you will do, but in order to [do] this you will have to prove that you cannot only parade and drill, but equal the white soldiers in deportment, in neatness of person, in the brightness of your arms, in orderly deportment, and scrupulous obedience to orders.”

It was not that he did not understand the soldiers’ problems. Douglass had a special respect for the men standing before him, many scarred and mangled for life by years of slavery. He had shared their agonizing past and knew their pain. Underneath his garments, on his back, he wore a stark reminder: horrible scars caused by the flesh-slicing whip of a Maryland slave overseer.

It was not long before the black men standing at arms before Douglass would prove themselves quite worthy of carrying the U.S. flag into battle. But they still had to face trouble at home first. In fact, before leaving the Philadelphia area on September 18, 1863, the 3rd Regiment would endure further humiliation. Because of continuing racism, the regiment was not allowed to parade in the city. The August 8, 1863, edition of the Christian Recorder, a black newspaper published in Philadelphia by the African Methodist Episcopal Church, explained the situation: “At the latter part of last week several of our daily papers published the gratifying intelligence that the Third Regiment of Philadelphia Colored troops would come into the city from Camp William Penn, to go through the evolutions of a street parade. The day came, but with it also came the postponement of the promised treat indefinitely. This has been a source of grievous disappointment to a great many, both colored and white.”

The Christian Recorder noted the 3rd Regiment’s great anger about not being able to parade shortly before it departed. “[N]ot only were the friends of the regiment disappointed, but when the intelligence reached the encampment it caused a great commotion amongst the men, amounting, as we have been told, almost to a state of mutiny, which had been the consequences of so frequently disappointing the men on this account,” the Recorder report said. “What right any man has to interfere with colored, more than with white troops, we cannot conceive. Does the government want to get them up in some dark corner, and prepare them to do just what white men are prepared to do in the dark? It should be remembered, that these men are human beings, and have their five senses, and feel just as well as the whites do. They are not ignorant of the manner in which they are treated; and of course they know what they are, and the kind of treatment they deserve. And the men who would interfere with, or molest them in any way, deserve the severest punishment. We, therefore, hope that both the Government and Philadelphia will redeem themselves from last week’s doings.” The disappointed 3rd Regiment, under Colonel Benjamin C. Tilghman, eventually marched off to war, participating in the siege of South Carolina’s Fort Wagner and in several important Florida battles.

One black soldier, upset with unfair treatment in the Philadelphia region and especially at Camp William Penn, wrote a moving letter to President Abraham Lincoln complaining about his treatment. His white officers, the soldier explained, would not let him vote and would not let him go home when he was sick. “We had boys her that died and wood gout [would have gotten] well if thy could go home,” the soldier said. “[They] can come back as well as a white man.” The camp’s white officers and recruits elsewhere were allowed to go home to recover when they were severely ill, he complained, but not the black recruits.

Another camp recruit also complained of his unsympathetic officers. “My left leg is very badley afected from an old cut and the surgent here have bin giving me…Leinament to rub it with and it is well mixt with turpentine,” he wrote. “I hav bin useing it until I have almost lost the use of my leg.I have tole him often that it was getting worse, but he will driv me off like a dog and say that he can’t do anything for me.”

Although soldiers sometimes complained about receiving harsh treatment, some members of the local community recognized that Camp William Penn symbolized an important advancement for the African-American community. For instance, Lucretia Mott wrote about the camp in a letter to her sister in 1863. “The neighboring camp seems the absorbing interest just now,” Mott wrote, although she was a staunch pacifist who claimed to support the necessity of combating pro-slavery forces via preaching and advocacy but not by resorting to physical violence. “Is not this change in feeling and conduct towards this oppressed class beyond all that we could have anticipated, and marvelous in our eyes?”

Camp commander Wagner supported his black troops, despite frequent public pressure. Local newspapers wrote several accounts of a black soldier guarding the post who shot a belligerent white man intent on entering the camp without permission. Although the white community became enraged and demanded the black soldier be brought to trial in nearby Norristown, the Montgomery County seat, Wagner refused to hand him over.

Wagner also insisted that his black soldiers ignore segregationist policies and ride beside him on local trains. Braving opposition, he also paraded the next regiment to leave the camp for battle, the 6th USCT, right down Philadelphia’s main thoroughfare, Broad Street, and past the Union League’s front steps filled with dignitaries and top military brass.

“There was an immense crowd of white and colored [who] followed them through the streets,” the Christian Recorder reported. “We were somewhat amused while standing on the corner of Third and Walnut to hear some person remark, ‘Here comes the flag of distress.’ Some white men were in the crowd, and one well-dressed heavy-set gentleman, whom we took to be a German, although he spoke good English, exclaimed, ‘What did you say, sir? I’ll let you know, sir, that it is the American flag, and it is time you had learned enough to that effect, and if you don’t know it, I can quickly teach you.’ The poor fellow looked bad and hung his head when he saw those who stood around him look upon him with contempt; but the gentleman who addressed himself to him looked with as much indignation as to say if the poor ignorant fellow would have said so again he would have felled him to the ground.”

Another eyewitness gave an account of the 6th Regiment’s parade: “Walnut, Pine and Broad Streets listened to the measured tread of the dusky soldiers and the staccato of a full drum corps. The Union blue, the white gloves and the glint of fixed bayonets contrasted sharply with the dark faces perspiring under the rays of a warm October sun.

“As the regiment passed the Continental Hotel, a city tough ran out from the crowd and snatched the color away from the sergeant, who knocked the intruder down, rescued his flag, and resumed his place in the ranks, to the cheers of many of the spectators.”

The unit’s regimental flag, designed by the famed black artist David Bustill Bowser and depicting the Goddess of Liberty holding a flag while exhorting a freedman dressed as a soldier to do his duty, would soon face other such tests during the heat of battle.

Almost a year after marching down Philadelphia’s Broad Street and then sailing south by boat, Nathan H. Edgerton was among more than 350 soldiers in the 6th Regiment to run into a deadly hail of Confederate bullets at the Battle of New Market Heights (Chaffin’s Farm) in Virginia on the chilly and foggy morning of September 29, 1864. More than 60 percent of the regiment’s men, trained at Camp William Penn, would die in that battle.

That morning, the 6th USCT had rushed toward a line of Rebel fortifications manned by the hardened veterans of Colonel Frederick M. Bass’ Texas brigade. Dozens of Edgerton’s comrades had been hit and had fallen, including most members of the color guard, when Lieutenant Frederick Meyer of Company B seized the colors and a bullet slammed through his heart and killed him. Meyer, however, maintained a death grip on the staff.

“I took it from him and pushed forward to bring up the colors to their proper place,” Edgerton later recalled. “All at once I went down, but jumped up immediately and tried to raise the flag, for I thought I had fallen over the dewberry vines which grew thickly there, but finding it did not come, I looked down, after trying again, to see why I could not lift it, and found my hand covered with blood, and perfectly powerless, and the flag-staff lying in two pieces. I sheathed my sword, took the flag with its broken staff and reached the abatis.”

When Edgerton began to reel and stumble due to the loss of blood, Sergeant Alex-ander Kelly of Company F grabbed the flag and carried it from the field. Edgerton mi-raculously survived his wound. Under similar conditions that day, Sgt. Maj. Thomas Hawkins of Company C also retrieved the flag. All three eventually received the Medal of Honor for their bravery.

Major General Benjamin F. Butler was thoroughly impressed with the black troops’ bravery at New Market Heights. “Better men were never better led, better officers never led better men,” Butler said. “A few more such charges and to command colored troops will be the post of honor in the American armies.”

The 6th Regiment was not the only Camp William Penn regiment to fight courageously in bloody campaigns. The 22nd and 8th USCT regiments also lost many men during the New Market Heights fray.

Six months earlier, on February 20, 1864, the 8th had lost a huge share of its men in an engagement at Olustee, Fla. At the time, the regiment had little battlefield experience, being barely a month out of Camp William Penn. At Olustee the 8th, commanded by Colonel Charles W. Fribley, suffered terrible casualties, including 343 killed, wounded or missing in action. A letter written by 1st Lt. Oliver Willcox Norton detailed what happened when troops of his Company K marched near a strategic railroad line. “The skirmishing increased as we marched, but we paid little attention to it,” Norton wrote. “Pretty soon the boom of a gun startled us a little, but not much as we knew our flying artillery was ahead, but they boomed again and again and it began to look like a brush. An aide came dashing through the woods to us and the order was ‘double quick, march!’ We turned into the woods and ran in the direction of the firing for half a mile, when the head of the column reached our batteries.

“Military men say it takes veteran troops to maneuver under fire, but our regiment with knapsacks on and unloaded pieces, after a run of half a mile, formed a line under the most destructive fire I ever knew. We were not more than two hundred yards from the enemy, concealed in pits and behind trees, and what did the regiment do? At first they were stunned, bewildered and knew not what to do. They curled to the ground, and as men fell around them they seemed terribly scared, but gradually they recovered their senses and commenced firing. And here was the great trouble–they could not use their arms to advantage. We have had very little practice in firing, and, though they could stand and be killed, they could not kill a concealed enemy fast enough to satisfy my feelings.

“After seeing his men murdered as long as flesh and blood could endure it, Colonel Fribley ordered the regiment to fall back slowly, firing as they went. As the men fell back they gathered in groups like frightened sheep, and it was almost impossible to keep them from doing so. Into these groups the rebels poured the deadliest fire, almost every bullet hitting some one.”

Colonel Fribley was shot and killed after his order to retreat. “We were without a commander,” wrote Norton, “and every officer was doing his best to do something, he knew not exactly. There was no leader.”

Norton later noticed that he had five holes in his hat, which he claimed were caused by a single bullet. “My hat was cocked up on one side so that it went through in that way and just drew the blood on my scalp,” he wrote. “Of course a quarter of an inch lower would have broken my skull, but it was too high.”

Norton noted that “Company K went into the fight with fifty-five enlisted men and two officers. It came out with twenty-three and one officer. Of these but two men were not marked. That speaks volumes for the bravery of Negroes. Several of these twenty-three were quite badly cut, but they are present with the company. Ten were killed, four reported missing, though there is little doubt they are killed, too.”

Confederate soldiers hated commanders of black regiments such as Wagner and Fribley. If such Union leaders were captured during battle, they were often slaughtered along with their black troops instead of being taken prisoner. When Confederate Brig. Gen. William Gardner decided to send some of Fribley’s personal belongings to his widow, he noted, “That I may not be misunderstood, it is due to myself to state that no sympathy with the fate of any officer commanding negro troops, but compassion for a widow in grief, had induced these efforts to recover for her relics which she must naturally value.”

Less than a month after the September 29 engagement at New Market Heights, future Medal of Honor recipient Nathan H. Edgerton lay recovering in the Chesapeake Hospital near Fort Monroe. In a letter sent on his behalf to the surgeon general’s office, Edgerton asked to be transferred to one of the hospitals in Philadelphia, because his “parents reside in Philadelphia, and are very anxious to have him near them.”

The correspondence also stated that Edgerton “was wounded severely in the right hand…while carrying the colors of his regiment, and acting as adjutant. He has been recommended for promotion for gallantry in the field, and will shortly receive his commission as 1st Lieutenant.” The order to send Edgerton back to Philadelphia came just two days later, on October 23. He was quickly promoted, and he later served as adjutant.

As the Civil War drew to a close, a charismatic black woman strode in front of hundreds of black soldiers at Camp William Penn and delivered a stirring speech. She was the well-known ex-slave and freedom fighter Harriet Tubman, who had come to inspire the black soldiers of the 24th Regiment, the last of Louis Wagner’s regiments to leave the camp for war.

Tubman was a wanted woman by Confederate authorities. She had made many trips into the Deep South and escorted hundreds of runaway slaves to freedom via the Underground Railroad that extended through Chelten Hills, Pa. There was a $40,000 reward on her head.

Like Douglass and many of Camp William Penn’s soldiers, Harriet Tubman was an escaped slave with the scars of slavery on her body. Although she spoke a slave dialect and not standard English, she greatly inspired the men that day, according to a Christian Recorder article. The camp, said the newspaper, “had a very entertaining homespun lecture from a colored woman known as Harriet Tubman. It was the first time we had the pleasure of hearing her. She seems to be very well known by the community at large, as the great Underground Rail Road woman, and has done a good part to many of her fellow creatures, in that direction.

“During her lecture, which she gave in her own language, she elicited considerable applause from the soldiers of the 24th Regiment…now at the camp. She gave a thrilling account of her trials in the South, during the past 3 years, among the contrabands and colored soldiers, and how she had administered to thousands of them, and cared for their numerous necessities.”

Around the time that Tubman spoke to the 24th Regiment, the camp’s 43rd USCT joined the pursuit of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, after participating in the capture of Petersburg, Va. The 43rd, along with other black regiments trained at Camp William Penn, finally caught up with Lee and were present during his April 9, 1865, surrender at Appomattox Court House. Meanwhile, the 22nd USCT, which also hailed from Camp William Penn, helped to corner President Lincoln’s assassins along the eastern shore of Maryland and the lower Potomac after a lengthy pursuit from April 15 through the first part of May 1865.

The war was finally over. After the great conflict, Benjamin F. Butler, who had pushed from the start for black men to fight with Union forces, spoke for many when he said the African-American soldiers had “with the bayonet…unlocked the iron-barred gates of prejudice, and opened new fields of freedom, liberty, and equality of right.”

La Mott, Pa., journalist Donald Scott lives in the same neighborhood where Fort William Penn once was located. For further reading, see: The Negro’s Civil War, by James M. McPherson; or The Negro in the Civil War, by Benjamin Quarles.

This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.