“Practical bee-keeping in this country is in a very depressed condition…and success is becoming more and more precarious,” Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth wrote at the start of his 1853 book, The Hive and the Honeybee: A Beekeeper’s Manual. In his 500-plus-page handbook the Yale alumnus described the handful of hurdles then facing beekeepers, a sharp contrast with today’s storm of threats to bees. But Langstroth, a Congregationalist minister turned apiarist, went beyond advice and theory. No matter what threatens their bees, beekeepers need to be able to see what is going on inside a hive in order to inspect and manage it well. A hive design that Langstroth created in 1852 made such monitoring possible and remains the basis for the design of today’s most commonly used hives.

Insects so fascinated Langstroth as a child that he is said to have worn holes in his pants kneeling to observe them. But he was 27 before he purchased his first beehive. Hives then were inscrutable, with bee colonies housed in wooden boxes or containers of straw known as skeps. To remove the honeycomb—in the mid-19th century the form in which honey was consumed—an apiarist had to wreck the skep or break the comb free from the sides of the box, angering the bees and jeopardizing the beekeeper.

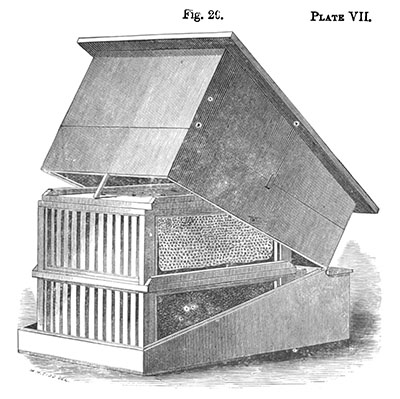

Langstroth, who tended toward disabling melancholy, spent a dozen years watching and tinkering. The process seemed to focus his mind and helped stave off the mysterious mood disorder that would eventually end his career in the ministry. He built observation hives with glass components that rendered the internal action visible. His most crucial discovery was that if he left 3/8 of an inch between frame and hive wall, bees would not build comb in that space but use it to move about. Langstroth called this gap “bee space” and wrote that his observation of bee space led him “to invent a method by which the combs were attached to movable frames, so suspended in the hives as to touch neither the top, bottom, nor sides. By this device the combs could be removed at pleasure, without any cutting, and speedily transferred to another hive.” In a Langstroth hive, a beekeeper could remove and inspect frames as easily as papers in a filing cabinet.

At the time, apiarists relied for guidance on a handbook in German by Polish priest and apiarist Jan Dzierzon. Beekeeper Samuel Wagner, then translating Dzierzon’s work into English, was so impressed upon seeing Langstroth’s design at the innovator’s home in Philadelphia that he abandoned his translation and urged Langstroth to write a manual of his own. A year later, Langstroth had completed The Hive and the Honeybee. In 1863, Wagner founded the American Bee Journal, the oldest English-language bee journal still in existence, and hired Langstroth as a contributor.

Before Langstroth reimagined beekeeping, hives were a household phenomenon, not a business. North America is home to bees, but few such species produce honey. Honey-making European bees arrived with English colonists at Jamestown, Virginia. Households commonly tended hives to get honeycomb as a sweetener and beeswax for candles. Native Americans came to call the honeybee “the white man’s fly,” and by 1793 the species was encountered as far west as the Mississippi River.

The Langstroth hive made beekeeping a profitable trade, first in honey and wax and then in bees themselves. Langstroth’s stackable, easy-to-inspect hive—with moveable frames and a top opening—helped recast bees as pollinators of commercial crops, a mainstay of today’s commercial beekeeping. But commercial pollination has emerged as a threat to bees. When bees pollinate, say, almond trees in California, then move, often by the hundreds of hives, to apple orchards in Michigan, nutrient deficits due to feeding on only one type of plant at a time—as well as exposure to pesticide-contaminated pollen—can weaken them. Massed hives coping with the stress of intermittent movement are more vulnerable to mites and viruses. In recent years, beekeepers—commercial and hobbyist alike—have lost as many as 40 percent of their hives.

It would sadden Langstroth to learn that beekeeping is now in greater jeopardy than in 1853. He made educating beekeepers his life’s work, and he drew from a deep well: His library contained 61 books on beekeeping, including one dating to 1579. He learned through every sense, even noting in his manual the taste of what queen bee larvae ate.

“The young queens are much more largely supplied with food than the other larvae; so that they seem to lie in a thick bed of jelly, a portion of which may usually be found at the base of their cells, soon after they have hatched,” Langstroth wrote. “Unlike the food of the other larvae, it has a slightly acid taste; and when fresh, resembles starch; when old,

a light quince jelly.”

This story was originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.