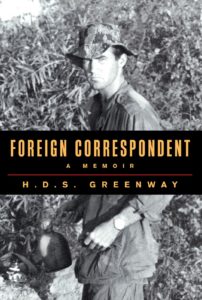

A Naval Reserve officer, David Greenway started his career as a Time magazine war correspondent in Indochina in spring 1967. “It was Vietnam that obsessed me then,” Greenway said, and he acquired a reputation for being lucky. His luck ran out in Hue during the Tet fighting in February 1968, when he was hit in the leg while helping to carry a wounded Marine.

In spring 1972, Greenway found himself back in Hue during the Easter Offensive. “American combat troops were mostly gone, and it was going to be South Vietnam’s big test to see whether they could hold their own with American air and logistic support,” he said. The North Vietnamese Army launched one of its attacks along the My Chanh River after the fall of Quang Tri City. Greenway wrote, “Would the South Vietnamese flee as they had done at Quang Tri?” The South Vietnamese marines, armed with new wire-guided antitank missiles, fired again and again. “It was quite a night, but the My Chanh line held,” Greenway reported.

In spring 1972, Greenway found himself back in Hue during the Easter Offensive. “American combat troops were mostly gone, and it was going to be South Vietnam’s big test to see whether they could hold their own with American air and logistic support,” he said. The North Vietnamese Army launched one of its attacks along the My Chanh River after the fall of Quang Tri City. Greenway wrote, “Would the South Vietnamese flee as they had done at Quang Tri?” The South Vietnamese marines, armed with new wire-guided antitank missiles, fired again and again. “It was quite a night, but the My Chanh line held,” Greenway reported.

Two months later, he was offered a job with the Washington Post. In an excerpt from his recently published memoir, Greenway looks back on what he saw as the war was winding down.

The Americans Depart

Upon joining the Washington Post in the summer of 1972, I moved my family to Washington. One of my first assignments was to cover a press conference that Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had called in October of 1972 in which he stunned the world with the words “peace is at hand.” At long last the North Vietnamese, after torturous negotiations in Paris, had agreed to a cease-fire on our terms, he said. For those of us in the audience who had reported from Vietnam, it was an electrifying moment.

We didn’t learn until later that Kissinger had trouble explaining the terms of his peace treaty to South Vietnam’s president, Nguyen Van Thieu. When he did so, Kissinger cabled President Richard Nixon from Saigon to say: “We face the paradoxical situation that the North, which has effectively lost, is acting as if it won; while the South, which has effectively won, is acting as if it has lost. One of the major tasks now is to restore realities and get the psychological upper hand.” Kissinger thought that Thieu did not understand the scope of Hanoi’s concessions. But Thieu understood the situation better than Kissinger.

“The issue is the life and death of South Vietnam and its 17 million people,” Thieu told the American ambassador, Ellsworth Bunker. “Our position is very unfortunate. We have been very faithful to the Americans, and now we feel as if we are being sacrificed….If we accept the document as it now stands we will commit suicide…and I will be committing suicide.”

Thieu was right. The fatal flaw in Kissinger’s peace deal was that it allowed the North Vietnamese to maintain their forces deep inside South Vietnam, effectively outflanking the South and putting the Central Highlands in peril should the North Vietnamese decide to attack again in defiance of the treaty, which is exactly what they did.

To be fair to Kissinger, he thought that if the North Vietnamese cheated on the peace agreement, the entire might of the United States could come down hard on the cheaters. But even as Kissinger was negotiating in Paris, the political will to continue the war was crumbling in the United States. American troops were leaving, and Congress effectively ended America’s retaliatory capabilities by banning any further airstrikes the following summer.

After some months, the Post named me as its bureau chief in Hong Kong, where my family settled, but it was to Saigon that the Post sent me early in 1973. I soon discovered Kissinger’s cease-fire was in name only. Vietnamese on both sides were still dying because each side was trying to consolidate its position and expand its territory. The agreement allowed forces to stay in place, so both sides raised their flags over the territory they controlled. Traveling around the countryside, I was interested to see how many districts were flying Viet Cong flags. Many of the areas that the Americans had thought pacified and solidly under government control were not.

In accordance with the treaty, American troops were to leave Vietnam forthwith. On March 30, 1973, the last contingent departed from Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Airport aboard a silver C-141 Air Force jet shortly after 5 p.m.

It was a day of ceremonies and speechmaking. Upon closing down Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, General Frederick Weyand stood at attention in a sunbaked parking lot while a recording of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was played over a loudspeaker. The general said that the United States had accomplished its mission to “prevent an all-out attempt by an aggressor to impose its will through raw military force.” He said that the “rights of the people of the Republic of Vietnam to shape their own destiny and to provide for their self-determination has been upheld.” Thieu thanked the Americans for all they had done in “this historic struggle.”

An ugly scene, perhaps more rich in symbolism than the official speeches, took place when a couple of hundred Vietnamese civilians broke through the wire even before the last American had departed. They looted the commissary, and in minutes they had dragged out tables, chairs, fans, canned goods—everything that wasn’t bolted to the floor and some things that were. South Vietnamese military police helped them move the stolen goods through the wire.

Because the Viet Cong were anxious to legitimize their areas of control in that spring of 1973, there was an opportunity to interview them that hadn’t been possible before. Frances FitzGerald, a journalist on assignment for the New Yorker, and I hatched up a scheme to visit the Viet Cong in their forest lair in the contested province of Chuong Thien, deep in the Mekong River delta.

We drove the Washington Post’s car deep into the delta and outside a small village called Long My. This was a sort of no-man’s-land between government-controlled areas and the territory of the Provisional Revolutionary Government, as the Viet Cong called themselves. We had sent a small boy into the forest to make contact for us, taking a message saying we were American journalists who would like to tell their story to the world.

After a wait that seemed hours long, armed men began to emerge from the tall grass at the forest’s edge. I was very nervous. They were surprisingly young. Only a few carried AK-47s, the standard Soviet assault rifle. Most were armed with captured American M16 rifles and grenade launchers. They carried American field radios too, and most wore dressy Seiko watches with expansion wristbands such as could be bought in the better shops in Saigon.

There seemed to be some question of whether we were prisoners or guests, but eventually we were brought to a jungle camp, where a handsome man, obviously in authority, said: “We welcome you, and it does not matter if you are journalists or CIA because we have won the war.” Just before midnight we were told that a senior official would receive us now.

He was clearly an educated man. His conversation ran from battle to Vietnamese poetry. His drift was the absolute conviction that they had won the war. The importance of the Paris agreements was that the Americans had admitted their defeat. I contrast this certainty on the part of the Viet Cong with what the Americans were saying at the time. General Creighton Abrams thought Hanoi was agreeing to peace “because they [have] lost and they [know] it.” But the men of the forest thought otherwise. The Paris accords were just another milestone in the long history of Vietnamese fighting foreigners, said our host. The Americans were simply going the way of the “Mongols, the Chinese, the Japanese, the French.”

These Provisional Revolutionary Government officials made no effort to hide the fact that the North Vietnamese Army was also in the region. The Northerners had come to help their brothers in the South, they said, because there was only one Vietnam. We were given some food, and the talk went on and on into the small hours of the morning. When we started to nod, we were told that it wasn’t every day we got to talk to a high official and that we should stay awake. But it did begin to feel like Scheherazade working on her 900th tale.

For Kissinger and Nixon, the peace accords had awarded them peace with honor, or so they thought. But, as I wrote for the Washington Post at the time: “To the PRG of Long My it seemed that peace with honor meant nothing less than the completion of the Vietnamese revolution started so long ago by Ho Chi Minh, and that the American withdrawal and the cease-fire agreement were significant victories, but by no means the last step along that road.” That last step was not far off.

The Fall of Saigon

In the spring of 1975, on orders from the Washington Post, I went back to Saigon from Phnom Penh, where I had been for many weeks, just before that city fell to the implacable Khmer Rouge. South Vietnam appeared to be collapsing, and that was a bigger story in the eyes of the Post. The entire American enterprise in Indochina was falling apart with a speed no one had anticipated.

Thieu, without telling his American allies, had decided on a military evacuation of the Central Highlands to consolidate his forces. The evacuation was ill-planned and ended in panic and rout. Hue, Da Nang, Nha Trang and all the coastal cities were falling as South Vietnam’s once-proud army simply disintegrated.

I quoted President Gerald Ford as having recently said that “the will of the South Vietnamese people to fight for their freedom is best evidenced by the fact that they are fleeing the North Vietnamese.”

“The opposite appears to be true,” I wrote. “All over the northern part of the country the will to fight vanished when the panic struck, and some of the South Vietnamese army’s best units dissolved without firing a shot.

When discipline was gone some of the soldiers vented their rage and frustration by looting and killing people, and many of the refugees speak with contempt and hatred about the venality and corruption of the Saigon government. Many central Vietnamese hate the Saigon government.”

Thieu was finally persuaded to step down and flew away into exile, as the Americans tried to find a figure more acceptable to the Communists. But the Communists were having none of it.

As North Vietnamese forces drew closer, strangers would clutch at foreigners in the streets of Saigon begging to be rescued. Vietnamese friends I had known for years would come with drawn faces to plead for help. It was hard to look into their eyes and not see an accusation of betrayal.

As daylight broke on April 29, 1975, several of us went across the street and up to the roof of the Caravelle Hotel. With sinking stomachs we watched the lazy arc of a heat-seeking missile rise up and find its way to an airplane, which immediately disintegrated. We knew that very few of us would leave the city alive if the North Vietnamese decided to oppose the American air evacuation that was about to begin.

Years later the North Vietnamese commander, General Van Tien Dung, wrote that he had received instructions from Hanoi to press on with the attack on Saigon but not to interfere with an American evacuation—an order that he protested but obeyed.

At the embassy itself we found Marine guards furiously chopping down a tree in the courtyard behind the chancery in order to make room for a helicopter landing area. Ambassador Graham Martin had refused to let his staff cut it down before this moment, because he thought any sign that Americans might be abandoning Saigon would sow panic among the Vietnamese.

As morning turned to afternoon, the panic that Martin had feared came down upon us like a squall line. Hundreds of Vietnamese headed for the embassy, all beseeching to be let in. When the helicopters arrived from the South China Sea, the wash from their rotors tore open the plastic bags awaiting burning, and thousands of papers flew into the air in a confetti of secrets.

I got aboard a helicopter just as it was getting dark. In the South China Sea, an American fleet lay waiting below as well as flotillas of hopelessly overfilled boats packed with Vietnamese, like flotsam and jetsam left on the surface after a gigantic ship has gone down.

I jotted in my notebook a quote from a James Russell Lowell poem that is inscribed near the graves of British redcoats who fell at Concord bridge back in Massachusetts in that same month 200 years previously. “They came three thousand miles, and died, to keep the past upon the throne.” We had come 10,000 miles to Vietnam to do the same thing.

The evacuation went on through the night, the last being taken off the roof early in the morning the next day, when North Vietnamese tanks burst through the gates of Saigon’s presidential palace.

Returning to Saigon

Seven years later I returned to Saigon, now officially Ho Chi Minh City, although everyone still called it Saigon. I checked in to the Hotel Majestic, down by the waterfront. The last time I had seen it, there was a big hole in the facade where a rocket had hit during the ancient régime’s last days. Now, outside the front door, the abandoned legacy of America’s lost war, the mixed-race children left behind, begged for coins. Upstairs, when the door to my room closed behind me and the bellboy departed, to my surprise I found myself in tears.

As I made my rounds interviewing Saigon’s new masters, it became clear that Southerners in what had been the Viet Cong had been shoved aside by the Northerners and that everything was going to be done

Hanoi’s way.

Wrongheaded agricultural practices, abandoned in later years, were being imposed on Southern farmers. One also saw signs that Northerners were taking large quantities of luxury goods, fans, air conditioners, even refrigerators, away from Saigon to use in Hanoi and other Northern towns.

I spent Easter of 1982 in Hanoi, the first time I had been in the North. The city was run-down, with nothing for sale in the shops and depressed-looking people. But the old French colonial architecture was a delight. The Vietnamese today are tearing it down to make room for the new, but I would still rate Hanoi as the most charming city in Southeast Asia.

Easter Sunday dawned to a steady drizzle, but the Catholic cathedral was full to overflowing. I had expected religion to be suppressed, but clearly the Communist regime had decided not to be too strict in their official atheism.

The Russians were everywhere, and despite all they had done to help Hanoi during the war, they were not popular. When walking through the streets, children would shout “Russian, Russian.” One kid threw a bag of excrement at me.

My last trip to Vietnam, in 2000, revealed a country trying on the garments of capitalism while still keeping political control, much as China had done. Saigon was on its way to becoming a miniature Hong Kong with buildings sprouting and growing ever higher.

Like all American visitors, I was surprised by the lack of bitterness. I got a good explanation of that when I met with Vietnamese officials, who were quick to say that it was important for Vietnam to have normal relations with the world’s leading power, especially with a growling China next door. “And it helps to have won,” said a veteran of that long war.

The Revisionists

In the years since the fall of Saigon, revisionist theories have sprung up like weeds. It was said that we had actually won the war by 1972, that the South Vietnamese could have held on after our troops had left if only Congress had not closed down the war and refused to allow the United States to retaliate when the North Vietnamese broke everything agreed upon in Paris. But the South Vietnamese leadership was never able to instill a sense of dedication and sacrifice for their cause. The Communists represented nationalism, while the South always appeared to be the puppet of foreigners, and steeped in corruption at that.

I had seen the South Vietnamese hold the My Chanh line against Communist attack in the Easter Offensive of 1972, with the help of American firepower but not American ground troops. Revisionists have used this battle to say that if only we had supported the South in 1975, Saigon wouldn’t have lost the war. I do not buy that argument. Once the Paris Peace Accords allowed the North Vietnamese to remain in the Central Highlands, outflanking the South Vietnamese, the country’s fate was sealed. Besides, no matter how many times the North Vietnamese were halted, they always had the option to go home, lick their wounds and prepare for yet another offensive.

Many years after the war, I met former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, who had just written a book admitting that he and the Kennedy and Johnson administrations had been all wrong about the war. He said he had never understood that the war was more about Vietnamese nationalism than it was about communism. He and a team of Americans journeyed to Hanoi to talk to Vietnamese about how it had all seemed from their point of view. The Americans had believed that if they inflicted enough pain on the Vietnamese—bombed them and killed them in great numbers—there would come a time when they would throw in the towel. When McNamara brought this up with his Vietnamese interlocutors, they told him, to the contrary, the bombing had actually increased morale.

No strategy or tactic short of genocide, McNamara concluded, would have won the war for us. In Vietnam it was the other side who, in President John F. Kennedy’s words, were willing to pay any price, bear any burden, in defense of what they considered most important: the reunification of their country and the expulsion of foreign armies.

First published in Vietnam Magazine’s August 2016 issue.