A long with Anthony McAuliffe’s defiant exclamation at Bastogne, “Nuts!” and Douglas MacArthur’s promise, “I shall return,” one of the most famous phrases uttered by a soldier is Calvin Pearl Titus’ “I’ll try, Sir!” when he volunteered to scale the high wall surrounding the Chinese imperial city of Peking (today Beijing) on Aug. 14, 1900. The words epitomize the “can-do” attitude expected of American soldiers. The story behind it—which resulted in Titus being awarded the Medal of Honor by President Theodore Roosevelt—is worth telling, for it proves that the proverb “fortune favors the bold” can be very true.

In June 1900, Titus and his fellow 14th Infantry Regiment soldiers were in China because the secret “Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists” had attacked foreigners and foreign property with the goal of eradicating all foreign influences in China. Since many of the secret society members were skilled in martial arts or “Chinese boxing,” English-speakers began calling them “Boxers.”

The Boxers were convinced that economic hardship, recent floods, and droughts had been caused by foreigners in their midst. They detested the arrogance and aggression of foreigners, as well as their dismantling of China: the British had taken north Burma and Kowloon; the Japanese had seized Korea and Formosa (Taiwan); and the French had occupied Indochina’s Tonkin and Annan. The Germans had mining rights and the French had railroad concessions. While the United States denounced imperialism, America’s so-called “Open Door” policy was really more of the same—more foreign businesses and businessmen. The Boxers resented Christian missionaries and privileges they enjoyed; they also hated Chinese converts.

The Boxer Rebellion

Starting in 1899, the Boxers and their sympathizers began attacking foreigners in China, slaughtering scores of missionaries and Chinese Christians. They tore up railroad tracks, cut telegraph lines and murdered foreign engineers. The Qing dynasty government made half-hearted attempts to stop the Boxers but secretly many in the government were pleased by these attacks. Soon all foreigners were in grave danger, especially those living in Beijing. In June 1900, after convincing themselves that their martial arts rituals made them invulnerable to bullets, the Boxers arrived in Beijing and began attacking the Western businessmen and diplomats, and their families living there.

The United States, joined by Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Russia, sent troops to protect their citizens. On June 10, 1900, a multinational relief force of some 2,100 commanded by British Royal Navy Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour tried to reach Beijing from Tianjin, 70 miles away but was forced to retreat when Chinese imperial troops joined the Boxers in attacking his troops.

Things got worse on June 20 when Qing dynasty ruler Empress Dowager Cixi ordered all foreigners to leave Beijing for Tianjin. When the German minister went to discuss this order with Cixi, he was murdered. About 3,500 foreigners and Chinese Christians, afraid that they also would be killed, sought safety in that area of Beijing by international forces called the Legation Quarter. While about 400 soldiers of various nationalities set up a defensive perimeter, they were outnumbered by thousands of Boxers. When Empress Cixi learned that the foreigners in Beijing were refusing to obey her order, she decided to back the Boxers in their rebellion and declared war on all foreign powers on June 21. Fortunately for those in the Legation Quarter, the siege by the Boxers and imperial troops was disorganized, half-hearted and poorly led.

The United States deployed the 9th Infantry Regiment and a Marine battalion to Taku on July 7. Two battalions of the 9th took part in the assault on Tianjin, which surrendered on July 13. On Aug. 4, an allied expedition of about 19,000 men left Tianjin for Beijing. The U.S. force, under the command of Army Maj. Gen. Adna R. Chafee (future US Army Chief of Staff), consisted of the 9th and 14th Infantry Regiments, elements of the 6th Cavalry, the 5th Artillery and a Marine battalion. Since the siege of the Legation Quarter continued, the United States—along with Great Britain, France, Japan and Russia—organized a Relief Expedition of 55,000 men. On Aug. 14, 1900, the Americans were in Beijing. Facing them was a very tall wall which blocked entry into the “Forbidden City”—so called because common people, including foreigners, were prohibited from entering it. The Forbidden City had been the home of the Chinese emperors and their families for nearly 500 years.

A Musician To The Rescue

Musician (Pvt.) Calvin P. Titus, a bugler with Company E, 14th Infantry, was in the very small first group of Americans to reach the Tung-Pien Gate in Beijing’s eastern outer wall. It was 7:00 a.m. The soldiers included Col. Aaron S. Daggett, a tough and experienced soldier who had fought in the Civil War; First Lt. Joe Gohn, a company commander, Second Lt. Hanson, and Titus himself. The Americans immediately came under fire from the top of the ancient 30-foot wall and adjacent Fox Tower.

Recognizing that scaling the wall would be the best way to lay down suppressive fire and counter the enemy’s fire, Daggett mused out loud: “I wonder if we can get up there.” Titus remembered what happened next: “Well, I was just standing there. The bugler was always up front with his company commander.” Daggett knew Titus because he had been his bugler and orderly on more than one occasion at Daggett’s headquarters in Manila. Titus said to Daggett, “I’ll try, sir, and see if we can get up, if you want me to.”

Titus later remembered: “The Old Man [Daggett] just stood there, and sized me up from head to foot, and said ‘All right, if you think you can do it.’ I was a good climber, so up I went.” Titus took off his canteen, pistol belt, hat, and haversack. The wall was “made of brick…mortar had fallen out in places making it possible for me to get fingers and toeholds in the cracks.” About halfway up, a bush growing from the bricks gave Titus something better to hold on to.

Climbing Into the Forbidden City

Titus managed to reach the top of the wall and looked through the firing ports on the top of the wall. No one was there. He slid over the top of the wall and dropped down to the floor behind it. Following the trail just blazed by Titus, more soldiers followed him to the top—climbing unarmed as he had done. The men then hoisted their weapons and ammunition to the top of the wall by tying their rifle slings together in a rope.

Daggett later described watching Titus make the treacherous climb. “With what interest did the officers and men watch every step as he placed his feet carefully in the cavities and clung with his fingers to the projecting bricks! The first 15 feet were passed over without serious difficulty, but there was a space of 15 feet above him. Slowly he reaches the 20-foot point. Still more carefully does he try his hold on those bricks to see if they are firm. His feet are now 25 feet from the ground. His head is near the bottom of the embrasure. All below is breathless silence. The strain is intense. Will that embrasure blaze with fire as he attempts to enter it? Or will the butts of rifles crush his skull? Cautiously, he looks through and sees and hears nothing. He enters, and as good fortune would have it, no Chinese are there.”

Titus’s willingness to climb the wall—unarmed and without knowing what might face him at the top—inspired those around him. The American flag was soon flying atop the wall for all to see. This opened the way for British troops to relieve the Legation Quarter. The following day, 5th U.S. Artillery pounded the gates of the Inner City. Empress Cixi fled the city. Following negotiations, the Boxer Protocol was signed Sept. 7, 1901, ending hostilities and mandating reparations to all Allied powers. The Qing dynasty, now very much in decline, lasted another 10 years before it was overthrown in 1912.

Medal of Honor

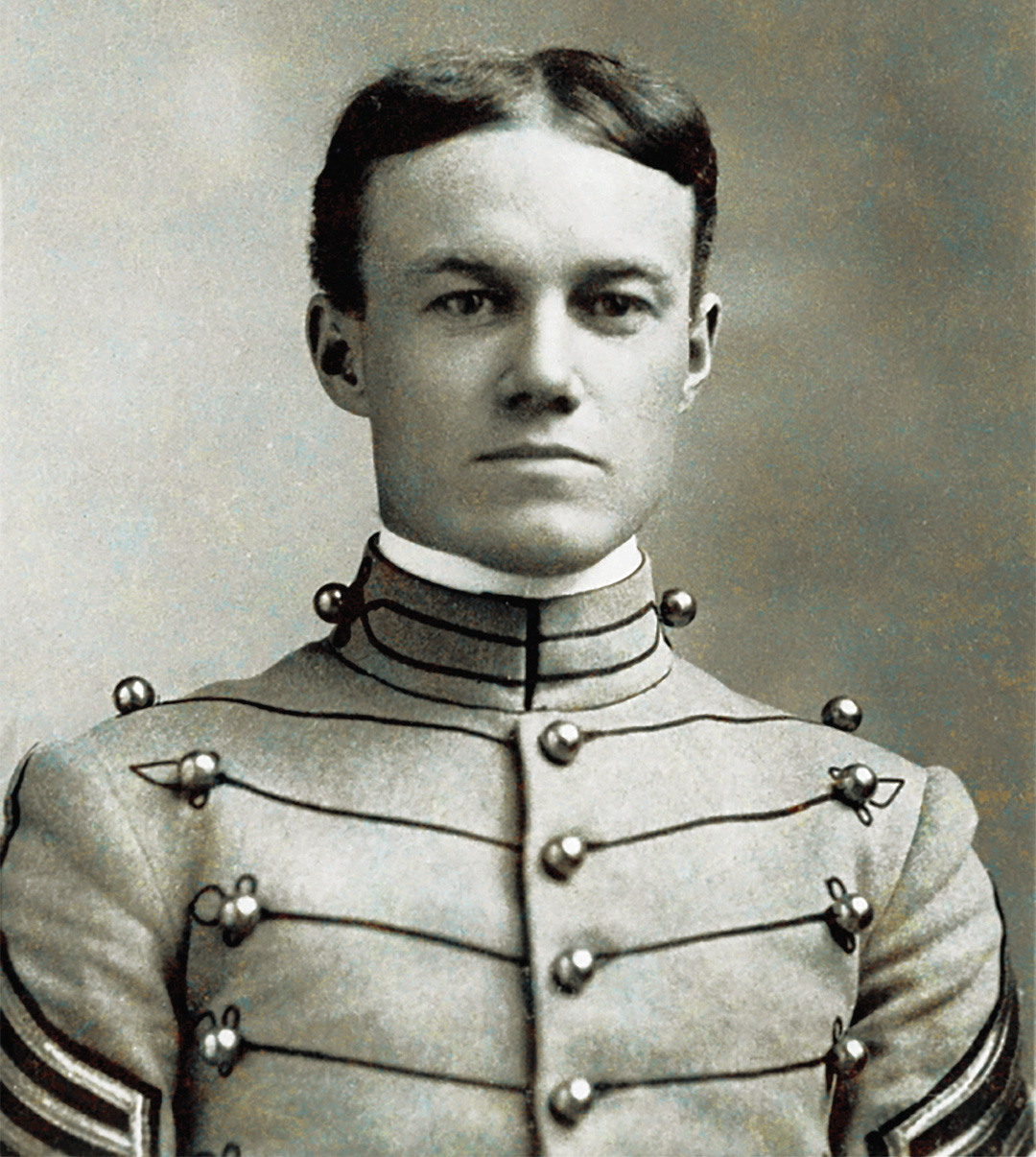

Titus’s fearlessness earned him an “at large” appointment to the U.S. Military Academy in 1901, where as a “Plebe” (first-year cadet), he was presented the Medal of Honor by President Theodore Roosevelt during West Point’s centennial celebration in spring 1902. It was a unique event; no cadet had been awarded America’s highest military award, and no other has to this day. The cadets were drawn up in front of the President’s flag. Roosevelt, accompanied by Lt. Gen. Nelson A. Miles (also a Medal of Honor recipient), walked on both sides of the line to inspect the Corps. The adjutant ordered Titus to step to the front, then read his citation, which was, as typical in that era, quite simple. It said only that he was being awarded the medal “for gallant and daring conduct in the presence of his colonel and other officers and enlisted men of his regiment; was first to scale the wall of the city.”

According to an article in the Army and Navy Journal, Roosevelt then advanced, bearing the medal. He then pinned it on Titus’ coat and shook his hand with great cordiality. “Now, don’t let this give you the big head!” Roosevelt reportedly said to Titus. After the ceremony, a third-year cadet named Douglas MacArthur approached Titus, looked at his medal and commented, “Mister, that’s something!” MacArthur had seen the decoration previously, since his father Lt. Gen. Arthur MacArthur Jr. had been awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism as a lieutenant during the 1863 Civil War Battle of Missionary Ridge. MacArthur would receive his Medal of Honor some 40 years in the future.

Graduating in 1905, Titus returned to the 14th Infantry in the Philippines as a second lieutenant. From August 1916 to February 1917, then Capt. Titus served with the 24th Infantry Regiment in Gen. John J. Pershing’s Punitive Expedition into Mexico. He subsequently was on the Mexican Border Patrol with his unit in New Mexico.

World Wars I and II

During World War I, Maj. Titus commanded a battalion in the 24th Infantry in Columbus, New Mexico until he attended the Army War College in Washington, D.C. He then deployed to Germany where he commanded the 16th Infantry in the Army of Occupation. Lt. Col. Titus also taught Reserve Officer Training Corps cadets at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He retired from active duty in 1930.

On Dec. 13, 1941, days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Titus asked he be recalled to active duty. In a letter to the commanding general at the Presidio of San Francisco, he asked if there was “some staff or desk job that I could hold down! It is true,” he wrote, “that I have been completely away from Army stuff for years but I . . . can still think straight and make decisions.”

The Army declined his request, but his letter showed that his “can do” spirit still was a part of his character. Sometime after scaling the wall on Aug. 14, 1900, Calvin Titus had been wounded in the neck by a shell fragment. It was not a serious injury but it was not forgotten: the Army awarded then retired Lt. Col. Titus the Purple Heart in 1956—more than a half century after he was wounded in combat.

Titus died at a Veterans Hospital in Sylmar, Ca. on May 27, 1966 at 86. The Army commissioned an H. Charles McBarron painting of the scene at the Chinese wall, which featured in the popular “The U.S. Army In Action” series of posters. Titus’s famous “I’ll Try, Sir!” is the official motto of the 5th U.S. Infantry Regiment. In 1995, the Military Sealift Command renamed a Logistics Prepositioning Ship (AK-5089) Lieutenant Colonel Calvin P. Titus. While no longer afloat, it was used to carry cargo to U.S. military units around the globe.