Born in Missouri in 1864, he left St. Louis after his 16th birthday to become a cowboy, winding up in Montana’s Judith Basin where he cowboyed, sketched and painted.

As the C.M. Russell Museum’s Chan and Clara Ferguson Chief Curator, Sara Burt is surrounded by many of Charlie Russell’s Western masterpieces, including The Jerk Line (1912), The Exalted Ruler (1912) and The Fireboat (1918). But ask her to select her favorite piece in the Great Falls, Montana, museum, and she doesn’t have to think long.

“We have on long-term loan from one of our board members a set of eight watercolors done in 1919 illustrating a book called Indian Old Man Stories by Frank Linderman,” Burt says. “These are Native American origin stories and how-come and why stories gathered by Linderman, a writer in Montana and Charlie’s contemporary, and he was very much an advocate of Indian causes and cultures, as was Russell. So the two of them interviewed one of the elders of the Blackfeet, Cree and Chippewa tribes, and Frank gathered these oral stories and set them down and asked Charlie to illustrate them. We have the original eight illustrations for this book, and I think they’re quite stunning. I had no idea Russell did things like that.”

Russell did a lot of things in his life. Born in Missouri in 1864, he left St. Louis after his 16th birthday to become a cowboy, winding up in Montana’s Judith Basin where he cowboyed, sketched and painted. He also loved the Indian life, and spent the summer of 1888 in Alberta visiting Blood Indians. He was a conservationist, outdoorsman, writer, environmentalist, historian, but mostly an artist, completing almost 4,000 works before his death in Great Falls in 1926.

His works are spread across the country, in various museums and private collections, but there’s no better place to learn about Russell that at the C.M. Russell Museum, which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year. After all, Russell did most of his masterpieces inside his Great Falls studio.

That studio, made of red cedar telephone poles and completed in 1903, is on the museum grounds. So is Russell’s two-story home, built three years earlier. The museum itself features not only Russell’s art, but the comprehensive “The Bison: American Icon, Heart of Plains Indian Culture,” which chronicles the history and importance of the bison; collections of artists Olaf C. Seltzer and Gary Schildt; “The Browning Firearms Collection;” a research library; a hands-on children’s center; and gift shop.

To celebrate the museum’s 60th anniversary, the special exhibit “I Beat You To It”: Charles Russell at the Mint runs through September 14. A friend of Russell and collector of his art, Sid Wallis owned 10 oils, 25 watercolors, 17 illustrated letters and a set of Russell’s wax models, which he proudly displayed in his Mint saloon in Great Falls from the late 1890s to 1945.

“After prohibition in 1919, he turned it into a lunch counter and soda parlor, but the biggest attraction was coming to see the Russell collection,” Burt says. “It operated as sort of a private museum, attracted people from all over the country and even foreign visitors.”

When Wallis finally sold the Mint, he asked that the art collection remain in Montana, but funds couldn’t be raised. Eventually, the work wound up owned by Fort Worth, Texas, collector Amon Carter.

“Montana felt it was the one that got away,” Burt says.

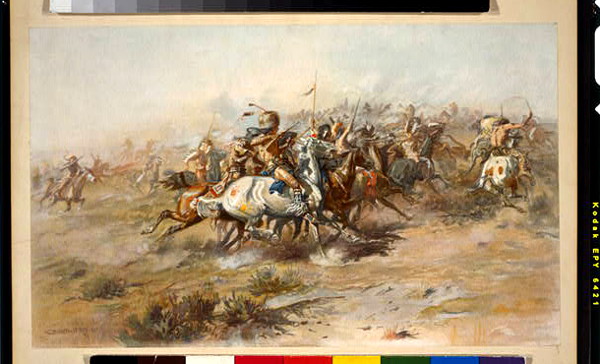

Now, seven of the major pieces from Wallis’s collection, including The Hold Up (1899) and Buffalo Hunt No. 26 (1899) and other memorabilia—such as Russell’s illustration that became the Mint’s logo and slogan: “Don’t Let Anyone Beat You To It”—are back in Montana. Also borrowed from the Montana Historical Society is Russell’s last watercolor, When Cows Were Wild.

Why does Russell’s work endure?

“He is very funny, overtly but also covertly,” Burt says. “He’s pretty sophisticated in his humor when you start looking at him. and I think that continues to engage people. They love the stories, but they also love to get the humor that he has often imbedded, and I find that fascinating.

“His work is accessible. It’s not hard to understand. Over time he becomes quite a brilliant draftsman and colorist and probably from 1880s through the rest of his life he has an element of romance and nostalgia that people who love the West are very drawn to.”

Nancy Plain, who won a Spur Award in 2008 for her juvenile biography Sagebrush and Paintbrush: The Story of Charlie Russell, The Cowboy Artist, agrees.

“The Wild West might not be as wild anymore, but the land is still there,” Plain says. “And the old stories of cowboys and Indians live on in memory and imagination. The cowboy artist’s work is timeless.”

Russell’s art remains on an upward swing, Burt says, as far as status, collectibility and prices.

“When I started working as an art historian 20 years ago, my field did not embrace Western art,” she says. “It was considered a lesser form of art, but now it’s considered as important as any other contribution to the history of American art. Russell has taken a place as one of the icons, side by side with [Frederic] Remington, and some say he’s better than Remington. Remington was a great painter, but there’s probably more substance to Charlie.

“He is really and truly an incredible storyteller. The more I work, the more I see his work, the more I’m impressed with his ability to tell a story visually.”

For more information, log on to www.cmrussell.org.