A reformed sinner’s annotated Bible kicked off Protestant fundamentalism

CAMEO

BY AGE 36, Cyrus Ingerson Scofield had failed magnificently. Accused of forgery and embezzlement, he had slipped into an alcohol-soaked despair. In 1879, he quit drinking, embraced Jesus Christ, and devoted himself to evangelism—spreading the word about the importance of personal salvation and biblical authority. Three decades later, he created the Scofield Reference Bible, sometimes cited as a plinth of Protestant fundamentalism. Conforming to a theological view known as pre-millennial dispensationalism, Scofield’s Bible presents history as epochs governed by divine covenants. In the last epochs, for example, to fulfill God’s plan, Jews must return to the Holy Land. Some scholars cite the Scofield Bible as a factor that helped forged longstanding support among American evangelicals for the nation of Israel.

Scofield’s life began in trauma: his mother died delivering him in 1843 in Tecumseh, Michigan. He was raised by his father and stepmother,

and when she too died, he moved at age 16 to Lebanon, Tennessee, to join his older sisters. When the Civil War came, he enlisted in the Confederate Army, serving at Seven Pines and Antietam. He married a Catholic and in St. Louis went to work for her wealthy fur-trading family, acquiring legal skills. The couple had two children, and by 1869 Scofield was working in Atchison, Kansas. In 1871 he was elected to the Kansas legislature. In 1873, President Ulysses S. Grant named him U.S. attorney general of the District of Kansas, but within six months political intrigue regarding vote buying forced his resignation. In 1878, he was jailed on charges of check forgery.

Battling the bottle, Scofield left Atchison for St. Louis, where clergymen took him in hand, support that led in 1880 to a local preaching license. In 1882 his sermonizing and outreach won him a chance as a pastor at the First Congregational Church in Dallas, Texas. In 1883, he and his long-estranged wife divorced. Scofield never mentioned that “mixed” marriage to his new community, and later excluded his two daughters from that union in his will. In 1884 he married a congregant. He built First Congregational’s enrollment from 12 to 500 members.

In 1886, Dwight Moody, an enterprising evangelist and publisher, invited Scofield to address a biblical conference in Northfield, Massachusetts. The focus was a return to basics: the authority of Scripture, acceptance of Jesus Christ as savior, and the inevitability of a period of earthly tribulation preceding the Second Coming.

This orientation and its promise of unwavering truth resonated in the Civil War’s aftermath, with its social, political, and economic upheavals. Modernity—along with the spread of evolutionary theory presented by English naturalist Charles Darwin—was shaking pillars of traditional authority. Reacting to historiographical and scientific trends that undercut the notion of the Bible as God’s unerring word, mainstream Protestant denominations had begun to read the Gospels in a forward-looking way, positing that devotion to Christ’s teachings leads to a better, more just world. Scofield and colleagues promoted a simpler view. Rather than read the Bible through the lens of historical events, they applied the lens of Scripture to history, biblically dividing all of history into seven epochs. “The past is seen to fall into periods,” he wrote. “The clear perception of this doctrine of the Ages…has the same relation to the right understanding of the Scriptures that correct outline work has to map making.”

Premillennial dispensationalists such as Scofield forecast a period of tribulation and a millennium when Jesus Christ returned to earth before the final judgment. A dispensation is “a period of time during which man is tested in respect of obedience to some specific revelation of the will of God,” he said. Of seven dispensations in the biblical construct, the sixth outlined Jews’ return to Israel. The seventh and final dispensation governed the unfolding of the millennium and the end of time. Scofield also highlighted the concept of the Rapture, the ascent to heaven by Christian believers, in his notes about Thessalonians 4:17.

Feeling End Times—the storied period of tribulation—were near, Scofield wanted to save others. Regarding the Bible as a manual for

interpreting experience, he collected notes about biblical text, in 1888 producing Rightly Divided the Word of Truth—the title is from II Timothy 2:15—explaining how biblical prophecies foretell history and salvation. The booklet helped readers interpret Scripture on their own, eliminating the need for expertise. Disciples, not denominations, was Scofield’s goal, along with immediate individual salvation rather than church building.

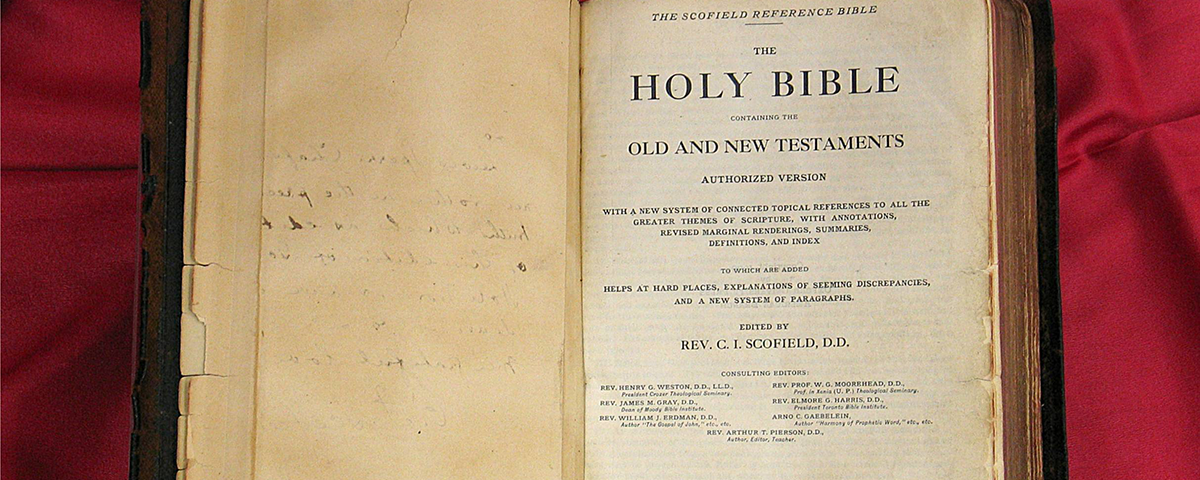

In 1890 Scofield established the Central American Mission and in 1895 a correspondence Bible course enrolling 10,000 students intent on becoming pastors. By 1905 he had resigned from his congregation to work on a reference Bible. With eight consulting scholars, he created the first study Bible with title headings, explanations on each page, and a novel system of references. Scofield borrowed chronologies from 17th century Irish archbishop James Ussher. The book of Genesis, for example, is said to span 2,315 years; Deuteronomy, 40. In 1909 Oxford University Press published the work, advertised as “a new system of connected topical references [in which] all the greater truths of the divine revelation are so traced through the entire Bible, from the place of first mention to the last, that the reader may for himself follow the gradual unfolding of these.”

In 1913 Scofield helped found the Philadelphia School of the Bible, now Cairn University. Philanthropist Charles Huston of Lukens Steel underwrote the project. The next year came World War I—the Great Tribulation, some said. Three years and 40 million casualties later, on December 30, 1917, in British General Edmund Allenby’s conquest of Palestine, devout dispensationalists saw a portent of the prophesied return of Jews to Israel. “Now for the first time, we have a real prophetic sign,” Scofield wrote to a friend.

However, no Rapture ensued. Peace undermined the End Times message, creating an opening for Indiana Baptist and noted anti-evolutionist William Bell Riley, who argued ardently in 1918 for a more organized evangelical approach. Riley deemphasized the End Times and stressed nurturing Christian communities through missionary work and church building.

Scofield opposed such centralization. Historian Richard Kent Evan says that Riley’s 1919 break with Scofield on this point and Riley’s establishment of the World Conference on Christian Fundamentals birthed establishment fundamentalism in the United States.

Scofield’s death in 1921 did not end the vogue for reading current events biblically. For some, Israel’s 1948 founding echoed prophecy. In 1967 a team lightly revised the Scofield Bible; that year, in another seeming alignment with prophecy, Israel won a war with Arab neighbors. Since then evangelical Christians have enthusiastically supported American politicians backing Israel. A 2018 survey of white evangelicals showed that 71 percent supported Donald Trump, whose administration’s 2018 decision to move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem further broadcasts an American tie to the Jews’ Holy City.

Selling tens of millions of copies, the Scofield Bible remains popular, thanks in part, scholar Brendan Pietsch says, to worldly touches by Oxford’s publisher, Henry Frowde. The Scofield Reference Bible was only one product of a vibrant enterprise that printed Bibles on Oxford India paper—lightweight, sturdy sheets of cotton and hemp since replaced by other acid-free papers.

Cyrus Scofield is not a household name, but his End Times theory resonates with American evangelicals. Friend and disciple Lewis Sperry Chafer founded and ran Dallas Theological Seminary 1924-52. In 1970 a student of Chafer’s, Hal Lindsey, wrote Late Great Planet Earth, a best-seller about the End Times, fictionalized in a 1979 movie. A 1995 Rapture-centered novel by evangelical pastor Timothy LaHaye begat the 2014 movie Left Behind. These works use popular forms to portray the End Times, but Scofield noted scripture’s ambiguity on the issue. Of the Book of Revelation, he wrote, “Doubtless much of which is designedly obscure to us will be clear to those for whom it is written as the time approaches.”