No one studied the English naval expert’s strategic blueprint more closely than a Japanese officer named Isoroku Yamamoto–the architect of Pearl Harbor.

Hector C. Bywater–a convivial, pub-crawling English journalist, author, and raconteur who in the 1920s and 1930s knew more about the world’s navies than a roomful of admirals–had an obsession: the possibility of war between Japan and the United States.

By 1925, 16 years before Japanese forces struck at Pearl Harbor, he had accurately predicted the general course of the Pacific War. The fulfillment of his prophecies was no mere accident: What he wrote powerfully influenced Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander in chief of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Navy, and a host of leaders of the U.S. Navy as well.

Bywater imagined that Japan would make a surprise attack against the American naval presence in the Pacific and launch simultaneous invasions of Guam and the Philippines. By taking such bold steps, Bywater calculated, Japan could build a nearly invulnerable empire in the western Pacific. He also surmised that, given time, the United States would counterattack. Immense distances would separate the adversaries after the fall of Guam and the Philippines, but ultimately, Bywater believed, the United States would be able to reach Japan by pursuing a novel campaign of amphibious island-hopping across the central Pacific. The result, he said, would be “ruinous” for the aggressor. With that outcome in mind, he advanced his ideas in the hope of deterring Japan from attempting any such adventure.

Bywater’s two books and many articles on Pacific strategy attracted brief notice from the public and were soon forgotten. But for professional navy men on both sides of the Pacific, his work became required reading. Indeed, Bywater succeeded Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan as the world’s leading authority on naval theory and practice.

Until now, historians believed that Admiral Yamamoto, architect of the Pearl Harbor strike and many of Japan’s subsequent moves in the war, conceived his war plans independently. But today it can be shown that Yamamoto, while serving as naval attaché in Washington in the late 1920s, reported to Tokyo about Bywater’s war plan and then lectured on the subject, adopting Bywater’s ideas as his own. Yamamoto followed Bywater’s plans so assiduously in both overall strategy and specific tactics at Pearl Harbor, Guam, the Philippines, and even the Battle of Midway that it is no exaggeration to call Hector Bywater the man who “invented” the Pacific war.

Bywater’s influence on the U.S. Navy was such that many officers at the highest level considered him “a prophet.” He was the first analyst to publicly spell out the revolutionary concept of island-hopping across the Marshall and Caroline chains, a concept that became a fundamental of American strategy during the war. A year and a half after Bywater published this proposal, the navy drastically revised its top-secret War Plan Orange—the official contingency plan for war against Japan. The option of a reckless lunge across the Pacific, which Bywater said was doomed to failure, was replaced with his careful, step-by-step advance.

Bywater was a man of mystery and paradox. A tall, imposing figure, he could hold the rapt attention of a packed pub room when he recited poetry, sang, or told anecdotes, such as the one about how he mischievously persuaded Mussolini to invest a fortune in modernizing a couple of old rust buckets. But Bywater also had a hidden side: Between 1908 and 1918 he lived the double life of a spy—first as a British Secret Service agent and later as a naval intelligence agent. He deceived not only the Germans, from whom he extracted a bounty of naval secrets, but also his friends and neighbors in Britain and the United States.

He was nothing if not quintessentially British—coolly precise, wry, and steel-nerved. He used to say he was drawn to the navy by the accidents of his surname and his birthday—Trafalgar Day. Although he was renowned for his penetrating intellect and unaffected by the illusions that blinded so many in his generation, his private life was storm-tossed by emotion. He angrily resigned from the two daily newspapers he worked for the longest, the Baltimore Sun and the London Daily Telegraph; fought with and divorced two wives; excoriated the British Admiralty; and once indignantly rejected one of his country’s highest decorations—the Order of the British Empire.

In the last analysis, however, one marvels at his daring, dazzling mastery of all things naval and at his remarkable but as yet unacknowledged influence on the history of our time.

IN THE YEARS AFTER WORLD WAR I, Bywater’s imagination was captured by the naval rivalry developing in the Pacific between Japan and the United States. He began to write a series of articles on the subject for such publications as the British Naval & Military Record and Royal Dockyards Gazette. He soon expanded these ideas into a book, Sea Power in the Pacific, which was published in 1921—just in time to become a major topic of discussion at the International Conference on Naval Limitation, which convened in Washington later that year. Bywater covered it as a correspondent for the Sun.

Bywater was not the first Western thinker to focus on the strategic importance of the Pacific Ocean; nor was he alone in imagining that diminutive Japan might overcome the United States in a future Pacific war. In 1909, Homer Lea’s Valor of Ignorance had gone so far as to forecast Japan’s domination of the Pacific and capture of California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. Lea’s book was followed by a score of imitations by American and Japanese authors. In 1911, even Mahan, while dismissing Homer Lea’s nightmare vision as “improbable,” observed that it was not inconceivable that the new Japanese navy might one day defeat the American navy in the Pacific.

What was new and different about Hector Bywater’s analysis was, first, his clear-sighted recognition of exactly how far Japan could go in a war against the United States. Japan, he understood, could snatch U.S. territories in the western Pacific and thereby build a nearly unassailable ring of insular territories around herself, yet she did not have it within her power to seize Hawaii, let alone seriously menace the continental United States.

Second, he foresaw that such an aggressive move by Japan might well be in the cards, so to speak. He was the first journalist of his generation to grasp that the central arena in the struggle for naval supremacy had shifted from the North Sea and the Mediterranean, where Great Britain and Germany had vied with each other since the turn of the century, to the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific, as he saw it, was no longer an exotic backwater or even merely the scene of a possible future war, but the fateful setting in which the victorious allies of the First World War would test each other to determine who should be mistress of the seas in the 20th century.

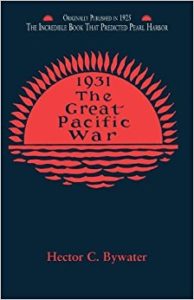

In 1924 Bywater realized that the treaties that had emerged from the Washington conference postponed but did not eliminate the possibility of war between the United States and Japan. So he started to work on a second book—a technically precise novel that played out the revolutionary ideas he had developed in Sea Power in the Pacific. He called this new book, published in 1925, The Great Pacific War.

In 1924 Bywater realized that the treaties that had emerged from the Washington conference postponed but did not eliminate the possibility of war between the United States and Japan. So he started to work on a second book—a technically precise novel that played out the revolutionary ideas he had developed in Sea Power in the Pacific. He called this new book, published in 1925, The Great Pacific War.

Bywater had no desire to stir up enmity between Japan and the United States; a war between the two powers would be “a terrible and protracted struggle,” he wrote in the preface. His object was “to bring to light certain facts concerning the strategical situation of the rival Powers the full significance of which does not appear to be realized either in Japan or the United States.” Accordingly, he stated, “such modest influence” as his book might exert would be “in the direction of peace rather than of war.”

The first question Bywater had to answer in writing The Great Pacific War was: What would prompt the fighting to begin? From his reading of Japanese history and current affairs, he had come to believe that the military caste in Japan would rise to power. Thus, he imagined that a group of “military chiefs” might gain control of the Japanese government. They then adopt a policy “aimed at the virtual enslavement of China,” he wrote, and very quickly find themselves on a collision course with the United States. Diplomatic notes are exchanged—”bellicose” and “truculent” dispatches from the Japanese, “courteously worded” ones from the Americans, who are “determined to prevent the catastrophe of war.” Amid these negotiations, Japan launches a surprise attack, rendering her declaration of war a few days later “a somewhat superfluous formality.”

Such a surprise attack was by no means unprecedented. In 1904, prior to a declaration of war, a dozen Japanese torpedo boats had assaulted czarist Russia’s Asiatic squadron at Port Arthur, sinking three capital ships. But at Port Arthur, Japan had risked no major units of the Imperial Navy and sought only the limited goal of throwing the enemy off-balance. In contrast, Bywater imagined that the Japanese commander would assemble a major fleet of capital ships so as to hurl an “overwhelming” force at the U.S. fleet in the Philippines—the fleet was not stationed at Pearl Harbor until 1940—aiming for its “annihilation” during the first hours of the war.

Accordingly, he described the Japanese surprise-attack fleet as a force that would include an aircraft carrier, the battleships Hiei and Kirishima (both of which were in fact in the Pearl Harbor strike force in 1941), and numerous auxiliaries. Commanded by an imaginary Vice Admiral Hiraga, this armada steams south hoping to catch the Americans napping at their base at Manila Bay, just as George Dewey found the Spanish fleet there in 1898. But at the eleventh hour Rear Admiral Ribley, the imaginary commander in chief of the U.S. squadron, takes his ships to sea because, as he puts it, “we do not know if war has been declared, but…there is something in the air which tells us the fight is about to begin.”

IN BYWATER’S DRAMA, THE FIRST SHOTS COME from carrier-based aircraft. Japanese fighter-bombers are engaged by American planes, including a number from the aircraft carrier Curtiss (in fact, a seaplane tender Curtiss was in action at Pearl Harbor in 1941). But these skirmishes are indecisive, and soon the Americans spy on the horizon the pagodalike foremasts of Japanese men of-war bearing down on them. Shortly, Japanese heavy-caliber guns find the range of their targets. Bywater describes the devastating rain of bombs and shells in the words of a U.S. naval officer, a Lieutenant Elkins:

All around us the sea spouted and boiled; there were half a dozen terrific explosions in as many seconds;…then there was a blaze of light… and everything came to an end for me. When I recovered my senses. I was being dragged into a boat from the destroyer Hulbert. They told me the flagship had foundered at 11:30, having been practically blown to pieces. There were only six survivors besides myself. [Admiral Ribley] had gone down with the ship…

From our boat, we could see the Japanese sweeping up the remnants of our squadron. Shortly before the flagship went down, the Frederick had blown up with all hands. We could see the Denver lying over on her beam ends, on fire from stem to stem. Nearby was the Galveston in action with Japanese light cruisers, which were absolutely pumping shells into her. Even as we watched she put her bows deep under, the stern came up, and she took her last dive…

Concluding the narrative with a flash of seeming clairvoyance, Bywater has Lieutenant Elkins report: “Our squadron had been wiped out and upwards of 2,500 gallant comrades had fallen.” At Pearl Harbor in 1941, the precise number of American casualties was 2,638.

Bywater was not writing a novel of the usual kind. Instead, by precisely describing the geographic and topographical features of contested areas, and by using the exact names, tonnages, fuel ranges, and arms and armor specifications of real warships and aircraft, he was staging a complex war game. The result, he hoped, would point to the way a war in the Pacific would really work itself out.

The Japanese surprise attack comes like a “bolt from the blue” to the American people. The United States is swept by “a wave of grief…thinking of those thousands of gallant seamen who had gone to their doom, fighting to the last against tremendous odds, with the old flag still flying as the waters closed above the torn and battered hulls of their ships.” After the attack, the mood of the nation is not one of defeatism as the Japanese hope, but rather of “a stern resolve to see this struggle through to the bitter end.” Before the United States can respond to the destruction of its fleet, however, Japan follows up with simultaneous amphibious assaults against Guam and the Philippines. Although a highly publicized disaster at Gallipoli in World War I had given amphibious operations a bad name in the West, this was not the case in Japan. “Landings on supposed hostile coasts had been practiced year after year as a regular feature of Japanese Army maneuvers,” Bywater wrote. “All necessary equipment—boats, barges, pontoons, and portable jetties—had been in readiness at the military depots for years.”

With virtually all American warships destroyed, out of commission, or far away, the Japanese perceive that the chief danger would come from American aircraft. “Thirty machines of a new and powerful type,” Bywater stated, had just arrived in the Philippines from the United States. (The parallel with the arrival of 35 new B-17 Flying Fortresses in early December 1941 is remarkable.) He also assumed that the Japanese had studied the Philippines closely. “Every yard of ground had been personally surveyed and mapped by Japanese officers,” he wrote.

In the invasion plan, much of which would prove to be astonishingly prophetic, the Japanese first bombard Santa Cruz, on the west coast of Luzon, the principal island in the Philippines. This stratagem, however, is “so obviously a ruse to draw the Americans away from other parts of the coast that it failed in its purpose.” Next come air strikes. Japanese interceptors attack American patrol craft on the east coast of Luzon, and then bombers hit the airport at Dagupan, on Lingayen Gulf, aiming to destroy those 30 American craft “of a new and powerful type.”

Between dusk and the next morning, the main landings take place. They come in the shape of a three-pronged attack, simultaneously throwing ashore 40,000 troops at each of two sites on Luzon and another 50,000 at Sindangan Bay on Mindanao, the second-largest and southernmost of the major Philippine islands. Luzon is attacked from both east and west. On the west coast, Japanese troop transports assemble in Lingayen Gulf; their landing barges head for the gently sloping beaches that lead directly to the Pampanga Plain, which extends all the way to Manila.

On the east coast of Luzon, the transports make for Lamon Bay; here the terrain is mountainous, but the landing site is even closer to Manila. The western and eastern forces, equipped with tanks and heavy artillery, rapidly converge on the capital, obliging its defenders to divide their strength and fight on two fronts. Meanwhile, a Japanese expeditionary force overwhelms the garrisons at Zamboanga and Davao. In less than three weeks, Manila surrenders and the Philippines are in Japanese hands. So is Guam.

“A cordon had been established across every line of approach to the waters of the South-West Pacific,” Bywater wrote, explaining Japan’s formidable posture. “For a war with the United States, Japan’s strategical position very closely approached the ideal.”

This was a thesis Bywater had been propounding since his first articles on Pacific strategy in 1920, yet it was one that he doubted most U.S. authorities could accept. He knew that many top strategists believed the U.S. Navy could whip the Japanese navy regardless of the location of enemy bases and the length of American supply lines. To dramatize the foolhardiness of this belief, he described a reckless American stab at the Bonin Islands.

If successfully captured, a base so close to the Japanese home islands might lead to a speedy conclusion of the war. However, the Americans have underestimated the obstacles in their way. After suffering heavy losses, the U.S. fleet limps home ingloriously. There is a public outcry in the United States, followed by resignations in the high command of the navy. American leaders have now learned the hard way that the only practicable means of striking Japan is by hopping from island to island across the Pacific, carefully retrenching after each new conquest and pausing to bring up the rear.

The “guiding genius” of this island-hopping campaign, Bywater imagines, is an Admiral Joseph Harper, former commander of the U.S. garrison on Guam, who escapes from the island in a submarine—much as MacArthur would depart from the Philippines in 1942. Harper, whose knowledge of Pacific islands is extensive, plays the bluff-and-deception game craftily.

Bywater has Admiral Harper begin his campaign (as did U.S. forces in 1942) with noisy preparations in Alaska and the Aleutians to lure the Japanese to the North. But his real attack is aimed at the central Pacific— from Hawaii to Tutuila in American Samoa. He next makes a long thrust to Truk in the Carolines, deep inside the Japanese defensive perimeter. Just when it seems that U.S. forces might be cut off from their line of supply, he whirls around and makes simultaneous thrusts to Ponape, also in the Carolines, and to Jaluit in the Marshalls; this maneuver opens a direct, and much shorter, line of communication with Hawaii. Then comes a feint at Guam and a leap to Angaur in the Palaus, followed by a feint at Yap in the westernmost Carolines. The Battle of Yap—which Yamamoto aped in his plan for the historic Battle of Midway—is a turning point in Bywater’s war.

By this time, it is approximately a year and a half since the Japanese surprise attack that started the war. The Americans have managed to replace all naval losses, and, thanks to Admiral Harper’s brilliant tactics in the central Pacific, American warships in the vicinity of Yap are within striking distance of the Philippines—the final link in the chain of islands reaching across the Pacific toward Japan. The tables have turned: The U.S. Navy is now the superior force in the Pacific. At this point in the narrative, Bywater spelled out the American strategy for compelling Admiral Hiraga, the fictional Japanese commander in chief, to accept battle.

The commander of the American fleet, an imaginary Admiral Templeton, concentrates at his base a prodigious force: 17 aircraft carriers and battleships, numerous cruisers, destroyers, and other support ships. A vanguard of this force, including the battleship Florida, commences a bombardment of Yap while troop transports “so maneuver as if to suggest that a landing was about to be attempted.” The Japanese commander, Admiral Hiraga, has no choice but to employ every weapon at his disposal to block this advance—which, if successful, would carry U.S. forces to Japan’s door. The Japanese Grand Fleet (including a dozen battleships and aircraft carriers, 21 cruisers, and two immense destroyer flotillas) abandons its lair at Manila and strikes out for Yap.

First contact takes place when 50 torpedo planes from the carriers Lexington and Saratoga are met by an equal number of Japanese aircraft. After all of these planes—about a third of those available to either side—are brought down by “a hurricane of fire,” Bywater argues that a decision must then “be achieved by weapons other than the air arm.” Bywater goes on to describe a naval gunfight in the classic Jutland tradition.

Bywater’s belief that the big naval gun would remain the supreme weapon of war was his most serious lapse in an otherwise stunningly farsighted book. In 1925 he could not imagine the coming importance of air power. By the mid-1930s he sensed this defect in his forecasts; in subsequent editions of Sea Power in the Pacific and in articles, he declared that Japan’s opening stroke in the war would be delivered by her new aircraft carriers. For now, however, he remained—in this respect—a prisoner of his times.

Of course, Bywater did not foresee the atomic bomb. Yet he did sense that the United States might attempt something out of the ordinary to spare both sides the horror of an invasion of the Japanese homeland. This coup de grace, he guessed, would be a “demonstration” air raid over Tokyo with bombs containing not TNT but leaflets urging the Japanese to petition their government to surrender, rather than “waste more lives.”

Fictional characters always extricate themselves from predicaments better than real people do, and Bywater’s Japanese are no exception. After the demonstration raid has made its point, Japan soberly accepts defeat. A surrender is arranged, and a peace treaty is signed, in which, among other things, the formerly German Pacific islands, mandated to Japan by the League of Nations, are turned over to the United States “for their future administration”—precisely as happened after the actual surrender of Japan in 1945.

A BOYISH-LOOKING ISOROKU YAMAMOTO BEGAN SERVING as naval attaché at the Japanese Embassy in Washington soon after The Great Pacific War came out. Two years later, in 1928, Captain Yamamoto returned to Japan and delivered a lecture in which he presented Bywater’s ideas as his own. Many years later, as commander in chief of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Navy, Yamamoto put into practice a war plan astonishingly similar to that spelled out for Japan in The Great Pacific War.

Born in 1884—the year of Bywater’s birth—Yamamoto was small and fine-boned, slightly built even by Japanese standards. His left hand was missing the first two fingers, the most obvious of many wounds received at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. The injuries he sustained at Tsushima nearly disqualified him from continued service, but he nonetheless rose rapidly in the ranks.

Because the Imperial Navy regarded the United States as its most likely future opponent, the brightest young naval officers were sent there on various tours of duty. Yamamoto visited several ports on the West Coast aboard a training ship in 1909, studied English for a year at Harvard in 1919, returned for the Washington Conference on Naval Limitation in 1921, and finally took up his duties as naval attaché at the embassy in March 1926.

Yamamoto’s chief duty was to keep a close watch on the U.S. Navy. According to former Japanese naval attachés in Washington before the war, he gathered most of his information by carefully reading U.S. newspapers, magazines, and books. A voracious reader, he was well chosen for his work. At Harvard he had raced through four or five biographies of Abraham Lincoln before pronouncing Carl Sandburg’s the finest of the lot. At the Washington Conference, he scanned as many as forty newspapers and periodicals a day for references to Japan or to the Japanese proposals, such as one asking the United States not to fortify any naval bases west of Hawaii.

Thus, it would hardly be surprising if he seized upon The Great Pacific War. Bywater, after all, had written the important Sea Power in the Pacific and was the correspondent who during the Washington Conference had found out what Japan’s delegates were going to announce about such matters as her refusal to scrap the battleship Mutsu.

Did Yamamoto in fact read and react to The Great Pacific War? The most solid evidence would be among the reports from the naval attachés. However, all attaché reports written after 1921, and most records of the navy general staff (Gunreibu), which kept copies of these documents, were destroyed either by the American bombing of Tokyo on May 25, 1945 (which burned out half of the Navy Ministry building), or by the Japanese themselves just before American occupation troops arrived at the wads end.

Fortunately, the Diplomatic Record Office in Tokyo holds a treasure of revealing documents from the 1920s. These files show that during the time Yamamoto served as naval attaché, quite a number of Japanese officials assigned to the United States sent reports home about newspaper and journal articles on The Great Pacific War. such officials were close friends of Yamamoto, and in the opinion of former members of the Japanese diplomatic corps, his friends would not have failed to mention the book to him. Then again, Yamamoto may have brought the book to their attention.

The most convincing documentary evidence linking Bywater and Yamamoto appears in two top-level Japanese military briefing papers that deal predominantly with The Great Pacific War and the controversy surrounding it. Found in the Diplomatic Record Office, these documents remove all reasonable doubt that Yamamoto followed the controversy over The Great Pacific War and reported extensively on it.

Shortly after returning to Japan, Yamamoto delivered a lecture at the Imperial Navy Torpedo School at Yokosuka about the course of a possible future war between Japan and the United States. No text of the lecture exists. But the postwar Compilation Committee on the History of the Japanese Naval Air Force, which published a four-volume history in 1970, found and interviewed a former naval officer, Ichitaro Oshima, who recalled attending Yamamoto’s lecture at the Torpedo School.

“In the event of a future war between Japan and the United States,” Oshima recalled Yamamoto saying, “Japan will lose if she adopts the traditional defensive strategy. Japan’s only chance of victory would be to attack American forces at Hawaii.” According to Oshima, Yamamoto then went on to predict that aircraft carriers would soon replace battleships as the supreme weapon of naval war, and that the attack on Hawaii should therefore be made by naval aircraft.

Those words require careful analysis. What did Yamamoto mean by “American forces at Hawaii”? He surely could not have meant the handful of U.S. troops stationed there. Nor is it likely that he was thinking of Pearl Harbor as it existed at the time; in 1928 Pearl Harbor was merely a navy yard and supply depot, and no commissioned warships were based there. It appears that Yamamoto was looking to the future. In December 1926—10 months after taking up residence in Washington—he had learned that the U.S. Navy was planning to dredge nine million cubic yards of coral from the channel and anchorage at Pearl Harbor so that the base could accommodate a fleet of the largest warships. Thus, Yamamoto understood that in the not-too-distant future, a sizable American fleet would be stationed at Pearl Harbor.

But why attack an American fleet 3,374 miles from Tokyo? There can be only one explanation. Yamamoto envisioned Japan boldly extending the boundaries of her Pacific empire. A preemptive strike at Pearl Harbor would prevent American warships from interfering with highly vulnerable landing operations in the Philippines and perhaps on Guam. In short, Yamamoto was proposing the strategy for Japan that he had read about in The Great Pacific War.

Later, Yamamoto became acquainted with Bywater himself. In December 1934 the two spent an evening discussing Pacific strategy at a conference in London. It was one of several contacts between them.

Six years after this meeting, when war in the Pacific seemed inevitable and Yamamoto was concerned with contingency planning for the Imperial Navy, he fell back on Bywater’s ideas. Yamamoto’s strategy and tactics in launching war in the Pacific are strikingly similar to Bywater’s hypothetical scenario—right down to the beaches where invading forces would land.

Yamamoto’s grand strategy for the commencement of the Pacific war was twofold. First, he believed that Japanese forces must destroy the American Pacific Fleet outright. Second, they must quickly move into the resulting power vacuum and seize any territories that would expand the Japanese empire, so as to render it nearly invulnerable to attack. These objectives are spelled out in notes that Yamamoto gave to a Naval Academy classmate for safekeeping in January 1941, and in “Combined Fleet Top Secret Operation Order No. 1,” which Yamamoto and his staff prepared aboard the flagship Nagato and issued on November 5, 1941.

In deciding on the Pearl Harbor attack, Yamamoto was not simply following historical precedent, as has been frequently suggested. On the contrary, in his notes Yamamoto criticized the tactics of the Port Arthur attack of 1904, stating that “lessons must be learned” from Shigenori Togo’s failures in that action. He went on to say that unlike Togo at Port Arthur, he would employ a massive strike force at Pearl Harbor—in order to “thoroughly destroy the main body of the enemy fleet in the first moments of the war” (italics added). Once the American fleet had been disposed of, Japan could “occupy strategic places in East Asia [Guam, the Philippines, British Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies] to secure an invincible position.” Japan then “might be able to obtain her goals and secure the peace in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” That, of course, was precisely Bywater’s idea.

In mid-September 1941, Yamamoto attempted to demonstrate the feasibility of his plan at the annual Table Top Conference at the Imperial Naval War College—where Bywater’s Sea Power in the Pacific and The Great Pacific War were still being read. So passionate was Yamamoto about his plan that when the navy general staff balked at accepting it, he sent an emissary to Tokyo to declare that he and his entire staff would resign if not permitted to carry it out. Osami Nagano, chief of the navy general staff, was dismayed but finally said that the navy had to trust Yamamoto, who after all had been living with the problem longer than anyone else—a truer statement than he realized. Authorization from the highest councils of the government and the emperor followed quickly.

To cite one instance of Bywater’s profound influence, Yamamoto’s plan for invading the Philippines, demonstrated at the September Table Top Conference, conformed in great detail to the tactics spelled out in The Great Pacific War. Bywater had imagined simultaneous main landings—at Lingayen Gulf, at Lamon Bay between Cabalete and Alabat islands, and at Sindangan Bay on Mindanao. Astonishingly, the plan demonstrated at Yamamoto’s Table Top Conference consisted of roughly those same simultaneous landings in the Philippines—at Lingayen Gulf, at Lamon Bay between Cabalete and Alabat islands, and at Davao on Mindanao.

Yamamoto’s plans, of course, departed from Bywater’s scenario in certain respects. By the time Yamamoto folded into his master plan all the objectives of the Imperial Army, together with those of the navy general staff, he went far beyond Bywater, to include attacks on territories and forces of the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. The other important difference between Bywater and Yamamoto concerned the use of air power: Although Bywater eventually recognized its coming importance, the collective use of aircraft carriers, awesomely demonstrated at Pearl Harbor, was Yamamoto’s (and his air chief, Minoru Genda’s) contribution to naval science.

It is tempting to wonder what course events might have taken if Bywater had never written about strategy in the Pacific—or if Yamamoto had not been affected by the British author’s thinking. Quite possibly the war would have taken a very different course and left a much different mark on history. The military historian Louis Morton has written that if the Japanese had never conceived of the Pearl Harbor attack, had bypassed the Philippines and concentrated their territorial aggrandizement on the Dutch East Indies and British Malaya, “it is possible that the United States might not have gone to war, or, if it had, that the American people would have been more favorably disposed to a negotiated peace.”

Although Roosevelt was prepared to ask Congress to declare war on Japan if Japan attacked Singapore, no one knew how Congress—or the American people—might respond to such a request. In February 1941 a Gallup poll found that although 56 percent of Americans favored efforts “to keep Japan from seizing the Dutch East Indies and Singapore,” only 39 percent were willing to risk war to do so. Evidently, many were unwilling to commit American lives to help beleaguered European empires cling to their Asian colonies. After the Pearl Harbor attack, Secretary of State Cordell Hull said: “I don’t know whether we would have been at war yet if Japan had not attacked us.”

WHAT EFFECT DID BYWATER HAVE on the American conduct of the war?

He apparently knocked some sense into navy heads in 1925. Possibly having been informed about the American contingency plan for war with Japan, he devoted two chapters of The Great Pacific War to dramatizing the folly of the reckless expedition, such as proposed in War Plan Orange.

He then described the humbled U.S. Navy carrying out a carefully planned, step-by-step advance to Manila across a bridge of islands in the Marshall and Caroline chains. The visionary U.S. Marine Earl (“Pete”) Ellis and the air-power pioneer William (“Billy”) Mitchell made somewhat similar proposals, but Bywater was the first naval expert to publicly spell out such a campaign.

If Bywater could not precisely claim paternity for U.S. Pacific strategy, his writings undoubtedly influenced overall planning. Once the war broke out, most of the naval strategists working for the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, and for Chester W. Nimitz, the commander of the central Pacific theater, were familiar with The Great Pacific War—or one of its many imitations, such as Sutherland Denlinger’s War in the Pacific. Bywater’s ideas had become part of the naval culture.

Hector Bywater died in London on August 18, 1940, shortly after Yamamoto commenced secret preparations for carrying out the strategy he had conceived. The cause of death, according to the medical examiner’s report, was heart failure consistent with alcoholism. But one former colleague suspected that the Japanese, fearing that Bywater might unmask their preparations for a surprise attack, murdered him. No hard evidence supports this suspicion. Thus, about all that can be said with assurance is that Bywater’s sudden death in the summer of 1940 came as a gift for Isoroku Yamamoto—considering the course he was then embarked upon. MHQ

WILLIAM H. HONAN is the chief cultural correspondence of the New York Times. This article is adapted from his book Visions of Infamy: The Untold Story of How Journalist Hector C. Bywater Devised Plans that Led to Pearl Harbor, published by St. Martin’s Press.

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Spring 1991 issue (Vol. 3, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Bywater’s Pacific War Prophecy

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!