From her earliest years, Elizabeth Southerden Thompson admired soldiers. A talented artist, she devoted her career to depicting battle scenes and men of war. Her skill at military artwork was so impressive that she became a sensation in Victorian Britain—when a female military artist was a phenomenon.

“My own reading of war … is that it calls forth the noblest and the basest impulses of human nature,” she later wrote in a 1922 autobiography.

Born in 1846, the attractive and energetic young Elizabeth, nicknamed “Mimi,” was a rarity during an era when most women artists painted flowers and landscapes.

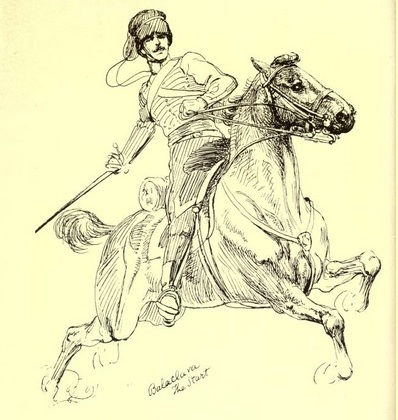

“I stuffed my sketchbooks with British volunteers in every conceivable uniform, each corps dressed after its own taste,” she wrote. Scenes from her early sketchbooks depict soldiers in a variety of situations—drinking, smoking, marching, shooting, and charging on horseback.

“I gave sketches to nearly all my fellow students—fights round standards, cavalry charges, thundering guns,” she wrote of her early days in art school.

Her interest in war and battles baffled many. There was no military tradition on either side of her family. Her devout mother, horrified by war, disapproved and wished her daughter to pursue a career in religious art. However, Mimi was immovable in her resolve.

The determined young lady repeatedly sent drawings of soldiers to the Illustrated London News. Although her sketches were rejected for publication, she pursued her interests. At a time when other respectable British women dabbled in delicate watercolors, Mimi produced violent and realistic battle scenes of cavalry and artillery.

Watching an army corps engage in a mock battle, she described the soldiers as having “a rather savage look which I much enjoyed.” In her autobiography, she often described soldiers as “splendid” and “gallant” and wrote of her enthusiasm for listening to veterans’ war stories. Invited to lunch in an army field mess hall, she remarked: “The lunch at the Welsh Fusiliers’ mess in a tent I thought very nice.”

The 26-year-old Mimi unexpectedly skyrocketed to fame when her 1874 painting “The Roll Call,” depicting war-weary troops after the Battle of Inkerman, was put on display at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Onlookers were astonished by the gritty realism of the painting and especially by the fact that a woman created it. The painting, coveted by many, was bought by Queen Victoria.

Mimi subsequently became famous, which she found difficult. She was criticized in the newspapers. However, her work was in demand. Hundreds of British soldiers and officers were eager to model for her. This resulted in the creation of many of her greatest masterpieces. Mimi depicted scenes from the Napoleonic Wars, 19th century wars and eventually World War I.

Mimi’s fame also brought her future husband—a rugged infantryman named Sir William Butler. Butler was a rowdy Irishman who served with distinction in the Canadian Red River Expedition and in sub-Saharan Africa. Newly promoted to major, he was bedridden in England’s Netley Hospital recovering from a severe fever he caught on the frontlines when his sister read him newspapers to alleviate his boredom. Hearing of Mimi the feisty war painter, Butler was impressed.

“As paper after paper spoke of me and of my work, he said one day to his sister, in utter fun under his slowly reviving spirits, ‘I wonder if Miss Thompson would marry me?’” Mimi recalled in her memoirs. “Two years after that he met me for the first time, and yet another year was to go by before the Fates said ‘Now!’” Following her marriage, Mimi became known as Lady Butler.

She went through great lengths to recreate battle scenes. She used real soldiers as models and occasionally policemen. Mimi asked models to fire guns for her to so she could recreate realistic gun smoke. Once she also asked cavalrymen to charge at her.

“I was favored with a charge, two troopers riding full tilt at me and pulling up within two yards of where I stood, covering me with sawdust,” she wrote. “I stood it bravely the second time, but the first I got out of the way.”

One of her famous works was her 1875 mural, “The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras,” depicting events from the 1815 battle described in a military history book she read. The painting proved popular when unveiled. She wrote in her diary on May 3, 1875: “A dense, surging multitude before my picture. The whole place was crowded so that before ‘Quatre Bras’ the jammed people numbered in dozens and the picture was most completely and satisfactorily rendered invisible … It was chaos ….They clashed in front of that canvas and, in struggling to wriggle out, lunged right against it.”

Other notable works by Lady “Mimi” Butler include “The Defence of Rorke’s Drift” (1880) and “Scotland Forever!” (1881). She also sketched a variety of soldiers in action from different countries, including an Egyptian camel corps charge and Italian Bersaglieri troopers marching to trumpets.

Lady Butler’s paintings were unique in depicting suffering and the individuality of soldiers in addition to their heroism. She emphasized tragedy with triumph. “I hope my military pictures will have moral and artistic qualities not generally thought necessary to military genre,” she wrote in her diary.

One of Lady Butler’s most moving works was her 1882 painting “Floreat Etona!”, which depicts the heroism of a British officer immediately before his death at the Battle of Laing’s Nek in the Boer War. Lieutenant Robert Elwes, an alumnus of Eton College, shouted his university motto to inspire a former schoolmate during battle. Elwes was killed by gunfire minutes later.

Through her Irish Catholic husband, Lady Butler became increasingly aware of hardships faced by people in Ireland and attempted to use her art to advocate for the Irish cause in Britain. As a result, she fell into disfavor with British imperialists who formerly admired her paintings. Persistent, Lady Butler continued to pursue her interests and paint military scenes until her death in 1933. She remains one of the most notable British military artists in history.