It was a chilly fall morning in western Missouri, and George Thoman was a decidedly unhappy man. Rebel soldiers operating near Thoman’s residence in Westport had stolen his horse during the night, and the immigrant farmer from the Franco-German province of Alsace wasn’t going to let the matter rest. Little did Thoman realize he was about to play a critical role in what would be the largest battle fought west of the Mississippi River during the Civil War. That missing horse not only helped turn the battle’s outcome, for all intents it put an end to Southern hopes in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

In 1856, Thoman left Alsace for a new life in America, making his way to Jackson County, Mo., with an opportunity to farm a plot of land just south of Brush Creek, a small stream running east from the Kansas border to the Big Blue River, a tributary of the Missouri River. Thoman, however, soon found it impossible to ignore the increasingly troubled state of affairs along the Missouri–Kansas border, which made engaging in meaningful economic activity in the western Missouri countryside problematic. By the fall of 1864, Thoman and his family had relocated to the home of a friend in nearby Westport, his decision to do so undoubtedly influenced by Union Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing’s General Orders No. 11, which mandated the relocation of potential Confederate-leaning residents from the countryside to more settled points in western Missouri.

Westport was a jumping-off point for those heading west on the Santa Fe and Oregon trails and, therefore, was at the peak of its prosperity when the fractious slavery debate in the region turned violent in the 1850s. Sizable Union and Confederate armies happened to be operating around Westport in October 1864. Inevitably those armies would clash.

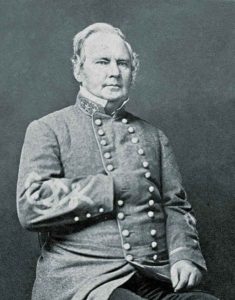

Major General Sterling Price commanded the Confederate force, the Army of Missouri. A former governor of the Show Me State, Price led victories at Wilson’s Creek and Lexington in 1861 that elevated his stature among pro-Confederate Missourians beyond what his abilities merited. Unfortunately for the South, by the time Price’s command entered Jackson County in October 1864, the limits of what it and its commander were capable of were quite evident. To be sure, in the time since Price and his men had crossed the border from Arkansas into southeast Missouri on September 19, they did manage to cover an impressive distance in the course of a whirlwind campaign—highlighted by engagements at places such as Pilot Knob, Glasgow, and Boonville. Yet, for all the noise produced by Price’s activities, there was precious little proof they had done much to shake the grip Federal authorities enjoyed on the state.

What Price and his men were undeniably capable of was bringing the hard hand of war to those they deemed insufficiently sympathetic to the Southern cause. That would unfortunately include George Thoman. During the 1850s, a major influx of European settlers into Missouri became a significant source of friction within the state. Many of these newcomers were influenced by the liberal ideals of the European revolutions of 1848-49. That, combined with their sheer numbers, aroused great anxiety in Missouri, especially among the conservative slaveholding elite that had traditionally dominated the state’s politics and economy. Further exacerbating tensions was the fact that Missouri’s German population provided the manpower behind the May 1861 coup led by Union Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyons that overthrew Missouri’s duly elected—but proslavery—government.

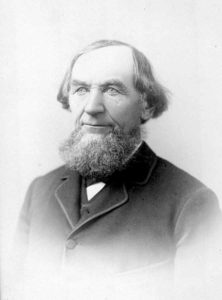

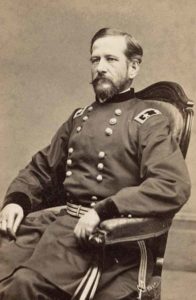

Price had long hoped he could drive the state’s provisional government from power or at least pose a serious menace to St. Louis, the lifeblood city on the Mississippi River. By October 1864, however, those were essentially just dreams and his command’s operations had degenerated into little more than a looting expedition. Moreover, by that point Federal authorities had directed Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis to assemble what would be called the Army of the Border to defend Kansas, and had ordered Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans—in charge in St. Louis—to dispatch a force, commanded by Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, to chase Price as he ventured along the Missouri River toward Kansas.

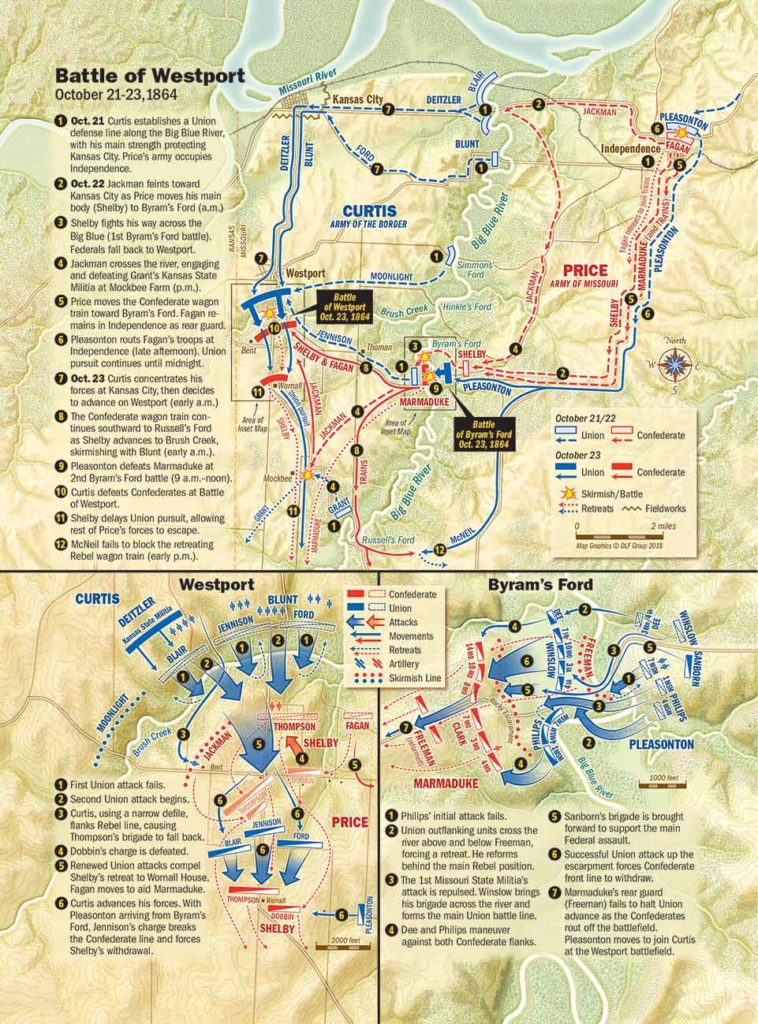

As a consequence, on October 22, Price found himself in a decidedly challenging position. Curtis’ command was in his front, and the gap between it and Pleasonton’s was rapidly diminishing. Furthermore, the general’s ability to move with the expediency the situation required was seriously hampered by some 600 wagons laden with property that had been liberated from various Missourians.

Price was fortunate that day to claim a tactical success when he defeated elements of Curtis’ command at Byram’s Ford, a Union-defended crossing point of the Big Blue River. Aware that Pleasonton’s force was on Price’s heels and could be expected at the Big Blue the next day, Curtis’ response to the setback was to place the Army of the Border in good position “within the lines of field works that inclosed Kansas City” and leave a small force at Westport.

Curtis’ actions, though, left considerable real estate exposed to the depredations of Price’s Confederates on October 22. However sensible the decision might have been from a military standpoint, it proved quite unfortunate for George Thoman, as soldiers likely from Price’s command found their way to his residence that night. After the intruders made off with hams and tableware, Thoman became frazzled by their interest in his gray mare, which was about to give birth. Thoman’s vehement, heavily accented objections proved unavailing.

Anyone pondering the military situation as the sun rose over Brush Creek on October 23 could be forgiven for believing the stealing of a single horse and the distress it caused its owner were of little consequence. During the night, Price decided he and the 8,000–9,000 men still with his command would fight. If he could somehow take advantage of his possession of interior lines to win a victory, it might reverse the perception of his raid as a waste of time and effort. This would be the best scenario, though admittedly a long shot.

At the least, Price thought his men could put up enough of a fight to provide sufficient space and time for the wagon train to get away from danger. Thus, Price decided to post Brig. Gen. John S. Marmaduke’s Division at Byram’s Ford to fend off Pleasonton. His other two divisions, under Brig. Gen. Joseph O. Shelby and Maj. Gen. James Fagan, would advance north from positions south of Brush Creek and attack whatever elements of Curtis’ command might be found.

For his part, by 3 a.m. on October 23, Curtis was confident his force of about 15,000 men was in good position to move against Price’s command. “My purpose,” he informed Pleasonton, “[is to] attack…the enemy at daylight.” Under the direction of division commander Maj. Gen. James Blunt, Colonel Charles Jennison’s and Colonel James H. Ford’s brigades, supported by Colonel Charles W. Blair’s, would advance from Westport to Brush Creek, which was “skirted by a dense forest some two miles wide.” After crossing the creek, Blunt’s men were to continue their push south through the timber following a road that passed the house of John Wornall, a mile and a half south of the stream, and attack any Confederates they might find on the open prairie. On the Union right, a brigade commanded by Colonel Thomas Moonlight would advance to a position from which it could defend Kansas along the road that marked the border with Missouri, while menacing the western flank of any enemy force Blunt might encounter. If Pleasonton could quickly defeat Marmaduke at Byram’s Ford and Blunt do the same to the Rebels south of Brush Creek, a victory putting the very existence of Price’s army in jeopardy was a distinct possibility.

The morning of October 23, however, would be a frustrating one for the Army of the Border. At daylight, Jennison’s and Ford’s commands were ready for action and their commanders promptly ordered them across Brush Creek, breaking the thin layer of ice that covered the water, and then up the heights on the south side. With skirmishers leading the way through the mist that covered the prairie, Blunt’s 1,500 or so men continued their advance south. At that point, though, Shelby’s and James Fagan’s divisions were moving north from their camps near the Wornall House to see what they could do. Shelby later proclaimed it was a day “clear, cold, and full of promise.”

When the two sides made contact north of Wornall’s home, it became clear rather quickly that the Rebels had more effectively massed their forces. After about an hour of fighting, in which “clouds of dense and sable smoke…draped the scene,” Jennison’s and Ford’s commands were pushed back to the cover of the timber along Brush Creek. Moonlight, meanwhile, fell back toward Shawnee Mission. Blunt’s men did force the Confederates to expend so much ammunition, though, that Shelby couldn’t press his advantage. Thus, as the Federals crossed back to the north side of Brush Creek, Shelby and Fagan were content simply to take up a defensive position on the high ground overlooking the creek and push skirmishers forward into the timber south of the creek.

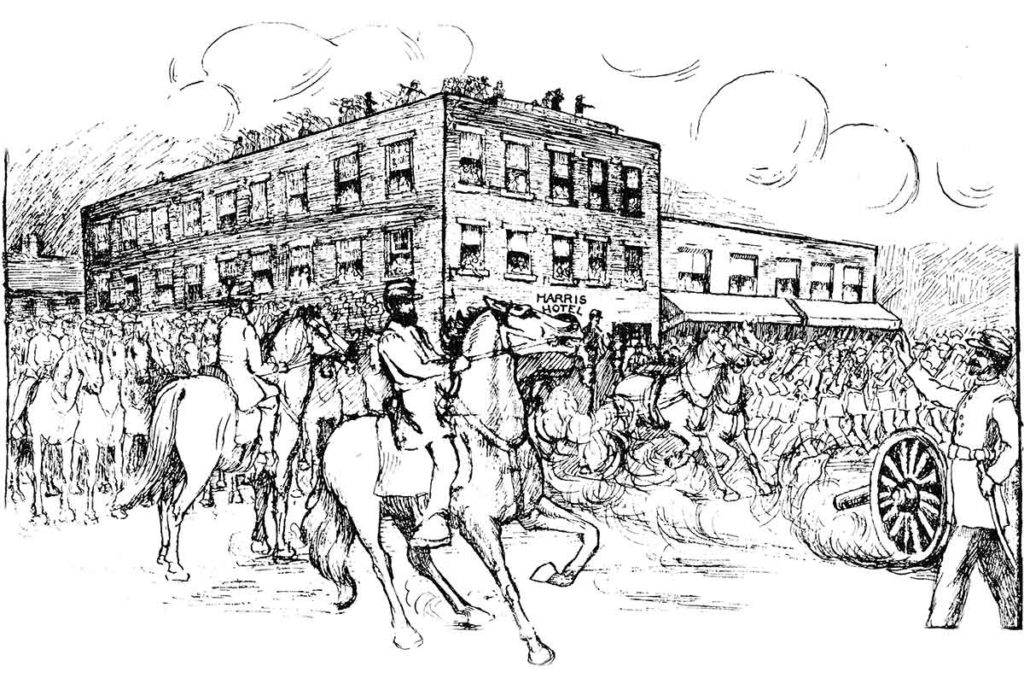

As this was going on, Curtis made his way to the roof of the Harris House Hotel in Westport to get a sense of the morning’s fighting. He learned the enemy had skirmishers in the timber south of Brush Creek and could see beyond “rebel lines deployed in endless lines on the open prairie.” With his men along the creek exchanging what Jennison described as “a desultory fire” with the Confederates, the redoubtable Federal commander ordered reinforcements forward and directed Blunt to make vigorous use of his artillery. Then, as Blair’s brigade advanced to the front line, Curtis decided to take a more hands-on approach. Accompanied by the six guns of Captain James H. Dodge’s 9th Wisconsin Battery—which since April had spent most its time protecting wagon trains along the Santa Fe Trail—he made his way personally to Brush Creek.

Although Price had established army headquarters east of the Wornall House in order to keep an eye on the fighting at both Brush Creek and Byram’s Ford, he spent the night with Shelby’s and Fagan’s commands near that home. Price later declared he was “in full view of Generals Fagan and Shelby” during the fighting, but he clearly had little direct influence on the outcome of the battle along Brush Creek. The same could not be said of Curtis.

In any case, despite the arrival of Blair’s brigade and Curtis’ personal presence at Brush Creek, things looked promising for the Army of Missouri about 11 a.m. All attacks by the Federals proved to be exercises in futility. As his beaten men once again fell back to the woods along Brush Creek, it must have seemed to Curtis that whatever hopes existed of a Federal victory that day rested on Pleasonton’s shoulders.

But there was little evidence Pleasonton’s 5,500-man command was faring much better. By 11 a.m. the Federals had fought their way across the Big Blue, only to find Marmaduke occupying a strong position on a rock ledge overlooking an open meadow. Not until noon could Pleasonton get enough men into the fight to get the upper hand on Marmaduke, with Lt. Col. Frederick Benteen’s brigade driving the Rebels from what they called “Bloody Hill.”

As Marmaduke’s men fell back, Pleasonton ordered his troopers to pursue. By the time the Confederates reached Harrisonville Road, the Army of Missouri seemed in serious trouble. A Union victory was now quite possible, but the extent of that victory would depend on whether Curtis could find a solution to the problem he faced along Brush Creek.

Regardless of the sounds of battle filling the air that morning, it was insufficient to blunt Thoman’s determination to locate and reclaim possession of his stolen mare. By 11 a.m., his search had brought him close to the Union lines and the desperate Curtis. In interviewing Thoman, the Federal commander learned that a few hundred yards west of Wornall Road a stream flowed into Brush Creek from the south and west that cut a defile into the heights upon which the enemy was posted. According to Thoman, this defile—known as Swan Creek—could be used to maneuver behind the Confederates undetected.

Curtis wasted no time. He promptly assembled a force composed of Dodge’s gunners and his own personal escort and, guided by Thoman, was soon following the new route. (Curtis owed his most notable military accomplishment of the war to that point, the victory at Pea Ridge in March 1862, largely to the superiority of his artillery, which undoubtedly shaped his thinking as he put together this force.) Meanwhile, under Blunt’s direction, the Federals at Brush Creek once again ventured forward to test the enemy line—though given the way the past few hours had played out, those in the ranks could certainly have been forgiven for wondering why their commanders expected a better result than previous efforts.

As Thoman had promised, by following the Swan Creek defile, Curtis and his force made their way undetected to a point just south and west of the home occupied by famed Western Indian agent and fur trader William Bent.

With his force now to the left and rear of the Confederates’ Brush Creek line, Curtis had Dodge fire his guns upon Shelby’s and Fagan’s commands. This, as well as a renewed push by Blunt, was too much. The Rebels fell back about a half-mile to the south, to a new line along a lane running west from the Wornall House to the Bent House.

Price, alerted that his wagon train was in danger, told Shelby and Fagan to hold on as long as they could. Curtis pushed his artillery forward, with 30 pieces soon in action. “Both armies were now in full view of each other on the open prairie,” a Union officer later declared, “presenting one of the most magnificent spectacles in nature.”

Curtis’ army then advanced, forcing a valiant but ultimately fruitless response from the Confederates. The weight of Federal power proved too great. Realizing they had no chance to hold out, Shelby and Fagan called for a retreat. As their lines began to crack, a unit of Arkansas cavalry was ordered to make a charge on a Colorado battery whose fire had been taking an especially heavy toll on the Confederate position. That prompted Jennison to personally lead Captain Curtis Johnson’s company of the 15th Kansas in a countercharge. A ferocious melee ensued. The Federals emerged victorious, helped by the arrival of two squadrons of Colorado cavalry.

“Both armies were now in full view…presenting one of the most magnificent spectacles in nature”

Nevertheless, Shelby managed to establish a new line in the vicinity of the Wornall House. It did not hold for long, however. With Pleasonton pressing west to and beyond the Harrisonville Road and threatening the right and rear of the army, the Confederate commanders decided the only option was to send reinforcements from their fight with Curtis to Marmaduke’s aid. A fierce engagement with Pleasonton’s cavalry at the Thomas Mockbee Farm ended with a Confederate retreat, but critical time had been bought for Price’s beleaguered army to escape. A brief stand by Shelby’s cavalry also failed, and the rout was complete.

As night fell October 23, Curtis, Pleasonton, and their men could take great satisfaction in their efforts that day. Though Price did get his wagon train away, the broken remnants of the Confederate army retreating south left no doubt the Union army had pulled off a truly decisive victory.

Sadly, whether George Thoman’s contribution to the Union effort resulted in reunion with his missing horse has been lost to history.

Ethan S. Rafuse is Charles Boal Ewing Chair in Military History at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, N.Y.

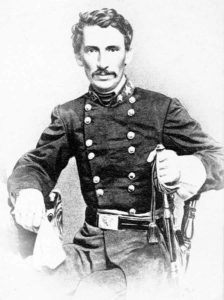

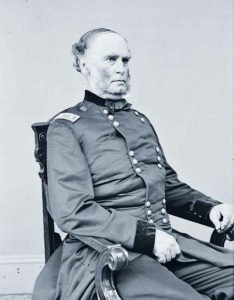

The Swamp Fox

Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson led Jo Shelby’s famed “Iron Brigade” at Westport. A transplanted Virginian, Thompson, born Meriweather Jeff, moved to western Missouri as a 21-year old in 1847. After working as a railroad surveyor and engineer in St. Joseph, he turned to politics and served as the city’s mayor (1857-60). As the nation drifted into civil war in the spring of 1861, he was appointed colonel and then brigadier general in the Missouri State Guard (MSG). Although this border state’s population was split on slavery and secession, pro-South politicians controlled the state government. At the war’s outset, Thompson was assigned defense of waterlogged, marshy southeastern Missouri, earning the nickname “The Swamp Fox of the Confederacy.” A Confederate sidewheel ram was named in his honor.

Despite early Confederate victories at Wilson’s Creek and Lexington, the Federals soon gained control of Missouri. Following a loss at Fredericktown in October 1861, Thompson fled into northern Arkansas. He led ironclad rams in Confederate riverine forces and participated in John Marmaduke’s famed 1863 raid into Missouri. Captured later that year, Thompson was exchanged for a Union general in early 1864. He commanded the Iron Brigade for the first time during Price’s Raid in 1864.

Thompson unsuccessfully petitioned Richmond for a Confederate commission and ended up retaining his MSG generalship throughout the conflict. Moving to New Orleans after the war, he worked as an engineer draining Louisiana swamps until 1876 when, terminally ill with tuberculosis, he returned to St. Joseph. He died there that September. —Jerry Morelock