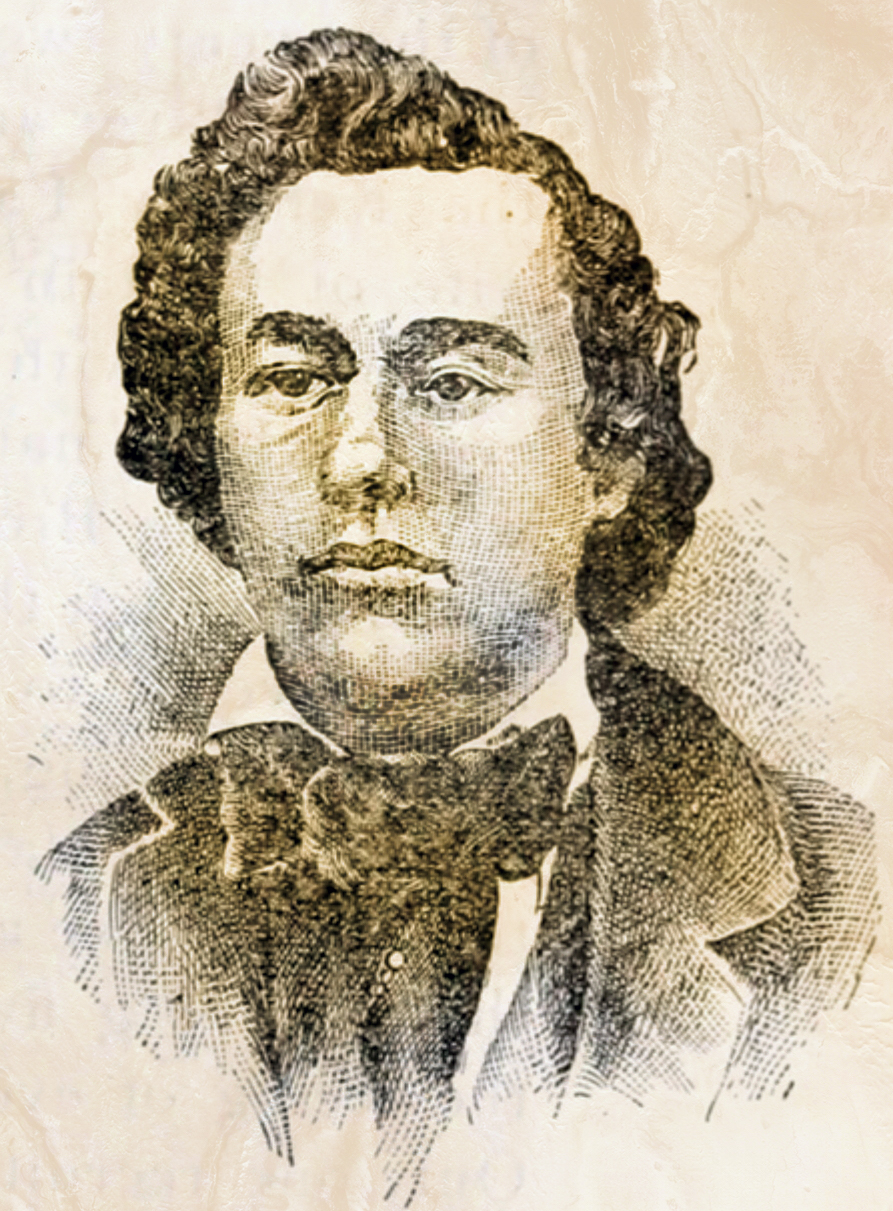

John E. Cook was a law clerk, dandy, womanizer and excellent shot. And he was John Brown’s eyes and ears in Harpers Ferry, Va., before Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal there in October 1859. In his new book, Steven Lubet details Cook’s role during the insurrection—kidnapping white hostages outside the town, including George Washington’s grand-nephew Lewis Washington—and the consequences of Cook’s actions for himself, for Brown and for their co-conspirators. After he delivered the hostages to Brown at the armory, Cook was sent across the Potomac River to Maryland to join co-conspirators Charles P. Tidd, Francis Merriam, Barclay Coppoc and Owen Brown. But when they learned Brown and the rest of his “army” at Harpers Ferry were surrounded by federal troops led by Robert E. Lee and Jeb Stuart, Cook and the other fugitives decided to run to the north…but with one fateful detour.

It would be a long time before Cook and his fleeing companions fully learned what happened to John Brown at Harpers Ferry. As Jeb Stuart’s men were taking control of the armory, the five fugitives huddled anxiously on a mountainside wondering how they could escape. Maryland was hostile territory, and southern Pennsylvania was not much better. The nearest refuge was probably close to 100 miles away by road in western Pennsylvania, but they could not take the roads. Their ultimate objective, the Western Reserve of northeast Ohio, was hundreds of miles farther still. It was all but impossible to imagine how far they would have to walk over rough, densely wooded terrain. With only the provisions they could carry on their backs, they braced themselves for a cold, wet, desperate and dangerous march.

More than any of the others, Cook understood he was a wanted man. He was familiar to many in Harpers Ferry, and could be named—and identified—by Lewis Washington and other locals.

In fact, Washington provided Cook’s name to the authorities immediately after being rescued by Stuart’s unit in Harpers Ferry. The following morning, Wednesday, October 19, Washington executed an affidavit in which he swore “that a certain John E. Cook” was part of the kidnapping party, “affiant having distinctly recognized him when he was seized and robbed of his property.” Washington added that Cook “is now a fugitive from justice [and] he is fleeing and attempting to escape in the state of Maryland, Pennsylvania, or New York.” A warrant for Cook’s arrest was issued, and Virginia Governor Henry Wise promptly offered a $1,000 reward for Cook’s capture. Handbills were distributed in three states, and newspaper reports published across the country gave Lewis Washington’s unflattering description of Cook:

Five feet four to six inches high; weighs 132 pounds; walks with his breast projecting forward, and his head leaning toward the right side; has light hair, with a small growth around the upper lip, is of sallow complexion, and has a sharp, narrow face.

For a short while, Cook was one of the two most famous militants in the country, second only to John Brown himself. The Richmond Enquirer, for example, immediately blamed the insurrection on “the scoundrels Brown and Cooke,” with Cook identified as “Brown’s chief aid [sic].” In a speech in Richmond, Wise described Brown’s defeat in great detail and singled out Cook’s involvement. Wise mentioned Cook five times (more than any of the other known raiders, save Brown), accurately describing his spying mission, his census of slaves and his surveillance of the armory. Wise even accused Cook of murdering a slave who “attempted to escape from him.”

The authorities eventually realized other raiders had escaped, but only Cook could be identified. Under interrogation, Brown admitted “three white men [had been] sent away on an errand” and thus were not captured or killed, but he refused to disclose their names. Consequently, the first reward announcement named only Cook, while referring to another three unknown white men; it did not identify Barclay Coppoc, Charles Tidd, Francis Merriam or Owen Brown. Other early accounts of the raid, including Robert E. Lee’s initial report to the War Department, listed only “Capt. John E. Cook of Connecticut” as having escaped. Perhaps their own anonymity brought some small comfort to the other four refugees, who realized Cook alone was known in Harpers Ferry. But they also knew they were being hunted, and it was worth their lives to remain out of sight.

In fact, the fugitives probably could have been captured quickly following the raid, but neither Virginia nor Maryland authorities took effective pursuit. Local militia men had mostly gotten drunk on Tuesday, following Stuart’s operation, and their revels continued all day Wednesday. Lee’s regular troops were more disciplined, but had their hands full maintaining order in town and preventing a lynching. Wise was busy interrogating Brown, trying to determine whether more armed abolitionists were about to descend on Virginia.

It took the rumor of an atrocity to get the manhunt started, when a story spread that Cook’s men had attacked the village of Pleasant Valley, Md., and a white family had been massacred in its cabin. Lee was skeptical, but he could not ignore the frantic stories of “cries of murder and screams of the women and children.” Refugees from outlying towns were pouring into Harpers Ferry, fleeing from imaginary abolitionist marauders, so Lee led a detachment of two dozen men to the “outraged hamlet, four or five miles away” and found the local residents quiet and unharmed. There had never been any danger of a further abolitionist attack, but in fact Cook’s party was at that time hiding on the outskirts of Pleasant Valley, quite unknown to Lee. They were close enough to hear the hoofbeats of the federal troops “which made them wrongfully believe that they were discovered,” but the soldiers rode past them in ignorance while they hid silently in the brush.

Cook’s university studies and work as a Brooklyn law clerk had not prepared him for endless tracking through the wilderness—nor had his comfortable year at a Harpers Ferry boardinghouse—but he was in good health and had been hardened by his anti-slavery service with John Brown in Kansas. Three of his comrades were in worse shape; their various disabilities would cause many difficulties as they tried to escape from Maryland to the North.

Owen Brown was the third of John Brown’s many children. His most noticeable feature was his crippled arm, which he injured as a young child. The injury had not kept Owen from serving with his father in Kansas and participating in the Pottawatomie massacre, but his limited range of motion did prevent him from undertaking the most strenuous physical tasks. In worse shape was Barclay Coppoc, an Iowa Quaker whose brother Edwin had been captured at the armory. Coppoc was “touched with consumption” that taxed his endurance and often made it difficult to walk. Still he managed to keep up, never complaining about the hardship. Francis Merriam had lost an eye as a youngster, but that was the least of his problems. He was the “frail scion of upper-class Boston,” a wealthy young man considered erratic and unbalanced even by his friends. His initial attempt to join Brown was rejected because of his infirmities, but he was later accepted when he contributed substantial financial resources when Brown was desperate for money.

Merriam was useless for combat, which is why Brown would not let him participate in the raid. To the dismay of the other fugitives, he also turned out to be nearly incapable of escape, needing constant assistance to make his way through the thickets and streams.

Charles Tidd was easily the strongest of the fugitives. The former lumberjack from Maine had broad shoulders, sturdy legs and muscular arms. Unfortunately, there were intense personal difficulties between Cook and Tidd that caused greater problems than any of the other men’s physical shortcomings. They had been assigned to work together during most of the raid—first cutting the Harpers Ferry telegraph lines, then kidnapping Washington and others—but that did not mean they could easily cooperate as fugitives.

Cook believed he should be the group’s leader, and he wanted to risk traveling by road—and even to steal horses—in order to make more rapid progress toward safety. Tidd wanted to stay as much as possible in the mountains, where he believed the crags and laurel bushes would discourage pursuers. In short order, the disagreement became bitter, as Tidd was not impressed by Cook’s schooling, rank or arguments. A much larger and slower man than Cook, Tidd was not afraid of a fight but he was cautious and shocked by Cook’s appalling braggadocio during the first days of their flight. They might have come to blows, or perhaps parted ways, had not Owen Brown intervened in favor of following the mountain ranges rather than roads. Even so, it took all of Brown’s negotiating skills to hold the small band together. “It was not easy work to separate Cook and Tidd,” Brown later recalled, but he succeeded in persuading them to wait “to have it out [until] they could do it without endangering others.”

It turned out Tidd was right. When the first posses were finally organized to chase the Harpers Ferry fugitives, they kept entirely to the roads and were therefore relatively easy to evade.

Sticking to their plan, the raiders hid “by day in the thickets on the uninhabited mountain-tops.” Doing their best to avoid all human contact, they spoke only in whispers and shunned “all traveled roads at all times, except as we were obliged to cross them in the night.” They waded through streams to throw bloodhounds off their trail, and refrained from lighting campfires for fear of being discovered. Their provisions—mostly dry biscuits and sugar—ran out after only a few days, and they were eventually reduced to scavenging fields and orchards for whatever crops remained, or stealing food from unattended farmyards and henhouses.

At Cook’s insistence, the group headed almost due north toward Chambersburg, Pa. There were good reasons to go to Chambersburg, and also good reasons to avoid it. Franklin County, where the town is situated, was almost evenly divided on slavery, with slightly more Republicans than Southern-oriented Democrats. Many Democrats were also sympathetic to fugitive slaves. Chambersburg was therefore an important station for runaways following the Underground Railroad from Virginia, through Hagerstown, Md., and into Pennsylvania. Even local judges, though sworn to uphold the Fugitive Slave Act, were often willing to “feed the trembling sable fugitive, hide him from his pursuers, and bid him Godspeed on his journey toward the North Star.”

Franklin County’s resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act must have suggested other anti-slavery fugitives could find shelter as well. But Chambersburg was such an obvious destination it was certain to be among the first places any bounty hunters would search for the Harpers Ferry escapees. Reward notices for Cook were circulated in Chambersburg almost immediately following the raid.

It might have made more sense to travel more sharply northwest toward Ohio, but Cook’s wife and child were in Chambersburg, and he was determined to go there. Brown objected, worrying it crossed too many valleys and roads.

Unlike the others, Brown had once before made the trip between Maryland and Chambersburg on foot. But despite Brown’s experience, the others deferred to Cook. He was the only married man in the group, and they sympathized with his hope of finding his family. Brown, too, finally consented to head toward Chambersburg.

As he had warned, the route took them through the Cumberland Valley, where they had to cross the well-traveled and patrolled road between Hagerstown and Baltimore. After nearly a week—they did not know the precise date as they had “no time-piece in the party” and had lost track of the days—they approached the perilous gap in the mountains, only to see that “horsemen were scampering hither and thither on the highways, and the whole country, it seemed, was under arms.” They heard the constant baying of bloodhounds and saw the alarm fires of the bounty hunters. As Brown observed, “there was nothing like safety for us till we should get across that pike.” Their first forays failed because the constant presence of armed men and dogs stopped them from getting anywhere near the road. Finally, at about midnight, they found a seemingly deserted stretch of the pike and made a dash for it, eventually crossing into Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania did not bring safety. The terrain was dangerous and so were many of the people. Cook tripped on the first night after crossing the state line, falling down a steep, rocky gorge. He was severely bruised and limped badly for days. More treacherous, however, were the pro-slavery citizens of Pennsylvania’s South Mountain region, many of whom supplemented their incomes by hunting fugitive slaves.

Finally, after hiking more than 100 miles, the party was within 15 miles of Chambersburg. Tidd and Brown decided to scout for the best route through the next valley while Cook remained behind with Merriam and Coppoc. Tidd and Brown advanced about a mile and a half when they saw a farmhouse. Sneaking to within 200 yards of the homestead, they were overcome by “the smell of something like doughnuts cooking.” Tidd had remained stoic through the long days and nights of hunger and exhaustion, but now the smell of distant cooking made him stagger. He “vowed he wouldn’t go a step farther without food,” and told Brown he was going to head for the farmhouse. “It is just as well to expose ourselves one way as another,” he said.

Brown was certain Tidd would immediately be suspected as a Harpers Ferry fugitive and would never be able to bluff his way out of trouble if questioned. Brown therefore pleaded with him to return to the others, promising to devise a plan to obtain some food. Back at camp, everyone agreed Cook should be the one to go after provisions. After all, “he could wield the glibbest tongue, and tell the best story.

John Cook was almost glib enough. He had always been able to make friends with strangers—as he had so easily during his year as a spy in Harpers Ferry—and the farm family in the valley proved no exception. They readily accepted Cook’s story that he was a member of a hunting party lost in the hills, and invited him to stay for a meal. The splendid visit, as Cook put it, lasted several hours, and he returned to his friends bearing “a couple of loaves of bread…some good boiled beef, and a pie” he had purchased at the farm. They feasted on the supplies, enjoying their first real meal in over a week.

Perhaps giddy on a full stomach, Cook revealed he was carrying the “old-fashioned, one barrel” pistol that had belonged to Revolutionary War general Marquis de Lafayette, which he had stolen from Lewis Washington and withheld from John Brown. He began firing the gun at random in what he claimed was an effort to carry out “the story of our being hunters.”

For Tidd, that was almost the final straw. The farm family had never questioned the existence of a hunting party, so there was no reason to keep up any pretense, and nothing good could happen if anyone else decided to investigate Cook’s gunshots. Tidd brusquely demanded a stop to the firing, but Cook refused, saying “he knew what he was doing and would not take orders.” Fearing a fistfight—or even a gunfight—would break out, Brown rushed to get between them. With Coppoc’s assistance, and Merriam lying helplessly on the ground, he finally separated the two belligerents, but only for the time being.

Things were not much better the next day, October 26, as the group continued toward Chambersburg. Brown was in a hurry to get as far as possible from the place where the gunfire had occurred, and was therefore willing to risk traveling by daylight. All morning Cook complained about Tidd, making renewed threats. In calmer moments, he expressed happiness about his “prospective meeting with his wife and boy in Chambersburg,” but his anger at Tidd was never far from the surface. Brown wasn’t sure which was more dangerous. The bickering with Tidd threatened the group’s fragile cohesion, but any attempt to visit Cook’s family was likely to draw the attention of bounty hunters.

At mid-afternoon the party stopped to rest by a spring. Coppoc volunteered to go on a search for more provisions, and the others readily agreed. Brown again failed to dissuade them. Realizing the frail Coppoc was poorly suited to the task, Brown said, “Cook was the man most fitted to the mission.” Cook had no objection, eager to get away from Tidd. Taking several dollars from Brown and carrying only a revolver hidden in his waistband, Cook departed “between three and four o’clock in the afternoon.”

They expected Cook to come back in a few hours, but he had not returned by dusk. They waited until dark, and then “till nine o’clock, till midnight, and still he did not come.” Hoping Cook had only gotten lost, they “lingered about, calling and watching for him till at least two o’clock in the morning.”

Now fearful for their own safety, they broke camp in the middle of the night. Tidd gathered up a few of Cook’s belongings, including Lafayette’s single-shot pistol. But the rest of Cook’s gear—and more—had to be abandoned. Neither Coppoc nor Merriam was strong enough to handle an extra load, and there was a limit to how much Tidd could carry.

There were two Logan brothers, Daniel and Hugh, living in southern Franklin County between Chambersburg and the Maryland border. The Logans were “shrewd, quiet, resolute men, both strongly Southern in their sympathies…and both trained in the summary rendition of fugitive slaves without process of law.” They had ample opportunities to ply their trade, as it was common for slaves to escape from Maryland and Virginia into the South Mountain district. Rather than form their own hunting parties, aggrieved slaveowners would circulate handbills describing fugitives and offering rewards for their capture. The Logan brothers made a solid living tracking runaways.

Daniel was the younger and more intelligent brother. He was exceptionally “silent, cunning, tireless, and resolute,” and known for his size and strength. Daniel was also a “born detective” who seldom failed in his work. Although he reveled in winning his “crude contests with fugitive slaves,” he was a mercenary at heart with no deep principles on the subject. Unlike his older brother, who would fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War, Daniel “did not believe that either slavery or freedom was worth dying for.” He was, however, always ready to collect the bounty on a fugitive or an occasional outlaw, whether his quarry were black or white. It was Cook’s miserable luck to walk from the forest into an open field in the borough of Mont Alto, where Daniel Logan was standing with a group of ironworkers from the nearby forge.

Cook was ready with the practiced story that he was a lost hunter in search of provisions. He should have known better than to step into the middle of a work party, but he had already hiked several miles and did not want to return without food. With typical nerve, and in this instance true carelessness, Cook approached the laborers and asked where he could “replenish his stock of bread and bacon.”

Daniel, however, was not as naive as the farmers the previous afternoon. Keenly aware of the value of the Harpers Ferry fugitives, Logan was well-informed and fearless. As he watched the ragged man step out of the woods, he whispered to ironworks manager Cleggett Fitzhugh, “That’s Captain Cook; we must arrest him; the reward is $1000.”

Slyly, Logan invited Cook to accompany him to a nearby—actually nonexistent—store for supplies. That was Cook’s last opportunity to run, but Logan had “disarmed suspicion…by his well-affected hospitality,” and Cook did not realize he was being flanked by two bounty hunters. With Logan and Fitzhugh on either side, the unsuspecting Cook began to walk toward town, only to be roughly seized “and held…as in a vice,” unable to reach his pistol. After a brief and hopeless struggle, Cook was overpowered.

“Why do you arrest me?” he asked.

“Because you are Captain Cook,” said Logan.

Cook was taken to Fitzhugh’s home, where he was “stripped of his weapons” and given a cold meal. A search turned up several incriminating documents, including a printed commission, marked No. 4, as a captain under Brown’s “Provisional Government” that left no doubt about his identity:

HEAD QUARTERS—WAR DEPARTMENT

Near Harpers Ferry, Md Whereas: John E. Cook has been nominated a captain in the Armory established under the provisional government. Now, Therefore, in pursuance of the authority vested in us by said Constitution, we do hereby appoint and commission said John E. Cook, captain.

Given at the office of the Secretary of War, this day, October 15th, 1859.

John Brown, Commander in Chief

H. Kagi, Secretary of War

The bounty hunters also found two receipts in Cook’s pocketbook, both bearing his signature in a “bold, legible hand.” Equally damning, although more circumstantial, was a small piece of parchment with a string tied on one end, with the handwritten inscription:

One of a pair of pistols presented by Gen. Lafayette to Gen. Washington, and worn by Gen. W. during the Revolution—descended to Judge Washington, and by him bequeathed to George C. Washington, and by him to Lewis W. Washington, 1854.

That was not quite the smoking gun itself, which Cook had left in a carpetbag on the mountain, but it was certainly enough evidence to claim Governor Wise’s reward. Cook was bundled into Fitzhugh’s open buggy for the trip to Chambersburg.

Capture by Daniel Logan was the beginning of the end for Cook. Despite several attempts to escape execution—including the notorious confession that earned him the ire of John Brown, the other conspirators and their supporters, Cook was convicted of insurrection and murder in the Harpers Ferry raid and hanged on December 16, 1859. Tidd, Merriam, Coppoc and Owen Brown were never captured. All but Owen Brown later served in the Union Army.

Adapted from John Brown’s Spy: The Adventurous Life and Tragic Confession of John E. Cook by Steven Lubet (Yale University Press, 2012).

Originally published in the January 2013 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.