‘[Larn] and Selman claimed that those cowboys made a fight and would not surrender,’ said Drew Taylor. ‘They did not give those cowboys a dog’s chance’

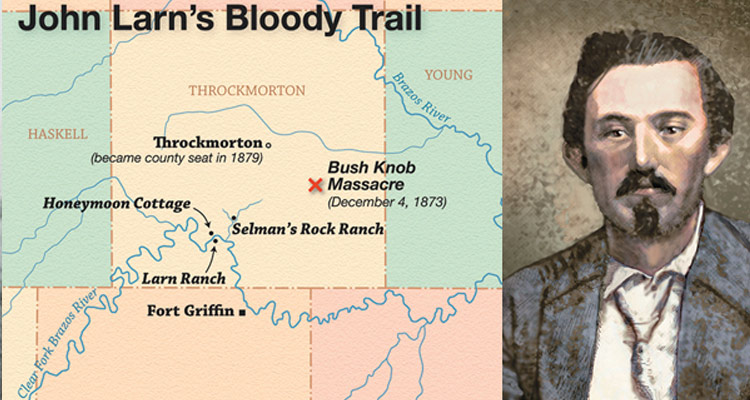

On December 4, 1873, a posse brutally gunned down eight cattlemen on a grassy plain near Bush Knob Creek in Throckmorton County, Texas, which the state Legislature had established 15 years earlier but would not be officially organized until 1879. Exact details about the deadly incident remain sketchy, but it has come to be called the Bush Knob Massacre. No Indians were involved in the massacre. It was a cowboy vs. cowboy affair, with buffalo soldiers participating on one side. The killings were the culmination of a series of events beginning more than two years before and were the end result of greed on the part of the violence-prone principal parties in the tragedy—killers and victims both. Looming larger than the rest of the participants was John Larn, a charismatic if enigmatic young man who had drifted into Texas from Alabama around 1867 and soon began a short, eventful, violent career on the ranges of the Clear Fork of the Brazos River near Fort Griffin. Also involved was John Selman, who would gain notoriety years later for killing one of the West’s most notorious gunmen, John Wesley Hardin, in an El Paso saloon.

In the summer of 1871 William J. “Bill” Hayes, a rancher in the Fort Griffin district, had decided to mount a cattle drive to the developing market in Trinidad, Colorado Territory, where prices for beef cattle were on the rise. After the fall roundup he put together a mixed herd of about 1,700 head. Some were his animals, and some belonged to other cattlemen who had turned them over to Hayes to sell. As trail boss for the drive he hired John Larn, who was only 22 but had already been up the trail to Colorado and had a reputation as a tough, determined herder who knew how to handle both wild Texas Longhorns and equally wild Texas cowboys.

The hands riding with him were a mixed bag that included hardened desperadoes, experienced trail drivers and wide-eyed greenhorns. For his right-hand man Larn chose Delbert C. Clement (aka Bill Bush), a self-proclaimed desperado with a notch-handled pistol who bragged of killings he had made. Other desperado types on the drive were Charlie Wilson, Frank Freeman, Bill Hill and Tom Atwell. Wilson was the most experienced drover, having been with the outfit of legendary Texas cattlemen Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, who had blazed the trail to Colorado only five years earlier and traversed it several times since. Two others named Wilson, Billie and Jim, were on the drive, but none of the Wilsons were related. John Pettigrew cooked and drove the chuck wagon. Rounding out the crew were youngsters Albert Shappell, Font Twombly, and 20-year-old Henry Comstock, to whom we owe a debt of gratitude for writing a memoir of that trail drive many years later.

Hayes did not accompany his drovers to Colorado but instead traveled by stagecoach to Trinidad to negotiate with cattle buyers a price for his cattle before Larn arrived with the herd. Episodes of violence marked the drive, as Larn and his lieutenant Bush murdered several innocent Mexicans they encountered, and Bush shot and killed young Billie Wilson over a minor disagreement.

One day in late October as the drovers moved northward through New Mexico Territory, they met up with their employer Hayes, who had driven a wagon down from Colorado Territory with supplies and brought fresh horses. Together they moved the herd up through the Raton Pass to Trinidad. While they tended the herd waiting for Hayes to negotiate a favorable sales price, Bush continued his reckless ways, stealing a valuable racehorse from a stable and riding it up into the mountains. Pursued by lawmen, he eventually returned the animal to its stable but left a written warning for the officers, threatening their lives should they attempt to arrest him. Then, in early February 1872, a wild shootout erupted in the Exchange, a Trinidad gambling hall and saloon, in which members of the Hayes crew shot and killed Juan Cristobal Tafoya, sheriff of Las Animas County. Other officers chased the cowboys back to camp but, when confronted by an array of Winchester rifles, withdrew without making arrests.

When Hayes continued to have difficulty disposing of his herd at a favorable price, his trail crew drifted off. Larn, accompanied by Atwell, returned to Fort Griffin, carrying with him a power of attorney given him by Hayes. This paper authorized Larn to manage Hayes’ remaining cattle in Shackelford County until the cattleman’s return.

Back in Texas, Larn cemented his standing in the Clear Fork country on November 28, 1872, by marrying Mary Jane Matthews, the pretty 15-year-old daughter of Joseph Beck Matthews, a pioneer rancher and one of the most respected men in Shackelford County. As a wedding present Joe Matthews gave 500 head of cattle to augment Larn’s grazing herd. Using the stones of a deserted military post commanded by a U.S. Army lieutenant colonel named Robert E. Lee in 1856 and ’57, Larn built a three-room ranch house dubbed the “Honeymoon Cottage.” He would later design and erect a six-room L-shaped stone house across the Clear Fork from the cottage, a home so well constructed that it has remained continually occupied to the present.

Following his return to Texas, Larn teamed up with John Selman, with whom he had first become acquainted in New Mexico Territory. The two would become fast friends and partners in a succession of criminal enterprises, the first of which was the treacherous theft of the Hayes cattle. When Bill Hayes finally disposed of his herd in the summer of 1873 and returned, he was shocked to find that Larn had betrayed his trust and used his power of attorney to integrate most of Hayes’ remaining cattle into his own herd. Although outraged and furious, Hayes held no claim as a gunman and was unwilling to confront Larn, a man reputed to be a cold-blooded killer, quick on the trigger. He chose instead to fight fire with fire.

Obtaining a contract to deliver 1,000 head of cattle to the reservation agency at Fort Sill in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in late fall, Bill and his brother John hired a crew of trail hands, instructing them to throw together a herd grazing on the Schackelford County rangeland and to not be particularly careful with regard to Larn or Selman brands, as they were probably rebranded Hayes Longhorns anyway. The crew, together with the Hayes brothers, was then to drive the herd up into the Nations. Bill Bush, the desperado who had been Larn’s right-hand man in the drive to Trinidad, headed up the Hayes’ recruits. Other hired hands were John Webb, George Snow, Guy “Jesse James” Jeames, Webster Hazlett and Doc Hearn. Reportedly due to his history of misfortune Hearn had been tagged with the appellation “Hard Times.” But this term might well have been applied to all who set out on this drive, as all eight would become victims in the Bush Knob Massacre.

When John Larn learned of Bill Hayes’ intentions, he enlisted the aid of neighboring rancher G. Riley Carter, who held a commission as constable under Sheriff John H. Caruthers of Palo Pinto County, to which the as yet unincorporated counties of Shackelford, Throckmorton and others were attached for purposes of law enforcement. With the help of Carter, Larn obtained a warrant for Hayes’ arrest on a charge of rustling. Assembling a posse that included John Selman and his brother “Tom Cat” and a cattle inspector named Beard, Larn and Carter called on Lt. Col. George P. Buell, commander of the garrison at Fort Griffin, and requested the assistance of troops to pursue the Hayes bunch. Buell ordered 2nd Lt. Edward P. Turner of Troop B, 10th Cavalry, to lead a detachment that would provide assistance in serving the warrant. The civilian posse and a detail of 17 black cavalrymen, the celebrated buffalo soldiers, set out on December 3 in pursuit of the Hayes outfit.

The next morning as they approached a stream called Bush Knob Creek in south-central Throckmorton County, Drew Kirksey Taylor, a young line-rider for the Browning brothers’ ranch, caught sight of them. “I was just a boy then, but I remember the incident quite clearly,” he later wrote.

[I] saw a party of men at a distance, and at first I was not sure whether they were Indians or white men. I stopped for a while and looked at them, and as they did not ride like Indians, I decided they were soldiers. I then galloped my horse around a bunch of cattle I was driving, and was riding west, when suddenly they started on a run toward me. I then stopped and waited until they came up. And as they approached, I heard one of them say, “Oh, that’s just a boy.” They rode up, and one of them asked me if I knew of any cow outfit passing through or camped in that part of the country.

As a matter of fact, young Taylor replied, only that morning he had stopped at the camp of the Hayes brothers, who were resting a trail herd about six miles away. Unhesitatingly he gave them directions, and the pursuing party rode on. “I did not know then that I had given these inhuman brutes the information that led them to the camp where they brutally murdered unsuspecting and innocent men,” Taylor sadly recalled. “These Negro soldiers, headed by two white outlaws, one by the name of John Laren [sic] and the other named John Selman…followed the direction I had given them and located the camp of the Hayes outfit.”

Nearing the Hayes camp, members of the combined civilian-military posse dismounted and moved closer, using the banks of Bush Knob Creek as cover. There they spotted four men—Bill and John Hayes, Bill Bush and George Snow—eating their noon meal. The other four in the outfit—Jeames, Hearn, Webb and Hazlett—were tending the herd.

Descriptions of what then transpired are confusing and contradictory. The only known account by an actual eyewitness was Lieutenant Turner’s official report to his superiors. He said that when the four men in camp spotted the posse they reached for their weapons and began firing. In the answering rifle barrage, two were killed instantly, while the other two were shot as they tried to escape.

An account of the affair in The Galveston Daily News was more detailed and quite different. According to this version an attempt was made to take all four men into custody, but only two submitted to arrest, “and the other two resisted by firing their revolvers at the constable’s party. At the time the firing commenced, the two who were in arrest attempted to escape, one of them grasping a carbine belonging to a member of the guard, and the four were instantly shot and killed.”

The young cowboy Drew Taylor said the posse opened fire without warning, killing all four. “I was one of the men who helped to bury those unfortunate cowboys, and when I say it was diabolical murder, I know whereof I speak.”

Although he was not there, Henry Comstock’s prior experience with several of the principals involved provided him special insight into what took place. “As I picture it, knowing the men as I know them, I would say that Laren [sic] killed Bush first and Hayes next and possibly one or two of the others. Bush [was] known by Laren as the dangerous one, and Hayes because he was in Laren’s way.”

Their bloody work finished at the camp, the deadly pursuers rode after the remaining members of the Hayes outfit. Larn, Selman and the others found Jeames, Hearn, Webb and Hazlett and arrested them without incident. Larn then directed some of his followers to turn the herd back toward Shackelford County. That night the rest of Larn’s group shot the remaining members of the Hayes party. Again accounts of how that happened are vague and contradictory. In his official report Lieutenant Turner stated the four attempted to escape, and guards shot them down. The Galveston Daily News repeated his version.

In his memoirs Richard Henry Pratt, then a 10th Cavalry lieutenant at Fort Griffin and later founder of the famed Carlisle Indian Industrial School, recalled the affair, but his version is filled with inaccuracies. As he remembered it, the posse trailed a party of “horse and cattle thieves…to their rendezvous well out in the buffalo region,” where they found two corrals on a creek, with “five white men at one and four at the other and nearly a thousand cattle and about forty horses between them.” The posse captured both outfits “without firing a gun…[but] during the night the prisoners had tried to get away, and all were shot to death.” It was the position of the civilian posse members, Pratt said, “that stock stealing along the border was so common that it was impossible to get a clean jury against it, and the best way to end it was to end the thieves when caught.”

While acknowledging that eight men had died violently at Bush Knob, military and civilian officials alike merely shrugged. Others, however, roundly condemned the slayings as cold-blooded murder. “Laren and Selman claimed that those cowboys made a fight and would not surrender, and that they had to kill them in self-defense, which was not true,” said Taylor. “They did not give those cowboys a dog’s chance.”

Comstock, knowing Larn well, said he had no doubt “but that Laren killed the four prisoners, because I heard Laren say many times that dead men tell no tales.” The posse burned the saddles of the four men, he said, a good indication the killers had shot their victims in the head while they slept, cowboy fashion, using their saddles as pillows.

Some newspaper accounts treated the affair as a wild tale of frontier warfare. The Fort Worth Democrat, for instance, reprinted a highly inaccurate story taken from the December 15 issue of a Weatherford paper. The article described the shooting as a gun battle at the “James’ Ranche [sic] on the Clear Fork of the Brazos, six miles below Fort Griffin.” Owned by an “old man James,” the place was said to be “surrounded by the worst set of desperadoes and cattle thieves” infesting the country. Determined to drive them out, a bunch of enraged citizens, supported by troops from Fort Griffin, closed in on the outlaw stronghold, or so the story went. It continued:

Upon arriving at James’ Ranche, they were immediately fired upon by about twenty-five of the desperadoes, all armed to the hilt with Henry rifles and two six-shooters each. The detachment immediately charged the ranche, keeping up a hot fire all the time, and as the house was rather open, the bullets induced the outlaws to retreat.…As they left the house, [they] were shot down by the frontiersmen that accompanied the troops.…The killed were Wm. Hayes, Geo. Snow, “Doc” Hern, “Gov.” James, “Hard Times,” and Wm. Bush. The remainder of the party escaped, none seriously wounded except “old man James”—he was noticed to mount his horse with great difficulty. This virtually broke up the worst nest of desperadoes on the Texas frontier, and one that has been the cause of all the horrible murders that have been committed in the vicinity of Fort Griffin for the past four years.

There was, of course, no “old man James” who owned a ranch near Fort Griffin. One of the Bush Knob victims, young Guy Jeames ( “Gov.” James in the Weatherford report), was the son of a widow who lived near Fort Griffin, according to Taylor. Quite possibly Larn and followers concocted this specious story to recast the cold-blooded reality of the Bush Knob killings into a tale of frontier heroism.

On rangeland near Fort Griffin local ranchers held the Hayes brothers’ captured herd for inspection to retrieve stolen Longhorns, with Larn heading the list of claimants. There was no inquiry into the eight deaths at Bush Knob. As Taylor recalled, “In that day and time there was not very much said and nothing done in the way of prosecution with regard to anyone found dead.”

John Larn went on to become sheriff of Shackelford County in 1876, but his increasingly bold criminal acts led to his violent death five years after the Bush Knob killings. In the early hours of June 24, 1878, as Larn sat under arrest and in irons in the county jail at Albany, a band of vigilantes broke into the jail and riddled him with bullets. His partner in crime, the wily John Selman, avoided a similar fate for 18 more years, but his violent career, capped by his murder of Hardin in El Paso’s Acme Saloon on August 19, 1895, ended abruptly on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1896, when Deputy U.S. Marshal George Scarborough shot him dead in an El Paso alley.

R.K. DeArment is a frequent contributor to Wild West and the author of many books about outlaws and lawmen, including Bravo of the Brazos: John Larn of Fort Griffin, Texas, which is recommended for further reading along with A Texas Frontier: The Clear Fork Country and Fort Griffin, 1849–1887, by Ty Cashion, and The Frontier World of Fort Griffin: The Life and Death of a Western Town, by Charles M. Robinson III.