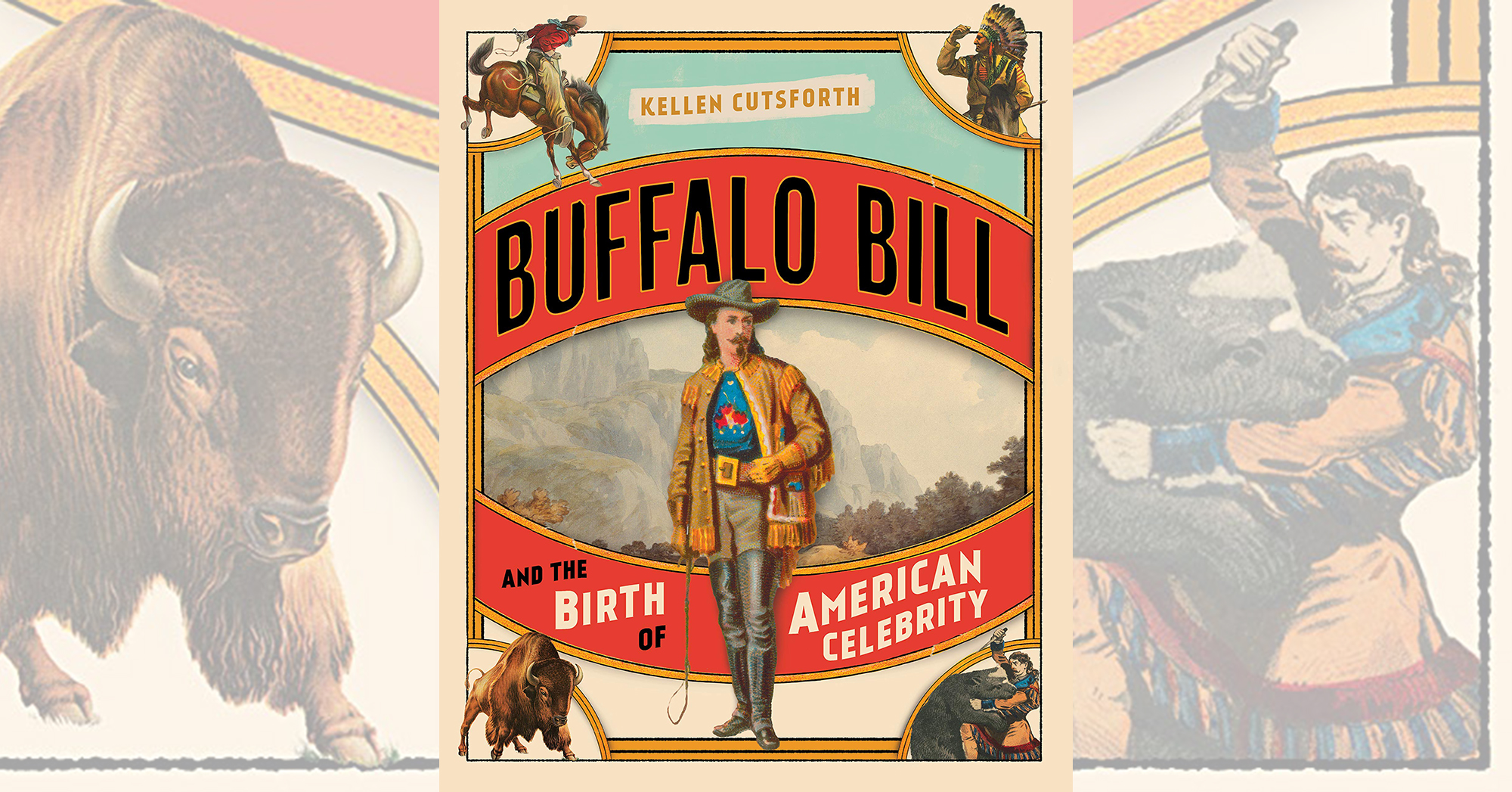

Buffalo Bill and the Birth of American Celebrity, by Kellen Cutsforth, Two Dot, Guilford, Conn., Helena, Mont., 2021, $29.95

Even after taking the trouble to take acting lessons, William Frederick Cody’s thespian talents were barely passable at best. When he launched his “Old Glory Blowout” on July 4, 1882, however, that handicap was meaningless. Endowed with affability and charisma, combined with being a bona fide hero of the formative days of the American West, “Buffalo Bill” didn’t need Edwin Booth’s flair for the theatric. To lift an appropriate phrase from Irving Berlin’s 1946 musical Annie Get Your Gun, Bill could sell himself and his outdoor extravaganza just by “Doin’ What Comes Natur’lly.”

Even with that raw material, however, there was influence, inspiration, perspiration and evolution behind what became Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. In Buffalo Bill and the Birth of American Celebrity Western writer and unapologetic Buffalo Bill fan Kellen Cutsforth conveys the reader along a profusely illustrated path to re-create the process that created the nation’s—and perhaps the world’s—first superstar.

“In the case of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, the aspects of frontier life it embodied were nearly foreign concepts to the crowds who watched the circuslike spectacle,” Cutsforth writes in his first chapter, titled “Every Idea Is Inspired. “The show consisted of reenactments of historic battles combined with displays of showmanship, sharpshooting, buffalo hunts, horse racing and rodeo-style events. Each show was three to four hours in length and began with a parade on horseback. The parade was a major ordeal—an affair that involved huge public crowds and multiple performers. Not too entirely different from the parades currently held at Walt Disney’s numerous theme parks every night.”

Among Cody’s earliest influences, of course, was Phineas T. Barnum, whose collection of museums and freak shows under a single tent combined whatever he could find with whatever he could conjure up. This came to include American Indians, walking exhibitions whom he treated with undisguised contempt. “P.T.’s use of native peoples in his exhibitions was often one of exploitation,” writes Cutsforth. “He paid the Indians poorly, treated them as savage brutes and only used them to make a quick buck. In what was perhaps a deserving end for the business and indicative of his exploitive ways, in 1865 Barnum’s American Museum burned to the ground.”

In contrast, Buffalo Bill genuinely and seriously believed he was edifying his audience on a rapidly vanishing era. It it is no coincidence he never used the term “show” for his extravaganzas. He treated his Indians with dignity and equitable pay. For instance, writes Cutsforth, “In addition to his weekly salary and bonuses, Sitting Bull had a clause written into his contract allowing him to sell autographs and his portrait while keeping all the proceeds.”

Cody also treated Annie Oakley and his other female employees well. “With Oakley’s stage presence and ability to draw large crowds wherever she went, Buffalo Bill paid her like the star she was,” writes Cutsforth. “In fact Bill paid most of his female performers just as well as his male stars. Referring to this subject, Bill was quoted as saying, ‘What we want to do is give women even more liberty than they have. Let them do any kind of work they see fit, and if they do it as well as men, give them the same pay.’” That said, Cody might have showed his “showgirls” a little too much attention at times to the annoyance of his wife, Louisa.

As for the hokum the dime novels presented alongside his Wild West, Cody was aware of and willing to exploit the exaggerations, secure in knowing his exploits as Pony Express rider, Army scout and frontier hero were built around a kernel of truth. For the audience, seeing Buffalo Bill was, as the author expresses it, like a later generation meeting Superman…except this hero was for real.

Cutsforth concedes Cody had his human flaws—he was not the best of family men, and his lack of management skills proved a fatal weakness on more than one occasion. Ultimately, however, this unabashed hagiography concludes Buffalo Bill laid the groundwork for all the celebrities that followed, as well as the superhero comic book (or “graphic novel”), cinematic and television Westerns and, for that matter, the still-recurring concept of the American West itself.

—Jon Guttman

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.