Many years later, a former soldier of the 11th Kansas Cavalry tried to explain the reasons for the Indian War of 1865. Sergeant Stephen Fairfield remembered that whites had previously found gold and silver in the mountains beyond the Great Plains and that thousands of miners had bolted through Indian country, killing and destroying the game. ‘Long trains of wagons were winding their way over the plains;’ he wrote, ‘the mysterious telegraph wires were stretching across their hunting grounds to the mountains, engineers were surveying a route for a track for the iron horse, and all without saying as much as `By your leave’ to the Indians. Knowing that their game would soon be gone, that their hunting grounds taken from them, and that they themselves would soon be without a country, they had resorted to arms to defend their way of life and themselves.’

There were more specific reasons, however. Beginning in April 1864, a series of incidents between Plains Indians (mostly Cheyennes and Sioux) and white emigrants, traders and military patrols had elevated intermittent violence into a reign of death and destruction. The climax of killing in 1864 came on November 28, when Colonel John Chivington led his 3rd Volunteer Cavalry in a dawn raid on the Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos camped on Sand Creek in west-central Colorado Territory. Believing themselves under the protection of Fort Lyon, the Indians were unprepared and completely surprised. At least 130 of them died.

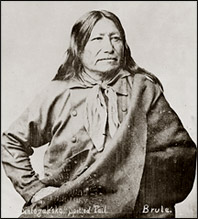

At the Cheyenne camp on Smoky Hill, survivors gathered in council. They decided to ask nearby allies to join with them in a war of vengeance. Invitations went to the Northern Arapaho camp and to Sioux groups living on the Solomon Fork. A large village soon assembled. Leading the Cheyennes were Leg-in-the-Water, Little Robe and a reluctant Black Kettle. Foremost among the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, who assumed a leadership role, were Tall Bull, White Horse and Bull Bear. The half-Cheyenne sons of William Bent, George and Charles, pledged their support. Joining the coalition were Northern Arapahos under Little Raven, Storm and Big Mouth. Finally came Pawnee Killer’s Oglalas and Spotted Tail’s Brulé Sioux. At the same time, messengers journeyed north to the headwaters of the Powder River to tell the Oglala, Minneconjou and Sans Arcs Sioux and the Northern Cheyennes of the killing. These groups later joined their tribesmen in one last united campaign.

Library of Congress |

| Spotted Tail, who showed much martial prowess in his younger days, was a highly respected peace chief by the 1860s, but he was not destined to die peacefully. |

At this time, Spotted Tail was 41 years old, a veteran of the Grattan Fight against U.S. troops in 1854 and the Battle of Blue Water Creek against Brevet Brig. Gen. William Harney’s forces in 1855. He had been in a military prison for a year, after having surrendered for participating in the killing of three stagecoach employees. He was a practiced and fearless fighter who had counted many coups. Knowing the white world better than his contemporaries, he was aware of the might of his enemies.

Retribution began on January 7, 1865, with an attack on Julesburg, Colorado Territory, where the combined Indian force killed four noncommissioned officers and 11 enlisted men of the 7th Iowa Volunteer Cavalry, stationed at nearby Fort Rankin. On February 2, they returned to loot and burn the settlement, keeping the 7th Iowa troops confined in their post. Troops under William O. Collins, regimental leader of the 11th Ohio Cavalry headquartered at Fort Laramie, hurried east to engage the raiders. They clashed at Mud Springs and Rush Creek, in western Nebraska, on February 4-6 and February 9, as the warriors had begun to move north and west to join their tribesmen in the Powder River country of Wyoming and Montana. Casualties were light on both sides, but the overwhelming strength of the Sioux and Cheyennes made pursuit impractical.

At this point, Spotted Tail and his followers decided to leave the coalition. They had done their part, and they were reluctant to leave the country where they had lived for many years. In a short time, they declared themselves friendly and went into camp near Fort Laramie, intending to distance themselves from the war that would continue when the southern tribes reunited with their northern counterparts.

By early June, about 1,500 friendly Indians camped near Fort Laramie, including Spotted Tail and the Southern Brulés. Military leaders decided to send them to Fort Kearny, where they would be away from the war zone and could plant a crop to provide temporary sustenance. On June 11, the friendlies and a number of white traders with their mixed-blood progeny left the post with an escort of about 22 7th Iowa Cavalry and Indian police commanded by Captain William Fouts.

The night of June 13 found the travelers camped on Horse Creek, near the site of the Fort Laramie Treaty Council of 1851. At a clandestine meeting held that night, most of the chiefs and headmen decided that they would rather suffer death than live in a starving condition at Fort Kearny, close to their Pawnee enemies. When troops marched out the next day, the Sioux remained in camp. Returning to investigate, Fouts found an argument in progress between peace and war factions. Suddenly, the Brulé Chief White Thunder turned and fired his rifle at the unlucky commander. In the ambuscade that followed, one bullet pierced Fouts’ heart and another entered his head. All of the remaining Sioux, including the Indian police, left in a hurry, fleeing north. During the next months, Spotted Tail and his followers stayed far away from the whites, camping on the upper reaches of the Powder River, about 260 miles north of Fort Laramie.

The Indian War of 1865 began to draw to a close in September.

In late July Brig. Gen. Patrick E. Connor’s retaliatory Powder River Expedition had traveled north to chastise the Sioux, Cheyennes and Arapahos for the killing of young Lieutenant Caspar Collins and 28 men in the Battles of Platte Bridge and Red Buttes. On August 29, Connor’s main column struck a large Arapaho village on the Tongue River, killing 63 Indians, burning 250 lodges, capturing 500 ponies, and burning tons of dried food and other supplies. At the same time, Connor’s other two columns ran into trouble in Montana, losing hundreds of horses while skirmishing with large parties of coalition warriors. When Connor was recalled a few weeks later, the expedition disbanded, presumed to be a failure.

The winter that followed was one of the severest ever known in the region, and it brought the Indian War of 1865 to an end. Some of the Sioux began coming in for peace talks in March, their women, children and elderly sick and hungry. To survive the terrible winter, they had killed and eaten most of their ponies. As Spotted Tail put it: ‘Our hearts were on the ground, my brother….If we had to swim through the snow, we would have come.’ In the chief’s case, there was an additional reason: Colonel Henry Maynadier, who commanded the West Sub-District of Nebraska from Fort Laramie, had received a message from Spotted Tail telling him that he wanted to bring the body of his deceased daughter to the post for burial. Some believed that the young woman had contracted consumption, but Maynadier speculated that exposure and the Indians’ hard life were the reasons for her death. The chief had picked an opportune time, for the ranking officer at Fort Laramie was a man of varied experience and tact, ideally suited to the situation. Born in 1830, Maynadier had graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1851. He had served initially with the 1st U.S. Artillery, then switched to the 10th Infantry, where he fought at Vicksburg and Fredericksburg. Becoming a major in the 12th Infantry on November 4, 1863, he received a number of special assignments for the next 16 months, including a stint in the Office of the Adjutant General in Washington. He became colonel of the 5th U.S. Volunteers on March 27, 1865. Maynadier had received the brevet rank of major general of volunteers on March 13, 1865, for distinguished service on the frontier in operations against hostile Indians and accomplishing much toward bringing about peace with warring tribes. The post commander at the time was Major George M. O’Brien. Born in Ireland, O’Brien entered the Volunteer service as a major of the 7th Iowa Cavalry on July 13, 1863.

Spotted Tail’s daughter had spent some time around Fort Laramie and become fascinated with white ways. She may, in fact, have lived at Fort Laramie with relatives while her father was in prison in 1855-56. Known as Mini-Aku (Brings Water), she had been born in 1848, making her about 18 years old. She was the eldest daughter of the first of Spotted Tail’s three wives and his favorite. A small, delicate, comely, high-spirited girl, some said that she had fallen in love with an officer, perhaps from a distance. Her final wish was that her last resting place be in the post cemetery, near the burial of Old Smoke, a relative and chief who had lived near Fort Laramie for many years as a friend of the whites. Maynadier remembered the girl, whom he had met some five years before when she was about 12 years old, and he welcomed the chief’s coming.

On March 8, 1866, Maynadier and several officers, accompanied by a flagman, rode forth to meet the incoming chief and his party, numbering about 40 lodges. They had traveled the distance in 15 days. At the post, the colonel opened the council with words of condolence and welcome. In a conciliatory manner, he pointed to the American flag, saying: ‘You see a red stripe and a white stripe side by side, and they do not interfere with one another. So the red man and the white may live in this country in harmony.’ He then asked if Spotted Tail wished to have his daughter placed in the cemetery and Christian rites performed. The chief assented in a speech of great eloquence and feeling, shedding tears as he spoke.

Wrapped in buffalo robes and bound with cords, the girl’s body lay in state in a room in ‘Old Bedlam,’ the ranking officer’s office and living quarters. Hastily arranged muskets, sabers and flags decorated the walls. Maynadier instructed his carpenters to have a coffin made, and post trader Colonel William G. Bullock donated a fine red cloth to cover it. Maynadier suggested a sunset burial, telling Spotted Tail that ‘as the sun went down it might remind him of the darkness left in his lodge when his beloved daughter was taken away, but as the sun would surely rise again, so she would rise, and some day we would all meet in the land of the Great Spirit.’ Tears appeared again on the chief’s cheeks as Maynadier spoke.

The officer also told Spotted Tail that in two or three months peace commissioners would come to Fort Laramie to meet with him and other tribal leaders. According to Maynadier, the chief responded as follows:

There must be a dream for me to be in such a fine room, and surrounded by such as you. Have I been asleep during the last four years of hardship and trial, and am dreaming that all is to be well again, or is this real? Yes, I see that it is, the beautiful day, the sky blue and without a cloud, the wind calm and still, suit the errand I come on, and remind me that you have offered me peace. We think we have been much wronged and are entitled to compensation for the damage and distress caused by making so many roads through our country and driving off and destroying buffalo and game. My heart is very sad, and I cannot talk on business. I will wait and see the counselors the Great White Father will send.

About 200 yards to the north of the post, soldiers built a scaffold to hold the coffin. The platform was about eight feet above the ground. At sunset of a bright and clear but bitterly cold day, the procession got underway. An ambulance transported the coffin to the burial site, located inside the fenced post cemetery. A 12-pound mountain howitzer followed the funeral conveyance, with the husky postilion resplendent in red chevrons. Then came the 200 Indians in Spotted Tail’s train and most of the 600 men of the garrison who were not on duty, all marching to the solemn music of the post band. The Brulés killed two white ponies, nailing the heads by their ears to the posts, facing toward the rising sun. Below the heads were containers of water for the animals to drink as they conveyed the girl to the spirit land. Soldiers formed a large square around the site, while Indians formed a circle around the crypt.

Officers placed the girl in the open coffin. Colonel Maynadier contributed a pair of gauntlets, to keep Mini-Aku’s hands warm, while other officers added such items as moccasins, red flannel and clothes — all intended to keep the maiden comfortable on her journey. Major O’Brien put in a greenback so that she could buy what she wanted on her way to the spirit world. Each of the Indian women came forth, bearing some little gift, a string of beads, an embroidered pine cone, a small looking glass. Each whispered something to the deceased and then returned to her place. Finally, Spotted Tail gave a little red book to the post chaplain, the Rev. Alpha Wright. It was an Episcopal prayer book that Brevet Maj. Gen. William Harney had given the girl many years before. The chaplain placed it inside. Many hands raised the coffin to its resting place on the scaffold, with the head placed toward the east. Chaplain Wright then conducted services, improvising a sermon. He promised that the girl would look down and take care of her father, mother and friends, and that they would soon meet her where there was plenty of game and no more snowstorms, tears or dying. The mother of the dead girl wept deeply while the father-chief often wiped his eyes.

The result of the burial at Fort Laramie was the beginning of a trust between the officer and the Brulé leader. In ending a letter to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, written the day following the burial, Maynadier declared, ‘The occurrence of such an incident is regarded by the oldest settlers, men of most experience in Indian character, as unprecedented, and as calculated to secure a certain and lasting peace.’ Maynadier concluded that the chief would ‘not have confided the remains of his child to the care of any but those whom he intended to be friends always.’ The officer was correct; Spotted Tail never fought whites again. Perhaps it was as Colonel Henry Carrington later conjectured: ‘As his daughter was adopted by the white man’s Great Spirit, he had no heart to fight the white man any more.’

On March 12, Spotted Tail and Red Cloud approached Fort Laramie for a council. Maynadier and his officers went out to meet them near the crossing of the North Platte River two miles east of the post. There were about 200 warriors in the party, the Sioux drawn up in a line, singing and shouting. Besides the two chiefs were other prominent leaders, among them Standing Elk, Brave Bear and Trunk. Maynadier rode into Fort Laramie with Spotted Tail on one side and Red Cloud on the other, presenting as he put it, ‘a gay and novel appearance.’ In all, there were about 700 Brulés and Oglalas that camped nearby, the people described as being destitute of everything.

After hearing their grievances about whites entering their hunting grounds, their poverty and the difficult winter, Maynadier gave them the expected feast. Red Cloud stated that he wanted to meet the Great White Father, and the officer promised to explore the possibility. Swift Bear and 40 lodges arrived in the area on the same day that Maynadier met with Spotted Tail and Red Cloud. They camped near the trading house of Red Cloud’s brother-in-law James Bordeaux, nine miles east of Fort Laramie on the North Platte River.

With these events, prospects for peace on the Plains looked promising. The surrender and discussions with these bands of Sioux were auspicious beginnings for treaty negotiations that were slated for Fort Laramie on May 20. Red Cloud, the fabled Oglala chief who had counted 80 coups against his Indian enemies in war, was the key. Just emerging as a leader of the resistant Sioux in the southern half of the Northern Plains, he commanded respect. Blessed with a beautiful oratorical voice, his words complemented his deeds. While the Indian War of 1865 was over, it would be Red Cloud who determined whether there would be an Indian War of 1866, for Spotted Tail had made his peace forever. In 1868 Spotted Tail was one of many native leaders — Lakotas, Cheyennes, Arapahos and Crows — to sign the Fort Laramie Treaty, which, among many other things, called for an end to all war between the Plains tribes and the U.S. government and its citizens.

Over the years, legends grew about the Indian maiden, and different names surfaced. Colonel Maynadier in his accounts of the affair called her Ah-ho-ap-pa (‘Wheat Flower’) and then Hinziwin (‘Fallen Leaf’). Eugene Ware, who was the post adjutant at Fort Laramie when the funeral took place, also called her Ah-ho-ap-pa in a magazine article and in his book The Indian War of 1864, published in 1890. This became ‘Falling Leaf’ in other renditions by numerous authors. In 1867 Louis Simonin, a Parisian traveling the West, identified her as Moneka. A newspaper in 1902 identified her as Shunk-hee-zee-wah (‘The Girl that Owned the Yellow Mare’). A 1909 account named her ‘Fleet Foot,’ and it seems that her white acquaintances called her Monica when she was living at Fort Laramie. Other names included ‘Faded Flower,’ ‘White Flower’ and ‘Princess.’ And so it went, each new story adding embellishments and often new names for Spotted Tail’s famous daughter. In some stories Mini-Aku was having a secret affair with an officer who promised to marry her. When it did not work out, she died of a broken heart. Some identified the officer as Captain Levi Rienhart, of the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry, who died in an Indian fight west of Fort Laramie on February 13, 1865. One of the most intriguing stories is found in Carrie De Voe’s Legends of the Kaw, appearing in 1904. De Voe relates that Mini-Aku’s lover was Thomas Dorion, a military courier. He had been sent as a messenger of peace. Staying with the Brulés for a short time, he had fallen in love with the girl and desired to marry her, and she had expressed a willingness to become his wife. However, Mini-Aku grew ill and died before it happened.

During the 1880s a song written by some unknown Fort Laramie soldier kept the legend alive. Whenever men gathered to sing, ‘Fallen Leaf’ was sure to be heard. Johnny O’Brien, a son of a Fort Laramie enlisted man, remembered the verses even when he was 90 years old:

Far beyond the rolling prairies

Where the noble forest lies

Dwelled the fairest Indian maiden

Ever seen by mortal eyes.

And her eyes were like the sunset

Daughter of an Indian Chief

Came to brighten life in autumn

So they called her Fallen Leaf.

Fallen Leaf the breezes whisper

Of thy spirit’s early flight,

And within that lonely wigwam

There’s a wail of woe tonight

Through a long and tangled forest

All upon a summer’s day

Came a hunter weak and weary

From his long and lonely way.

Weeks went by but still he lingered.

Fallen Leaf was by his side.

And with love she smiled upon him

Soon to be his woodland bride

One bright day this hunter wandered

Through the prairie all alone.

Fallen Leaf she watched and waited

But his fate was never known.

On a summer’s day she fainted.

In the autumn leaves she died,

And they closed her eyes in slumber

Near the Laramie riverside.

Mini-Aku was indeed a tragic figure, with hopes unfulfilled and dreams that never came to be.

This article was written by John D. McDermot and originally appeared in the February 2006 issue of Wild West.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!