Seven and a half hours into their training mission, Maj. Howard Richardson and his Boeing B-47B Stratojet flight crew finally began to relax after an evening of deploying electronic countermeasures and chaff to evade prowling North American F-86 fighters. The sky was clear and full moonlit. Heading south at 35,000 feet and 495 mph over Hampton County, South Carolina, their next stop was home.

Suddenly, without warning, a massive jolt yawed their aircraft to the left, accompanied by a bright flash and ball of fire off their starboard wing.

The three airmen assumed they had been struck by something, but observed nothing. Training and experience took over as Richardson delicately descended his bomber to 20,000 feet to assess the damage and stability of the aircraft. At the far edge of the right wing, the crew could clearly see the No. 6 jet engine pointing upward at a 45-degree angle and strips of metal extending off the normally smooth aluminum-clad wing. The starboard wing external fuel tank was gone.

Richardson ordered his crew to prepare to eject as he pushed the fire shutoff switch to cut fuel to the still-thrusting engine, which was now nudging the aircraft into a left roll. His copilot, seated directly behind him, transmitted mayday alerts over the UHF Guard Channel. Richardson reduced his speed to 240 mph, extended the landing gear and wing flaps, and found that he could control the bomber. To trim it correctly he soon dropped the 1,780-gallon port wing tank after his navigator confirmed they were over an unpopulated area. With a barely flyable aircraft, Richardson soon realized he needed to lighten his load to increase his chances of landing safely. That load was an almost 4-ton hydrogen bomb. Thus began what is to this day one of the most controversial U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command “broken arrow” events of the Cold War.

The Nuclear Fleet

During the late 1950s, SAC worked diligently to improve its ability to quickly deploy strategic bombers and accurately deliver nuclear weapons onto target. To train aircrews for that role, SAC conducted Simulated Combat Missions, or SIMCOMs, during which B-47 crews would typically carry unarmed nuclear weapons and perform electronic bombing, radioing the data back to ground stations for accuracy scoring. The onboard weapons served to give the flight crews the most realistic weight and handling experiences in case they ever had to respond to an actual Soviet attack.

By 1954, SAC could deliver a “Sunday punch” of 750 strategic bombs from a combination of B-36s, B-47s and B-50s stationed in the U.S., Britain and elsewhere. Not long after, SAC implemented a 24-hour alert program for its strategic bomber force. Beginning in 1955, selected bomb wings had their B-47s and KC-97 aerial refueling tankers armed, fueled and parked on the runway, ready to go.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Just an Exercise

Midafternoon on February 4, 1958, Maj Richardson began to prepare his B-47B-50-BW serial no. 51-2349A and crew for a SIMCOM, codenamed Operation Southern Belle. A member of the 19th Bombardment Wing, 30th Bombardment Group, at Homestead Air Force Base in Southern Florida, Richardson was an experienced B-47 command pilot and flight instructor with more than 1,800 hours on this type. His aircraft had been upgraded the prior October to the same configuration as the newer E model, part of an extensive modification program to remove alarming structural and safety weaknesses in the B-model fleet. Co-pilot 1st Lt. Robert J. Lagerstrom and radar-navigator/bombardier Captain Leland W. Woolard accompanied him as the ground crew prepared their 95-ton combat-weight aircraft, call sign Ivory II. A second B-47, Ivory I, would join them that night, forming the Ivory Cell. In the bomber’s nose beneath the cockpit, Woolard would focus his attention that night on the AN/APS-64 search radar and accompanying scopes to accurately deliver the electronic “bomb.”

The nuclear weapon specialists from the Homestead aviation depot squadron prepped Ivory II’s thermonuclear payload at its munitions storage area. There they informed Richardson that his bomb was transportation-configured and thus contained no uranium pit, or capsule, which would have been required for a nuclear detonation.

In the video documentary “America’s Lost H-Bomb,” Richardson recounted: “Before takeoff you would go down to the munitions center and you would sign a document signing for the weapon. And it would give the serial number identification of the weapon and what aircraft it was loaded on board and who its aircraft commander was, and that’s where I signed my name.”

That document, an Atomic Energy Commission to Air Force “Temporary Custodian Receipt [for maneuvers],” stated that the signatory “will allow no assembly or disassembly of this item while in my custody, nor will I allow any active capsule to be inserted into it at any time.”

The word “simulated” was scribbled on Line C, reportedly for the capsule. Some historians have interpreted this to mean that the bomb contained an inert lead ball in place of the nuclear pit. Armed only with .45-caliber pistols, the specialists towed the bomb from the storage area to the flight line at a crawling 5 mph.

THe BOMB

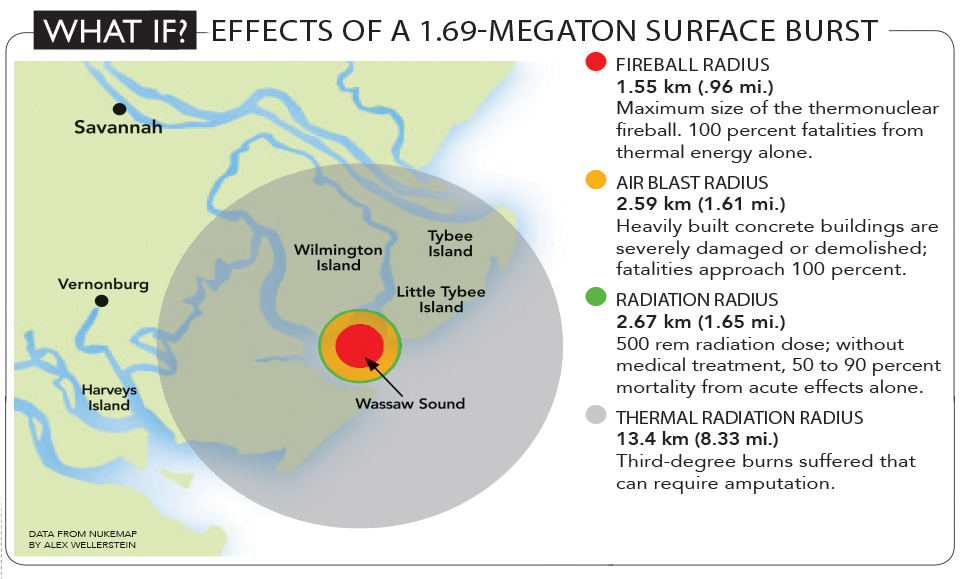

During the summer of 1955, SAC had begun to deploy the “lightweight” 1.69-megaton-yield Mark 15 Mod 0 hydrogen bomb, a blunt-nosed 7,600-pound beast that was about 11½ feet long and a little less than 3 feet in diameter. The 400 pounds of high explosive in the fission primary surrounded a 15-pound highly enriched uranium pit. If called upon, the crew would arm this “open-pit” weapon by activating the automatic inflight insertion system, a screw jack that pushed the capsule into the center of the explosive lenses. Otherwise, the capsule was accessible only by removing and replacing the parachute package in the rear of the bomb casing. In any case, the Mk. 15 filled most of the bomb bay, rendering it impossible for crew members to modify it in flight. Inflight insertion of the capsule was not planned for that night. The thermonuclear secondary contained about 165 pounds of highly enriched uranium, which would provide 80 percent of the bomb’s yield.

Richardson directed the loading of the Mk. 15 into the bomb bay. As aircraft commander, he had the final responsibility for ensuring the bomb was properly stowed and its monitoring, control and release systems were connected. Since this was a training flight, the weapon specialists did not hand over a separate capsule to the flight crew, which would normally have been encased in a metal cylinder called a birdcage.

“We didn’t carry a capsule on the plane,” Richardson later recounted.

At that time, President Dwight D. Eisenhower would not permit SAC bombers to carry fully armed nuclear weapons on training flights. SAC had yet to deploy “sealed pit” weapons, which precluded their removal from the primary.

PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE

At 4:51 p.m. that cool, crisp afternoon, Ivory Cell took off from Homestead and headed west over the Gulf of Mexico. After rendezvousing with a KC-97 Stratofreighter and topping off their fuel load, the two B-47s turned north, flew over New Orleans and headed for the Canadian border over Minnesota. With about 2,000 miles logged, they rolled back to the southeast toward the small town of Radford, Virginia, their simulated bombing target for the night. On the way, the crew practiced evading fighter interceptors by deploying electronic countermeasures and dispensing chaff to confuse radar.

Over Radford at 37,000 feet at 11:55 p.m., Woolard completed the electronic bomb drop (most likely targeting the Radford Arsenal), with the required signal transmitted to SAC leadership for evaluation. Although they spotted more interceptors in the distance, the crew were informed that the airspace south of Virginia was “friendly” and assumed their evasion exercises were finished for the night. Ivory I soon advanced about a mile ahead of Richardson’s Ivory II.

MIXED SIGNALS

To fend off any incoming Soviet bombers on the East Coast, Air Defense Command had established the 444th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron under the 35th Air Division at Charleston AFB in South Carolina in early 1954. ADC tasked pilots in F-86L Sabre Dog fighters with intercepting bombers on their training flights.

That night, they were not informed that the airspace south of Virginia was friendly territory. Three Sabre Dogs — some of the first deployed with the Hughes AN/APG-37 air-to-air radar and E-4 fire-control system — were fueled, armed and connected to engine start-up power carts for a rapid response.

First Lt. Clarence A. Stewart was one of the pilots waiting in the alert shack at the end of the runway when the horn went off at 12:08 a.m. Stewart strapped into his interceptor and climbed out five minutes later with his two wingmen. Radar crews at the 792nd Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron soon directed Stewart to intercept Ivory Cell and position his aircraft less than a mile above and about 15 miles behind Ivory II. In fighter pilot vernacular he called “Judy,” signaling that his quarry was in sight and he was now using his airborne radar to track and dive down to the bomber in a tail chase. With his face pressed against the hood of his radar scope, he steered a blip on the greenish-yellow radar screen toward the target.

But he was unaware that his radar had locked onto Ivory I, and he was descending unknowingly toward Ivory II. During the final seconds before the computed impact time of his simulated rocket attack, Stewart felt unusual turbulence buffeting his fighter, like the wash from a jet engine. At 12:33 a.m., he momentarily looked up from his radar scope and later remembered seeing the sky “filled with airplane.”

The Collision

Stewart reflexively rolled his fighter 30 degrees right to avoid a collision as Ivory II’s starboard wing guillotined off 8 feet of his port wing and external fuel tank. His fuselage impacted the rear of the B-47’s No. 6 J47 engine mount and tore off the bomber’s external tank. The Sabre Dog’s starboard wing then quickly tore away. Tumbling in a fireball, Stewart ejected and survived a 22-minute, frostbitten parachute ride from 35,000 feet into a swamp near Estill, South Carolina.

In a strange twist of aerodynamics, the wingless fuselage glided onto a field mostly in one piece near Sylvania, Georgia, about 14 miles west of the South Carolina border. Five weeks after the collision, search crews found Stewart’s radar recorder, which was attached to his canopy. Analysis clearly indicated that the fighter’s radar had incorrectly locked onto Ivory I, instead of the closer Ivory II, another one in a long line of software failures of this technology. Stewart was vindicated.

Once Richardson gained positive control of his damaged bomber at 20,000 feet, he raised the landing gear and flaps. Lagerstrom contacted Hunter AFB about 50 miles to the south and requested permission to land there. The base’s control tower informed him that renovation work on the main runway was incomplete, leaving an 18-inch vertical lip of concrete exposed at its eastern end, where Ivory II would be landing. Richardson knew that if he landed short and snagged the drooping engine or landing gear on that lip, the force of the deceleration could cause the bomb shackle to fail, and the 4-ton payload would tear forward through the aircraft, possibly detonating the impact-sensitive high explosives.

Richardson later explained: “If we hit it, that doggoned weapon would be just like a bullet going through a rifle barrel.”

And at the end of that barrel was his cockpit.

Lagerstrom also requested the tower to contact SAC Headquarters and Homestead AFB, notifying them of their emergency and requesting permission to release their “hot cargo” before landing. Richardson, however, could not wait. SAC tactical doctrine prioritized the safety of the crew in the event of an emergency. Richardson thus had the intrinsic authority to dispose of the weapon offshore, and he took matters into his own hands after a short discussion with the crew.

“So I decided then we better release this weapon,” he recounted.

DROPPING THE BOMB

As he headed south, just east of Savannah, Gerogia, a little past 1 a.m., Richardson reduced his altitude to about 7,200 feet, slowed to 230 mph and prepared to turn east into the downwind leg prior to landing. Turning east somewhere over Wassaw Sound, at the mouth of the Wilmington and Bull rivers, he instructed Woolard to release the bomb and record the coordinates.

Woolard leaned to his bombardier instrument panel on his right, flipped a toggle switch to hydraulically open the bomb bay doors, rotated back the red cover over the bomb release toggle switch and flipped it. A later comparison between the drop locations recorded by Richardson and Woolard showed little match.

Art Arseneault, a former lieutenant commander of one of the Navy’s explosive ordnance disposal units, was involved in the attempt to recover the weapon.

“Unfortunately, the No. 6 engine had been damaged, and that’s what 50% of the power to the radar was generated by,” he later said in the “America’s Lost H-Bomb” video “So we ended up with a very distorted radar picture.”

The bomb arced downward for 20 to 25 seconds. The crew searched the dark sea, but saw no detonation or splash. As Richardson continued through the landing pattern from base to final, the tower informed him that SAC had given permission to drop the weapon, but only 20 miles out over the Atlantic Ocean. Richardson informed the tower that they were too late.

CLOSE TO DEATH

Refocused on landing, Richardson dropped his speed on final to 225 mph, about 48 mph above stalling speed. As he fought to keep the right wing up, the bomber impacted the runway and bounced. Lagerstrom immediately deployed the braking parachute, and Ivory II settled onto the runway for the last time. By about 1:30 a.m., the emergency was finally over.

Richardson later said that, upon exiting through the lower hatch, “I think all three of us kissed the tarmac.”

Only then could they fully see the extent of the damage. A 9-square-foot wing section at the right aileron was crushed inward to the aft main wing spar, leaving it cracked. Debris from Stewart’s fuselage and wing had ripped holes in the vertical and horizontal stabilizers of the bomber’s tail, and had penetrated the auxiliary fuel tank in the main fuselage. Inspectors later found a chunk of the F-86’s port wing leading edge embedded in the B-47’s vertical stabilizer, jammed against the rudder post. Some aircraft mechanics were surprised that the bomber had not disintegrated in flight. Although Air Material Command deemed the aircraft repairable, the Air Force totaled it.

NUCLEAR AFTERMATH

Responding personally to this broken arrow incident, SAC commander Gen. Thomas Power and his staff hastily arrived at Hunter AFB that morning. After Richardson and his crew had slept a few hours, they completed their debriefing with Power and then rode back to Florida in Power’s KC-135 Stratotanker. During the return flight, the general approached Richardson and his crew and unexpectedly pinned a Distinguished Flying Cross on Richardson and commendation medals on Lagerstrom and Woolard for their skilled and heroic acts.

The loss of the Mk. 15 spurred an immediate and intensive nine-week search. Expecting the bomb to be buried nose-down beneath 5 to 15 feet of silt at a depth of less than 40 feet in estuarine water, the Air Force’s 2700th Explosive Ordnance Disposal Squadron and approximately 100 Navy personnel deployed sonar, galvanic (magnetic) and cable drag equipment in the search area.

“The general showed me a map of the East Coast of the United States. Right off Savannah he showed me a pencil mark and said that the bomb is right there,” Arseneault said years later. “The only problem with that was the pencil mark was a half mile wide and four miles long.”

Abandoning the search on April 16, the Air Force declared the bomb irretrievably lost.

IS the Bomb off Savannah Safe?

In the 60-plus intervening years, the lost Mk. 15 has generated a cloud of controversy. Following pressure from his constituents and the media, in early August 2000, U.S. Rep. Jack Kingston of Georgia requested the Air Force to reinvestigate the lost bomb. After consultations with the Navy, the Department of Energy, the Savannah District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, the Air Force continued to hold firm that it was in the best interest of the public and the environment to leave the bomb in place and to perform no additional searches.

Further controversy has surrounded whether the weapon contained a nuclear pit. Policy and procedures in 1958 prevented Air Force personnel from loading armed nuclear weapons onto training flights. If depot personnel did not accurately identify a pit-equipped weapon, however, then one with a pit could accidentally be loaded.

In his book “15 Minutes,” L. Douglas Keeney described the skill set of some depot squadrons: “One group was monitored as they loaded and unloaded no fewer than six different bombs on a B-47. They flunked because of errors in assembly.”

Such observations raised doubts regarding the presence of a pit in Ivory II’s bomb.

The Air Force could settle the matter by providing evidence that the capsule was stored and properly inventoried at the munitions depot. To date, however, it has yet to correct the record regarding the type of pit in question, continuing to state inaccurately there was no “plutonium” pit in the weapon. Further muddying the historical assessment, in April 1966 W.J. Howard, assistant to the secretary of defense for atomic energy, wrote a letter to the Congressional Joint Committee for Atomic Energy claiming that the Mk. 15 bomb lost near Savannah was a complete weapon — that is, it contained a nuclear capsule. The Air Force later provided data to Howard that challenged the facts of his letter, and he retracted his earlier conclusion.

One fact is clear. The extreme deceleration of the bomb as it impacted the water at a little less than 500 mph and then plowed into the silty bottom must have caused massive internal damage. The thinner nose would have crushed inward, potentially coinciding with the thermonuclear secondary driving forward through it and separating from the cast-iron outer casing, rendering the weapon no longer fusion capable. This effect had been observed in another 1950s broken arrow incident. Over time, the batteries would have disintegrated in the seawater and lost any charge needed by the electrical detonators. The shape of the high explosives would likely have been distorted, preventing the precisely symmetrical implosion required for any nuclear yield. Decades of seawater exposure would have seriously corroded the casing and exposed the explosives to further chemical alteration. In the unlikely event that the explosives detonated, the bomb would certainly be a dud. Even then, though, fragments of uranium metal could be dispersed throughout the local seabed.

Richardson’s decision to ditch his hydrogen bomb over the waters 12 miles from midtown Savannah has understandably generated a range of emotional responses from the local citizenry. Until it can either be located or retrieved, the presence of this nuclear device in Georgia’s coastal waterway will continue to produce an unending litany of doubts, fears and conspiracy theories regarding the dangers it harbors.

Timothy Karpin and James Maroncelli are the authors of The Traveler’s Guide to Nuclear Weapons: A Journey Through America’s Cold War Battlefields, available at atomictraveler.com. Additional reading: A Technical History of America’s Nuclear Weapons: Their Design, Operation, Delivery and Deployment, by Dr. Peter A. Goetz; 15 Minutes: General Curtis LeMay and the Countdown to Nuclear Annihilation, by L. Douglas Keeney; and Boeing B-47 Stratojet: Strategic Air Command’s Transitional Bomber, by Robert Hopkins III and Mike Habermehl.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.