The Americans won because the King’s best strategist guessed wrong about where Washington and his allies would fight

“I think in all probability Lord Cornwallis must fall into our hands,” General George Washington ecstatically predicted as he gazed toward the besieged British army in Yorktown, Virginia, early in October 1781. Months earlier, Washington, with the “utmost anxiety,” had been saying that he had nearly lost hope of winning the war. He was not alone. At nearly the same moment, British Army commander Sir Henry Clinton observed that the American rebellion, dogged by a ruined economy and sinking morale, was “at its last gasp.” The “King’s affairs,” Clinton added, were “going in the happiest train.” Yet by autumn of that same year, circumstance had trapped more than 9,000 British soldiers and sailors at Yorktown, threatening Britain with a catastrophic defeat.

That turn of events had not been inevitable. The reversal arose from decisions made by both sides during the preceding year. Ordered by London to retake South Carolina and Georgia, Clinton, in June 1780, followed the capture of Charleston by putting Charles, Earl Cornwallis, at 42 a veteran officer, in charge of pacifying the two southern provinces. Cornwallis rapidly ran into dogged resistance by bands of guerrillas. Concluding that success lay in denying local insurgents access to provisions streaming from the Northern states, Cornwallis twice led his army into North Carolina. Both attempts at interdiction ended in disastrous failure. Between October and March, the British lost some 2,500 men in bloody clashes at King’s Mountain, Cowpens, and Guilford Courthouse.

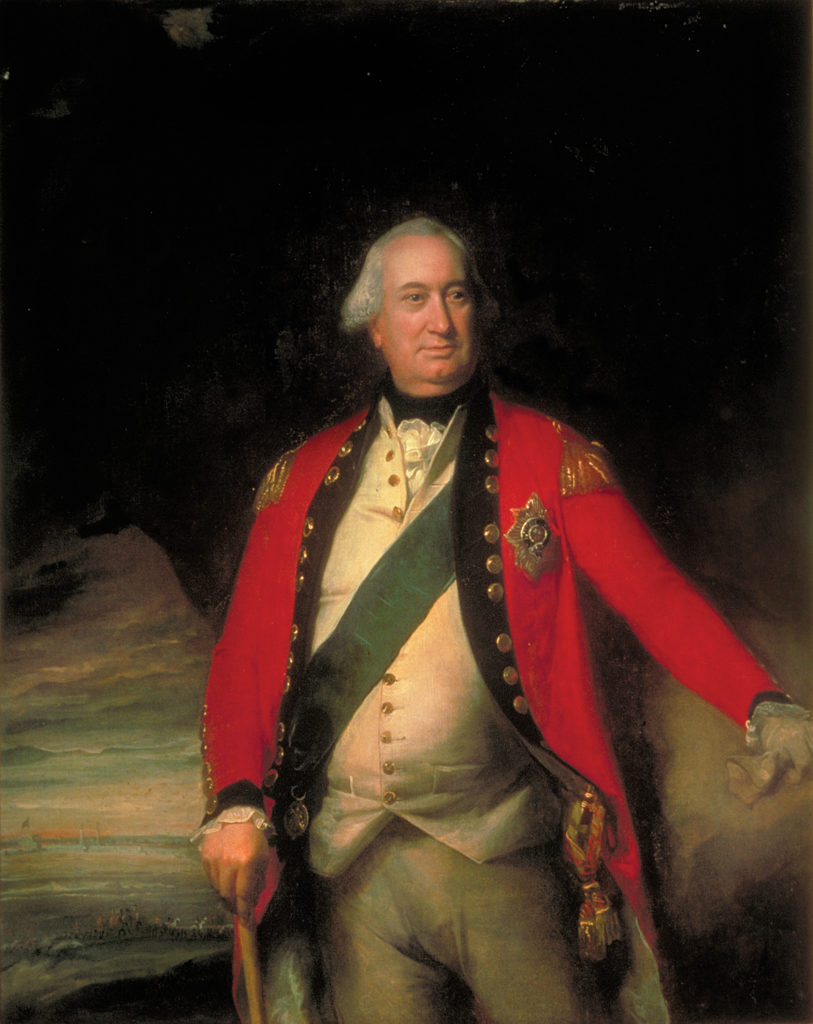

Clinton, widely regarded as the best strategist among Britain’s generals, responded to the southern morass with a new plan. Late in 1780, he committed an army of 1,800 under Benedict Arnold to Virginia to stanch the flow of supplies and establish a British base on Chesapeake Bay. Washington countered by dispatching the Marquis de Lafayette, 23, to the Old Dominion with a roughly comparable force. Clinton parried, rushing in reinforcements under General William Phillips, whose arrival brought to nearly 6,000 the number of British troops in Virginia. Besides severing enemy supply lines, Clinton reasoned, Phillips’s presence would compel Virginia to keep its military forces at home. Both factors, he thought, would enable Cornwallis to crush the Low Country rebellion.

Shortly after Phillips took command in Virginia, Washington, intent on planning strategy for 1781, met in Wethersfield, Connecticut, with Jean-Baptists Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, commander of the French army in America. Upon allying with the Continentals in 1778 France had sent only a navy to America. But the war stalemated and in 1780, hoping to break the deadlock, the French dispatched Rochambeau and 4,000 troops, with reinforcements due later. Rochambeau opened the Wethersfield conclave by disclosing that France would be providing money to its cash-strapped ally and, under Admiral Comte François Joseph Paul de Grasse, sending an additional naval force whose ranks would include 3,200 marines. Combined with the eight heavy French warships already at Newport, Rhode Island, this expansion might assure French naval superiority in American waters.

Rochambeau next asked Washington’s thoughts on the coming campaign. When Washington urged an offensive to retake New York, the Frenchman was neither surprised nor happy. Rochambeau, a professional soldier and veteran of 36 years’ service, doubted New York could be recovered. Occupying the city since 1776, the British had had ample time to fashion formidable defenses against attack and to stockpile supplies against attempts at siege. A siege would require many months. The American militiamen who would comprise half of Washington’s force served for only brief periods. Rochambeau argued that Phillips’s army in Virginia made a more tempting target. But Washington was adamant and Rochambeau reluctantly assented, later remarking that the American commander “did not conceive the affairs of the South to be of such urgency.”

The moment Washington departed, Rochambeau secretly notified de Grasse that as the Southern states were facing “a very grave crisis,” the admiral could “render the greater service” by sailing for the Chesapeake after showing the flag at several French Caribbean colonies. France’s minister to the United States also beseeched de Grasse to “do all you can” to save Virginia. Three weeks after their meeting at Wethersfield, the Allied leaders learned that Cornwallis had marched his 1,435 men to Virginia. The move violated Clinton’s orders to focus on South Carolina. Cornwallis justified his obstinacy by insisting that the only way to suppress the Southern rebellion was to conquer Virginia. The revelation of his march prompted Rochambeau to inform Washington of his request that de Grasse sail for the Chesapeake.

Early that July, Rochambeau’s army joined the Continental troops under Washington north of Manhattan. Not knowing de Grasse’s specific destination, the Allies could only wait to learn whether they would be campaigning in New York or in Virginia. Washington continued to favor attacking occupied Manhattan. Lafayette, in Virginia, had other ideas. On July 31 the younger man wrote Washington, “Should a french fleet Now come in . . . the British army would, I think, Be ours.”

As they were waiting, the French got their first good look at America’s soldiers, noting the rebel troops’ destitute condition; many were barefoot and “covered with rags.” Given appearances, it amazed the French to see that their counterparts “can march so well.” Some thought the African American soldiers comprising about 5 percent of the Continental Army were the “most precise in . . . maneuvers.”

In New York, Clinton had been preparing for an attack. In the spring, he had gotten word of plans for de Grasse’s fleet to sail for the Caribbean. Like his adversaries, he was expecting de Grasse’s squadron to come to the Chesapeake or New York late that summer. Reports from Clinton’s intelligence arm, which included startlingly accurate accounts of the Allied agreement reached at Wethersfield, convinced the British commander that New York would be the enemy’s ultimate objective. Even so, three times during the summer Clinton cautioned Cornwallis that de Grasse might be coming to Virginia.

In June, Clinton ordered Cornwallis to send him 3,000 men and “a proportion of artillery”—in practical terms, a withdrawal. But in mid-July, as Cornwallis’s men were boarding transports, Clinton canceled that order. He was acting on guidance from London that King George III and Lord George Germain, secretary of state for America, disapproved of reducing Britain’s army in Virginia. Orders were orders, and Clinton ruefully directed Cornwallis to instead “maintain . . . respectable defensive” installations on the York River at Yorktown and at Gloucester.

Clinton spent the summer strengthening his own fortifications around Manhattan. Expecting his 13,000 regulars to face an Allied force of 20,000, he activated many of the 5,500 militiamen in royal units around the city. Provided the Royal Navy remained supreme, Clinton believed, he could hold New York. Over the summer he learned that de Grasse had departed France with 28 ships of the line, more than twice as many fighting vessels as the Royal Navy had in North America. However, Clinton’s sources repeatedly advised, only a portion of de Grasse’s squadron would be sailing north from the Caribbean. Some warships would be accompanying the annual convoy hauling West Indian products to France; others, needing repair, would go into dry dock. And a British squadron in the Caribbean would be trailing de Grasse northward and joining the Royal Navy fleet already off North America. All indications pointed to Britannia ruling the waves, as ever.

In July, Clinton briefly contemplated undertaking a strike against the enemy armies above Manhattan but decided it imprudent to abandon what he—and Rochambeau—regarded as sturdy battlements. He stayed put and awaited the coming attack.

The Allies, still uncertain of where they would be campaigning, also waited. July and half of August passed uneventfully. On August 14, a messenger arrived with word that de Grasse was sailing for Chesapeake Bay. In his diary, Washington scribbled, “obliged . . . to give up all idea of attacking New York.” He then wrote Lafayette: “You will detain [Cornwallis’s] troops until you hear from me again.” Within six days both armies had crossed the Hudson and were marching south.

The Raritan River in New Jersey, the crossing of which would confirm that the Allies’ destination was Virginia, was a dozen days’ march away. To gull Clinton into thinking that their objective was New York, the combined forces built field ovens, brought in boats, and erected so a realistic “dummy camp” across from Staten Island that a Continental soldier remarked, “our own army no less than the Enemy are completely deceived.”

After the fact, Clinton came in for criticism over his failure to engage the Allied armies once they crossed the Hudson. However, certain that the enemy would be attacking New York, he refused to abandon his emplacements. Allied trickery did figure in his stance, but he was swayed more by reports from Admiral Sir Samuel Hood, commander of the British fleet in the West Indies. Alerted to de Grasse’s hoisting anchor and leaving the Caribbean, Hood’s flotilla of 14 copper-bottomed ships of the line had sailed north several days later. Reaching the Chesapeake on August 25, Hood found no sign of the enemy’s presence. Three days later—and two days before the Allies crossed the Raritan—Hood docked at New York. His report convinced Clinton that de Grasse’s destination was New York. Clinton’s misjudgment arose because Hood, aboard those much faster copper-bottomed vessels, had beaten de Grasse to the Chesapeake. Like Clinton, Admiral Thomas Graves, commander of the Royal Navy in North America, was convinced that de Grasse was sailing for Rhode Island to join the French fleet in Newport before descending on New York. Graves immediately set sail with 19 ships of the line in search of the enemy task force.

But the Allied armies were indeed on their way to Virginia, and early in September they paraded through Philadelphia. The members of Congress stood outside Independence Hall waving joyously as the soldiers passed. The congressmen’s delight grew upon receipt of France’s cash largesse. That was also good news for Washington, whose restive troops had gone unpaid for months. Soon, he distributed one month’s pay in specie to his soldiers.

From Philadelphia, the armies marched toward the Chesapeake. At Wilmington, Delaware, Washington learned that de Grasse was in the Chesapeake Bay and had landed his marines. It was now a good bet that Cornwallis could neither escape by land nor engineer a rescue by sea. Rochambeau arrived soon thereafter to deliver these glad tidings, whereupon the habitually reserved American commander exuberantly hugged him. Rochambeau probably told Washington what he told a French official, “If M. de Grasse is or makes himself master of the Bay, we hope to do some good work.”

De Grasse did make himself the master of the Chesapeake. He and his 28 ships of the line arrived at the mouth of the bay the very day that the Allies crossed the Raritan. Reaching the bay six days later, Graves and his fleet found an enemy possessed of overwhelmingly superior numbers and in a virtually impenetrable defensive array. Nevertheless, Graves and de Grasse fought the Battle of the Chesapeake that day (September 5, 1781). The two-hour engagement cost both sides heavily, but at its conclusion the French fleet remained in control of the bay. Graves withdrew to New York to seek repairs to ships damaged in the battle.

The day the navies were clashing, the first Allied troops were reaching the Chesapeake as part of a march to Virginia that had been in the planning since the Wethersfield conference ended. Provisions were stockpiled along the route. Orders had gone out to assemble a vast array of boats at the the north end of the Chesapeake. However, on reaching the mouth of the Susquehanna River marchers found too few vessels to carry men and equipment. Two-thirds of the troops had to finish the journey on foot. To eat they foraged, according to a French soldier at times obtaining necessities “not with money, but with musket shots.”

Cornwallis, who learned of de Grasse’s arrival on August 31, made no attempt to escape. By September 5 he knew French marines had united with Lafayette’s army, which guarded the landbound exits from Yorktown. It was too late to attempt to bolt for safety in South Carolina, an option Cornwallis appears to have never considered seriously. Clutching at the hope of a naval rescue, Cornwallis was unsure of his ability to break through Lafayette’s entrenched army; contemplating the notion of such an attempt by the British commander the Frenchman had boasted, “every body thinks that he cannot but repent of it.” Even if Cornwallis were able to break out and make for faraway South Carolina, he would face a long and quite possibly hopeless tramp through inhospitable rebel backcountry. Thinking it safer to hunker at Yorktown, he nonetheless told Clinton that if “you cannot relieve me very soon, you must be prepared to hear the worst.”

Unable in Graves’s absence to reach Virginia by sea, Clinton could do nothing to rescue Cornwallis. Taking his army on a 300-mile trek through the American interior would have been foolhardy, leaving Clinton to hope for two weeks that Graves would defeat de Grasse. Learning in mid-September of the outcome of the Battle of the Chesapeake, Clinton immediately convened a council of war. His officers argued against dispatching a relief force until an adequate number of heavy warships were available. Having learned that Rear Admiral Robert Digby had sailed from England, the officers held out for the possibility of the Navy cobbling together a force to save Cornwallis. De Grasse was not staying forever; he had announced that he would depart October 31. Perhaps Cornwallis had stockpiled provisions sufficient to sustain his army long enough to outlast the French squadron.

By the last week in September, word had reached Clinton that the French fleet at Rhode Island had joined with de Grasse, further enhancing the enemy navy’s numerical superiority. Digby had arrived—with only three ships of the line. Nevertheless, another council of war agreed to send a relief expedition from New York consisting of 5,000 troops once shipwrights had rendered Graves’s damaged fleet shipshape. It would be an incredibly risky undertaking, but as Clinton told London it was “not a move of Choice . . . it is of necessity.” The target date for sailing was October 5.

Washington and Rochambeau arrived in Williamsburg by mid-September, but another two weeks passed before the last Allied soldiers had gotten there and the two armies had taken up positions in a long semicircle before Yorktown. On the left were 8,600 French troops; on the right, 8,280 Continentals and 5,535 American militiamen. Against the Allied force of 21,820, Cornwallis’s ensnared army consisted of 9,725 soldiers and sailors.

Washington spoke of the “brilliant prospects” of victory. Rochambeau, a veteran of 14 sieges, said Cornwallis’s surrender was “reducible to calculation.” Seemingly, only a miracle could save Cornwallis, unless he could hold out past October 31, when, de Grasse insisted, he must haul anchor. Thinking relief from New York might soon arrive, Cornwallis wished to save his men for the fight that would ensue. On September 30 he abandoned his outer lines and withdrew to his inner defenses.

Days passed. Allied soldiers wrestled heavy artillery from the James River to the front lines. Others dug parallels and constructed redoubts and breastworks for the siege. On October 9, 51 days after the armies had begun their march, the Allied artillery barrage began. As French troops shouted “Huzza for the Americans,” Washington had the honor of discharging the first round from an American siege gun, a shot that tore through a house, purportedly killing two British officers. That salvo came four days after Britain’s relief expedition was to have left New York, had ship repairs not forced repeated postponements. The fleet finally sailed on October 19.

The American bombardment grew in intensity as the number of guns hammering the British grew to 90—at peak, gunners were firing some 3,600 rounds daily—and the Allies opened a second parallel only 300 yards from the village. Life under siege shrank to a mole-like existence. Cornwallis lived in an underground bunker and conducted staff meetings in a cave near the river. “We continue to lose men very fast,” he advised Clinton, as his soldiers were being blasted to bits and crushed by collapsing buildings. Men endured horrific shrapnel wounds and concussions.

The second Allied parallel fell short of the York River. Two British redoubts guarded that stretch. If the Allies did not take those bastions, their commanders feared, Cornwallis might hold out for as long as ten more days. Capturing the redoubts would advance the American siege line to within a stone’s throw of Yorktown, hastening Cornwallis’s surrender.

The assault on the redoubts was set for October 14, with the French attacking one, the Americans the other. Lafayette commanded the American assault. To lead that charge he selected a grizzled French officer, a decision that Colonel Alexander Hamilton appealed to Washington. Hamilton argued that to keep Americans from perceiving Yorktown as a French operation—likely, given the paramount roles played by Rochambeau and de Grasse—an American ought to command this action. Washington concurred and put Hamilton in charge. The attacks resulted in bloody hand-to-hand combat, and both succeeded, with Hamilton losing 44 men.

The siege was nearly over and Cornwallis knew it. He attempted an escape, which the French wrote off as baroud d’honneur, a doomed commander’s face-saving display. The morning after, Cornwallis, having suffered more than 500 casualties in nine days of shelling and with barely half his remaining men fit for duty, opened surrender negotiations. The talks stretched over two days; on October 19 an agreement was reached. “Cornwallis and his army are ours,” Hamilton wrote home, and indeed they were.

At two o’clock that afternoon, 8,091 British soldiers and sailors surrendered. Several Americans noted that many were “much in liquor.” Cornwallis, pleading illness, was a no-show. Brigadier General Charles O’Hara, who had soldiered on after suffering two serious wounds at Guilford Courthouse, stood in for him. Bands played through the ceremony and 50 years later a story gained traction that the British repertoire had included the currently popular song “The World Turned Upside Down.” Today most scholars doubt the anecdote’s validity.

Many runaway slaves had fled to the British army since the previous January and some 2,000 are believed to have been with Cornwallis in Yorktown. Many perished during the siege and others, at Cornwallis’s urging, bolted for freedom, hoping to avoid being returned to bondage. No one bothered to count the number of African Americans who died or were apprehended at Yorktown.

Enemy prisoners of war spent 18 months in captivity. Roughly 9 percent of the Germans and 31 percent of the British detainees died while interred. The appalling death rate among the British was greater than that of Union prisoners in the Confederacy’s infamous Andersonville prison during the Civil War. Five days after Cornwallis’s surrender, the British rescue expedition reached the Chesapeake and learned of his capitulation. Without delay, Clinton gingerly informed London of the “blow” that likely would be “exceedingly detrimental to the King’s interest in this country.” Receiving the news, Lord North, Britain’s prime minister since 1770, paced his office in an agitated state, repeatedly exclaiming, “Oh God, it is all over.” He was correct. The crushing defeat at Yorktown soon brought down North’s government, succeeded by one that pursued peace, which finally came in 1783.

The victory made Washington an American icon. Despite Rochambeau’s grasp of the dangers inherent in assailing New York and his advocacy of going after Cornwallis, generations would pass before the American public learned of the French general’s crucial role in the inception of the Yorktown campaign and of Washington’s coolness toward the endeavor.

In 1780, following the fall of Charleston, many thought Clinton the most popular man in England. After Yorktown, many in England—and, over the years, not a few historians—held him accountable for the catastrophe. Clinton emerged as a historical scapegoat despite having never ordered Cornwallis to come to the Old Dominion and in mid-summer having vainly taken the first step toward drastically reducing the size of the British army in Virginia, a step that might have extinguished Rochambeau’s ardor for a Virginia campaign. Clinton had no hand in the Royal Navy’s loss of supremacy. His great mistake was his unwavering assumption that the Allied blow was to fall on Manhattan—a sensible, well-reasoned surmise based on information at hand. However, Clinton got it wrong and his miscalculation changed the course of human events.

_____

John Ferling taught for forty years, mostly at the University of West Georgia. His fifteenth book, due out in May, is Winning Independence: The Decisive Years of the Revolutionary War, 1778-1781, (Bloomsbury Press, $35). He lives near Atlanta.

John Ferling taught for forty years, mostly at the University of West Georgia. His fifteenth book, due out in May, is Winning Independence: The Decisive Years of the Revolutionary War, 1778-1781, (Bloomsbury Press, $35). He lives near Atlanta.

*This is a web-exclusive story by American History. For more stories in print, subscribe to our magazine.