On February 6, 1922, my brother Charles Madison Lee was the first of four children born to Ellis and Nina Jensen Lee of Richland Center, Wisconsin. I was the last, born in 1937. When Charles graduated from high school in May 1939, Dad had a heart-to-heart talk with him about the world and the threat of war. He asked Charles what he would want to do if he was in the military. “Fly, Dad,” Charles responded.

Dad counseled him to do what he could to prepare for being drafted. If he wanted to fly, then he would have to attend college for two years and hope to get accepted into the Aviation Cadet program. In September 1939 Charles entered the University of Wisconsin, where his curriculum included subjects required before taking the test to become an aviation cadet. In May 1942, having passed the cadet test, Charles was accepted into the Air Force Enlisted Reserve Corps as a private. He was told to go home and await orders.

Five months later, on October 20, 1942, Charles received his orders for active duty, beginning a series of travels to several different training camps before earning his wings. After undergoing 36 weeks of intensive training, including 229 hours and 35 minutes total flying time, Charles graduated from the Army Air Forces Southeast Training Center on October 1, 1943, and received “the treasured silver wings of the Army Air Forces pilot.” Commissioned a second lieutenant, he was given leave to visit home for a short time that October.

On his way home, during a short layover in Chicago, Charles bought a teddy bear at the Union Station gift shop that he presented to me on his arrival. It became very special to me.

All too soon it was time for Charles to return to his duties. He journeyed to Tallahassee, Fla., where he trained on the new North American P-51 Mustang, and in early January 1944 to Fort Hamilton, N.Y., prior to deployment.

On December 31, 1943, Charles wrote home: “Now I will tell you some things that you must not repeat: I think I’m going to England, and will get P-51’s in combat. I won’t tell you why I think so, but accept it as a guess, and do not in any way give out any information. It is important, for we pilots are fairly valuable now, and information is very much sought after by the enemy.”

In January 1944 Charles departed aboard the ocean liner Île de France to his official posting, the USAAF base at Steeple Morden, in Cambridgeshire, England. But first the fighter pilots were sent to the 496th Fighter Training Group at Goxhill so that they could become acclimated to flying in England’s weather. There were 69 pilots from Tallahassee who made the journey up to that point as one unit, but from there they were sent in smaller groups to different fighter squadrons all over England. Ten of the pilots, including Charles, joined the 355th Fighter Group’s 357th Squadron, under the command of Colonel William “Wild Bill” Cummings. In a letter after the war, Charles’ squadron mate Ralph Schutt noted, “I am sorry to relate that only four of us finished our combat tours.”

The stability of finally being in a group, having his own plane and “getting on with it” gave Charles a sense of satisfaction. His training was paying off. On March 10 he wrote from Steeple Morden: “Yes, I’m finally in a group now—all I’ve to do is sit around and wait for my chance at a mission. That takes a while, I guess.” The letters that followed (excerpted here) described his combat service:

March 27, 1944

Today I went on my first mission. It was a pretty long one—just about five and a half hours. So, as you can well imagine, I have a darned sore hinder. Just try sitting for that long in one spot, strapped down, and see what I mean. When I came back I made one of the best landings I’ve made yet—really three points and smooth! And, besides—I got to fire my guns! We went down and strafed a Nazi airdrome. I got a “damaged” on a Ju 88 that was on the ground, and I shot the hell out of the control tower. Wasn’t over 20 feet off the ground for most of the time there on the deck. We made a second pass and my flight leader got hit. I had tracers going just in front of my plane, but they missed me. He, my leader, crash landed later. The worst part is coming home—seems that you’ll never see this island—and the hinder gets worse all the time.

March 29

Well, I’ve been on my second mission, this time into dear old Nazi-land itself. We got in close to the target, and ran into a whole flock of FW 190’s. So I stuck on my leader’s wing for quite a while, and then an FW 190 came right up in front of me. So I shot at him. I didn’t have any gunsight—the damn thing had gone out on me—but I shot anyway. I got hits on him from one wingtip to the other. Then he skidded up and looked at me. So I shot again! This time I got hits from his left wingtip to his fuselage. He started smoking and spiraled through the clouds. I claimed a probable on him. I know I damaged him, but don’t know for sure if I got him, so that’s what it has to be—probable. But then I messed up—lost my leader—so I climbed up to 28,000 feet and batted for home.

April 8

Flew two missions this week—am resting now from one. Didn’t see anything. I sweated out my engine, though—it cut out over the target. I lost 8,000 feet before it started. The other day, we went pretty far in. I saw Munich. Went down on a field, but only damaged an ME 110. Had to concentrate mostly on a damned gun that was shooting at me. They made me mad as hell, but I know for sure I got two of the gunmen—sprayed the hell out of them. Those guns, when pointed at you, blink like a light going off and on—kinda scary.

April 28

Yesterday marked the end of one month of combat flying for me. In that month I flew 57 combat hours, and in the last two missions, I flew element leader. That’s what I’ll be from now on. It means that I have another man flying on my wing and that I’m in charge of both of us.

May 15

Today, I was promoted to First Lieutenant and now wear a silver bar. That also means a raise in pay so I can increase my allotment. Also, my confirmations on the two damaged I claimed came through. So, all claims are now confirmed: one probable and five damaged, and one gun emplacement shot up. I have 84 combat hours now, but the length of the tour has been put to 300 hours instead of the 200 hours it was before. That puts further in the distance the time I’ll get home, but will probably shorten this war. That 84 hours is almost 20 missions. I flew six out of seven days last week, all climaxed by the longest raid for the fighters in this war.

May 20

Dad, there’s one thing for sure I know I can do—that’s fly in fog. Recently I hit some bad stuff on the coast. Flew at 10 to 20 feet all the way home. Visibility was 500 yards that day, and I got three other men home okay. This low stuff is really fun. The sensation of speed and all that—but it gives gray hair, too.

May 25

Very recently I flew three missions inside 30 hours—one in the morning, one late in the afternoon, another the next morning. A total of 13 combat hours inside the 30. One was to Berlin, the others in France—saw the Alps in the last one. The thing that makes me feel good about it all, though, is that on the last one, I flew as flight leader—had three other ships on me. My regular flight leader is grounded, so that makes me deputy flight leader now. I’ve rounded out 108 hours in two days less than two months. At this rate, I should get home next fall, just like last year.

June 7

Just a short line to tell you that I’m okay and did not fly at all yesterday—instead I was in the hospital. I get these terrific headaches from too much flying—flew five in a row and then got one. I still have part of it, but am staying in the barracks for a while.

June 20

The war seems to be going okay—as you can see in the news, we do have air supremacy—and probably another two years will see this thing finished over here. There is a tremendous job ahead of us, and it will be no “this summer” affair as far as I can see. I’ve thought about myself these last few days and realize I have one hell of a way to go to be a man. Hope some day I can say that—and at the same time, a human being.

June 25

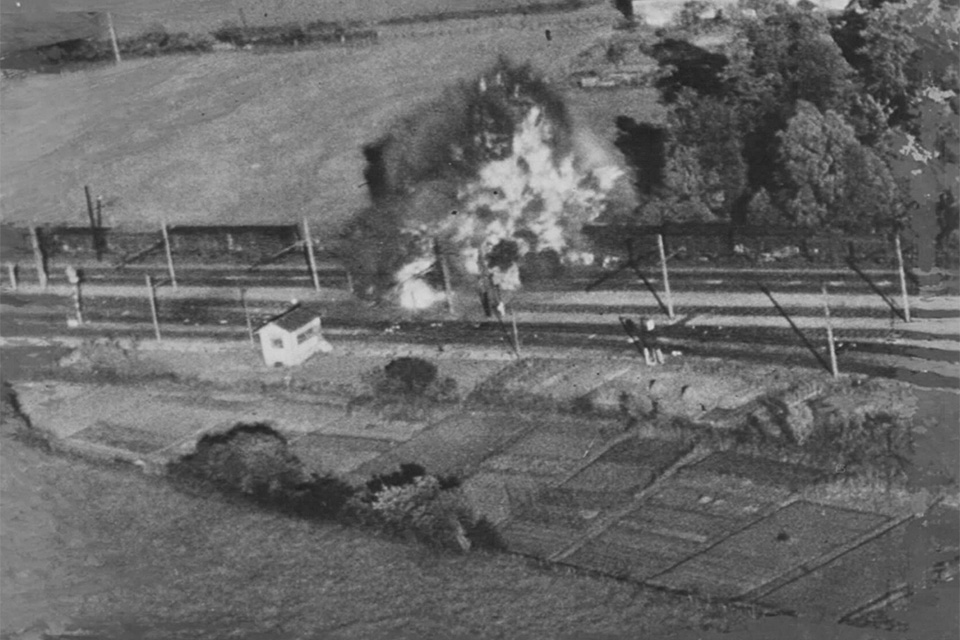

I flew a six-hour job today and led the squadron all the way. That is a much harder way to fly—there is no one to “fly on,” and at high altitudes over here, there isn’t much horizon. A lot of halfway instrument flying must take place. I’m at 178 hours now. The other day, I led a flight on a glide bomb job. I got an ammunition train in a marshalling yard. I put five of six right in the yard. The resulting explosions flamed at least 1,000 feet high. In the melee, I added two more nicks: one on a prop blade, one on the right wing. That’s the seventh in my plane now. The damn thing is getting quite patched.

July 10

My time is up to 197 hours now—just three short of two-thirds of a tour. As yet, I’ve destroyed none, but have recently shot up two more locomotives, and a couple of Huns with rifles who were pot-shooting at us when I took my flight after the locomotives.

August 6

This last week, I’ve been flying quite regularly, and have only 59 more hours to go. I am in need of a rest—it is getting so that one mission makes me so damned tired that I must have 12 hours’ sleep before doing anything. I ought to go to the Flak home [rest and recuperation centers operated by the American Red Cross], but doubt if I will. My tour should come to an end by the first week next month, then I shall be given some instructor’s job—or some similar drudgery for three months—then perhaps home for a 30-day furlough.

There were times, here and there, when Charles flew two sorties in one day, notably three days before D-Day and again on June 8. He had completed 58 operational sorties with a total time of 248 hours and 55 minutes before a mission to Saint-Dizier, France, on August 8.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Ten days later my parents received a dreaded telegram from the adjutant general stating, “The secretary of war desires me to express his deep regret that your son First Lieutenant Charles M. Lee has been reported missing in action….” The telegram was the beginning of an ongoing exchange of letters between Dad and various individuals at the War Department expressing his growing sense of grief and frustration at the lack of information about Charles’ fate. He naturally wanted to know what caused him to be missing in action—how it happened, where it happened and where was his son?

The responses Dad received over the next year seemed to be along the same lines: “We are working to learn the details; we continue to seek information from those in Europe,” etc. Dad was convinced that Charles’ fatigue was the primary cause of him being MIA. He blamed the doctors for clearing him to fly in spite of his fatigue, and he blamed General Henry “Hap” Arnold for upping the number of required hours from 200 to 300.

One letter to Dad, written by Brig. Gen. Leon W. Johnson on July 23, 1945, succinctly stated the War Department’s perspective. Although it was probably very hard for Dad to digest, I believe it may have helped him see the other side of the argument. Johnson wrote:

“…As far as locating your son or at least his grave, I can only give you the assurances which others have given, that is, that search parties have been doing and are doing everything they can to clear up these matters.

“…[T]he youngsters were willing to do anything ever asked of them. They were magnificent; their commanders wanted to save them, but if they acted too conservatively, they would prolong the war and thousands of other Americans would be killed.

“…There is no question of being tired; everyone was tired after a period of prolonged operations. Certain situations developed where the continuous operation did well to shorten the war and everything moved at top tempo. You have only to look at the photos of the ground soldiers in action to see utter fatigue; the same applied to all services. But, this extra effort and drive was the thing which defeated the mighty German nation; it was the thing which saved thousands of other Americans the grief you are undergoing.

“…Our boys knew the score; they were tired, yes; scared, yes at times; but perfectly magnificent; willingly going forth to fight for that in which they believed. I am proud to belong to a country which can produce boys such as your son.”

A year and one day after Charles went missing—the same day America dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, effectively ending World War II—Maj. Gen. Edward F. Witsell wrote to my parents: “In view of the fact that twelve months have now expired without the receipt of evidence to support a continued presumption of survival, the War Department must terminate such absence by a presumptive finding of death.” On December 18, 1945, Witsell wrote with some information about Charles’ last mission, saying that “Your son’s aircraft was seen at 2:25 p.m. to crash at St. Dizier, France, and was lost as a result of antiaircraft fire.” The letter included details from one of Charles’ wingmen, 1st Lt. Edward P. Ludeke, who said that Charles’ P-51B had been struck by fire during a strafing run, began trailing smoke and flames, turned on its back and crashed.

In March 1946 Dad and Mom received a letter advising that Charles had been posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart and more Oak Leaf Clusters to his Air Medal. Another year passed before they received a letter from Brig. Gen. G.A. Horkan with a picture of the U.S. Military Cemetery Champigneul in Marne, France, where Charles was buried.

In January 1948, another wingman, Charles Salinski, initiated contact with Dad and provided a full description of the event: “The day Charles went down, I was on my last mission and he was about two or three missions from completing his tour of duty. We were strafing an anti-aircraft tower and he was just ahead of me. He finished firing and pulled up, then I started to fire. Out of the corner of my eye I saw his plane pull up steeply and falter. They had evidently hit him as he passed over them. He was only about 3,000 feet up when he started to dive, so it was over in a split second. It should be a consolation to you to know that it happened quickly and was over before he had a chance to realize it.”

Salinski and Dad exchanged several letters, and I know Dad was extremely grateful for his frank and complete answers.

In May 1946 Public Law 383 had authorized the Army to spend $200 million to repatriate GIs, sailors, Marines and civilian federal employees who had died abroad between September 1939 and June 1946. In July 1947 my parents received a form letter elaborating on the Public Law along with pamphlets that would help them decide if they wished to have Charles brought home.

More than a year after Dad and Mom filed a Request for Disposition of Remains Form, they received an acknowledgment that provided information from the official report of burial: “The remains of your son were originally interred on 9 August 1944 in the Communal Cemetery of Etrepy, Marne, France. This report of burial further discloses that his remains were buried by the Mayor of Etrepy, France, and the grave was marked with a large wooden cross with the inscription ‘aviateur allie charles m. lee, 1944.’”

By 1949 all the worry and stress was easing. My parents received a lengthy telegram on March 9, advising that Charles’ remains were en route to the United States, and confirmed the delivery destination was Richland Center. Dad and Mom began to make preparations for his final interment.

Charles finally came home on April 27. I still recall that day, when Dad said to me, “Nina Kay, do you want to go to the train station with me? Charles is coming home today.” Of course I said yes. We drove to our small town’s train station and watched as two men maneuvered the shipping container from the boxcar into the back of the funeral home truck. The funeral home folks brought the casket up to the house for a day before the burial service. Dad sat for hours on the bench in our front hall that next day, his hand resting on the beautiful bronze casket that held Charles’ remains, as he remembered and mourned. His boy was finally home…home for all time.

As long as I am alive, my memories of Charles will be alive as well—as treasured as that now-raggedy, much-loved teddy bear.

Nina Lee Soltwedel performed extensive research to compile two booklets about her brother Charles, from which this article is adapted. In 2008 her son Eric visited Steeple Morden and in 2013 took a flight in a P-51D while carrying a photo of Charles. Further reading: Angels, Bulldogs & Dragons: The 355th Fighter Group in World War II and Our Might Always: The 355th Fighter Group in World War II, both by James William “Bill” Marshall; and Steeple Morden Strafers 1943-45, by Ken Wells.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2022 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe today!