When Private First Class Francis S. “Frank” Currey arrived in Malmedy six days before Christmas 1944, the Belgian town wasn’t yet notorious for a massacre. Eighty-four dead AmericanPOWs still lay out beyond the lines at a crossroads south of town, where Nazi Waffen-SS troops had gunned them down two days earlier, but the full horror wouldn’t be known for weeks. The immediate worry for American troops then in Malmedy was focused on a bridge. The great German thrust through the Ardennes west toward the Meuse River in Belgium and France—an offensive best known as the Battle of the Bulge—had stalled. But if the enemy took the bridge over the Warche River, west of town, the Nazi offensive would roll again.

Currey’s unit, Company K, 120th Regiment, 30th Infantry Division, had been hurriedly trucked down from Holland to bolster the front after the Germans launched the offensive on December 16. “They spread us out pretty thin,” Currey, 19 at the time, recalled in an interview seven decades later. Stories of German infiltrators dressed as Americans and imitating Allied MPs, changing street signs, mining roads, and cutting phone wires behind American lines, along with collaborators in Malmedy—for much of its existence part of Germany—had the troops on edge. Indeed, although the Americans didn’t know it, two teams of disguised Germans had passed through Malmedy just before the arrival of Currey’s unit on December 19, found it lightly defended, and reported back to their commander a few miles to the south.

That man, SS Lieutenant Colonel Otto Skorzeny, was an ardent Nazi with no compunctions about fighting dirty. A six-foot-four Viennese with a face marked by schmisse—dueling scars—he would write in his memoirs, “My knowledge of pain, learned with the saber, taught me not to be afraid. And just as in dueling when you must concentrate on your enemy’s cheek, so, too, in war. You cannot waste time on feinting and sidestepping. You must decide on your target and go in.”

In September 1943, Skorzeny had led a glider-borne attack on a mountaintop prison at Gran Sasso, Italy, and snatched former dictator Benito Mussolini back from the turncoat Italians. In October 1944, he had taken the son of Hungarian regent Admiral Miklós Horthy hostage to keep the country fighting for Germany. Such exploits had made Skor-zeny infamous among the Allies as Hitler’s favorite commando; they called him “the most dangerous man in Europe.”

For the Ardennes offensive, Hitler had personally ordered Skorzeny to assemble Panzerbrigade 150—a unit of ersatz Americans, with tanks and assault guns modified with steel cladding, olive drab paint, and white stars—to masquerade as Allied armor and capture strategic river crossings for the German Sixth Panzer Army. Skorzeny’s force also included the smaller infiltrator teams disguised as U.S. troops, whose actions behind Allied lines were making the real Americans nervous. Learning of the deception, the Allies feared the German objective was to kidnap or kill commanding general Dwight D. Eisenhower—a rumor the Germans had created and encouraged.

While Skorzeny’s handful of disguised commandos was causing chaos behind American lines, however, his armored battlegroups had not even seen action. The German spearhead had bogged down in a maze of Allied roadblocks and blown bridges to the west, and his imitation American tanks were trapped with most of the German army in a massive traffic jam behind it.

Skorzeny realized that as the Germans focused on driving to the Meuse River, they had left the north flank of the 70-mile opening they had created in the Allied lines—the “Bulge”—relatively unprotected. “The enemy could easily thrust southward through the road junction at Malmedy,” Skorzeny noted, which would give the Americans a chance to cut the German salient in half. At the same time, the opposite was also true. With the German westward advance contained, the little span over the Warche River just west of Malmedy offered the Germans a way north, out of the box. That made the bridge a vital German target. Said Skorzeny: “We decided to make a surprise attack on Malmedy, at dawn on the 21st.”

PROTECTING THAT BRIDGE had fallen to young Currey’s unit. “There was only one squad of us,” he recalled: “about eight of us.” The road from Malmedy to the bridge ran west between an abandoned paper mill and the American command post—a house full of machine-gun teams, 33 men in all. “We were all teenagers,” Currey remembered. “The oldest one was maybe 21 years old, and I was the one with all the training.”

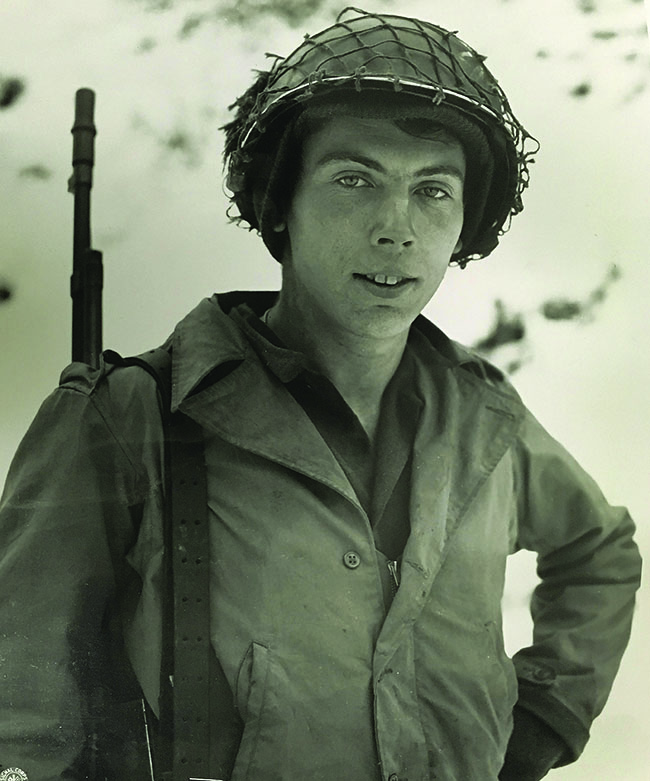

At six foot three, but only 130 pounds, Currey had joined the U.S. Army a week out of high school at age 17 and, even after completing Officer Candidate training, was still too young to fight overseas, let alone become an officer. “There are two groups of people,” was his philosophy: “those who get things done, and those who take credit for getting things done. Belong to the first group. There is much less competition.” After turning 19 in June 1944, Currey landed in France, caught up with the 30th Division in the Netherlands, and fought with the 120th’s Company K as an automatic rifleman, through Aachen, Germany, and down the Roer Valley. Said Currey: “I knew what I was doing.”

The same might not be said of Skorzeny, a special-ops leader who, despite his exploits, was in his first battlefield command. For one thing, his intelligence was outdated. Since his infiltrators had reconnoitered Malmedy, the Americans, realizing it was key to holding the north flank of the Bulge, had sent in nearly four battalions of infantry with artillery, antitank guns, and tank destroyers. Strongpoints and minefields guarded the roads leading to town.

One of Skorzeny’s tank commanders, Captain Walter Scherf, recalled, “Malmedy was supposed to be enemy-free. Based on my own knowledge of the general situation I felt that this information couldn’t be correct…. I was understandably uneasy about carrying out an operation at night against positions already occupied by American infantry and artillery, who had already been able to adjust their fire.”

Scherf was a decorated veteran commander. Through 1943-44, he had led a company in the 503rd Heavy Panzer Battalion on the Russian Front. He held both the Iron Cross and German Cross in gold, and had an army man’s disdain for the SS: “Skorzeny and I were upset with each other,” he reported. “He—a Waffen-SS man—wanted to tell an experienced army panzer man how things were done!… There were often differences of opinion about ‘troop leadership.’ I was sure that the mission would be a flop.”

Regardless, in the early morning of December 21, Skorzeny went against his personal philosophy of direct assault by launching a diversionary attack. He sent Scherf with his disguised assault guns and 120 men up the main road from Ligneuville, north toward Malmedy. In darkness and fog they felt their way through frozen woods toward a crossroad called Baugnez, southeast of Malmedy, where the massacred American POWs still lay in the snow. Just to the north of it, the lead half-track ran over a mine. By the light of the burning vehicle, some of the Germans spotted an American outpost and ran toward it, yelling, “Hey, we’re American soldiers. Don’t shoot!”

Even with their extra plating and green paint, though, the German tanks and assault guns bore only a superficial resemblance to Allied armor; Skorzeny himself had figured they would fool only “very young American troops, seeing them from very far away at night.” Even at that, he had overestimated. The Americans didn’t fall for the trick. They immediately opened fire, knocking out a tank destroyer behind the half-track.

Company B commander Captain Murray S. Pulver was in charge of the American roadblock. “Very soon we began receiving heavy mortar and machine-gun fire,” he recalled. “I radioed battalion headquarters and requested immediate artillery support. I think every gun in the 230th Field Artillery Battalion fired in our support. A colonel at division kept repeating, ‘Captain, hold at any cost.’”

As the rippling flashes of artillery blasts revealed more and more German casualties, the attack faltered. “The battle group had already lost 60-70 men, dead or wounded, by this point,” reported Scherf. “I wasn’t prepared to lose any more men and vehicles in the dark without reaching Malmedy so I ordered the battle group to drop back slowly.”

His tanks reversed and rolled back into the cover of the woods. An American squad, however, captured several survivors of the lead half-track, one of whom revealed that the attack was just a diversion from the main thrust west of Malmedy. Skorzeny had sent two companies of panzergrenadiers and paratroopers via side roads, with armored cars, jeeps, a captured M4 Sherman, and four disguised Panther tanks—their turret cupolas removed to resemble American M10 tank destroyers—to take the bridge over the Warche.

“WE HAD HEARD IN THE DISTANCE some firing,” remembered Currey, at his outpost at the bridge, two and a half miles from Baugnez. His squad had little in the way of big guns. “We had an antitank platoon,” he recalled; “they had set up way up in front of us an antitank gun and left their half-track back with us.”

To reach the bridge, Skorzeny’s two companies had to cross a bare valley floor, some 1,500 yards wide, flanked to the east by a 15-foot-high railway embankment. The diversion at Baugnez had already failed when, a little before dawn, Waffen-SS grenadiers and paratroopers in German uniform led the way. An American outpost radioed sighting a U.S. Army jeep and Sherman tank coasting down into the valley with their motors off. They were only partway across when the jeep hit a mine. Parachute flares popped overhead. The Germans were caught in the open.

American troops who had been dug in atop the embankment cut loose. Muzzle flashes flickered. Red tracers darted through the pale yellow light of the flares. American artillery unleashed an immediate barrage that would eventually total 3,000 rounds, including new top-secret proximity-fuzed airburst shells.

Amid the ear-shattering noise, peppered with shell splinters and raked by flanking fire, two Panther tanks peeled off to clear the Americans from the embankment. Panzergrenadiers and paratroopers huddled behind them against the sleet of American bullets. The lead Panther hit a mine, lost a tread, and went up in flames. Its commander, the sole survivor, bailed out and ran back to take over the second tank, whose commander had taken a fatal headshot.

The Americans kept pouring it on. “Our mortars ran out of ammo, our machine guns were low on ammo, and our hand grenades were running low also,” remembered Staff Sergeant Roland I. Asleson, of B Company, 99th Battalion, manning the embankment. He saw the surviving panzer fall back toward the ridge, leaving the Nazi infantry unsupported.

“The damned fools came across there yelling, ‘Surrender or die,’” remembered Jim Humble, an infantryman with the 99th Battalion. “You know who was going to die. They were right at the base of the embankment, at grenade-throwing distance.”

“A few Germans got to the base of the railroad embankment,” Asleson said, “but came no closer as our artillery fire, hand grenades, and rifle fire held them off. We had not given an inch, and they lost some hundreds of men.”

But the Germans knocked out the antitank gun in front of Currey’s squad. The remaining three tanks crossed the valley and reached the main road. The lead tank, another Panther, shrugged off small-arms fire from Americans in houses along the street and made for the bridge. Earlier, the 291st Combat Engineer Battalion had wired the span with explosives and explained the use of detonators to the men of the 120th Regiment, but according to an after-action report, “apparently those devices were not particularly high on [the 120th’s] list of things to remember in the event of an attack. In fact, for safety’s sake, someone had disconnected both detonators.”

The Panther came straight at Currey. “He’s coming down the road and I’m in a foxhole right beside the bridge,” Currey recalled. “The German commander is standing up in the tank…looking down at me. I had my Browning Automatic Rifle and I opened up on him.” The tanker ducked for cover down inside his turret, and the Panther rolled past Currey and across the bridge. On the far side of the Warche, the tank turned in beside a stone house full of wounded Americans so it could cover the German advance. Against all odds, the Germans were achieving their objective.

“Next thing we knew,” Currey said, “here comes another German tank, headed for us.” It was the captured Sherman. Too exposed at the bridgehead, Currey and his squad scrambled into the abandoned paper mill. “There were a bunch of windows on the first floor and we would fire from a window and then move to another window and fire…they thought there were a lot more of us,” he said. “When the tanks fired on us, we were gone. It was two stories tall, so they thought we had a pretty good-sized outfit.”

Currey and another Company K man, Private First Class Adam Lucero, found a bazooka and rockets in the building. “[The Sherman] had come right where our old position was, but he had turned around,” Currey said. The Americans put a lucky shot into its turret ring, freezing the turret. The Sherman’s crew bailed out, but the remaining Panther rolled up on the American command post across the road from the paper mill. First Lieutenant Kenneth R. Nelson of Company M led his machine-gun platoon’s defense as Germans closed to within 20 yards, but was hit. Sergeant John van der Kamp took over and was also hit, but carried on. Both won the Distinguished Service Cross, Nelson posthumously. Undeterred, panzergrenadiers reached the building and began tossing grenades into the basement windows.

At his fog-shrouded command post, on a ridge to the south, Skorzeny said, “I could only guess what was happening up front by the noise of the fighting and the vehicles returning with wounded men.” As the fog lifted he looked down to see “our tanks engaged in a hopeless struggle with a superior force of the enemy.”

“We were firefighting with German infantry,” Currey said. “There were three of them in one door [of the American command post]. They didn’t know I was there. I opened up on them with my Browning. Took care of them.” Currey’s squad then covered him as he ad-vanced with the bazooka to within 50 yards of the building, popped up from hiding, and fired a rocket that downed half a wall. As the dust cleared, he spotted the American antitank crew ahead of him, dug into foxholes near the wreck of their gun. Amid the rubble, the explosions, and the bullets zipping low overhead, Currey elbowed his way out to their position, asking, “What the hell is going on here?”

“We can’t move with them damn tanks there,” one of the tank destroyer men told him. “How the hell did you get up here?”

“Well, infantry, you know,” Currey replied. He was out of rockets and his Browning was useless against armor, but he remembered that the antitank crew still had some resources: “They had left their half-track, and there was a whole case of antitank [rifle] grenades and the launcher.” Currey darted back to the half-track, fixed a grenade to an M1 Garand and let fly at the nearest Panther. “They make a hell of a noise and a big burst of flame and smoke. It looked like an artillery shell hit it. I started bombarding them with antitank grenades.”

The Panther’s commander had been hit and staggered back to the rear on foot. Rocked by Currey’s pocket artillery, his crew abandoned their tank and took cover in the half-destroyed American command post, now cluttered with dead Americans and German paratroopers and grenadiers. Currey didn’t give them a break, but unlimbered the half-track’s .50-caliber machine gun and laid into the house. When that ran dry, he dropped back to a .30-caliber machine-gun nest near the bridge, whose crew had been killed, to protect the antitank men in their foxholes. “I got that light machine gun going, and as I started to fire to cover them, each of the men managed to get back.”

Now only the lead Panther remained across the river. Second Lieutenant Arnold L. Snyder, a forward artillery spotter, crept up behind it with a bazooka and shot it into the engine compartment. The tank began to burn. The crew tumbled out and ran for the bridge. American troops shot all but one dead as they tried to cross. Dodging bullets, the survivor ducked back into the ruined command post and climbed up into the hayloft; there he would hide for nearly a week before surrendering.

THE BATTLE WAS OVER. By the time darkness fell, both sides were running low on ammo. Other Germans sheltering in the former command post made a breakout and retreated, back across the valley.

“The enemy artillery never let up for a moment,” reported Skorzeny, rallying the survivors atop the south ridge, “and every second we expected the infantry assault which could hardly fail to succeed.” Under continued shelling the surviving Panther crashed into Skorzeny’s command post; shrapnel hit him in the face. When a German artillery battalion finally arrived, it had only 16 shells available. Skorzeny’s summary was dry and understated: “This incident was,” he wrote, “perhaps characteristic of many parts of the front during the Ardennes offensive.”

The Americans were in little better shape. Currey and four others—two wounded—took a jeep west, toward the American rear.

“It was a dark night, and we had the small [blackout] lights on the jeep,” Currey recalled. “We were going, but we did not have the slightest idea of where we were in the middle of Belgium. We hit another [U.S.] regiment, a roadblock, and we were coming from the German side. We were challenged because they were worried about Germans infiltrating, but finally they let us in and took our weapons, our jeep, and our wounded. The next day, they moved us back to our regiment.”

To forestall a repeat assault, the Americans blew the Warche bridge themselves. Tragically, Allied headquarters, believing Malmedy had fallen to the Germans, bombed it on December 23–25, causing more deaths than at the infamous massacre for which the town is remembered. After the war, Skorzeny, Scherf, and other members of Panzerbrigade 150 were tried for the Malmedy Massacre and absolved, having had nothing to do with it. “My acquittal by the Allies, against whom we had worked and fought, was a record that we had only done our duty as good Germans,” Skorzeny said.

When Frank Currey returned home in August 1945, it was as a sergeant with three Purple Hearts and a Medal of Honor for his conduct at Malmedy. “Personally I consider it a great honor,” he says, echoing the sentiments of many other Medal of Honor recipients. “We don’t wear it for ourselves, we wear it for them that were with us…. I couldn’t have done it alone.”

Now 93 and living in the Catskills of New York, Currey has been pictured on a sheet of U.S. postage stamps and modeled for the first in a series of “Medal of Honor” G.I. Joe action figures. But he has always downplayed his heroism on December 21, 1944. Decades later, Currey says simply, “As far as I was concerned, that was just one day in nine months of battle.” ✯