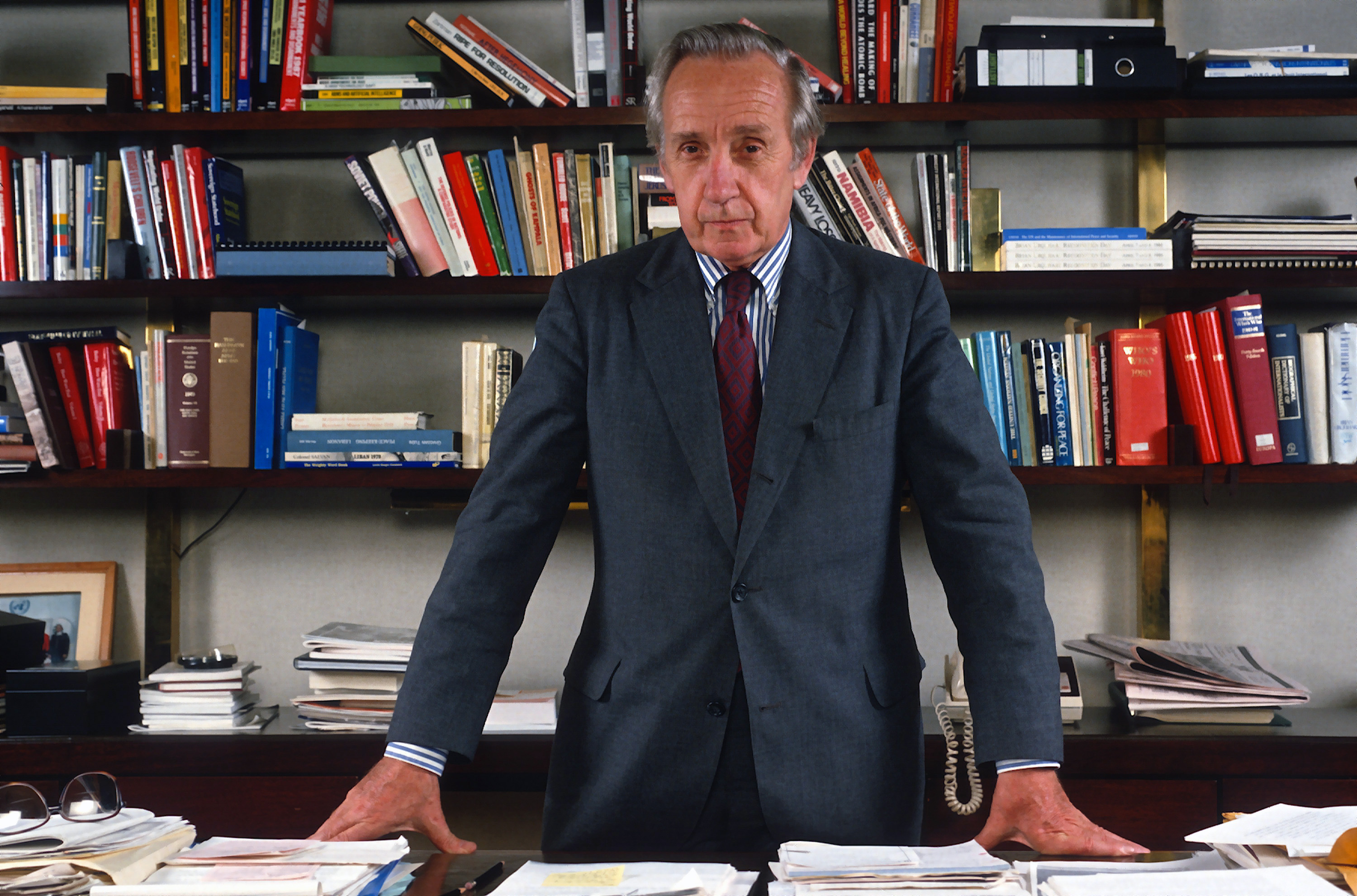

“The worst way to make an argument is by reason and good information,” Sir Brian Urquhart, the British diplomat instrumental in the earliest days of the United Nations, told the New York Times in 1982. “You must appeal to people’s emotions and to their fears of being made to look ridiculous. I also learned that if you happen, by some chance, to get something right, you become extremely unpopular.”

Such was the then-25-year old’s experience in the lead-up to Operation Market Garden — the disastrous Allied attempt to liberate the Netherlands in September 1944. As a chief intelligence officer within the British Army, Urquhart was one of the few who warned that the plan was flawed.

The calamitous operation caused more than 17,000 Allied forces to be killed or wounded, and it was this fact that continued to haunt Urquhart until his death this past Saturday at his home in Tyringham, Massachusetts. He was 101.

Planned by British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Operation Market Garden was an unprecedented airborne assault behind enemy lines. The intent was to seize several strategic bridges along the Rhine, but Urquhart openly “worried that the British command had grossly underestimated the Germans’ strength and ordered an air reconnaissance mission that revealed the presence of two Panzer divisions near the Allies’ drop-off point,” writes the Washington Post.

On September 15, 1944, two days before the attack occurred, Urquhart — who had been roundly dismissed by his British superior, Lt. Gen. Frederick A.M. “Boy” Browning — because of his adamance, was forced to take leave by Col. Austin Eagger, a medical officer who cited Urquhart as suffering from “hysteria” and “nervous exhaustion.” If Urquhart refused to take leave, he was told he would be arrested and court-martialed.

In his subsequent memoir, A Life in Peace and War, Urquhart wrote:

It was, of course, inconceivable that the opinion of one person, a young and inexperienced officer at that, could change a vast military plan approved by the President of the United States, the Prime Minister of Britain, and all the top military brass, but it seemed to me that I could have gone about it more effectively. I believed then, as most conceited young people do, that a strong rational argument will carry the day if sufficiently well supported by substantiated facts. This, of course, is nonsense….

The Arnhem tragedy had a deep and permanent effect on my attitude to life. Before it, I had been trusting and relatively optimistic, with a self-confidence that was sometimes excessive. After it, I doubted everything, tended to distrust my own as well as other people’s judgment, and became deeply skeptical about the behavior of leaders. I never again could quite be convinced that a great enterprise would go as planned or turn out well, or that wisdom and principle were a match for vanity and ambition.

The failed operation was later chronicled in Cornelius Ryan’s best-seller, A Bridge Too Far and Richard Attenborough’s subsequent 1977 film adaptation. Urquhart’s character was renamed “Major Fuller” in the Attenborough film to avoid confusion with the British general Roy Urquhart, the commander of the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem.

Discharged as a major in 1945, Urquhart was further cemented in history through his work with the then-newly formed U.N. Deeply affected by the events of Market Garden and later, as a witness to the horrors of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, Urquhart became a seminal leader for peacekeeping operations around the world.

Motivated by “idealism of a very practical kind” coupled with a keen intellect, Urquhart “worked as a principal adviser to five UN secretaries-general, directed 13 peacekeeping operations, recruited 10,000 troops from 23 countries, and instituted peacekeeping as one of the core tenets of the Organization,” writes U.N. News.

The U.N. official also possessed a wry, understated sense of humor, once quipping to reporters in 1961 — “Better beaten than eaten” — mere moments after surviving a bloody attack by Congolese secessionists in Elisabethville.

These qualities continued to serve him well throughout his extraordinary life.

Born in Bridport, England, on February 28, 1919, Urquhart was one of two sons of Murray and Bertha Urquhart, neé Rendall. Murray, dubbed by Urquhart as “the century’s least successful painter,” abandoned the family when Urquhart was just seven-years-old.

His mother, a teacher at Badminton School in Bristol, enrolled the young Urquhart there. He was the only boy among 200 girls. He later graduated from Westminster School in London in 1937 and enrolled at Oxford University before his studies were cut short at the onset of World War II.

Perhaps the U.N. official’s greatest legacy, which was not spelled out in the U.N. charter, was the practice of deploying neutral, unarmed or lightly armed soldiers to crisis zones around the world. The now familiar and distinctive powder blue helmets of U.N. troops was the brainchild of Urquhart.

Instrumental in the creation of peacekeeping forces, Urquhart once slyly remarked that the “Blue Helmets,” as the soldiers were known, were “an army without an enemy — only difficult clients.”