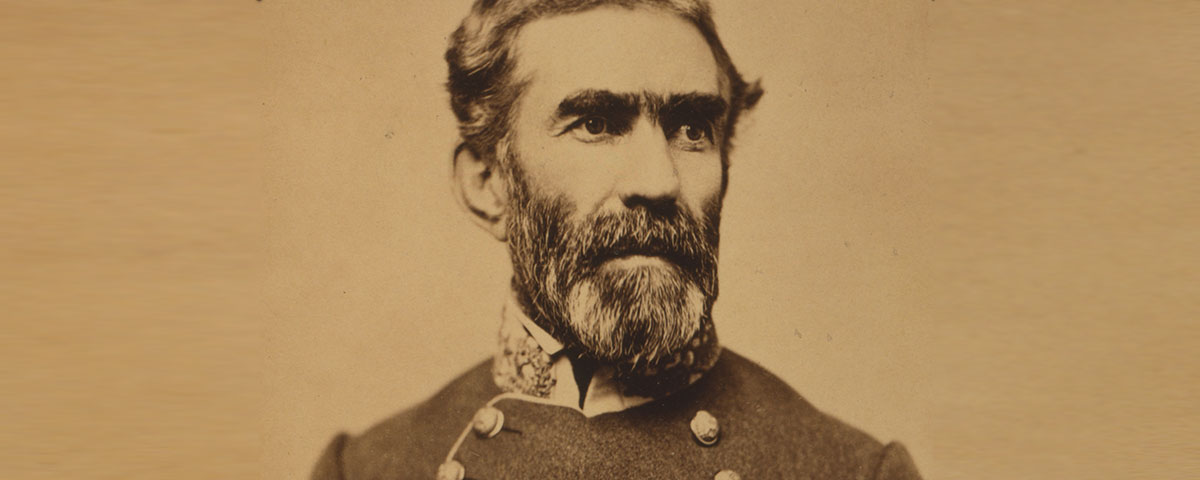

BRAXTON BRAGG IS on just about every historian’s short list of most despised confederate generals. Usually his record on the battlefield is the reason for that. As one expert wrote, Bragg was the “architect of a remarkable record of defeat.” But his overall prickly demeanor, lack of charisma and reputation as a stickler for discipline are culprits as well. About the only compliment Bragg ever received was that he was a “good organizer and administrator.” He never inspired his troops the way Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson could, and he counted more enemies than friends among his officers. In fact, Lt. Gens. Leonidas Polk and D.H. Hill, commanders in Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, were among his most vocal and vehement critics. But despite Bragg’s many well-chronicled setbacks, he rarely gets credit for conceiving and executing the only truly brilliant strategic move made by a Confederate army during the war when he decided to transfer his base of operations from Tupelo, Miss., to Chattanooga, Tenn., in the summer of 1862 and then invade Kentucky that fall. Although that latter campaign ended with the Confederates abandoning the Bluegrass State, Bragg did manage to secure Chattanooga, gain control of Cumberland Gap and frustrate Ulysses S. Grant’s powerful Union army by shifting the main front of the Western Theater from northern Mississippi to Middle Tennessee. Those achievements are indeed worth closer examination.

It would prove a mixed blessing for Bragg when he assumed temporary control of Department No. 2 on June 17, 1862, after an ailing General P.G.T. Beauregard took medical leave and relinquished command of the army. Three days later, President Jefferson Davis made the assignment permanent. Bragg, however, was in an unenviable position. At the time, Federal flotillas were teaming unmolested on the Mississippi River above and below Vicksburg. The right flank of the Union forces extended into Mississippi, the center occupied northern Alabama and the left threatened Cumberland Gap.

The situation called for a “defensive-offensive” policy: That is, Bragg would assume a defensive posture and attack only should an advantageous opportunity present itself. Union Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck had 104,000 troops around Corinth, Miss., opposing Bragg’s 42,000 at Tupelo. The 4,000-man garrison at Vicksburg anchored Bragg’s left flank, 7,000 men guarded Mobile, Ala., and 11,000 more were scattered from northwestern Mississippi to southeastern Louisiana. Bragg regarded East Tennessee as his right flank, where 11,000 troops under Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith were scattered between Chattanooga and Cumberland Gap. Eight thousand Federals in Kentucky threatened the Gap; 7,000 in northern Alabama threatened Chattanooga; and 7,000 occupied Middle Tennessee. Though Smith was outnumbered 2-to-1, the threats against Vicksburg and northern Mississippi were more ominous. But Bragg soon learned that the situation had shifted in his favor.

Early in June, Halleck divided his horde, assigning one army to secure West Tennessee, another to move south toward Tupelo and a third, under Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, to march across northern Alabama, link up with Federals already there and capture Chattanooga. The enemy’s dispersal provided Bragg with an opportunity to retake Corinth, but the condition of his army—demoralized by its failure at Shiloh in April and subsequent abandonment of Corinth—prevented him from doing so immediately. Bragg faced escalating desertions, food shortages, inadequate transportation and, in his opinion, a lack of competent junior officers.

In the interim, Bragg focused on securing the two geographical locations he considered strategically critical to the Confederacy: Vicksburg and Chattanooga. Davis had ordered Bragg to take temporary command of Department No. 1 on June 14. But since Bragg was unable to leave Tupelo, Davis notified him on June 19 to send Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn. Charged with holding Vicksburg, Van Dorn took over an area reduced in size and renamed the Department of Southern Mississippi and East Louisiana. Bragg authorized Van Dorn to use 8,500 of Bragg’s troops in northwestern Mississippi. Rather than weaken his force at Tupelo or leave Vicksburg in danger, Bragg chose to abandon strategically insignificant northwestern Mississippi. Securing Chattanooga proved to be more elusive.

Beauregard had ignored Smith’s requests for assistance. And when the War Department ordered him to reinforce Smith, Beauregard refused, claiming such a move “would be fatal,” since he expected to face superior forces any day. On June 20, the day Bragg succeeded Beauregard for good, Smith notified him that he had abandoned the Cumberland Gap and that without two additional brigades he could not guarantee the safety of the railroad that provided the shortest route between Richmond and the Western Confederacy. Anxious to strike at Corinth, Bragg initially did nothing. Two days later he urged the War Department to send reinforcements from the Atlantic Coast to Smith. Secretary of War George Randolph responded that troops had already been sent to Chattanooga from the coast. If more were needed, he urged Bragg to send them. Again Bragg declined, still hoping help would materialize from elsewhere. But this exchange with Randolph got Bragg thinking about his responsibilities.

So Bragg requested clarification of the geographical limits of his command, even asking if he was in charge of “the Western Department or Department No. 2.” Six days would pass before Randolph telegraphed an inaccurate response. That misleading message, coupled with intervening events, would be the undoing of Bragg’s offensive against Corinth.

On June 27, having heard nothing more from Randolph or Smith and confident Vicksburg and Chattanooga were secure, Bragg issued a proclamation announcing his formal assumption of permanent command of Department No. 2. It concluded with a promise: “A few more days of needful preparation and organization and I shall give your banners to the breeze.” His advance on Corinth was imminent.

At this point a telegram arrived from Smith: “Buell is reported crossing the river at Decatur and daily sending a regiment by rail toward Chattanooga. I have no force to repel such an attack.” Believing that East Tennessee was his responsibility, Bragg had already made the necessary preparations. Maj. Gen. John P. McCown left immediately with two brigades (3,000 men) of the Army of the West. Bragg also decided to forgo his advance on Corinth until Chattanooga was secure.

While awaiting an update from Smith, Bragg labored to improve his forces at Tupelo. The departure of McCown allowed Maj. Gen. Sterling Price to assume command of the Army of the West. The promotion convinced the Missourian to remain with Bragg, and Price boosted his troops’ morale by promising to lead them back to Missouri by way of Kentucky. Believing Leonidas Polk was a better bishop than general, Bragg elevated him to second in command of the department so Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee could take charge of the Army of the Mississippi. Hardee’s prior experience made him the most qualified to train troops. Alive to the strategic implications of railroads, Bragg pushed for completing the railroad from Meridian, Miss., to Selma, Ala.

On June 29, Randolph notified Bragg: “Your department is extended so as to embrace that part of Louisiana east of the Mississippi, the entire States of Mississippi and Alabama, and that portion of Georgia and Florida west of the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers.” While notifying Bragg of his responsibility for Vicksburg, Randolph neglected to mention either Tennessee or the name of Bragg’s department. As a result, Bragg believed that he was responsible for the whole of Tennessee. Randolph’s failure to inform him that East Tennessee remained an independent department left Bragg’s destiny in Smith’s hands.

During the first week of July, while Bragg was still readying the troops at Tupelo for an offensive against Corinth, Buell continued to move. But to what end? Inaccurate reports led Bragg and Smith to conclude that Buell, possibly in response to Rebel victory during the Seven Days’ Battles in Virginia, was withdrawing to Nashville and even beyond. Both men seized upon this news because it freed them to pursue their own plans: Bragg could attack Corinth and Smith could move against Cumberland Gap.

July 10 put an end to these plans. Buell was approaching Chattanooga with nearly 30,000 troops, Smith told Bragg. “I see by the Northern papers that three divisions of Grant’s army are to operate against East Tennessee in connection with Buell’s corps,” Smith wrote Davis three days later. This “overwhelming force” couldn’t be resisted “except by Bragg’s cooperation.” Smith didn’t want reinforcements; he wanted Bragg to invade Middle Tennessee, thereby relieving him of the responsibility of defending Chattanooga. Moreover, Smith continued, “the disorders in [Kentucky] are extremely propitious for [John Hunt Morgan’s] operations.” If the Kentuckians enthusiastically welcomed raiding Confederate cavalry, then, Smith surmised, they would welcome his entire command. Smith was determined to invade Kentucky.

Ignoring Buell, Smith on July 17 began shifting troops from Chattanooga toward Cumberland Gap. He knew full well, however, that to justify entering Kentucky, Chattanooga must be either secure or someone else’s responsibility. Two days later he telegraphed Bragg, urging him to enter Middle Tennessee and promising to cooperate. This gave Bragg pause. Maybe East Tennessee wasn’t part of his department, but Smith’s pleas for help sounded ominous. If Chattanooga was his responsibility, he had to move quickly. On July 20, Bragg sought clarification from Smith:

I am left in doubt…whether yours is a separate command, or still, as formerly a part of General [Albert Sidney] Johnston’s old department and hence embraced within my command. Can you enlighten me by copies of any orders or instructions you may have? My only desire is to know the precise limits of my responsibilities, not to interfere in the least with your operations and command, as you must know best when and how to act, and have my fullest confidence.

Because he deemed East Tennessee strategically more important than northern Alabama and Mississippi, Bragg did not wait for confirmation about the limits of his department. He started moving the Army of the Mississippi to Chattanooga immediately. By having infantry from the Mobile garrison precede him—which he replaced with the last of his army—reinforcements reached Chattanooga by July 27. This was not how Bragg wanted to secure the city, and Kentucky never entered his thoughts. Though most historians argue that Bragg had decided to invade Kentucky before leaving Tupelo, his July 20 letter to Smith states otherwise. Moreover, the movements of Maj. Gen. Jones Withers’ Reserve Corps between Tupelo and Corinth between June 27 and July 21 indicate that the object of Bragg’s offensive was much closer than the Bluegrass State.

Had Bragg learned the boundaries of his department before July 27, he would have halted Buell’s advance by striking Corinth and pressing on toward Nashville. By this time the odds had shifted in his favor in northern Mississippi, plus the Federals were dispersed in relatively isolated detachments. But by the 27th, the die had been cast.

Bragg arrived in Chattanooga on July 30 and met with Smith the next day. On August 1, Bragg outlined his plan to the War Department. It would take at least 10 days before his army, awaiting the arrival of its artillery and wagon train from Mississippi, could take the offensive. Rather than do nothing, Smith’s troops, augmented by two of Bragg’s brigades, would strike Cumberland Gap. If successful, it would free many of Smith’s men to join Bragg’s offensive against Buell. They would help offset any advantage Buell gained because of Bragg’s delay. And if Buell was reinforced from Corinth, Van Dorn could join with Price’s Army of the West for an offensive against West Tennessee. Though Bragg noted the reports that Kentuckians “wanted but arms and support” to join the Confederacy, he made no mention of entering the Bluegrass State.

On August 9, Smith informed Bragg that the Union garrison at Cumberland Gap purportedly had a month’s supply of rations. As that was more time than he believed Bragg would approve, rather than joining Bragg to assault Buell, Smith requested permission to move to Lexington, Ky., promising “other most brilliant results” besides isolating Cumberland Gap.

Bragg considered his options. Buell had undoubtedly concentrated his men in the fortifications surrounding Nashville. Even with his force augmented with Smith’s troops, an attack would be too costly, especially if reinforcements had reached Buell from Corinth. Having no immediate need for Smith’s troops, Bragg authorized him to enter Kentucky, urging him to coordinate his movement with Confederate Brig. Gen. Humphrey Marshall’s force, entering that state from Virginia, and not to wander far beyond the state line before Bragg confronted Buell.

Unwilling to assault Nashville, Bragg pondered possibilities beyond Middle Tennessee. Maybe by maneuver, rather than fighting, the Confederates could regain territory they had lost the previous six months. Threatening Buell would not only protect Smith but enable Van Dorn and Price to enter West Tennessee. His decision made, on August 24 Bragg approved Smith’s renewed request to move on Lexington. Confederate success depended on coordination, cooperation and communications.

And there’s the rub. The standard argument is that because Smith, whom Bragg outranked, commanded a department, he was subject to Bragg’s orders only when they were together. With no control over Smith’s movements and rapid communication with Van Dorn and Price about to end, Bragg’s strategy was thus doomed from the start. While hindsight supports this conclusion, it ignores two critical points. First, before August 24, every piece of correspondence between Bragg and Smith and every action Smith took demonstrates that he explicitly followed Bragg’s orders. Second, Bragg had no reason to believe that Smith, or anyone else, would fail to follow his orders.

But discord crippled the high command of the Army of the Mississippi. Hard feelings between Bragg and Polk predated Shiloh, and after Bragg replaced Beauregard, he wanted to promote officers he deemed more competent. For weeks Bragg had urged President Davis to relieve four major generals—Polk, Benjamin Cheatham, Samuel Jones and John P. McCown. For political and legal reasons Davis declined, leaving Bragg to deal with the fallout from his failed request. He had already transferred McCown to Smith, who left him behind in command at Knoxville. Bragg would get rid of Jones by leaving him behind in command at Chattanooga. That left Polk, second in command of the department, and Cheatham, who commanded a division. Hardee, the sole remaining major general, commanded the army. On August 15, Bragg made a fateful decision. Deeming it necessary to divide the army into two wings for the coming campaign, he resumed immediate command of the army himself and demoted both Polk and Hardee to wing commanders, a move that alienated the latter for good. To have done otherwise, however, would have resulted in Cheatham and a brigadier general in charge of the wings.

Ironically, Bragg learned two days later that Simon Bolivar Buckner, who had surrendered Fort Donelson in February, had been exchanged, promoted to major general and ordered to Tennessee. Had he known that earlier, Bragg might have given Buckner and Cheatham a wing instead of a division, thus obviating the demotions of Polk and Hardee. Such an arrangement would also have enabled Bragg to leave Polk behind to oversee the department, particularly the operations of Van Dorn and Price, whom Bragg repeatedly urged to unite and enter West Tennessee. Even if such a move had failed to halt reinforcements departing to join Buell, the combined Rebel force could overwhelm what remained of the enemy in that region. Unfortunately, Bragg never informed the War Department about his instructions to Van Dorn and Price. So Van Dorn didn’t cooperate with Price until September 11, when a hesitant Davis honored his request to assume command of Price. On September 18, Price, at Iuka, Miss., learned he now reported to Van Dorn, who ordered him to join him at Rienzi for an attack on Corinth. Before he could do so, he was defeated the following day. As that defeat was followed by one at Corinth, had Bragg chosen to leave Polk behind in charge of the department, the bishop could hardly have made matters worse. He would have done less damage in Mississippi than he did in Kentucky.

Though President Davis, Smith and Tennessee Governor Isham Harris united in urging Bragg to defeat Buell before entering Kentucky, it is impossible to know what Bragg intended to do when he departed Chattanooga on August 28. The popular notion is that an indecisive Bragg simply hoped to maneuver Buell out of Middle Tennessee without a major engagement. When Bragg reached Sparta on September 4, he was informed that Buell was in Nashville, Smith was in no danger and forage was scarce along the route to Lexington via Albany. Unwilling to attack Nashville, Bragg found himself with three good reasons to cut Buell’s supply line to Louisville.

Three days later Bragg, still at Sparta awaiting the arrival of the rear of his column, received erroneous intelligence that Buell was abandoning Nashville. This news spurred Bragg northward. He blocked Buell’s direct route to Louisville by capturing Munfordville on September 17. Unable to lure Buell into attacking and forced to move because of a supply shortage, Bragg pushed on to Bardstown and ordered Smith to concentrate his troops at Shelbyville. Expecting the two armies to be positioned for a joint advance on Louisville, Bragg soon learned that Smith’s men remained scattered across eastern Kentucky. Too weak alone to do otherwise, Bragg did not contest Buell’s march to Louisville. To decisively defeat him, the Confederates needed to unite all their forces. So on September 28 Bragg turned the army over to Polk and headed to Lexington, seeking Smith and answers.

The only Confederate multi-army offensive of the war was in shambles, with failures all over the map. Smith’s decision to ignore Bragg’s orders had prevented a concentration in Kentucky against Buell. Smith and Marshall had allowed the garrison at Cumberland Gap to escape. Van Dorn’s expedition into Louisiana under Kentuckian Brig. Gen. John C. Breckinridge kept reinforcements and the former U.S. vice president from joining Bragg. And in Mississippi, Van Dorn and Price failed to invade West Tennessee after allowing reinforcements from Corinth to reach Buell. Meanwhile Kentucky provided few recruits for the Army of the Mississippi, and Bragg was still plagued with faulty intelligence.

With Buell reportedly moving on Frankfort, Ky., Bragg, who was at Lexington on October 2, planned a Napoleonic concentration. Smith would engage Buell in front while Polk struck his right flank near that town. Learning that Buell was actually moving on Bardstown, Polk disobeyed Bragg’s orders and marched east instead of north. Bragg then ordered Polk, Smith, Marshall, Breckinridge (from Knoxville) and Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson (from the Cumberland Gap) to concentrate at Harrodsburg. Two days later Bragg telegraphed Polk: “Keep the men in heart by assuring them it is not a retreat, but a concentration for a fight. We can and must defeat them.”

At midday on the 7th, on being informed that Buell was moving from Louisville along several routes, Bragg determined to destroy the Federals in detail beginning with those harassing Polk near Perryville. Poor intelligence-gathering by Smith coupled with subordinates issuing conflicting orders resulted in Bragg’s fighting the Battle of Perryville with only three divisions. Unaware he was outnumbered 3-to-1, Bragg attacked on October 8 and, thanks to some bizarre circumstances, won a tactical victory by nightfall.

Although both sides expected the fighting to resume at dawn, Bragg—who was now aware of the odds—ordered a withdrawal toward Harrodsburg to prevent Buell from cutting off Smith. But this provided Buell with the opportunity to strike directly for Bragg’s supply base at Bryantsville. Before Smith reached Harrodsburg, Bragg already had Polk marching to Bryantsville. Thanks to Buell’s slow advance, Bragg finally succeeded in concentrating most of the Confederates in Kentucky. But Smith had neglected to transport sufficient foodstuffs from Lexington to Bryantsville, an area offering little sustenance. Bragg thus had but two choices: advance or retreat.

Reinforcements had not arrived, and there were rumors of Van Dorn’s defeat at Corinth. Meanwhile the expected influx of Kentuckians eager to fill Bragg’s ranks proved chimerical. When asked how to measure a general’s greatness in the Napoleonic Wars, the Duke of Wellington answered, “To know when to retreat and to dare to do it.” Luckily for the South, Bragg had the courage to order a retreat.

But had the campaign been a failure? The Rebels had lived off Federal territory, won the most lopsided victory of the war at Richmond, Ky., captured the garrison at Munfordville, retaken Cumberland Gap, won a tactical victory at Perryville and gained thousands of recruits. Their orderly retreat made it appear to both sides and to Europeans that they could almost come and go as they pleased. Union troops had been cleared from northern Alabama, Middle Tennessee below Nashville and East Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s operations against Vicksburg were delayed because of Van Dorn and Price and by having to reinforce Buell. Port Hudson, La., had been seized, providing control of a stretch of the Mississippi as well as the Red River. Chattanooga was retained for another year. Can it be denied that Bragg’s strategy prolonged the war?

Unlike Beauregard, Bragg recognized the importance of Vicksburg and Chattanooga and weakened his own command to secure them—even when they were not his responsibility. Bragg demonstrated a better command of grand strategy than any other Confederate general during the war, with the possible exception of Robert E. Lee. After leaving Kentucky, a Tennessee woman wrote: “When the History of this war is impartially written, it is my deliberate opinion, that to Bragg will be awarded the praise of having done more with his men and means, than any other Gen. of the War, with equal resources.” Will the “disgusting” Bragg ever receive a fair hearing? Not before Southerners realize Lee was a mere mortal, one who failed Wellington’s test of greatness by risking the destruction of his army by remaining at Sharpsburg on September 18, 1862.

Nevins-Freeman Award winner Lawrence Lee Hewitt is the author or editor of more than a dozen books, including Port Hudson, Confederate Bastion on the Mississippi. This article was originally published in the February 2014 issue of Civil War Times.