From Dred Scott to anchor babies, ‘Born in the USA’ has caused hot debate

THE CIVIL WAR brought freedom to four million enslaved people. However, in January 1866, the meaning of that freedom under the law remained nebulous. The 13th Amendment, which states had ratified in December 1865, outlawed slavery. In 1857, however, the U.S. Supreme Court had in Scott v. Sandford denied citizenship to African-Americans, even those born in the United States. To Senator Lyman Trumbull (R-Illinois), the status quo—freedom without citizenship—smacked of continued involuntary servitude. The formerly enslaved born in America deserved birthright citizenship, the same as any white American enjoyed, Trumbull reasoned, and he vowed to make that reasoning a reality.

On January 5, 1866, Trumbull introduced S-61, a bill to grant citizenship to all freed slaves born in the United States. He expected Congress to pass this bill, formally known as “An Act to protect all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and furnish the Means of their Vindication,” and President Andrew Johnson to sign it into law.

However, citizenship proved a more divisive issue than Trumbull had envisioned, and in a controversy with echoes into the present, Congress spent months heatedly debating who deserves to be an American.

Initially, the concept of American citizenship was unsettled. Foreign-born immigrants became citizens by naturalization, a process the first Congress codified in 1790 that was limited to white persons and activated only after a five-year wait. Immigrants’ children born in

the United States, however, enjoyed citizenship by virtue of jus soli, “right of the soil,” regardless of parental nationality. Jus soli, also called birthright citizenship, had originated in England and had emigrated to the colonies with the first settlers from that nation. Still, the issue was not clear-cut, since neither the Constitution nor any statute expressly recognized or defined birthright citizenship. Jus soli was assumed to be the law, its theoretical and practical contours vague.

The United States was a nation of immigrants, and in the early 1800s its borders were open, with entry unrestricted. America needed hands to farm, backs to toil in factories, and pioneers to settle the West. By 1860, the population was 31.4 million, including 4.1 million foreign-born residents. Since Day One, European immigrants had come mostly by choice—except those Britain had transported as punishment. Most Americans of African descent had had no choice, arriving as they or their antecedents had in shackles as chattel. By 1860, the slave population of the United States of America had reached 3.9 million, mostly native-born.

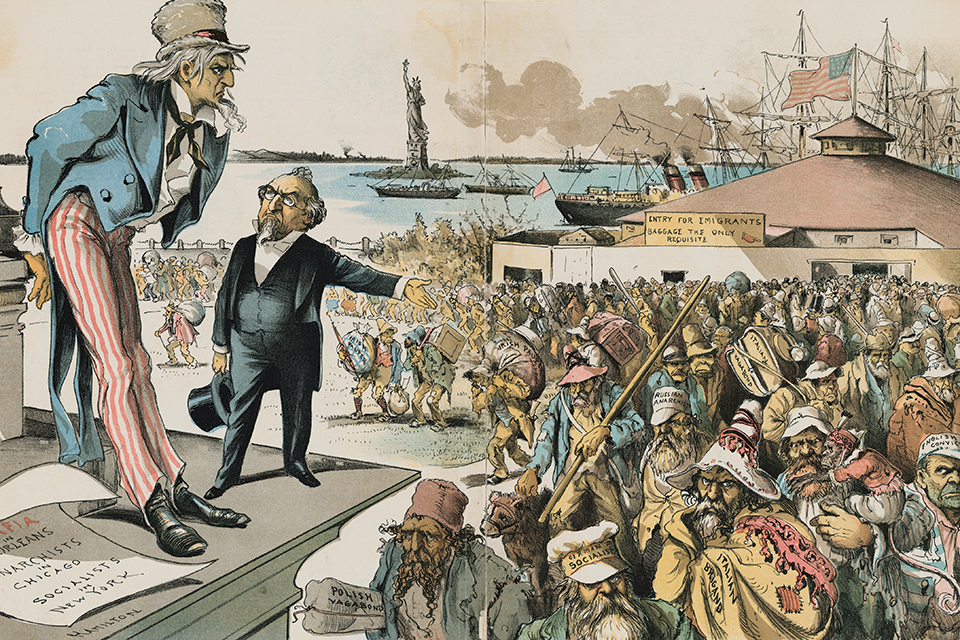

Between 1820 and 1860 tentative streams from Ireland and other European countries began what would become an immigrant tide, causing xenophobia among so-called nativists to surge. These descendants of immigrants formed the anti-immigrant American Party, or Know-Nothings—if queried about the party, members were instructed to say they knew nothing—whose 1856 platform proclaimed that “Americans must rule America.” That year, the party’s presidential candidate, former chief executive Millard Fillmore, won 21.5 percent of the popular vote. Xenophobia was not universal. As of 1861, five states—Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Oregon, and Wisconsin—allowed non-citizens to vote. In 1862, the Homestead Act, implemented to settle portions of the West, allowed foreigners stating their intent to become citizens to take possession of publicly offered land.

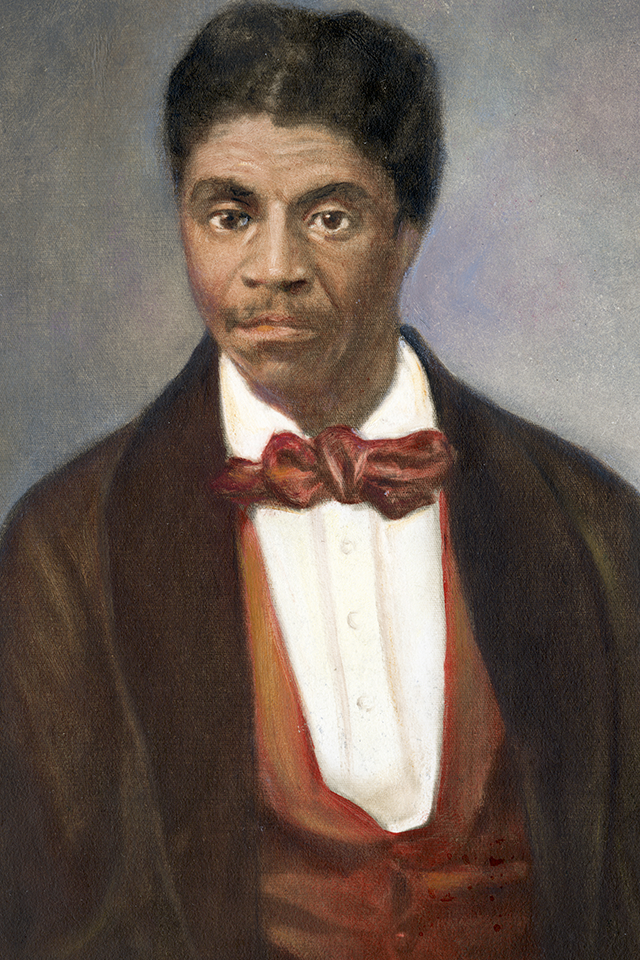

The issue of birthright citizenship had reached the Supreme Court in 1857. Dred Scott, a slave born in Virginia, had sued his owner for his freedom in federal court after the planter brought Scott to a non-slave state. The owner, a U.S. Army surgeon, had taken Scott for several

years to the free state of Illinois and the free territory of Wisconsin before returning the slave and his family to the South. Scott needed to establish jurisdiction before the courts would consider his case; he invoked diversity jurisdiction, which allows a citizen of one state to sue a citizen of another in federal court. Citizenship seemed to be a given for the American-born Scott, but the Supreme Court disagreed, closing the courthouse door by holding that African-Americans were not citizens. Writing for the seven-justice majority, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney called blacks “beings of an inferior order” with “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Advocates of slavery rejoiced. Foes mourned. Enmity between North and South deepened.

During the Civil War, immigrants and African-Americans rallied to the flag. More than 500,000 foreign-born men—some naturalized, some non-citizens—and nearly 200,000 African-Americans fought for the Union. After the war, the 39th Congress faced the task of reunifying the country and eradicating bondage and its vestiges. On December 6, 1865, Georgia became the 27th state to ratify the 13th Amendment, and slavery was outlawed. The next step was establishing citizenship for the formerly enslaved. Importation of slaves had ended in 1807; most freedmen of the day had been born in the United States. The Scott decision flatly denied them citizenship. Nullifying that ruling would be politically astute for the Republicans controlling Congress. Citizenship begat suffrage and GOP leaders expected that African-Americans would embrace the political party that had freed them.

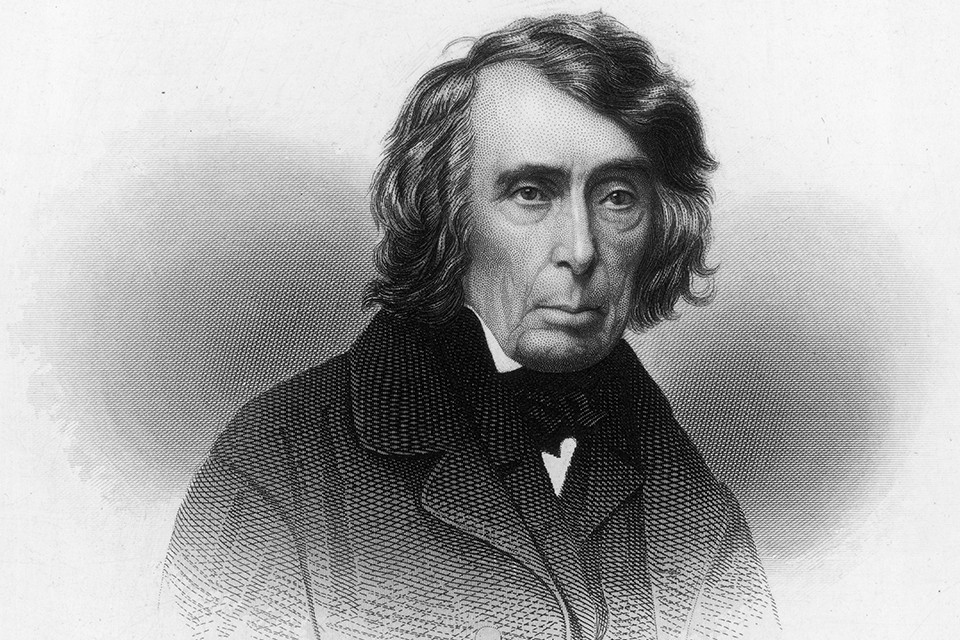

Trumbull, 52, was point man on the citizenship drive. A moderate elected to the Senate in 1854, he had chaired the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee since 1861.

The Illinois Republican was well-respected but aloof, lacking “the warmth of temperament calculated to win personal friendship,” a contemporary noted. The slim, 5’10’ Trumbull bore “a cast of countenance which marks the man of thought” and was a “clear and cogent reasoner” but not “gifted with personal ‘magnetism.’”

Trumbull may have seen citizenship for freed slaves as a matter of fairness, but he was a white man of his age. “Among the strongest anti-slavery champions in the West” and known in his lawyering days for representing slaves suing for freedom, he had as a senator drafted the 13th Amendment. Even so, in an 1858 speech, he had declared, “I want to have nothing to do either with the free negro or the slave negro.”

Introduced on January 5, 1866, Trumbull’s bill, now known as the Civil Rights Act of 1866, initially sought to make birthright citizens of “persons of African descent born in the United States.” Trumbull soon realized his bill’s language was too restrictive, implying as it did that only African-Americans qualified for jus soli. On January 30, 1866, he submitted a rewrite to cover “(a)ll persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign Power.”

Trumbull’s revised bill codified the long-held belief that children born in the United States were American citizens. “As a matter of law, does anyone deny here or anywhere that the native born is a citizen, and a citizen by virtue of his birth alone?” asked Senator Lot M. Morrill (R-Maine). Officially recognizing that principle, however, had wider implications, and officials worried about the bill’s reach.

Would enactment of the bill make citizens of “the children of Chinese and Gypsies born in this country?” asked Senator Edgar Cowan (R-Pennsylvania). “Undoubtedly,” Trumbull replied. Cowan angrily predicted that “the day may not be very far distant when California, instead of belonging to the Indo-European race, may belong to the Mongolian…” The very idea of granting non-whites citizenship outraged Senator Garrett Davis, a Unionist from Kentucky. Defining the American nation as a “Government and a political organization of white people,” Davis asserted that when “a negro or Chinaman is attempted to be obtruded into it, the sufficient cause to repel him is that he is a negro or Chinaman.” Senator Peter G. Van Winkle, a West Virginia Unionist, feared immigrants “whose mixture with our race…could only tend to the deterioration of the mass.” Van Winkle worried that the bill’s language was broad enough to cover “a future immigration to this country of which we have no conception.”

Representative James F. Wilson (R-Iowa) insisted the bill’s reach was not unlimited. According to Wilson, that reach excluded “children born on our soil to temporary sojourners,” a remote issue, since owing to travel cost and time, most who came to America came to stay.

The outcome was never in doubt. Republicans enjoyed a healthy majority in both houses, and the former Confederate states had not yet regained representation in Congress. On February 2, 1866, the Senate passed the bill 33-12. On March 13, 1866, the House approved 111-38. The Civil Rights Bill of 1866 went to President Johnson for his signature.

Trumbull, who had met with the president while the bill was pending, believed he had Johnson’s support. He felt betrayed on March 27, 1866, when the president vetoed the bill. Johnson claimed that since a European immigrant had to undergo a five-year wait to seek citizenship but a former slave would not, the bill discriminated “against large numbers of intelligent, worthy, and patriotic foreigners, and in

favor of the Negro.” Reaction to Johnson’s veto was mixed. The Nation attacked its logic as “that of a stump speech, and its law would hardly pass current in a college moot court.” The New York Times praised Johnson for rejecting the bill’s favoritism for the “black freedman” over the “white immigrant.”

Counterattacking on April 6, 1866, the Senate overrode Johnson’s veto 33-15. The vote drew applause in galleries that included “some hundreds of men of color…whose dusky but earnest faces were bent upon the fate of the bill.” Three days later, the House overrode the veto 122-41, with the ensuing applause “especially strong from the ‘colored galleries.’”

Birthright citizenship was now the law, but supporters were uneasy. If one Congress could adopt jus soli by legislation, a later Congress could reverse that action just as easily. A constitutional amendment, Republican leaders felt, would give greater permanence. They tacked citizenship onto the 14th Amendment, pending in the Senate.

On May 30, 1866, Senator Jacob M. Howard (R-Michigan) added language to the amendment granting citizenship to “all persons born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” This provision was, Howard said, “simply declaratory of what I regard as the law of the land already.” Making that change, he said, would remove “all doubt as to what persons are or are not citizens of the United States,” an issue Howard called “a great desideratum in the jurisprudence and legislation of this country.” The “subject to” clause, he explained, would exclude children born to foreign ambassadors in America and those born to members of Indian tribes Congress treated as sovereign. Neither foreign diplomats nor these Native American tribes were considered subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. Native Americans had to wait until 1924 for citizenship.

Pennsylvania Senator Cowan, jus soli’s most vocal foe, trotted out the bogeymen of the day: Gypsies and the Chinese. The Republican said he opposed citizenship for Gypsies, who, he said, “wander in gangs in my State…(and) followno ostensible pursuit for a livelihood.” This was too much for Senator John Conness (R-California), who knew firsthand about immigration and bigotry. Born in Ireland in 1821, he had come to America in 1836 and had lived through the Know-Nothing era. “I have heard more about Gypsies within the last two or three months than I have heard before in my life,” Conness quipped, accusing Cowan of conjuring imaginary Gypsy hordes “so that hereafter the negro alone shall not claim our entire attention.”

Cowan, who claimed to be “as liberal as anybody toward the rights of all people,” saved his strongest acid for the Chinese. “[I]s it proposed that the people of California are to remain quiescent while they are overrun by a flood of immigration of the Mongol race?” he asked. “Are they to be immigrated out of house and home by Chinese?” Conness mocked Cowan’s argument. “It may be very good capital in an electioneering campaign to declaim against the Chinese,” the California senator told his colleague, adding that Cowan should “give himself no further trouble on account of the Chinese in California.”

Cowan had a loud voice but few votes. On June 8, 1866, the Senate passed the 14th Amendment 33-11, well exceeding the required two-thirds majority. On June 13, the House approved 120-32. The president’s signature was not needed to amend the Constitution, and the 14th Amendment went to the states for ratification. Ratification required approval by three quarters of the states. The amendment’s contentiousness rendered the process rough. Besides recognizing birthright citizenship, the instrument guaranteed due process and equal protection for all, meanwhile permanently barring certain former Confederate officials from federal office. The 11 former Confederate states, still not back in Congress, did count for ratification purposes, meaning for the amendment to become law, 28 of the 37 states had to approve. When the former rebel states balked, Congress threatened to withhold readmission to Congress. On July 9, 1868, South Carolina, the first state to secede from the Union, became the 28th to ratify the amendment.

However, there was a bump. After ratifying the amendment, New Jersey and Ohio had rescinded their ratifications in formal votes by their legislatures. No one was sure what rescission meant, except to rattle the amendment’s backers. Ratification by Alabama and Georgia removed any doubt, bringing the total of state ratifications again to 28, and on July 28, 1868, Secretary of State William H. Seward certified the 14th Amendment as adopted.

It had taken Lyman Trumbull two years, but he had succeeded in his quest for birthright citizenship. Trumbull’s conscience, which had told him that people deserved certain basic rights, was his undoing. Seeing radical Republicans’ impeachment of Andrew Johnson as a partisan vendetta, in May 1868 he attacked his own party’s “intemperate zealots” for seeking Johnson’s removal. When impeachment came to a vote in the Senate, Trumbull voted to acquit, effectively ending his political career. He retired from the Senate when his term ended in 1873.

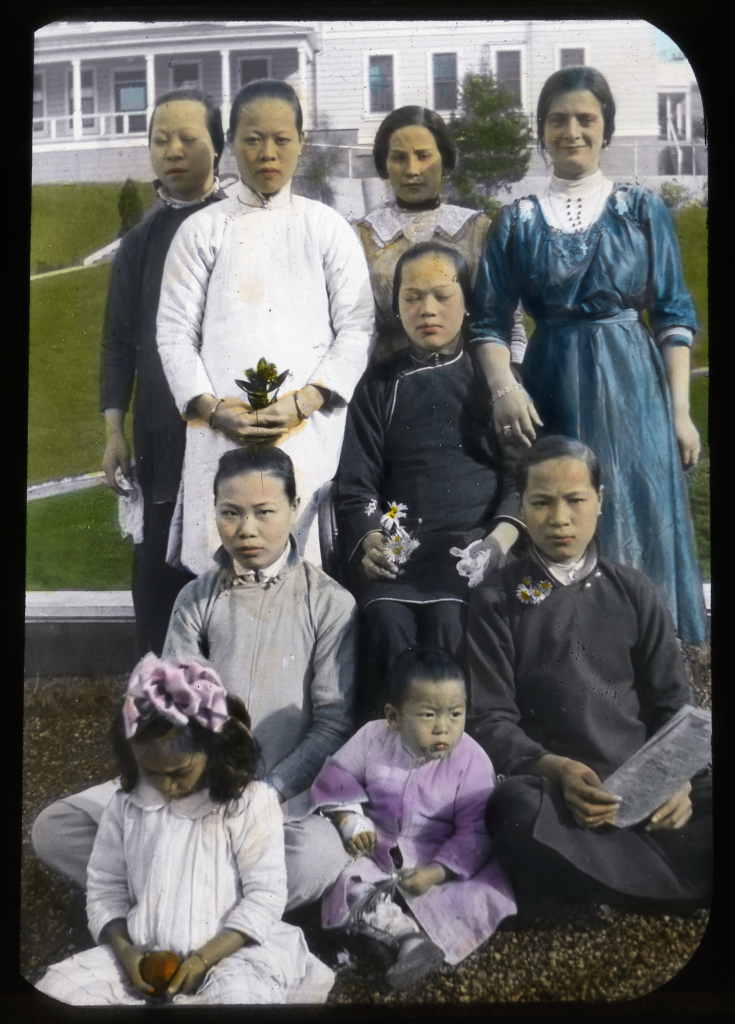

Over the next two decades, immigration policy began to acquire its modern form by means of a rolling drumbeat of restrictions for entry. In 1875, Congress barred entry by prostitutes and foreign convicts, though providing no mechanism to determine who was a prostitute or convict. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act barred laborers from that country and denied naturalization to Chinese immigrants

already living in the United States. The same year, Congress prohibited entry by any “lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.” In 1891, Congress excluded “persons suffering from a loathsome or a dangerous contagious disease” and polygamists. Imposition of these restrictions created a category for individuals coming to America in violation of these restrictions. Today they are called illegal aliens or undocumented immigrants, phrases unknown to the 39th Congress because in 1866 anyone could enter, and not until the 20th century did Congress begin setting country by country quotas for admission. Deportation also entered the picture, with Congress in 1891 ordering that anyone caught trying to enter illegally “be immediately sent back on the vessel Co. by which they were brought in.” Any forbidden immigrant found to have sneaked in was to be “returned as by law provided.”

Executive agencies imposed particular limits on birthright citizenship. In 1884, Ludwig Hausding, raised in Germany, sought an American passport, claiming to be a U.S. citizen because he had been born here. On January 15, 1885, however, Secretary of State Frederick T. Frelinghuysen refused to issue the passport, finding that Ludwig was not a citizen because his German parents were not immigrants but only temporary visitors when their son was born. Later that year, the State Department came to the same conclusion regarding Richard Greisser, whose German father and Swiss mother had been visiting the United States at the time of his birth.

Customs officials had their own restrictions. In August 1895, California native Wong Kim Ark, 22, visited relatives in China and returned to San Francisco. Customs collector John H. Wise refused to let Wong land. Born in San Francisco in 1873, Wong was as American as Wise, but the customs man, a self-proclaimed “zealous opponent of Chinese immigration,” could not see beyond Wong’s “race, language, color, and dress.” Wong was imprisoned aboard ship in San Francisco Bay when attorney Thomas D. Riordan, known for his work on behalf of Chinese-Americans, came to his aid. Wong went to court. His case set the contours of birthright citizenship when the U.S. Supreme Court sided with him in a landmark 1898 decision. Writing on behalf of the six-member majority, Justice Horace Gray described Wong’s ancestry as irrelevant and found him to be as American as the Fourth of July. Gray wrote that except for the children of foreign ambassadors and Native Americans, “[e]very person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, becomes at once a citizen of the United States, and needs no naturalization.”

To hold otherwise, Gray noted, “would be to deny citizenship to thousands of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, German, or other European parentage, who have always been considered and treated as citizens of the United States.” Two justices disagreed. Dissenting Chief Justice Melville Fuller saw peril in jus soli for parents in the country unlawfully. The parents could be deported, he wrote, but as citizens, their children could stay. He decried as “cruel and unusual punishments” any move to “tear up parental relations by the roots.”

Wong Kim Ark, still in effect today, seemed to settle the issue of birthright citizenship. However, the decision may have left open the question of jus soli for the temporary visitors’ issue and for children of those in the country unlawfully. The Supreme Court did not explicitly address either scenario because Wong’s parents were neither temporary visitors nor illegal aliens. They had emigrated before 1882 to settle and to run a business.

Birthright citizenship remains a flash point, and full resolution of the issue’s disputatious aspects may require another Supreme Court ruling, perhaps equal in significance to the Court’s 1857 citizenship ruling. “Stay tuned,” legal scholar James C. Ho, now a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals, wrote in a 2006 law journal article. “Dred Scott II could be coming soon to a federal court near you.”

_____

Still Making Headlines

The American argument over birthright citizenship continues, with unexpected twists and a profound constant—the nation is still one of immigrants. The 2010 census counted some 40 million residents—13 percent of the population—were born elsewhere. Rules on lawful entry and stay are strict, but some estimates have more than 20 million people living illegally in the United States.

Jus soli reverberates far beyond anything members of the 39th Congress could have imagined. In 1866, the country had no curbs on entry; today, birthright citizenship can legitimize the status of immigrants who entered illegally. In 2017, nearly 150,000 people became permanent residents based on sponsorship by their children, the Department of Homeland Security states.

When unauthorized immigrants have a child in the United States, that child is a citizen. Raising a child who is a citizen enhances parents’ chances of gaining permanent residence. Upon turning 21, that child can sponsor his or her parents for lawful permanent residence. These offspring often are called “anchor babies,” a term immigration advocates view as pejorative. The Center for Immigration Studies says more than 300,000 American children per year are born to unauthorized immigrants. Jus soli has spawned birth tourism, a social phenomenon and a business. Affluent foreigners on tourist visas flock to bear children on American soil, obtaining a foothold on residence—highlighted recently by federal indictments arising from 2015 raids on Los Angeles-area operations alleged to engage in visa fraud, wire fraud, and identity theft. Chinese women pay as much as $80,000 to companies that handle logistics, providing “apartments in complexes boasting resort-style opulence and amenities and outings to upscale eateries, Disneyland and a shooting range,” the Wall Street Journal reported in 2015. Miami-based birth brokers charge comparably to provide such services to Russian and Brazilian women. “Crowds of pregnant girls come here and then take away crowds of little Americans,” a Russian mother who gave birth in Miami told the London Times in 2018. Customers pay separately, usually in cash, for medical care, often obtaining U.S. passports for their babies before returning home. No law regulates such expeditions, as long as pregnant travelers do not lie about their visits’ purpose. The Center for Immigration Studies estimates that birth tourists have more than 30,000 American babies per year.

Since the 14th Amendment enshrines jus soli, only a new reading by the U.S. Supreme Court or a constitutional amendment can change that principle. A 2015 CNN/ORC poll showed that half of Americans favor retaining birthright citizenship, even for children of unauthorized immigrants; 49 percent want the law changed.

Congress repeatedly has weighed and found wanting bills to eliminate jus soli for visitors’ children or unauthorized immigrants’ offspring by requiring that at least one parent be a citizen or a legal permanent resident. The U.S. Justice Department insists that only a constitutional amendment—a process that requires a two-thirds vote by both houses of Congress and ratification by three-quarters of the 50 states—can change birthright citizenship. Great Britain, originator of the American principle of jus soli, eliminated unconditional birthright citizenship in 1981, limiting jus soli to children with at least one parent who is a British citizen or a lawful permanent resident. —Joseph Connor